Orthonormality

In linear algebra, two vectors in an inner product space are orthonormal if they are orthogonal and unit vectors. A set of vectors form an orthonormal set if all vectors in the set are mutually orthogonal and all of unit length. An orthonormal set which forms a basis is called an orthonormal basis.

Intuitive overview

The construction of orthogonality of vectors is motivated by a desire to extend the intuitive notion of perpendicular vectors to higher-dimensional spaces. In the Cartesian plane, two vectors are said to be perpendicular if the angle between them is 90° (i.e. if they form a right angle). This definition can be formalized in Cartesian space by defining the dot product and specifying that two vectors in the plane are orthogonal if their dot product is zero.

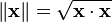

Similarly, the construction of the norm of a vector is motivated by a desire to extend the intuitive notion of the length of a vector to higher-dimensional spaces. In Cartesian space, the norm of a vector is the square root of the vector dotted with itself. That is,

Many important results in linear algebra deal with collections of two or more orthogonal vectors. But often, it is easier to deal with vectors of unit length. That is, it often simplifies things to only consider vectors whose norm equals 1. The notion of restricting orthogonal pairs of vectors to only those of unit length is important enough to be given a special name. Two vectors which are orthogonal and of length 1 are said to be orthonormal.

Simple example

What does a pair of orthonormal vectors in 2-D Euclidean space look like?

Let u = (x1, y1) and v = (x2, y2). Consider the restrictions on x1, x2, y1, y2 required to make u and v form an orthonormal pair.

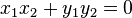

- From the orthogonality restriction, u • v = 0.

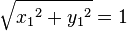

- From the unit length restriction on u, ||u|| = 1.

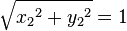

- From the unit length restriction on v, ||v|| = 1.

Expanding these terms gives 3 equations:

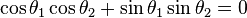

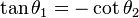

Converting from Cartesian to polar coordinates, and considering Equation  and Equation

and Equation  immediately gives the result r1 = r2 = 1. In other words, requiring the vectors be of unit length restricts the vectors to lie on the unit circle.

immediately gives the result r1 = r2 = 1. In other words, requiring the vectors be of unit length restricts the vectors to lie on the unit circle.

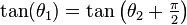

After substitution, Equation  becomes

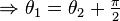

becomes  . Rearranging gives

. Rearranging gives  . Using a trigonometric identity to convert the cotangent term gives

. Using a trigonometric identity to convert the cotangent term gives

It is clear that in the plane, orthonormal vectors are simply radii of the unit circle whose difference in angles equals 90°.

Definition

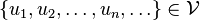

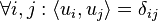

Let  be an inner-product space. A set of vectors

be an inner-product space. A set of vectors

is called orthonormal if and only if

where  is the Kronecker delta and

is the Kronecker delta and  is the inner product defined over

is the inner product defined over  .

.

Significance

Orthonormal sets are not especially significant on their own. However, they display certain features that make them fundamental in exploring the notion of diagonalizability of certain operators on vector spaces.

Properties

Orthonormal sets have certain very appealing properties, which make them particularly easy to work with.

- Theorem. If {e1, e2,...,en} is an orthonormal list of vectors, then

- Theorem. Every orthonormal list of vectors is linearly independent.

Existence

- Gram-Schmidt theorem. If {v1, v2,...,vn} is a linearly independent list of vectors in an inner-product space

, then there exists an orthonormal list {e1, e2,...,en} of vectors in

, then there exists an orthonormal list {e1, e2,...,en} of vectors in  such that span(e1, e2,...,en) = span(v1, v2,...,vn).

such that span(e1, e2,...,en) = span(v1, v2,...,vn).

Proof of the Gram-Schmidt theorem is constructive, and discussed at length elsewhere. The Gram-Schmidt theorem, together with the axiom of choice, guarantees that every vector space admits an orthonormal basis. This is possibly the most significant use of orthonormality, as this fact permits operators on inner-product spaces to be discussed in terms of their action on the space's orthonormal basis vectors. What results is a deep relationship between the diagonalizability of an operator and how it acts on the orthonormal basis vectors. This relationship is characterized by the Spectral Theorem.

Examples

Standard basis

The standard basis for the coordinate space Fn is

{e1, e2,...,en} where e1 = (1, 0, ..., 0) e2 = (0, 1, ..., 0)

en = (0, 0, ..., 1)

Any two vectors ei, ej where i≠j are orthogonal, and all vectors are clearly of unit length. So {e1, e2,...,en} forms an orthonormal basis.

Real-valued functions

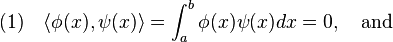

When referring to real-valued functions, usually the L² inner product is assumed unless otherwise stated. Two functions  and

and  are orthonormal over the interval

are orthonormal over the interval ![[a,b]](../I/m/2c3d331bc98b44e71cb2aae9edadca7e.png) if

if

Fourier series

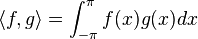

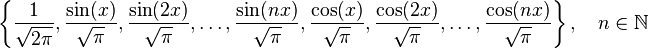

The Fourier series is a method of expressing a periodic function in terms of sinusoidal basis functions. Taking C[−π,π] to be the space of all real-valued functions continuous on the interval [−π,π] and taking the inner product to be

It can be shown that

forms an orthonormal set.

However, this is of little consequence, because C[−π,π] is infinite-dimensional, and a finite set of vectors cannot span it. But, removing the restriction that n be finite makes the set dense in C[−π,π] and therefore an orthonormal basis of C[−π,π].

See also

References

- Axler, Sheldon (1997), Linear Algebra Done Right (2nd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-98258-8

![(2)\quad ||\phi (x)||_{2}=||\psi (x)||_{2}=\left[\int _{a}^{b}|\phi (x)|^{2}dx\right]^{\frac {1}{2}}=\left[\int _{a}^{b}|\psi (x)|^{2}dx\right]^{\frac {1}{2}}=1.](../I/m/c50cba9420cdf3bfc1dcedf76850ea3c.png)