Operation Spring

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Operation Spring was an offensive operation conducted by II Canadian Corps during the Normandy campaign. The plan was intended to create pressure on the German forces operating on the British and Canadian front simultaneously to American offensive operations in their sector known as Operation Cobra, an attempt to break out from the Normandy lodgement. Specifically, Operation Spring was intended to capture Verrières Ridge and the towns on the south slope of the ridge.[1] However, strong German defenses on the ridge, as well as strict adherence to a defensive doctrine of counter-attacks, stalled the offensive on the first day, inflicting heavy casualties on the attacking forces, while preventing a breakout in the Anglo-Canadian sector.

Background

Caen was captured on July 19, 1944 during Operation Goodwood, after six weeks of positional warfare throughout Normandy. About 8 kilometers (5.0 mi) south of Caen, Verrières Ridge blocked a direct advance by Allied forces to Falaise.[2] Initial efforts to take the ridge during Goodwood were thwarted by the I SS Panzer Corps, under General Sepp Dietrich.[3] On July 20, 1944, the II Canadian Corps under General Guy Simonds, attempted a similar offensive, codenamed Operation Atlantic. Although initially successful, strong counter-attacks by Dietrich's Panzer Divisions caused the offensive to stall, inflicting 1,349 casualties on Canadian forces.[4]

Plan

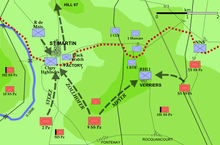

The second phase required the Calgary Highlanders to move from St. Martin to capture May-Sur-Orne and Bourguebus Ridge, thus securing the flanks of Verrières Ridge. In the third phase, the Black Watch would move from Hill 61 to St. Martin, assemble, and attack Verrières Ridge with tank and artillery support.[5] In the fourth phase, Simonds would move in armor and artillery to reach the final objectives south of the ridge, thus making a bulge in German lines and increasing the chance of a breakout from Normandy. Each phase of the plan required precise timing. If any phase of the plan was off, it could result in total disaster.

German Preparations

The Germans were expecting further attacks on Verrières Ridge and consequently reinforced Verrières Ridge in the days preceding the attack. By the end of July 24, 480 tanks, 500 field guns, and four more infantry battalions had been moved into the sector.[4] Ultra intercepted coding signalling this, and delivered it to Simond's HQ, although it is unknown if he actually received the notice.

Battle

Phase I

On July 25, at 0330, The North Nova Scotia Highlanders attacked Tilly-la-Campagne. Simonds had developed a complex lighting system using spotlights reflected off of clouds, thus allowing the North Novas to see the enemy positions. This also meant that the North Novas were clear targets for German defenders and were forced to fight ferociously to gain ground. By 0430, a flare was fired by the lead companies, indicating that the objective had been taken. Within the next hour, Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Petch began to move reinforcements into the village to assist with "mopping up" the last German defenders.

To their west, the The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, although encountering stiff initial opposition, managed to secure Verrières Village by 0530. At 0750, Lt.-Col. John Rockingham reported to Simonds that his battalion had firmly entrenched themselves in the objective.

Phase II

On July 25, the Calgary Highlanders attempted assaults on May-sur-orne and Bourguebus Ridge but found that the assembly area of St. Martin was still occupied by German troops. Two companies of Calgary Highlanders bypassed St. Martin and reached the outskirts of May-Sur-Orne.[4] Radio contact was lost after that and both companies had many casualties. Towards the late morning, the Calgary Highlanders secured St. Martin and then attacked Bourguebus Ridge. After two costly attacks, the Calgary Highlanders struggled to hold onto May-Sur-Orne.

Phase III

Phase III required careful timing, two attempts by the Essex Scottish Regiment and South Saskatchewan Regiment, had been costly failures. Unfortunately for the Black Watch, things went wrong right from the start. Their armour and artillery support never did show up (or when it did, was cut to pieces), and they were four hours late reaching their assembly area of St. Martin [the Black Watch ran into heavy German resistance moving from Hill 61 to the village]. When they did attack Verrières Ridge, they were subject to vicious counter fire from three sides (The "factory" area south of St. Martin, Verrières Ridge itself, and German units on the other side of the Orne). Within minutes, communications had broken down, and the Black Watch lost all but 15 of its attacking soldiers. It marked the bloodiest day for Canadian forces since Dieppe.

German counter-attacks

For several days German forces, mainly the 9th and 12th SS Panzer divisions, continued to chip away at Canadian positions gained in Operation Spring. The Calgary Highlanders eventually pulled out of May-sur-Orne and the North Nova scotia Regiment were forced to retreat from Tilly-la-Campagne. German forces immediately counter-attacked at Verrières Village, but were beaten back. Over the next two days, the RHLI fought "fanatically" to defend the ridge, fending off dozens of counter-attacks. Rockingham relied on well-placed antitank guns and machine-gun positions, fighting off the forces of the two panzer divisions. On July 26, German commanders declared "If you cross the ridge, you are a dead man" to soldiers being deployed on the southern slope of Verrières. In their holding of the town, the RHLI took over 200 casualties. German counter-attacks managed to force the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, Calgary Highlanders and the Black Watch to retreat from May-sur-Orne and St. Martin. The Black Watch support company and the Calgary Highlanders suffered many casualties as they were forced back from their positions.[1]

Aftermath

Analysis

Operation Cobra began on the same day by coincidence and the German high command was unsure which was the main operation. Operation Spring was taken to be the main effort for about two days, because of the importance they gave to holding ground south of Caen, before realising that Cobra was the principal effort and transferred troops westwards.[6] Operation Totalize and Operation Tractable were launched in August and captured more ground against less opposition.[7] The Official History of the Canadian Army, refers to Spring as a "holding attack" in that it was launched with offensive objectives but also firmly with the intent to delay the redeployment of forces westward.

Thanks in part no doubt to the continued heavy fighting in the Caen sector, the German command was slow to appreciate the fundamental significance of the American attack in the west. Montgomery's fear that the "false start" of Operation "Cobra" on July 24, when bad weather caused action to be suspended after bombing had begun, would give his plan away, proved groundless; the Germans were infatuated enough to believe that the Americans had in fact attempted a major advance, and that their resistance had stopped it in its tracks. When the 7th U.S. Corps launched the real attack, after a great blow by heavy bombers, on July 25, a whole day passed before its seriousness began to be fully understood. Then, on the afternoon of the 26th, von Kluge asked urgently for an armoured division from Armeegruppe "G" in the south of France to help him stem the tide. Simultaneously he resolved to bring down additional infantry divisions from the Fifteenth Army, north of the Seine. But both these areas were too distant to provide immediate aid; and only on the morning of the 27th did von Kluge authorize a movement of troops from the adjacent front of the Second British Army. He then directed that the 2nd Panzer Division, and the headquarters of the 47th Panzer Corps, should move to the area south of St. Lo with all speed. Later in the day the 116th Panzer Division was also ordered west. But it was then too late to prevent an American break-through. On this same day "the decisive actions of the operation took place". That evening the 1st U.S. Infantry Division was on the outskirts of Coutances.This vital delay of forty-eight hours the blood shed in Operation "Spring" had helped to purchase; though that operation certainly did no more than reinforce the already powerful effect of Operations "Goodwood" and "Atlantic". "Spring" was merely the last and not the least costly incident of the long "holding attack" which the British and Canadian forces had conducted, in accordance with Montgomery's plan, to create the opportunity for a decisive blow on the opposite flank of the bridgehead. There had been an urgent strategical need for it; and the urgency was strongly underlined in the Supreme Commander's communications to Montgomery. The opportunity had now been amply created, and the American columns, rolling southward from St. Lo, were grasping it to the full. But the heavy fighting on the Caen front was not yet over.

— Stacey, C.P. Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War, Volume II.[8]

Footnotes

- 1 2 Jarymowycz 2001, pp. 75–87.

- ↑ Bercuson 2004, p. 21.

- ↑ van der Vat 2003, p. 155.

- 1 2 3 Copp 1999.

- ↑ O'Keefe 2007.

- ↑ Buckley 2014, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Zuehlke 2001.

- ↑ Stacey 1960, pp. 195–196.

References

- Books

- Bercuson, D. (2004). Maple leaf Against the Axis. Ottawa: Red Deer Press. ISBN 0-88995-305-8.

- Buckley, J. (2013). Monty's Men: The British Army and the Liberation of Europe (2014 ed.). London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-20534-3.

- Jarymowycz, R. (2001). Tank Tactics; from Normandy to Lorraine. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner. ISBN 1-55587-950-0.

- Stacey, Colonel C. P.; Bond, Major C. C. J. (1960). The Victory Campaign: The Operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War III. Ottawa: The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery. OCLC 606015967. Retrieved 2014-05-19.

- Tout, Ken (2002). Roads to Falaise: 'Cobra' and 'Goodwood' Reassessed. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2822-0.

- van der Vat, D. (2003). D-Day; The Greatest Invasion, A People's History. Toronto: Madison Press. ISBN 1-55192-586-9.

- Zuehlke, M. (2001). The Canadian Military Atlas. London: Stoddart. ISBN 0-7737-3289-6.

- Episode

- O'Keefe, D. (2007). "Black Watch: Massacre at Verrières Ridge". (Toronto: History Television, Alliance Atlantis Communications). Retrieved June 20, 2007. Missing or empty

|series=(help)

- Journals

- Copp, T. (1992). "Fifth Brigade at Verrières Ridge". Canadian Military History Journal 1 (1–2): 45–63. ISSN 1195-8472. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- Copp, T. (1999). "The Toll of Verrières Ridge". Legion Magazine (Ottawa: Canvet Publications) (May/June 1999). ISSN 1209-4331. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- Jarymowycz, R. (1993). "Der Gegenangriff vor Verrières: German Counterattacks during Operation 'Spring': 25–26 July 1944". Canadian Military History Journal 2 (1): 75–89. ISSN 1195-8472. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

Further reading

- Books

- Beevor, A. (2009). D-Day: The Battle for Normandy. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-88703-3.

- Theses

- O'Keefe, D. R. (1997). Bitter Harvest : A Case Study of Allied Operational Intelligence for Operation Spring Normandy, July 25, 1944 (PDF) (MA). Ottawa: University of Ottawa. OCLC 654188049. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Operation Spring. |

| |||||||||||||

Coordinates: 49°06′37″N 0°19′57″W / 49.1104°N 0.3324°W