Jabidah massacre

The Jabidah Massacre was the alleged killing of Moro soldiers by members of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) on March 18, 1968.[1] It was also known as the Corregidor Massacre as the killing took place in Corregidor Island, in the Philippines.

The state, at that point in time, had muffled the affair in the interest of national unity[2] which therefore led to little or no documentation on the incident. This then led to speculations on the number of trainees killed, varying from 11 to 68[3][4] and the reasons behind the massacre.

Some authors[5] believe that the massacre never existed.[6]

Background

The north-eastern part of Sabah had been under the rule of the Sulu Sultanate since been given by the Sultanate of Brunei in 1658 for the latter's help in settling a civil war in Brunei[12] before been "ceded"[13] (in which a translation in Tausug/Philippine Malay translated the word as "padjak")[14] to the British on 1878.[13] During the process of decolonization by the British after World War II from 1946, Sabah was integrated as part of the Malaysian Federation in 1963 under the Malaysia Agreement.[15] The Philippine government however protested this, claiming the eastern part of Sabah had never been sold to foreign interests, and that it had only been leased (padjak) by the Sulu Sultanate, and therefore remained the property of the Sultan, and by extension, the property of Republic of the Philippines. Diplomatic efforts to Malaysia and the United Nations during the administration of President Diosdado Macapagal proved futile. On September 13, 1963, the United Nations held a referendum over Sarawak and Sabah, and the people voted to join to forming the Federation of Malaysia.[16]

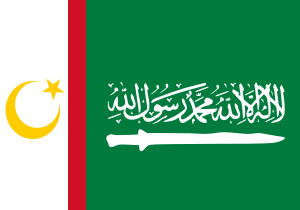

Operation Merdeka

In 1962, President Diosdado Macapagal renewed Philippine’s 1922 claim over Sabah although the territory has been incorporated into Malaysia. Operation Merdeka is a follow-up to this claim. The alleged plan was for trained commandos to infiltrate Sabah and destabilise the state by sabotage which would then legitimise Philippine’s military intervention in the territory and claiming the state which many Filipinos felt was rightfully theirs.[17]

| Operation Merdeka | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of North Borneo dispute | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

• | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

In 1967, President Ferdinand Marcos secretly authorised Major Eduardo “Abdul Latif” Martelino, who was a Muslim convert, to take charge of the operations of the ultra-secret parliamentary unit code-named Operation Merdeka (merdeka meaning "freedom" in Malay). The alleged mastermind, however, included leading generals in the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), Defense Undersecretary Manuel Syquio, and Marcos himself.[3]

The first phase of the operation saw Martelino, with an advanced party of some 17 agents entering Sabah for 3 times to demolish their equipment, plant dynamites, and etc. It was during the second phase of the operation that the massacre took place. After 180 young Tausugs from Sulu received basic training, they were transported to a remote section of Corregidor Island at the mouth of Manila Bay[17] where they were further trained in guerrilla operations and jungle warfare. Once on the island, the code name was changed to ‘Jabidah’.[3] The real purpose of the formation of Jabidah was never publicised therefore leading to wide speculations and controversies regarding this top secret military plan.[18]

The massacre

There are various accounts on the massacre. One camp believes that the mutiny of the recruits who were angered by the delay in receiving their allowance led to the massacre.[3][17][18] The poor living condition, and miserable rations for three months led to general discontent amongst the Muslim trainees who then demanded to be returned home. The recruits were disarmed, some were returned back home and some were transferred to a normal military camp in Luzon but on March 18, one of the two batches of recruits who were supposed to be released were killed by regular army troops.[3] The lone survivor, Jibin Arula, who managed to escape the mayhem with just a gunshot wound on his leg recounted the atrocity but scholars have analysed that the media attention on Arula may have, to some extent, distorted his accounts.[19] The actual happening remains unclear as documents were allegedly destroyed by Major Martellino.[3]

On the flipside, another camp believes that the project code-named Jabidah involved the recruitment of Muslims trainees who were supposed to be trained to infiltrate and cause chaos in Sabah to strengthen Philippines’ territorial claim.[20] However, these trainees were informed beforehand that they were joining the AFP to fight the “communists” but subsequently learned of their real mission during the latter part of their training.[21] Within this camp, some scholars argue that the massacre was due to the mutiny of the Muslim trainees who denied orders to infiltrate Sabah because they felt that the sabotage against Sabah was unjustified and that they also felt the connected with the fellow Muslims in Sabah.[22] While other scholars argue that the trainees were killed upon learning the truth of their recruitment to ensure that the information was not leaked.[23]

The official narrative denied that the reason for training the recruits were for infiltration in Sabah and that the massacre as stated in the Manila Bulletin, the government-controlled leading print media, occurred because the trainees could not endure hardship during the training.[24]

With the lack of substantial evidence, the officers involved in the massacre were unable to be put to trial and thus acquitted which further angered the Muslims.[25][26]

Aftermath

Political play

The opposition senator Benigno Aquino, Jr. exposed that Jabidah was a plan by President Ferdinand Marcos to ensure his continuity of power.[5][27] The incident was used by members of the opposition to criticise Marcos administration and this was largely covered by the press which caught the government off-guard.[21] The massacre can be seen as a political tool by the opposition to discredit the President Ferdinand Marcos for his poor administration and negligence of the Muslims during his term.[28]

International attention

The Jabidah Massacre was so heavily publicised by the media that the government received flak from the international community, especially the Muslim countries.[21] In July 1971, then Prime Minister of Libya, Muammar Gaddhafi, wrote to President Marcos to express his concern. As Philippines relied on Arab oil, the government tried to defend itself against any accusation and denied any religious repression taking place in Mindanao. The acting foreign Minister added that the problems stemmed from land and political issues which it was ready to solve internally.[26]

Then Prime Minister of Malaysia, Tunku Abdul Rahman, also condemned the Philippines government and requested for congressional trial against the officers involved in the massacre.[3] Diplomatic ties between Philippines and Malaysia were severed[26] as this event also further indicated to Malaysia that Philippines’ government still had strong determination to annex the Malaysian state.[21]

In general, this affair had increased the international community’s awareness of the Moro issue in the Philippines.[26]

Protest and formation of the Muslim Independence Movement (MIM)

Many scholars agree that the Jabidah Massacre was one of the most important events in Philippines that ignited the Muslims uprising during Marcos’ regime[29] notwithstanding the truth behind the massacre.

Despite undergoing numerous trials and hearings, the officers related to the massacre were never convicted and which was a clear indication to the Muslim community that the Christian government had little regard for them.[30] This created a furore within the Muslim community in the Philippines, especially among the educated youth sector.[21] The Muslims students saw the need through this incident to unite in protest and organised demonstrations and rallies in Manila with financial backing from the Muslim politicians and university intellectuals. One such demonstration was situated near the Malacañang Palace, where the President and his family resided. The students held a week-long protest vigil over an empty coffin marked ‘Jabidah’ in front of the palace.[2]

The massacre significantly brought the Muslim intellectuals, who prior to the incident had no discernible interest in politics, into the political scene to demand for safeguard against politicians who were using them as convenience for high stakes.[31] Apart from the intellectuals, Muslims in Philippines in general saw that all opportunities for integration and accommodation with the Christians lost and were further marginalised.[3]

In May 1968, former Cotabato governor Datu Udtog Matalam announced the formation of the Muslim Independence Movement (MIM) which was regarded by observers as the spontaneous backlash of the Jabidah Massacre.[32] The strong feelings and unity of the Muslim intellectuals were seen as the immediate reaction to the establishment of the MIM[33] which carried far-reaching impacts such as the formation of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and continued armed struggle in Southern Philippines till today.

Official acknowledgement

President Benigno Aquino III acknowledged the incident on March 18, 2013, when he leading commemorations on the 45th anniversary of the massacre. This notably marked the first time that a ruling President had acknowledged the massacre as having taken place. Aquino also directed the National Historical Commission of the Philippines to designate the Mindanao Garden of Peace on Corregidor as a historical landmark.[34]

Contradiction

Contrary to the claim of his son President Benigno Aquino III, his father, the late senator, Benigno Ninoy Aquino Jr., a staunch critic of Marcos and a prominent opposition leader, conducted his own investigation and went as far to where it all started-in Sulu, where he found out that the 11 other recruits named by the sole witness Jibin Arula where all alive.

Ninoy Aquino did not expose the Jabidah massacre but refuted it with clear evidences he gathered after his investigation. He categorically declared in his speech in the Senate that the alleged massacre is a hoax (see Ninoy Speech: Jabidah! Special Forces of Evil delivered in the Philippine Senate on March 28, 1968)

A Portion of Senator Ninoy Aquino Senate Speech:

| “ | "This morning, the Manila Times, in its banner headline, quoted me as saying that I believed there was no mass massacre on Corregidor island.

And I submit it was not a hasty conclusion, but one borne out by careful deductions. What brought me to this conclusion:

|

” |

In popular cultures

A film based on the event was released in 1990 starring Anthony Alonzo. It shares the same name however details are fictionalized for the sake of the film.[36]

See also

References

- ↑ Marites Dañguilan Vitug; Glenda M. Gloria (18 March 2013). "Jabidah and Merdeka: The inside story". Rappler. Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- 1 2 Majul, Cesar (1985). The Contemporary Muslim Movement in the Philippines. Mizan Press. pp. 43–44.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Rodell, Paul (2005). "The Philippines and the Challenge of Terrorism". In Smith, Paul. Terrorism and Violence in Southeast Asia: Transnational Challenges to States and Regional Stability. M. E. Sharpe, Inc. pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Asani, Abdurasad (1985). "The Bangsamoro People: A Nation in Travail". Journal Institute of Muslim Minority Affairs.

- 1 2 Senator Benigno S. Aquino Jr. (28 March 1968). "Jabidah! Special Forces of Evil?". Delivered at the Legislative Building, Manila, on 28 March 1968. Government of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ↑ Andrew Tian Huat Tan numbers the victims between 28 and 64, and says that author and social anthropologist Arnold Molina Azurin has written that the massacre is a myth.[7] William Larousse says that a survivor described recruits being shot in groups of twelve. Note 5 on page 130 gives a number of estimates by other sources ranging from 14 to 64.[8] Authors at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies say that Jibin Arula, described as the sole survivor of the massacre, as numbering his fellow trainees killed at 11, while others numbered them at over 60.[9] Alfred W. McCoy puts Arula in a second group of 12 recruits taken to be killed, and describes his escape.[10] Artemio R Guillermo puts the number of recruits at "about two hundred" and says that only one man escaped being massacred.[11]

- ↑ Andrew Tian Huat Tan (2007). A handbook of terrorism and insurgency in Southeast Asia. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 199, 219. ISBN 978-1-84542-543-2.

- ↑ William Larousse; Pontificia Università gregoriana. Centre "Cultures and Religions." (2001). A local Church living for dialogue: Muslim-Christian relations in Mindanao-Sulu, Philippines : 1965-2000. Editrice Pontificia Università Gregoriana. p. 130. ISBN 978-88-7652-879-8.

- ↑ Michael Leifer; Kin Wah Chin; Leo Suryadinata; Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (2005). Michael Leifer: selected works on Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 674. ISBN 978-981-230-270-0. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Alfred W. McCoy (2009). Policing America's empire: the United States, the Philippines, and the rise of the surveillance state. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 390–391. ISBN 978-0-299-23414-0.

- ↑ Artemio R. Guillermo (December 16, 2011). Historical Dictionary of the Philippines. Scarecrow Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-8108-7511-1.

- ↑ Rozan Yunos (7 March 2013). "Sabah and the Sulu claims". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 17 June 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- 1 2 British Government (1878). "British North Borneo Treaties. (British North Borneo, 1878)" (PDF). Sabah State Government (State Attorney-General's Chambers). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ↑ Chester Cabalza. "The Sabah Connection: An Imagined Community of Diverse Cultures". Academia.edu. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ↑ "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and Federation of Malaya, North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore (Agreement relating to Malaysia)" (PDF). United Nations. 1963. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ↑ "United Nations Malaysia Mission Report, "Final Conclusions of the Secretary-General"". United Nations Malaysia Mission Report. Government of the Philippines. 14 September 1963. Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 McCoy, Alfred (2009). Policing America’s Empire: The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State. The University of Wisconsin Press. p. 390.

- 1 2 Majul, Cesar (1985). The Contemporary Muslim Movement in the Philippines. Berkley: Mizan Press. p. 40.

- ↑ Curaming, Rommel; Aljunied, Khairudin (2013). "On the Fluidity and Stability of Personal Memory: Jibin Arula and the Jabidah Massacre in the Philippines". In Loh, Kah Seng; Dobbs, Stephen; Koh, Ernest. Oral History in Southeast Asia: Memories and Fragments. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 84–89.

- ↑ Banlaoi, Rommel (2007). "'Radical Muslim Terrorism' in the Philippines". In Tan, Andrew. A Handbook of Terrorism and Insurgency in Southeast Asia. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. p. 199.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Muslim, Macapado (1994). The Moro Armed Struggle in the Philippines: The Nonviolent Autonomy Alternative. Office of the President and College of Public Affairs, Mindanao State University. pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Noble, Lela Garner (1976). "The Moro National Liberation Front in the Philippines". Pacific Affairs: 405–424.

- ↑ Gross, Max L. (2007). A Muslim Archiepelago: Islam and Politics in Southeast Asia. Center for Strategic Intelligence Research. p. 183.

- ↑ Islam, Syed Serajul (1998). "The Islamic Independence Movements in Patani of Thailand and Mindanao of the Philippines". Asian Survey.

- ↑ Wurfel, David (1988). Domestic Policy: Agrarian Reform and the Search for National Unity. Cornell University Press. p. 156.

- 1 2 3 4 Yegar, Moshe (2002). Between Integration and Secession: The Muslim Communities of the Southern Philippines, Southern Thailand and Western Burma / Myanmar. Lexington Books. pp. 251–257.

- ↑ Marohomsalic, Nasser A. (1995). Aristocrats of the Malay Race: A History of Bangsa Moro in the Philippines. Lanao Del Sur: Mindanao State University. p. 164.

- ↑ Buendia, Rizal G. (2002). Ethnicity and Sub-nationalist Independence Movements in the Philippines and Indonesia: Implications for Regional Security. Yuchengo Center, De La Salle University. pp. 38–39.

- ↑ George, T. J. S. (1980). Revolt in Mindanao: The Rise of Islam in Philippines Politics. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. p. 122.

- ↑ Larousse, William (2001). A Local Church Living for Dialogue: Muslim-Christian Relations in Mindanao-Sulu (Philippines) 1965-2000. Editrice Pontificia Universita Gregoriana. p. 131.

- ↑ George, T. J. S. (1980). Revolt in Mindanao: The Rise of Islam in Philippines Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 129.

- ↑ George, T. J. S. (1980). Revolt in Mindanao: The Rise of Islam in Philippines Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 133.

- ↑ May, R. J. (1981). "The Philippines". In Ayoob, Mohammed. The Politics of Islamic Reassertion. London: Croom Helm. p. 218.

- ↑ "Noynoy insists Jabidah massacre true, wants it in history books". The Daily Tribune. House of Representatives of the Philippines. 19 March 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

- ↑ ""Jabidah! Special Forces of Evil?" by Senator Benigno S. Aquino Jr.". Government of the Philippines. March 28, 1968.

- ↑ Jerry O. Tirazona. "Jabidah Massacre (1990 film)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 13 September 2015.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||