Operativo Independencia

| Operativo Independencia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Part of the Dirty War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Acdel Vilas Antonio Domingo Bussi |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5.000 (1975) |

ERP:

Montoneros:

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

~70 killed

|

~312 guerrillas killed Hundreds missing | ||||||

Operativo Independencia (Spanish for "Operation Independence") was the code-name of the Argentine military operation in the Tucumán Province, started in 1975 to crush the ERP —Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo or People's Revolutionary Army—, a Guevarist guerrilla group, which tried to create a Vietnam-style war front in the Tucumán Province, in northwestern Argentina. It was the first large-scale military operation of the Dirty War.

Prologue

After the return of Juan Perón to Argentina, marked by the 20 June 1973 Ezeiza massacre which led to the split between left and right-wing Peronists, and then his return to the presidency in 1973, the ERP shifted to a rural strategy designed to secure a large land area as a base for military operations against the Argentine state. The ERP leadership chose to send "Compañía de Monte Ramón Rosa Jiménez" to the province of Tucumán at the edge of the long-impoverished Andean highlands in the northwest corner of Argentina. By December 1974, the guerrillas numbered about 100 fighters, with a 400-person support network, although the size of the guerrilla platoons increased from February onwards as the ERP approached its maximum strength of between 300 and 500 men and women. Led by Mario Roberto Santucho, they soon established control over a third of the province and organized a base of some 2,500 sympathizers.[3] The Montoneros' leadership was keen to learn from their experience, and sent "observers" to spend a few months with the ERP platoons operating in Tucumán.[4]

February 1975 "annihilation decree"

The military operation to crush the insurgency was authorized by the President of the lower house, Ítalo Argentino Lúder, who was granted executive power during the absence (due to illness) of the President María Estela Martínez de Perón, better known as Isabel Perón, in virtue of the "Ley de Acefalía" (law of succession). Ítalo Lúder issued the presidential decree 261/1975 which stated that the "general command of the Army will proceed to all of the necessary military operations to the effect of neutralizing or annihilating the actions of the subversive elements acting in Tucumán Province."[5]

The Argentine military used the territory of the smallest Argentine province to implement, within the framework of the National Security Doctrine, the methods of the "counter-revolutionary warfare". These included the use of terrorism, kidnappings, forced disappearances and concentration camps where hundreds of guerrillas and their supporters in Tucumán were tortured and murdered. The logistical and operational superiority of the military, headed first by General Acdel Vilas, and starting in December 1975 by Antonio Domingo Bussi, succeeded in crushing the insurgency after a year and by destroying links the ERP, led by Roberto Santucho, had earlier established with the local population.

Brigadier-General Acdel Vilas deployed over 4,000 soldiers, including two companies of elite army commandos, backed by jets, dogs, helicopters, US satellites[6] and a Navy's Beechcraft Queen Air B-80 equipped with IR surveillance assets.[7] The ERP did not enjoy much support from the local population and it needed to wage a terror campaign to be able to move at will among the towns of Santa Lucía, Los Sosa, Monteros and La Fronterita[8] around Famaillá and the Monteros mountains, until the Fifth Brigade came on the scene, consisting of the 19th, 20th and 29th Regiments.[9] and various support units.

Generalization of the state of emergency

During his brief interlude as the nation's chief executive, interim President Ítalo Lúder extended the operation to the whole of the country through Decrees noº 2270, 2271 and 2272, issued on 6 July 1975. The July decrees created a Defense Council headed by the president, and including his ministers and the chiefs of the armed forces.[10][11][12] It was given the command of the national and provincial police and correctional facilities and its mission was to "annihilate … subversive elements throughout the country". Military control and the state of emergency was thus generalized to all of the country. The "counter-insurgency" tactics used by the French during the 1957 Battle of Algiers —such as relinquishing of civilian control to the military, state of emergency, block warden system (quadrillage), etc.— were perfectly imitated by the Argentine military.

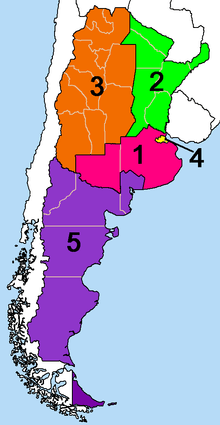

These "annihilation decrees" are the source of the charges against Isabel Perón, which called for her arrest in Madrid more than thirty years later, in January 2007, but she was never extradited to Argentina due to her advanced age. The country was then divided into five military zones through a 28 October 1975 directive of "Struggle Against Subversion". As had been done during the 1957 Battle of Algiers, each zone was divided in subzones and areas, with its corresponding military responsibles. General Antonio Domingo Bussi replaced Acdel Vilas in December 1975 as responsible of the military operations. A reported 656 persons disappeared in Tucumán between 1974 and 1979, 75% of which were laborers and labor union officials.[13]

The military operation

1975

The deployment was completed by 9 February. The guerrillas who had laid low when the mountain brigade first arrived, soon began to strike at the commando units. It was during the second week of February that a platoon from the commando companies was ambushed at Río Pueblo Viejo, resulting in the deaths of an NCO and two guerrillas. On 24 February, while supporting troops on the ground, a Piper PA-18 crashed near the town of Ingenio Santa Lucía, killing its two crewmen.[14] On 28 February, an army corporal [15] was killed while inspecting an abandoned car rigged with an explosive charge in the city of Famaillá.

Three months of constant patrolling and 'cordon and search' operations with helicopter-borne troops, soon reduced the ERP's effectiveness in the Famaillá area, and so in June, elements of the 5th Brigade moved to the frontiers of Tucumán to guard against ERP and Montoneros guerrillas crossing into the province from Catamarca, and Santiago del Estero.

On 11 May, an Army NCO[16] was killed during a fierce exchange of fire with guerrillas on Route 301 in Tucumán. That month, ERP representative Amílcar Santucho, brother of Roberto, was captured along with Jorge Fuentes Alarcón, a member of the Chilean MIR, trying to cross into Paraguay to promote the Revolutionary Coordinating Junta (JCR, Junta Coordinadora Revolucionaria) unity effort with the MIR, the Uruguayan Tupamaros and the Bolivian National Liberation Army. During his interrogation, he provided information that helped the Argentine security agencies destroy the ERP.

On 28 May, a 8-hour gun battle took place between 114 guerrillas and 14 soldiers in Manchalá, without casualties on either side. Nevertheless, the guerrillas hastily escaped, leaving behind vehicles, weapons and documentation, which enabled the army to take the upper hand.

A 6 June 1975 letter from the United States Justice Department revealed that Robert Scherrer, a FBI official, passed on information revealed by the two men to the Chilean DINA. By this point, Operation Condor, the campaign of repressive cooperation between Latin American intelligence agencies, was already being planned, the third phase of which included assassinations of political opponents in Latin America and abroad. Fuentes was then "released" and sent to Chile, where he was last seen in the torture center Villa Grimaldi before becoming a desaparecido.[17]

By July, the commandos were carrying out search-and-destroy missions in the mountains. Army special forces discovered Santucho's hideout in August, then raided the ERP urban headquarters in September.

Nevertheless, the military was not to have everything its own way. On 28 August, a bomb was planted at the Tucumán air base airstrip by Montoneros, in a support action for their comrades in the ERP. The blast destroyed an Air Force C-130 transport carrying 114 anti-guerrilla Gendarmerie commandos heading for home leave, killing six[18] and wounding 29.[19] The following day saw the derailment of a train carrying troops back from the guerrilla front about 64 kilometers south of the city of Tucumán, this time without any casualties.[20]

Most of the Compañía de Monte's general staff were killed in a special forces raid in October, but the guerrilla unit continued to fight. Between 7 and 8 October 1975, six soldiers[21] were killed during an ambush.

On 10 October, a UH-1H helicopter was hit by small arms fire during an offensive reconnaissance mission, killing its door gunner. After an emergency landing, other helicopters carried out rocket attacks on the reedbed. A total of 13 guerrillas were killed in the ensuing firefight.[22] On 17 October, near Los Sosas, an army platoon was ambushed, and lost four men. On 24 October, during a night mission that took place on the banks of Fronterista River, three men from the 5th Brigade were killed.[23] Between 8 and 16 November 1975, there were other engagements in which the 5th Brigade suffered another three losses.[24]

On 18 December, Acdel Vilas was relieved from his post and Antonio Domingo Bussi assumed command of the operations. Shortly afterwards, Bussi told Vilas over the phone: "Vilas, you have left me nothing to do."

On 29 December, Bussi launched Operation La Madrid I, the first of a series of four search and destroy operations.

1976

The mountain and parachute units remained essential as military support for the local police and gendarmerie security forces, and for the apprehension of several hundred ERP and Montoneros guerrillas who still remained operating in the jungles and mountains, and sympathizers hidden among the civilian population in what was described by the Baltimore Sun as a "growing 'Viet war'"[25] During the first week of January, the army commandos discovered seven guerrilla hideouts.

During February 1976, in an effort to rekindle the rural front in Tucumán, Montoneros sent in reinforcements in the form of a company of their elite "Jungle Troops", which was initially commanded by Juan Carlos Alsogaray (El Hippie), son of General Julio Alsogaray, who had served as head of the Argentine Army from 1966 to 1968. The ERP also sent reinforecment to Tucumán in the form of their elite "Decididos de Córdoba" Company from Córdoba.[26] Bussi achieved a major success on 13 February, when the 14th Airborne Infantry Regiment killed el Hippie and ambushed his elite Montoneros company. Two soldiers[27] and around 10 guerrillas were killed in this action.

On 30 March, a police officer was gunned down while patrolling in downtown Tucumán.

On 10 April, a private [28] was killed in a guerrilla ambush in Tucumán. That same day, a policeman was killed while standing guard at a hospital. In mid-April, the 4th Airborne Infantry Brigade in a major operation conducted against the ERP underground network in the province of Córdoba, took into custody and forcibly disappeared some 300 militants of that organization.[29] On 26 April 1976, inspector general Juan Sirnio of the Tucumán police force is shot dead by the Montoneros guerrilla force supporting ERP operations in the province, according to the Centre for Legal Studies on Terrorism and its Victims (Celtyv) in Argentina .[30]That same day, the Montoneros guerrillas also kill Colonel Abel Héctor Elías Cavagnaro outside his home in Tucumán.[31][32]

On 5 May, during an armed reconnaissance mission, an army UH-1H crashed on the banks of Río Caspichango, killing five men.[33] On 7 May, in a gunfight close to a river, another corporal[34] was killed in a guerrilla ambush. On 10 May, Private Carlos Alberto Fricker was accidentally shot dead by nervous sentries while stationed in Famaillá or committed suicide, although journalist Marcos Taire in his article guerra que no tuvo héroes (war that had no heroes) suggested the Argentine Army was involved in a dastardly action.[35]

On 17 May, two soldiers[36]died in a remote-controlled bomb blast near the town of Caspinchango, which was carried out by the guerrillas.[37][38][39]Nevertheless, in 2013 journalist Marcos Taire who appeared in the El Azúcar y la Sangre 2007 documentary praising the leftist militants in Tucumán, wrote that the Argentine military campaign in the province was a hoax and that the ambulance was blown up on purpose in an Argentine Army false-flag incident.[40]

In early October, the Compañía de Monte's commander, Lionel MacDonald, was gunned down along with another two guerrillas.

Thorough 1976, a total of 24 patrol battles took place, resulting in the deaths of at least 74 guerrillas and 18 soldiers and policemen in the province of Tucumán.[41]

Veterans' recognition demands

On 14 December 2007, some 200 soldiers who fought against the guerrillas in Tucumán province demanded an audience with the governor of Tucumán Province, José Jorge Alperovich, claiming they too were victims of the "Dirty War", and demanded a government sponsored military pension as veterans of the counter-insurgency campaign in northern Argentina.[42] Indeed, data from the 2,300-strong Asociación Ex-Combatientes del Operativo Independencia indicate that as of 1976, 4 times more Tucumán veterans have died from suicide after operations in the province. Critics of the ex-servicemen association claim that no combat operations took place in the province and that the government forces deployed in Tucumán killed more than 2,000 innocent civilians.[43] According to Professor Paul H. Lewis, a large percentage of the disappeared in Tucumán were in fact students, professors and recent graduates of the local university, all of whom were caught providing supplies and information to the guerrillas.[44] On 24 March 2008, some 2,000 Tucumán veterans of the 11,000-strong Movimiento Ex Soldados del Operativo Independencia y del Conflicto Limítrofe con Chile, who fought against ERP guerrillas and were later redeployed along the Andes in the military standoff with Chile, took to the streets of Tucumán city to demand recognition as combat veterans.[45] Some 180,000 Argentine conscripts saw service during the military dictatorship (1976-1983),[46] 130 died as a result of the Dirty War.[47]

See also

- Battle of Algiers (1957)

- Dirty War

- Isabel Perón

- Marie-Monique Robin's documentary (on the relationship between the French military and their Argentine counterparts)

- People's Revolutionary Army

- Ítalo Lúder

References

- ↑ "Operativo Justicia por el Operativo Independencia" (in Spanish). Página/12. 29 December 2012.

- ↑ Susan Eckstein (2001). Poder y protesta popular: Movimientos sociales latinoamericanos. Siglo XX. p. 276.

(Spanish): El 28 de septiembre de 1977 el mando militar en la provincia de Tucumán informó que las guerrillas del ERP que realizaban operaciones en aquella zona habían sido aniquiladas.

- ↑ Lewis, Paul H. (2002). Guerrillas and Generals: The Dirty War in Argentina. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 105.

- ↑ Martha Crenshaw (1995). Terrorism in Context,. Penn State Press. p. 230.

- ↑ Decree No. 261/75. NuncaMas.org, Decretos de aniquilamiento. Spanish: El Comando General del Ejército procederá a ejecutar todas las operaciones militares que sean necesarias a efectos de neutralizar o aniquilar el accionar de los elementos subversivos que actúan en la provincia de Tucumán.

- ↑ Comandos en acción: el Ejército en Malvinas, Isidoro Ruiz Moreno, p. 24, Emecé Editores, 1986

- ↑ Burzaco, Ricardo: (1994). Infierno en el Monte Tucumano. p. 64. OCLC 31720152.

- ↑ Lewis, Paul H. (2002). Guerrillas and Generals: The Dirty War in Argentina. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 107.

- ↑ English, Adrian J. (1984). Armed Forces of Latin America: Their Histories, Development, Present Strength, and Military Potential. Janes Information Group. p. 33.

- ↑ Decree No. 2770/75. NuncaMas.org, Decretos de aniquilamiento.

- ↑ Decree No. 2771/75. NuncaMas.org, Decretos de aniquilamiento.

- ↑ Decree No. 2772/75. NuncaMas.org, Decretos de aniquilamiento.

- ↑ "Listado de Desaparecidos" (in Spanish). Proyecto Desaparecidos.

- ↑ First Lieutenant Carlos María Casagrande and Second Lieutenant Gustavo Pablo López

- ↑ Desidero Dardo Pérez.

- ↑ Second Lieutenant Raúl Ernesto García.

- ↑ John Dinges. "Operation Condor". Fathom archive of Columbia University.

- ↑ Sergeants Juan Rivero and Pedro Yáñez and Corporals Marcelo Godoy, Raúl Cuello, Juan Luna and Evaristo Gómez

- ↑ "35 años del atentado al Hércules en Tucumán".

- ↑ "Airport Terrorists Sought In Argentina". Toledo Blade. 29 August 1975.

- ↑ First Corporal José Anselmo Ramírez and privates Pío Ramón Fernández, Rogelio René Espinosa, Juan Carlos Castillo, Enrique Ernesto Guastoni and Fredy Ordoñez.

- ↑ "Argentine Army Claims 13 Leftist Guerrillas Killed". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. 12 October 1975.

- ↑ Second Lieutenant Diego Barceló and Privates Orlando Aníbal Moya and Carlos Humberto Vizcarra

- ↑ First Corporal Wilfredo Napoleón Méndez and privates Benito Edgar Pérez and Miguel Arturo Moya

- ↑ James Nelson Goodsell (18 January 1976). "'Viet war' growing in Argentina". The Baltimore Sun.

- ↑ Lewis, Paul H. (2002). Guerrillas and Generals: The Dirty War in Argentina. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 125.]

- ↑ Corporal Héctor Roberto Lazarte and Private Pedro Burguener

- ↑ Private Mario Gutiérrez

- ↑ Robben, Antonius C. G. M. (2005). Political Violence and Trauma in Argentina. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 201.

- ↑ Los Otros Muertos: Las Víctimas Civiles del Terrorismo Guerrillero de los 70, Carlos A. Manfroni, Victoria E. Villarruel, Page 189, Grupo Editorial Argentina (1 April 2014)

- ↑ Las Cifras de la Guerra Sucia, Graciela Fernández Meijide, Page 52, Asamblea Permanente por los Derechos Humanos, (1988)

- ↑ Documentos, 1976-1977: Golpe Militar y Resistencia Popular, Roberto Baschetti, Page 21, De la Campana (2001) "Un comando montonero abate al coronel (RE) Abel Héctor Elías Cavagnaro en la puerta de su casa."

- ↑ Captain José Antonio Ramallo, Lieutenant César Gonzalo Ledesma, Sergeant Walter Hugo Gómez and Corporals Carlos Alberto Parra and Ricardo Zárate

- ↑ Corporal Ricardo Martín Zárate

- ↑ guerra que no tuvo héroes

- ↑ Sergeant Alberto Eduardo Lai and Private Juan Ángel Toledo

- ↑ Guerrillas and Generals: The "Dirty War" in Argentina, Paul H. Lewis, Page 126, Greenwood Publishing Group (2002) "Throughout April and May, the Mountain Company tried to regain the initiative by shooting down a helicopter, blowing up an army ambulance, executing an army scout, and raking with gunfire a squad of soldiers in a truck, but the army's pressure was inexorable."

- ↑ ISLA, Volume 12, Page 126, ISLA Clipping Service (1976) "Elsewhere, the dynamiting of an army ambulance and a shootout left Seven guerrillas and three soldiers dead."

- ↑ Peron faces interrogation (May 19,1976)

- ↑ guerra que no tuvo héroes

- ↑ "Operativo Independencia" (in Spanish).

- ↑ "Ex soldados exigen una pensión" (in Spanish). El Siglo. 15 December 2007.

- ↑ "Volvieron a aparecer públicamente los ex soldados que reivindican el Operativo Independencia" (in Spanish). 11 February 2009.

- ↑ Lewis, Paul H. (2002). Guerrillas and Generals: The Dirty War in Argentina. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 126.

- ↑ El Siglo, 24 March 2008

- ↑ "Estafan a ex soldados con rumores de pensiones: cobran $ 500 por trámite" (in Spanish). Clarín.com. 3 July 2007.

- ↑ Duhalde, Eduardo Luis (1999). El estado terrorista argentino: Quince años después, una mirada crítica. Eudeba. p. 339.