Sea of Okhotsk

| Sea of Okhotsk | |

|---|---|

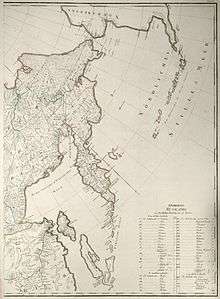

Map of the Sea of Okhotsk | |

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 55°N 150°E / 55°N 150°ECoordinates: 55°N 150°E / 55°N 150°E |

| Type | Sea |

| Basin countries | Japan, Russia |

| Surface area | 1,583,000 km2 (611,200 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 859 m (2,818 ft) |

| Max. depth | 3,372 m (11,063 ft) |

The Sea of Okhotsk (Russian: Охо́тское мо́ре, tr. Okhotskoye More; IPA: [ɐˈxotskəɪ ˈmorʲɪ]; Japanese: オホーツク海 Ohōtsuku-kai) is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean,[1] lying between the Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands on the southeast, the island of Hokkaido to the south, the island of Sakhalin along the west, and a long stretch of eastern Siberian coast (including the Shantar Islands) along the west and north. The northeast corner is the Shelikhov Gulf. The sea is named after Okhotsk, the first Russian settlement in the Far East.

Geography

The Sea of Okhotsk covers an area of 1,583,000 square kilometres (611,000 sq mi), with a mean depth of 859 metres (2,818 ft) and a maximum depth of 3,372 metres (11,063 ft). It is connected to the Sea of Japan on either side of Sakhalin: on the west through the Sakhalin Gulf and the Gulf of Tartary; on the south, through the La Pérouse Strait.

In winter, navigation on the Sea of Okhotsk becomes difficult, or even impossible, due to the formation of large ice floes, because the large amount of freshwater from the Amur River lowers the salinity which results in raising the freezing point of the sea. The distribution and thickness of ice floes depends on many factors: the location, the time of year, water currents, and the sea temperatures.

With the exception of Hokkaido, one of the Japanese home islands, the sea is surrounded on all sides by territory administered by the Russian Federation.

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the Sea of Okhotsk as follows:[2]

- On the Southwest. The Northeastern and Northern limits on the Japan Sea [In La Perouse Strait (Sôya Kaikyô). A line joining Sôni Misaki and Nishi Notoro Misaki (45°55'N). From Cape Tuik (51°45'N) to Cape Sushcheva].

- On the Southeast. A line running from Nosyappu Saki (Cape Noshap, 43°23'N) in the Island of Hokusyû (Yezo) through the Kuril or Tisima Islands to Cape Lopatka (South point of Kamchatka) in such a way that all the narrow waters between Hokusyû and Kamchatka are included in the Sea of Okhotsk.

Islands

Some of the Sea of Okhotsk's islands are quite large, including Japan's second largest island, Hokkaido, as well as Russia's largest island, Sakhalin. Practically all of the sea's islands are either in coastal waters or belong to the various islands making up the Kuril Islands chain. These fall either under undisputed Japanese or Russian ownership or disputed ownership between Japan and Russia. Iony Island is the only island located in open waters and belongs to the Khabarovsk Krai of the Russian Federation. The majority of the sea's islands are uninhabited making them ideal breeding grounds for seals, sea lions, seabirds, and other sea island fauna. Large colonies, with over a million individuals, of crested auklets use the Sea of Okhotsk as a nesting site.

History

Russian explorers Ivan Moskvitin and Vassili Poyarkov were the first Europeans to visit the Sea of Okhotsk (and, probably, the island of Sakhalin[3]) in the 1640s. The Dutch captain Maarten Gerritsz Vries in the Breskens entered the Sea of Okhotsk from the south-east in 1643, and charted parts of the Sakhalin coast and Kurile Islands, but failed to realize that either Sakhalin or Hokkaido are islands.

The first and foremost Russian settlement on the shore was the port of Okhotsk, which relinquished commercial supremacy to Ayan in the 1840s. The Russian-American Company all but monopolized the commercial navigation of the sea in the first half of the 19th century.

The Second Kamchatka Expedition under Vitus Bering systematically mapped the entire coast of the sea, starting in 1733. Jean-François de La Pérouse and William Robert Broughton were the first non-Russian European navigators known to have passed through these waters other than Maarten Gerritsz Vries. Ivan Krusenstern explored the eastern coast of Sakhalin in 1805. Mamiya Rinzō and Gennady Nevelskoy determined that the Sakhalin was indeed an island separated from the mainland by a narrow strait. The first detailed summary of the hydrology of the Okhotsk sea was prepared and published by Stepan Makarov in 1894.

During the Cold War, the Sea of Okhotsk was the scene of several successful U.S. Navy operations (including Operation Ivy Bells) to tap Soviet Navy undersea communications cables. These operations were documented in the book Blind Man's Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage. The sea (and surrounding area) were also the scene of the Soviet PVO Strany attack on Korean Air Flight 007 in 1983. The Soviet Pacific Fleet used the Sea as a ballistic missile submarine bastion,[4] a strategy that Russia continues.

In the Japanese language, the sea has no traditional Japanese name despite its close location to the Japanese territories and is called Ohōtsuku-kai (オホーツク海), which is a transcription of the Russian name. Additionally, Okhotsk Subprefecture, Hokkaidō which faces the sea, also known as Okhotsk region (オホーツク地方 Ohōtsuku-chihō), is named after the sea.

The Sea of Okhotsk was a hotbed for whaling in the middle of the 19th century. Beginning in 1845, American whaleships began hunting right whales in the southeastern part of the Sea of Okhotsk near the Kurile Islands. The first bowheads were caught in 1847. From 1849 bowheads dominated the catch. Between 1850 and 1853 the majority of the fleet focused their efforts on bowheads in the Bering Strait region. Following poor catches there, whaleships began shifting their attention to the stock of bowhead whales in the Sea of Okhotsk. In 1854 alone some 160 vessels visited the region. Next year more than 130 ships. The next year, in 1856, nearly 150 ships sailed to the Okhotsk. By 1857, the number of ships had declined to a little over 100. With declining catches from 1858 to 1860, the fleet shifted its focus back to the Bering Strait region.[5] Many of the ships converged on the Shantar Islands, anchoring within the archipelago's many sheltered bays. On July 28, 1854 the New Bedford ship Isabella reported 94 ships in sight from her deck. A few days later, the Lexington of Nantucket reported one hundred whaleboats were about chasing whales.

Even here the effects of the American Civil War were felt. In late May 1865, the Confederate States Navy Steamer Shenandoah sailed into the Sea of Okhotsk to hunt Union whaling ships. The CSS Shenandoah was a commerce raider, whose mission was to destroy Union merchant shipping and thus draw off United States Navy ships in pursuit and thereby loosen the US Navy blockade of Confederate coasts. The ship spent more than three weeks here, but because of the dangerous ice, only destroyed one Union whaler. It then moved on to the North Pacific where it virtually destroyed the U.S. North Pacific whaling fleet, capturing 24 ships and sinking almost all of them.

Ships continued to hunt whales in the Sea of Okhotsk until the early 20th century.

Oil and gas exploration

29 zones of possible oil and gas accumulation have been identified on the Sea of Okhotsk shelf, which runs along the coast. Total reserves are estimated at 3.5 billion tons of equivalent fuel, including 1.2 billion tons of oil and 1.5 billion cubic meters of gas.[6]

On 18 December 2011 the Russian oil drilling rig Kolskaya[7] capsized and sank in a storm in the Sea of Okhotsk, some 124 km from Sakhalin Island, where it was being towed from Kamchatka. Reportedly its pumps failed, causing it to take on water and sink. The platform carried 67 people, of which 14 were initially rescued by the icebreaker Magadan and the tugboat Natftogaz-55. The platform was subcontracted to a company working for the Russian energy giant Gazprom.[8][9][10]

Notable seaports

- Magadan, Magadan, Russia - population: 95,000

- Palana, Kamchatka, Russia - population: 3,000

- Abashiri, Hokkaido, Japan - population: 38,000

- Monbetsu, Hokkaido, Japan - population: 25,000

- Wakkanai, Hokkaido, Japan - population: 38,000

See also

References

- ↑ Kon-Kee Liu; Larry Atkinson (June 2009). Carbon and Nutrient Fluxes in Continental Margins: A Global Synthesis. Springer. pp. 331–333. ISBN 978-3-540-92734-1. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- ↑ "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ↑ Stephan, John J. (1971), Sakhalin: a history, Clarendon Press, p. 11

- ↑ Acharya, Amitav (March 1988). "The United States Versus the USSR in the Pacific: Trends in the Military Balance". Contemporary Southeast Asia (Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) 9 (4): 293. ISSN 1793-284X – via JSTOR. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Bockstoce, John (1986). Whales, Ice, & Men: The History of Whaling in the Western Arctic. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97447-8.

- ↑ "Magadan Region". Kommersant, Russia's Daily Online. Retrieved January 22, 2007.

- ↑ Technical details of the rig can be found here : http://www.rigzone.com/data/rig_detail.asp?rig_id=521 and here: http://www.amngr.ru/index.php/en/services/fleet/kolskaya

- ↑ "Russian oil rig sinks, leaving many missing". CNN. December 18, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- ↑ "Kolskaya Sinks Offshore Russia". Rigzone. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ↑ "Blog Archive » Rig Kolskaya Lost". Shipwreck Log. December 18, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

.jpeg)