Omaha-class cruiser

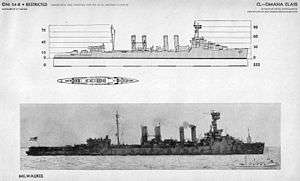

.jpg) USS Milwaukee (CL-5), an Omaha-class cruiser. | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Omaha class |

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | Chester class |

| Succeeded by: | Brooklyn class |

| In commission: | 1923 - 1946 |

| Planned: | 10 |

| Completed: | 10 |

| Scrapped: | 10 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Light cruiser |

| Displacement: | 7,050 long tons (7,160 t) |

| Length: | 556 ft 6 in (169.62 m) |

| Beam: | 55 ft 4 in (16.87 m) |

| Draft: | 20 ft 0 in (6.10 m) |

| Installed power: | 90,000 shp (67,000 kW) |

| Propulsion: | 12 Yarrow boilers (265 psi (1,830 kPa)) |

| Speed: | 35 knots (65 km/h) |

| Endurance: | 9,000 nautical miles (17,000 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h) |

| Complement: | 360 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | |

The Omaha-class cruisers were a class of light cruisers built for the United States Navy. The oldest class of cruiser still in service with the Navy at the outbreak of World War II, the Omaha class was an immediate post-World War I design.

History

Maneuvers conducted in January 1915 made it clear that the US Atlantic Fleet lacked the fast cruisers necessary to provide information on the enemy's position and to deny the enemy information of the fleet's own position and to screen friendly forces. Built to scout for a fleet of battleships, the Omaha class featured high speed (35 knots (65 km/h; 40 mph)) for cooperation with destroyers, and 6-inch (152 mm) guns to fend off any destroyers the enemy might send against them. Displacing 7,050 long tons (7,160 t), they were just over 555 feet (169 m) long.

The Omaha class was designed specifically in response to the British Centaur subclass of the C-class cruiser. Although from a modern viewpoint, a conflict between the US and Great Britain seems implausible, US Navy planners during this time and up to the mid-1930s considered Britain to be a formidable rival for power in the Atlantic, and the possibility of armed conflict between the two countries plausible enough to merit appropriate planning measures.

The Omaha class mounted four smokestacks, a look remarkably similar to the Clemson-class destroyers (a camouflage scheme was devised to enhance the resemblance). Their armament showed the slow change from casemate-mounted weapons to turret-mounted guns. They held a full twelve 6-inch/53 caliber guns, of which four were mounted in two twin turrets, one fore and one aft, and the remaining eight in casemates; four on each side. Launched in 1920, Omaha (designated C-4 and later CL-4) had a displacement of 7,050 long tons. The cruisers emerged with a distinctly old-fashioned appearance owing to their World War I-type stacked twin casemate-mount cannons and were among the last broadside cruisers designed anywhere.

As a result of the design changes placed on the ship mid-construction, the Omaha that entered the water in 1920 was a badly overloaded design that, even at the beginning, had been rather tight. The ships were insufficiently insulated, too hot in the tropics and too cold in the north. Sacrifices in weight savings in the name of increased speed led to severe compromise in the habitability of the ship. While described as a good ship in a seaway, the low freeboard led to frequent water ingestion over the bow and in the torpedo compartments and lower aft casements. The lightly built hulls leaked, so that sustained high-speed steaming contaminated the oil tanks with sea water.

These drawbacks notwithstanding, the US Navy took some pride in the Omaha class. They featured improved compartmentalization; propulsion machinery was laid out on the unit system, with alternating groups of boiler rooms and engine rooms, to prevent immobilization by a single torpedo hit. Magazines were the first to be placed on centerline, below the waterline. A serious flaw in these ships' subdivision was the complete lack of watertight bulkheads anywhere above the main deck or aft on the main deck.

Originally designed to serve as a scout, they served throughout the interwar period as leaders of fleet flotillas, helping them resist enemy destroyer attack. Tactical scouting became the province of cruiser aircraft, and the distant scouting role was taken over by the new heavy cruisers spawned by the Washington Naval Treaty. Thus, the Omaha class never performed their designed function. They were relegated to the fleet-screening role, where their high speed and great volume of fire were most appreciated.

Due to the large topweight lasting on these ships, compounded by the high-mounted catapults, the Navy removed the two lower aft firing casemate-mounted 6-inch guns in 1939, fairing over the casemates port and starboard.

These were the oldest class of cruisers still in service with the Navy in 1941. All were modified during the war with additional 20mm and 40mm anti aircraft guns and radar.

Both Detroit and Raleigh were at Pearl Harbor during the attack, with Raleigh being torpedoed. Detroit and USS Phoenix were the only large ships to get out of the harbor during the attack.

The ships of the Omaha class spent most of the war deployed to secondary theaters and in less vital tasks than those assigned to more recently built cruisers. The Omaha class were sent in places where their significant armament might be useful if called upon, but where their age and limited abilities were less likely to be tested. These secondary destinations included patrols off the East and West coasts of South America, convoy escort in the South Pacific far from the front lines of battle, patrols and shore bombardment along the distant and frigid Aleutians and Kuril Islands chains, and bombardment duty in the invasion of Southern France when naval resistance was expected to be minimal. The most significant action that any of the ships of the class saw during the war was Marblehead's participation in early war actions around the Dutch East Indies (most notably, the Battle of Makassar Strait), and Richmond's engagement in the Battle of the Komandorski Islands.

None of the ships were wartime losses. Raleigh's torpedo damage at Pearl Harbor and Marblehead's damage at Makassar Straight were the only significant wartime combat damage suffered by the class.

The ships of the class were considered obsolete as the war ended, and were decommissioned and scrapped within seven months of the surrender of Japan (with the exception of Milwaukee, which had been loaned to the Soviet Navy, and was scrapped when returned to US Navy control in 1949).

Ships of the class

The following ships of the class were constructed.[1]

- USS Omaha (CL-4) - Commissioned 24 Feb 1923

- USS Milwaukee (CL-5) - Commissioned 20 Jun 1923

- USS Cincinnati (CL-6) - Commissioned 1 Jan 1924

- USS Raleigh (CL-7) - Commissioned 6 Feb 1924

- USS Detroit (CL-8) - Commissioned 31 Jul 1923

- USS Richmond (CL-9) - Commissioned 2 Jul 1923

- USS Concord (CL-10) - Commissioned 3 Nov 1923

- USS Trenton (CL-11) - Commissioned 19 Apr 1924

- USS Marblehead (CL-12) - Commissioned 8 Sep 1924

- USS Memphis (CL-13) - Commissioned 4 Feb 1925

Omaha alternatives

The U.S. Navy was not entirely pleased with the Omaha class, so a new design was drawn up that was derived from it. This new class replaced the 6-inch guns with four turrets (2 forward, 2 aft) each with two 6-inch guns.

Two other Omaha versions were also designed. The first, intended to function as a monitor, had two 14-inch guns in 2 single turrets, while the other design had four 8-inch guns in two twin turrets. The second design eventually evolved into the Pensacola-class cruiser.

References

- ↑ "U.S. Navy Cruisers 1940-1945". Retrieved 18 September 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Omaha class cruiser. |

- http://www.avalanchepress.com/OmahaAlternatives.php

- http://www.avalanchepress.com/AmericanCruisers.php

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||