Optical theorem

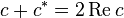

In physics, the optical theorem is a general law of wave scattering theory, which relates the forward scattering amplitude to the total cross section of the scatterer. It is usually written in the form

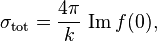

where f(0) is the scattering amplitude with an angle of zero, that is, the amplitude of the wave scattered to the center of a distant screen, and k is the wave vector in the incident direction. Because the optical theorem is derived using only conservation of energy, or in quantum mechanics from conservation of probability, the optical theorem is widely applicable and, in quantum mechanics,  includes both elastic and inelastic scattering. Note that the above form is for an incident plane wave; a more general form discovered by Werner Heisenberg can be written

includes both elastic and inelastic scattering. Note that the above form is for an incident plane wave; a more general form discovered by Werner Heisenberg can be written

Notice that as a natural consequence of the optical theorem, an object that scatters any light at all ought to have a nonzero forward scattering amplitude. However, the physically observed field in the forward direction is a sum of the scattered and incident fields, which may add to zero.

History

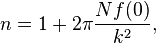

The optical theorem was originally discovered independently by Wolfgang von Sellmeier and Lord Rayleigh in 1871. Lord Rayleigh recognized the forward scattering amplitude in terms of the index of refraction as

(where N is the number density of scatterers) which he used in a study of the color and polarization of the sky. The equation was later extended to quantum scattering theory by several individuals, and came to be known as the Bohr–Peierls–Placzek relation after a 1939 publication. It was first referred to as the Optical Theorem in print in 1955 by Hans Bethe and Frederic de Hoffmann, after it had been known as a "well known theorem of optics" for some time.

Derivation

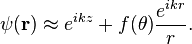

The theorem can be derived rather directly from a treatment of a scalar wave. If a plane wave is incident on an object, then the wave amplitude a great distance away from the scatterer is approximately given by

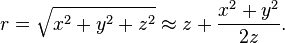

All higher terms, when squared, vanish more quickly than  , and so are negligible a great distance away. For large values of

, and so are negligible a great distance away. For large values of  and for small angles, a Taylor expansion gives us

and for small angles, a Taylor expansion gives us

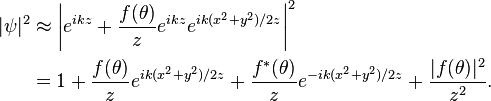

We would now like to use the fact that the intensity is proportional to the square of the amplitude  . Approximating

. Approximating  as

as  , we have

, we have

If we drop the  term and use the fact that

term and use the fact that  , we have

, we have

Now suppose we integrate over a screen in the xy plane, at a distance which is small enough for the small angle approximations to be appropriate, but large enough that we can integrate the intensity from  to

to  with negligible error. In optics, this is equivalent to including many fringes of the diffraction pattern. To further simplify matters, let's approximate

with negligible error. In optics, this is equivalent to including many fringes of the diffraction pattern. To further simplify matters, let's approximate  . We obtain

. We obtain

where A is the area of the surface integrated over. The exponentials can be treated as Gaussians, so

This is the probability of reaching the screen if none were scattered, lessened by an amount ![(4\pi/k)\operatorname{Im}[f(0)]](../I/m/39db78f066663ca355dc7128743fbaf8.png) , which is therefore the effective scattering cross section of the scatterer.

, which is therefore the effective scattering cross section of the scatterer.

References

- R. G. Newton (1976). "Optical Theorem and Beyond". Am. J. Phys 44 (7): 639–642. Bibcode:1976AmJPh..44..639N. doi:10.1119/1.10324.

- John David Jackson (1999). Classical Electrodynamics. Hamilton Printing Company. ISBN 0-471-30932-X.

![|\psi|^2 \approx 1+2\operatorname{Re}{\left[\frac{f(\theta)}{z}e^{ik(x^2+y^2)/2z}\right]}.](../I/m/9df409184bc5b5a22451fbf7662d29f2.png)

![\int |\psi|^2\;dx\,dy \approx A +2\operatorname{Re}\left[\frac{f(0)}{z}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{ikx^2/2z}dx\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} e^{iky^2/2z}dy\right],](../I/m/b8c9e7f7fae61dd42dcff9dece6bf1a2.png)

![\begin{align}

\int |\psi|^2\;da &= A - 2\operatorname{Re}\left[\frac{f(0)}{z}\,\frac{2\pi z}{i k}\right] \\

&= A - \frac{4\pi}{k}\,\operatorname{Im}[f(0)].\end{align}](../I/m/a41b91a20bc18ecd15585b1ccef63d91.png)