Omega Speedmaster

|

Omega Speedmaster Professional Ref. 145.012 | |

| Manufacturer | Omega |

|---|---|

| Also called | Moonwatch |

| Introduced | 1957 |

| Movement | Omega caliber 321, 861, 1861, others |

Omega Speedmaster is a line of chronograph wristwatches produced by the Omega Watch Company. While Chronographs have been around since the late 1800s, Omega first introduced this line of chronographs in 1957. Since then, many different chronograph movements have been marketed under the Speedmaster name. The manual winding Speedmaster Professional or "Moonwatch" is the best-known and longest-produced; it was worn during the first American spacewalk as part of NASA's Gemini 4 mission and was the first watch worn by an astronaut walking on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission.[1][2] The Speedmaster Professional remains one of several watches qualified by NASA for spaceflight and is still the only one so qualified for EVA.[3] The Speedmaster line also includes other models, including analog-digital and automatic mechanical watches.[4][5]

Early development

The Speedmaster was not originally designed for space exploration. Instead, it was introduced in 1957 as a sport and racing chronograph following on from the early chronographs of the 1920s and 1930s, including the Omega 28.9 chronograph, which was Omega's first small wrist chronograph, complementing Omega's position as the official timekeeper for the Olympic Games.[6][7] The first Speedmaster model, the reference CK 2915, was powered by the Omega Calibre 321. This movement was developed in 1946 by Albert Piguet of Lemania, which had been acquired in 1932 by Omega's parent company, SSIH. The "Speedmaster" name was coined from the model's novel tachymeter scale bezel (in brushed stainless steel) and by the convention set by prior Omega brands Seamaster and Railmaster.[6] The model established the series's hallmark 12-hour, triple-register chronograph layout, domed Plexiglas crystal (named hésalite), and simple, high-contrast index markers; but, unlike most subsequent Speedmaster models, it used Omega's broad arrow hand set. In 1959, a second version, CK 2998, was released with a black aluminum base 1000 bezel and later in 2998-2, tachymeter 500 bezel and alpha hands. This was again updated in 1963 by references ST 105.002, which kept the alpha hands and then less than one year later ST 105.003 with straight baton hands and ST 105.012, the first Speedmaster with the "Professional" appellation on the dial, with an asymmetrical case to protect the chronograph pushers and crown. All of the early Speedmasters used the same calibre 321 movement, which was only replaced in 1968/69 with the introduction of the calibre 861, which was used in the 'moonwatch'. The watches used for Apollo 11's mission were the 1967 "pre-moon" 321 versions.

Pilots

Chronographs were first developed for use in artillery for battle but soon came to be indispensable for use in high performance machinery, specifically by pilots but later by race car drivers.[8][9][10][11] Submariners, who also relied heavily on split second timing for what was essentially blind travel, were known for the use of chronographs. The ability to clock, and therefore calibrate, fuel consumption, trajectory and other variables allowed for both more efficient travel as well as better pilots and race car drivers. When President Eisenhower decreed that test pilots would be the only permissible option for Project Mercury, the inclusion of a chronograph of some sort was virtually assured.[12]

Use in space

Qualification tests

Three years before the Speedmaster's official qualification for space flight, astronaut Wally Schirra took his personal CK 2998 aboard Mercury-Atlas 8 (Sigma 7) on October 3, 1962.[13] That same year, per an anecdote repeated by Omega press materials, trade publications, and NASA itself, a number of commercial chronograph wristwatches were furtively purchased from Corrigan's, a Houston jeweler, to evaluate their use for the Gemini and Apollo Programs.[6][13][14] James Ragan, a former NASA engineer responsible for Apollo flight hardware testing, has downplayed this story, calling it a "complete invention". Instead, bids were officially solicited of several brands already familiar to the pilots who were joining the growing astronaut corps. Brands under official consideration included Breitling, Rolex, and Omega, as well as others that produced mechanical chronographs.[15][16] Hamilton submitted a pocket watch and was disqualified from consideration, leaving three contenders: Rolex, Longines-Wittnauer, and Omega. These watches were all subjected to tests under extreme conditions:

- High temperature: 48 hours at 160 °F (71 °C) followed by 30 minutes at 200 °F (93 °C)

- Low temperature: Four hours at 0 °F (−18 °C)

- Temperature cycling in near-vacuum: Fifteen cycles of heating to 160 °F (71 °C) for 45 minutes, followed by cooling to 0 °F (−18 °C) for 45 minutes at 10−6 atm

- Humidity: 250 hours at temperatures between 68 °F (20 °C) and 160 °F (71 °C) at relative humidity of 95%

- Oxygen environment: 100% oxygen at 0.35 atm and 71 °C for 48 hours

- Shock: Six 11ms 40 g shocks from different directions

- Linear acceleration: from 1 to 7.25 g within 333 seconds

- Low pressure: 90 minutes at 10−6 atm at 160 °F (71 °C) followed by 30 minutes at 200 °F (93 °C)

- High pressure: 1.6 atm for one hour

- Vibration: three cycles of 30 minutes vibration varying from 5 to 2000 Hz with minimum 8.8 g impulse

- Acoustic noise: 30 minutes at 130 dB from 40 to 10,000 Hz[6][14]

All chronographs tested were mechanical hand-wound models. Neither the first automatic chronograph nor the first quartz watch would be available until 1969, well after the space program was underway. The evaluation concluded in March 1965 with the selection of the Speedmaster, which survived the tests while remaining largely within 5 seconds per day rate.[6][13][15][17]

Gemini program

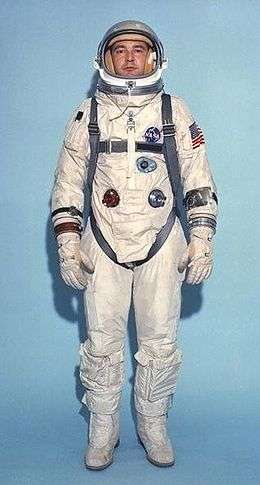

Gus Grissom and John Young wore the first officially qualified Speedmasters on Gemini 3 on March 23, 1965. Several months later, Ed White made the first American space walk during Gemini 4 with a Speedmaster 105.003 strapped to the outside of the left-side sleeve of his G4C space suit.[13] In order to accommodate the space suit, the watch was attached via a long nylon strap secured with Velcro. When worn on the wrist, the strap could be wound around several times to shorten its length.[13] According to Omega, the company was surprised to learn of the Speedmaster’s role upon seeing a photograph of the EVA; however, ordering forms sent by NASA's Gemini 4 Flight Support Procurement Office to Omega's American agents in 1964 suggest that this anecdote may be exaggerated.[6] These images would be widely used in Omega marketing materials from 1965–67, establishing the popular connection between the Speedmaster and space exploration.[6][18] Speedmasters were issued to all subsequent Gemini crews until the end of the program in 1966.

Apollo program

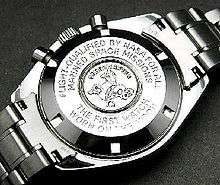

In 1966, Speedmaster reference 105.012 was updated to reference 145.012. These two models would be the two Speedmaster references known to have been worn on the moon by Apollo astronauts, the original "moonwatches."[13] Speedmasters were used throughout the early manned Apollo program, and reached the moon with Apollo 11. Ironically, these and prior models are informally known as "Pre-moon" Speedmasters, since their manufacture predate the moon landings and lack the inscription subsequent models carry: "The First Watch Worn on the Moon".

Although Apollo 11 commander Neil Armstrong was first to set foot on the moon, he left his 105.012 Speedmaster inside the Lunar Module as a backup because the LM's electronic timer had malfunctioned.[19] Buzz Aldrin elected to wear his and so his Speedmaster became the first watch to be worn on the moon. Later, he wrote of his decision:

It was optional to wear while we were walking on the surface of the moon... few things are less necessary when walking around on the moon than knowing what time it is in Houston, Texas. Nonetheless, being a watch guy, I decided to strap the Speedmaster onto my right wrist around the outside of my bulky spacesuit.[19]

Aldrin’s Speedmaster was lost during shipping when he sent it to the Smithsonian Institution, its reference number being ST105.012,[20] although it is sometimes erroneously reported as a 145.012.

In 1970, after Apollo 13 was crippled by the rupture of a Service Module oxygen tank, Jack Swigert's Speedmaster was famously used to accurately time the critical 14-second Mid-Course Correction 5[21] burn using the Lunar Module's Reaction Control System, which allowed for the crew's safe return.[22][23] In recognition of this, Omega was awarded the Snoopy Award by the Apollo 13 astronauts, "for dedication, professionalism, and outstanding contributions in support of the first United States Manned Lunar Landing Project."[24][25]

In 1971, Apollo 15 commander David Scott’s issued Speedmaster lost its Plexiglas crystal during EVA-2. For EVA-3, the final lunar surface EVA, he wore a Bulova Chronograph (model number 88510/01 with velcro-strap part number SEB12100030-202[26]) that was not part of the normal mission equipment and that he had agreed to evaluate for the company at the request of a friend.[27][28] Because of the commercial interests involved and the revelation of the Apollo 15 postage stamp incident, NASA withheld Bulova's name for years afterward. There is also evidence that Rolex GMTs were used as back-up personal watches on the Apollo 13 & 14 missions.[29] Therefore, while the Speedmaster was the first watch worn on the moon, it is not the only one, as Omega often claims on its watches and in marketing materials.

In addition to issued crew watches, Apollo 17 carried an additional Speedmaster to lunar orbit as part of the Heat Flow and Convection Experiment conducted by Command Module pilot Ronald Evans.[30][31] This watch was sold for $23,000 at a Heritage Auction in 2009.[32]

Later models

In 1968, American insurance salesman Ralph Plaisted and three companions were the first confirmed expedition to reach the north pole by land on snowmobiles. The team successfully used the same reference 145.012 Omega Speedmasters as the Apollo program along with sextants for navigation.[33]

Also in 1968, Omega transitioned the caliber 321 movement to the new caliber 861, also designed by Albert Piguet, with the introduction of the reference 145.022 Speedmaster. The 861 was very similar to the 321, but replaced its column wheel switching mechanism with a cam and increased the beat rate from 18 000 to 21 600 vibrations per hour. Most Speedmaster Professional watches from 1968 to the present have used variants of this movement, including the modern rhodium-plated caliber 1861 and decorated exhibition calibers 863 and 1863. A standard Speedmaster Professional model with Plexiglas crystal, solid caseback with anti-vibration and anti-magnetic dust cover, tachymeter scale, without date or day complications, and powered by a caliber 861-based movement has been continuously produced since. The tritium-powered phosphorescent lume on the hands and index markers of the original watches were replaced at the end of the 1990s with non-radioactive pigments (Luminova®), but the fundamental design, dimensions, and mechanism of these watches have remained unchanged. In this form, the basic Speedmaster line has remained flight-qualified for NASA space missions and EVAs, after re-evaluation by NASA in 1972 and for use in the Space Shuttle program in 1978.[34] The current such model is reference 311.30.42.30.01.005 (since 2014).[35]

Omega has produced a large number of commemorative and limited edition variants of the basic "moonwatch" design, celebrating important anniversaries and events, emblazoned with the different patches for the space missions it was issued for, or evoking its motor sport roots with various racing patterns. It has also released many models made with various precious metals, jewels, and alternative dial colors for the luxury market.[36]

Over the years, Omega has also sought to improve functional aspects of the basic Speedmaster Professional. In 1969, it produced the Speedmaster Professional Mk II, with shrouded lugs and a flat, anti-reflective mineral glass crystal. In 1970, Omega launched the Alaska Project under Pierre Chopard, which changed the dial of the original Speedmaster Professional from black to white and created a removable anodized aluminum housing to shield the watch from a wider range of temperatures.[37] In 1971 and 1973, Omega turned to automatic mechanisms the Speedmaster Automatic MkIII and MkIV models alongside Speedsonic Electronic Chronometer Chronograph (marketing as a Speedmaster) other non Speedmaster Chronographs such as the Omega Bullhead. However none of these proved as popular or long-lasting as the basic Speedmaster Professional "moonwatch". A variety of other types of watches have used the Speedmaster brand, including many different automatic day and day-date models, the tuning fork movement Speedsonic line, and the digital LCD Speedmaster Quartz (the Speedsonic and LCD Speedmaster where also prototyped in 10 examples each under the Alaska project but not taken up by NASA). The digital-analog Speedmaster X-33 was produced in 1998; it was qualified for space missions by NASA and flown on the Mir space station and Space Shuttle Columbia during STS-90 later that year.

Gallery

-

Speedmaster worn over a Gemini space suit.

-

Wally Schirra wears his Speedmaster on a pre-flight watchband (Apollo 7)

-

Buzz Aldrin wearing an Omega Speedmaster on the moon (Apollo 11)

-

Alan Bean wearing an Omega Speedmaster (Apollo 12)

-

The prime crew of Apollo 14 wearing Speedmasters prior to launch

See also

References

- ↑ NELSON, A. A. (1993). "The moon watch: a history of the Omega Speedmaster Professional". Bulletin of the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors 35 (282): 33–38.

- ↑ Aldrin, Buzz. Magnificent Desolation. pp. 260–61. ISBN 978-0-307-46346-3.

- ↑ "Omega Watches: Speedmaster History". Omega. Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- ↑ "Omega Watches: Speedmaster". Omega S.A. Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- ↑ Richon 2007, pp. 616, 638–39.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Richon 2007, pp. 596–602

- ↑ Kessler, Ken (2009). "Space Age". Omega Lifetime 4: 30–36.

- ↑ Doggett, Rachel; Jaskot, Susan; Rand, Robert; Bedini, Silvio A; Quinones, Ricardo J (1986), Time: the Greatest Innovator: Timekeeping and Time Consciousness in Early Modern Europe, Washington, D.C.: Folger Shakespeare Library.

- ↑ Hood, Peter (1969), How Time Is Measured, London: Oxford UP.

- ↑ Cowan, Harrison J (1958), Time and Its Measurement; from the Stone Age to the Nuclear Age, Cleveland: World Pub..

- ↑ Chronographs, IT: Spencer Emergency Solutions, retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ↑ Shapira, J.A. "The Chronograph – Watch Complications Explained". Gentlemans’ Gazette. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Apollo Lunar Surface Journal: Omega Speedmaster Professional Chronographs". NASA. Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- 1 2 "How the Omega Speedmaster became the Moonwatch" (press release). Omega. 6 April 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- 1 2 "James H. Ragan: NASA's man behind the MoonWatch" (press release). Omega. 21 July 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ↑ Linz & Ragan 2009, pp. 124–25

- ↑ Linz & Ragan 2009, pp. 124–25

- ↑ "Omega Watches: Advertisement". Hall of fame. Omega. Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- 1 2 Aldrin, Buzz (1973). Return To Earth. Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-48832-5.

- ↑ According to Omega Museum, as reported in How Omega Speedmaster became MoonWatch, Monochrome watches.

- ↑ NTRS (PDF), Nasa.

- ↑ Mission Operations Report: Apollo 13 (PDF) (NASA-MSC Internal Report), NASA, 1970-04-28, pp. 10–2

- ↑ Woodfill, Jerry (2010-04-16). "13 Things That Saved Apollo 13, Part 6: Navigating By the Earth's Terminator". Universe Today. Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- ↑ "Omega and Snoopy: Two Great Names in the History of Space Exploration". Omega. 2003-04-03. Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- ↑ Richon 2007, p. 607.

- ↑ "Band specs current", Omega velcro blueprints (JPEG), Chrono Maddox.

- ↑ "Apollo 15 Lunar Surface Journal: Preparations for EVA-2". NASA. 2008-11-22. Retrieved 2011-02-10.

- ↑ Mission Operations Report: Apollo 13 (news release), NASA, 1972-09-15, 72-189

- ↑ "Apollo 14 Rolex GMT". UK: Rolex blog. Jun 2008. Retrieved 2014-12-16.

- ↑ "Experiment: Heat Flow and Convection". NASA. Retrieved 2011-02-10.

- ↑ Apollo 17 Heat Flow and Convection Experiments (PDF) (Technical Memorandum), NASA, 1973-07-16, TM-X 64772

- ↑ "Apollo 17 Flown Omega Stainless Steel Speedmaster Professional Watch". Heritage Auctions. Retrieved 2011-02-09.

- ↑ Richon 2007, p. 603.

- ↑ Richon 2007, pp. 607, 614.

- ↑ "Speedmaster Moon Watch Profession", Collection, Omega.

- ↑ Richon 2007, pp. 598–670.

- ↑ "An Interview with Pierre Chopard, Leader of the Omega Speedmaster Alaska Project". Hodnikee. 2011-01-27. Retrieved 2011-02-09.

Bibliography

- Linz, Alexander; Ragan, James H (June 2009), "How Omega Got to the Moon", Watch Time: 124–25.

- Richon, Marco (2007), A Journey Through Time, Omega, ISBN 978-2-9700562-2-5.

External links

- History of the Omega Speedmaster, Chrono Maddox, a detailed table of Speedmaster models

- Iconic Watches: Omega Speedmaster Professional, Time & Watches.

- Omega Speedmaster Professional Chronographs, NASA History page.

- speedmaster-mission.net, by Jean-Michel

- NASA blueprint SEB12100030 for velcro watchbands (sheet 1 of 2) Material specifications, notes and revisions.

- NASA blueprint SEB12100030 for velcro watchbands (sheet 2 of 2) Assembly diagrams.

- Omega

- The Right Stuff: Inside the Omega Speedmaster Professional - Part 1, by Jack Forster

- The Right Stuff: Inside the Omega Speedmaster Professional - Part 2, by Jack Forster

- Legendary Watches: The Omega Speedmaster, by Matthew Boston

- Legend of The Moon Watch: Omega Speedmaster

- The truth about the real Armstrong’s and Aldrin’s Speedmaster references and how the Omega Speedmaster became the Moonwatch by Monochrome-Watches

- The history of the Omega Speedmaster - Part 1, the early Pre-Moons by Monochrome-Watches