Nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions that release nuclear energy[5] to generate heat, which most frequently is then used in steam turbines to produce electricity in a nuclear power station. The term includes nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion. Presently, the nuclear fission of elements in the actinide series of the periodic table produce the vast majority of nuclear energy in the direct service of humankind, with nuclear decay processes, primarily in the form of geothermal energy, and radioisotope thermoelectric generators, in niche uses making up the rest.

Nuclear (fission) power stations, excluding the contribution from naval nuclear fission reactors, provided 11% of the world's electricity in 2012,[6] somewhat less than that generated by hydro-electric stations at 16%. Since electricity accounts for about 25% of humanity's energy usage with the majority of the rest coming from fossil fuel reliant sectors such as transport, manufacture and home heating, nuclear fission's contribution to the global final energy consumption is about 2.5%,[7] a little more than the combined global electricity production from "new renewables"; wind, solar, biofuel and geothermal power, which together provided 2% of global final energy consumption in 2014.[8]

Regional differences in the use of fission energy are large. Fission energy generation, with a 20% share of the U.S. electricity production, is the single largest deployed technology among current low-carbon power sources in the country.[9] In addition, two-thirds of the European Union's twenty-seven nations's low-carbon energy is produced by fission.[10] Some of these nations have banned its generation, such as Italy, which ended the use of fission-electric generation, which started in 1963, in 1990. France is the largest user of nuclear energy, deriving 75% of its electricity from fission.

Along with other sustainable energy sources, nuclear fission power is a low carbon power generation method of producing electricity, meaning that it is in the renewable energy family of low associated greenhouse gas emissions per unit of energy generated.[11] As all electricity supplying technologies use cement etc., during construction, emissions are yet to be brought to zero. A 2014 analysis of the carbon footprint literature by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reported that fission electricities embodied total life-cycle emission intensity value of 12 g CO2 eq/kWh is the lowest out of all commercial baseload energy sources,[12][13] and second lowest out of all commercial electricity technologies known, after wind power which is an Intermittent energy source with embodied greenhouse gas emissions, per unit of energy generated of 11 g CO2eq/kWh. Each result is contrasted with coal & fossil gas at 820 and 490 g CO2 eq/kWh.[12][13] With this translating into, from the beginning of Fission-electric power station commercialization in the 1970s, having prevented the emission of about 64 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, greenhouse gases that would have otherwise resulted from the burning of fossil fuels in thermal power stations.[14]

In 2013, the IAEA reported that there are 437 operational civil fission-electric reactors[15] in 31 countries,[16] although not every reactor is producing electricity.[17] In addition, there are approximately 140 naval vessels using nuclear propulsion in operation, powered by some 180 reactors.[18][19][20] As of 2013, attaining a net energy gain from sustained nuclear fusion reactions, excluding natural fusion power sources such as the Sun, remains an ongoing area of international physics and engineering research. With commercial fusion power production remaining unlikely before 2050.[21]

In 2015, the IAEA report that worldwide there were 67 civil fission-electric power reactors under construction in 15 countries including Gulf states such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE).[15] Over half of the 67 total being built are in Asia, with 28 in the Peoples Republic of China (PRC), with the most recently completed fission-electric reactor to be connected to the electrical grid, as of August 2015, occurring in Wolseong Nuclear Power Plant in the Republic of Korea.[22] Five other new grid connections were completed by the PRC so far this year.[23] In the US, four new Generation III reactors are under construction at Vogtle and Summer station, while a fifth is nearing completion at Watts Bar station, all five are expected to enter service before 2020.[24] In 2013, four aging uncompetitive U.S reactors were closed.[25][26] According to the World Nuclear Association, the global trend is for new nuclear power stations coming online to be balanced by the number of old plants being retired.[27]

There is a social debate about nuclear power.[28][29][30] Proponents, such as the World Nuclear Association and Environmentalists for Nuclear Energy, contend that nuclear power is a safe, sustainable energy source that reduces carbon emissions.[31] Opponents, such as Greenpeace International and NIRS, contend that nuclear power poses many threats to people and the environment.[32][33][34]

Far reaching fission power reactor accidents, or accidents that resulted in medium to long-lived fission product contamination of inhabited areas, have occurred in Generation I & II reactor designs, blueprinted between 1950 and 1980. These include the Chernobyl disaster which occurred in 1986, the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster (2011), and the more contained Three Mile Island accident (1979).[35] There have also been some nuclear submarine accidents.[35][36][37] In terms of lives lost per unit of energy generated, analysis has determined that fission-electric reactors have caused less fatalities per unit of energy generated than the other major sources of energy generation. Energy production from coal, petroleum, natural gas and hydroelectricity has caused a greater number of fatalities per unit of energy generated due to air pollution and energy accident effects.[38][39][40][41][42] However, the economic costs of nuclear power accidents is high, and meltdowns can render areas uninhabitable for very long periods. The human costs of evacuations of affected populations and lost livelihoods is also significant.[43][44][45]

Japan's 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, which occurred in a reactor design from the 1960s, prompted a re-examination of nuclear safety and nuclear energy policy in many countries.[46] Germany plans to close all its reactors by 2022, and Italy has re-affirmed its ban on electric utilities generating, but not importing, fission derived electricity.[46] In 2011 the International Energy Agency halved its prior estimate of new generating capacity to be built by 2035.[47][48] In 2013 Japan signed a deal worth $22 billion, in which Mitsubishi Heavy Industries would build four modern Atmea reactors for Turkey.[49] In August 2015, following 4 years of near zero fission-electricity generation, Japan began restarting its fission fleet, after safety upgrades were completed, beginning with Sendai fission-electric station.[50]

Use

In 2011 nuclear power provided 10% of the world's electricity[6] In 2007, the IAEA reported there were 439 nuclear power reactors in operation in the world,[51] operating in 31 countries.[16] In Japan many reactors ceased operation in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear disaster while they are assessed for safety. In 2011 worldwide nuclear output fell by 4.3%, the largest decline on record, on the back of sharp declines in Japan (-44.3%) and Germany (-23.2%).[52]

Since commercial nuclear energy began in the mid-1950s, 2008 was the first year that no new nuclear power plant was connected to the grid, although two were connected in 2009.[53][54]

Annual generation of nuclear power has been on a slight downward trend since 2007, decreasing 1.8% in 2009 to 2558 TWh with nuclear power meeting 13–14% of the world's electricity demand.[55] One factor in the nuclear power percentage decrease since 2007 has been the prolonged shutdown of large reactors at the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Power Plant in Japan following the Niigata-Chuetsu-Oki earthquake.[55]

The United States produces the most nuclear energy, with nuclear power providing 19%[56] of the electricity it consumes, while France produces the highest percentage of its electrical energy from nuclear reactors—80% as of 2006.[57] In the European Union as a whole, nuclear energy provides 30% of the electricity.[58] Nuclear energy policy differs among European Union countries, and some, such as Austria, Estonia, Ireland and Italy, have no active nuclear power stations. In comparison, France has a large number of these plants, with 16 multi-unit stations in current use.

In the US, while the coal and gas electricity industry is projected to be worth $85 billion by 2013, nuclear power generators are forecast to be worth $18 billion.[59]

Many military and some civilian (such as some icebreaker) ships use nuclear marine propulsion, a form of nuclear propulsion.[60] A few space vehicles have been launched using full-fledged nuclear reactors: 33 reactors belong to the Soviet RORSAT series and one was the American SNAP-10A.

International research is continuing into safety improvements such as passively safe plants,[61] the use of nuclear fusion, and additional uses of process heat such as hydrogen production (in support of a hydrogen economy), for desalinating sea water, and for use in district heating systems.

Use in space

Both fission and fusion appear promising for space propulsion applications, generating higher mission velocities with less reaction mass. This is due to the much higher energy density of nuclear reactions: some 7 orders of magnitude (10,000,000 times) more energetic than the chemical reactions which power the current generation of rockets.

Radioactive decay has been used on a relatively small scale (few kW), mostly to power space missions and experiments by using radioisotope thermoelectric generators such as those developed at Idaho National Laboratory.

History

Origins

The pursuit of nuclear energy for electricity generation began soon after the discovery in the early 20th century that radioactive elements, such as radium, released immense amounts of energy, according to the principle of mass–energy equivalence. However, means of harnessing such energy was impractical, because intensely radioactive elements were, by their very nature, short-lived (high energy release is correlated with short half-lives). However, the dream of harnessing "atomic energy" was quite strong, even though it was dismissed by such fathers of nuclear physics like Ernest Rutherford as "moonshine."[62] This situation, however, changed in the late 1930s, with the discovery of nuclear fission.

In 1932, James Chadwick discovered the neutron,[63] which was immediately recognized as a potential tool for nuclear experimentation because of its lack of an electric charge. Experimentation with bombardment of materials with neutrons led Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie to discover induced radioactivity in 1934, which allowed the creation of radium-like elements at much less the price of natural radium.[64] Further work by Enrico Fermi in the 1930s focused on using slow neutrons to increase the effectiveness of induced radioactivity. Experiments bombarding uranium with neutrons led Fermi to believe he had created a new, transuranic element, which was dubbed hesperium.[65]

But in 1938, German chemists Otto Hahn[66] and Fritz Strassmann, along with Austrian physicist Lise Meitner[67] and Meitner's nephew, Otto Robert Frisch,[68] conducted experiments with the products of neutron-bombarded uranium, as a means of further investigating Fermi's claims. They determined that the relatively tiny neutron split the nucleus of the massive uranium atoms into two roughly equal pieces, contradicting Fermi.[65] This was an extremely surprising result: all other forms of nuclear decay involved only small changes to the mass of the nucleus, whereas this process—dubbed "fission" as a reference to biology—involved a complete rupture of the nucleus. Numerous scientists, including Leó Szilárd, who was one of the first, recognized that if fission reactions released additional neutrons, a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction could result. Once this was experimentally confirmed and announced by Frédéric Joliot-Curie in 1939, scientists in many countries (including the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and the Soviet Union) petitioned their governments for support of nuclear fission research, just on the cusp of World War II, for the development of a nuclear weapon.[69]

In the United States, where Fermi and Szilárd had both emigrated, this led to the creation of the first man-made reactor, known as Chicago Pile-1, which achieved criticality on December 2, 1942. This work became part of the Manhattan Project, which made enriched uranium and built large reactors to breed plutonium for use in the first nuclear weapons, which were used on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Unexpectedly high costs in the U.S. nuclear weapons program, along with competition with the Soviet Union and a desire to spread democracy through the world, created "...pressure on federal officials to develop a civilian nuclear power industry that could help justify the government's considerable expenditures."[70] In 1945, the pocketbook The Atomic Age heralded the untapped atomic power in everyday objects and depicted a future where fossil fuels would go unused. One science writer, David Dietz, wrote that instead of filling the gas tank of your car two or three times a week, you will travel for a year on a pellet of atomic energy the size of a vitamin pill. Glenn Seaborg, who chaired the Atomic Energy Commission, wrote "there will be nuclear powered earth-to-moon shuttles, nuclear powered artificial hearts, plutonium heated swimming pools for SCUBA divers, and much more". These overly optimistic predications remain unfulfilled.[71]

United Kingdom, Canada,[72] and USSR proceeded over the course of the late 1940s and early 1950s. Electricity was generated for the first time by a nuclear reactor on December 20, 1951, at the EBR-I experimental station near Arco, Idaho, which initially produced about 100 kW.[73][74] Work was also strongly researched in the US on nuclear marine propulsion, with a test reactor being developed by 1953 (eventually, the USS Nautilus, the first nuclear-powered submarine, would launch in 1955).[75] In 1953, US President Dwight Eisenhower gave his "Atoms for Peace" speech at the United Nations, emphasizing the need to develop "peaceful" uses of nuclear power quickly. This was followed by the 1954 Amendments to the Atomic Energy Act which allowed rapid declassification of U.S. reactor technology and encouraged development by the private sector. This involved a significant learning phase, with many early partial core meltdowns and accidents at experimental reactors and research facilities.[76]

Early years

On June 27, 1954, the USSR's Obninsk Nuclear Power Plant became the world's first nuclear power plant to generate electricity for a power grid, and produced around 5 megawatts of electric power.[77][78]

Later in 1954, Lewis Strauss, then chairman of the United States Atomic Energy Commission (U.S. AEC, forerunner of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the United States Department of Energy) spoke of electricity in the future being "too cheap to meter".[79] Strauss was very likely referring to hydrogen fusion[80] —which was secretly being developed as part of Project Sherwood at the time—but Strauss's statement was interpreted as a promise of very cheap energy from nuclear fission. The U.S. AEC itself had issued far more realistic testimony regarding nuclear fission to the U.S. Congress only months before, projecting that "costs can be brought down... [to]... about the same as the cost of electricity from conventional sources..."[81] Significant disappointment would develop later on, when the new nuclear plants did not provide energy "too cheap to meter."

In 1955 the United Nations' "First Geneva Conference", then the world's largest gathering of scientists and engineers, met to explore the technology. In 1957 EURATOM was launched alongside the European Economic Community (the latter is now the European Union). The same year also saw the launch of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

The world's first commercial nuclear power station, Calder Hall at Windscale, England, was opened in 1956 with an initial capacity of 50 MW (later 200 MW).[82][83] The first commercial nuclear generator to become operational in the United States was the Shippingport Reactor (Pennsylvania, December 1957).

One of the first organizations to develop nuclear power was the U.S. Navy, for the purpose of propelling submarines and aircraft carriers. The first nuclear-powered submarine, USS Nautilus (SSN-571), was put to sea in December 1954.[84] Two U.S. nuclear submarines, USS Scorpion and USS Thresher, have been lost at sea. Eight Soviet and Russian nuclear submarines have been lost at sea. This includes the Soviet submarine K-19 reactor accident in 1961 which resulted in 8 deaths and more than 30 other people were over-exposed to radiation.[36] The Soviet submarine K-27 reactor accident in 1968 resulted in 9 fatalities and 83 other injuries.[37] Moreover, Soviet submarine K-429 sank twice, but was raised after each incident. Several serious nuclear and radiation accidents have involved nuclear submarine mishaps.[35][37]

The U.S. Army also had a nuclear power program, beginning in 1954. The SM-1 Nuclear Power Plant, at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, was the first power reactor in the U.S. to supply electrical energy to a commercial grid (VEPCO), in April 1957, before Shippingport. The SL-1 was a U.S. Army experimental nuclear power reactor at the National Reactor Testing Station in eastern Idaho. It underwent a steam explosion and meltdown in January 1961, which killed its three operators.[85] In Soviet Union in The Mayak Production Association there were a number of accidents including an explosion that released 50-100 tonnes of high-level radioactive waste, contaminating a huge territory in the eastern Urals and causing numerous deaths and injuries. The Soviet regime kept this accident secret for about 30 years. The event was eventually rated at 6 on the seven-level INES scale (third in severity only to the disasters at Chernobyl and Fukushima).

Development

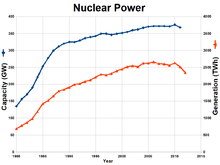

(click image for legend)

Installed nuclear capacity initially rose relatively quickly, rising from less than 1 gigawatt (GW) in 1960 to 100 GW in the late 1970s, and 300 GW in the late 1980s. Since the late 1980s worldwide capacity has risen much more slowly, reaching 366 GW in 2005. Between around 1970 and 1990, more than 50 GW of capacity was under construction (peaking at over 150 GW in the late 1970s and early 1980s) — in 2005, around 25 GW of new capacity was planned. More than two-thirds of all nuclear plants ordered after January 1970 were eventually cancelled.[84] A total of 63 nuclear units were canceled in the USA between 1975 and 1980.[86]

During the 1970s and 1980s rising economic costs (related to extended construction times largely due to regulatory changes and pressure-group litigation)[87] and falling fossil fuel prices made nuclear power plants then under construction less attractive. In the 1980s (U.S.) and 1990s (Europe), flat load growth and electricity liberalization also made the addition of large new baseload capacity unattractive.

The 1973 oil crisis had a significant effect on countries, such as France and Japan, which had relied more heavily on oil for electric generation (39%[88] and 73% respectively) to invest in nuclear power.[89]

Some local opposition to nuclear power emerged in the early 1960s,[90] and in the late 1960s some members of the scientific community began to express their concerns.[91] These concerns related to nuclear accidents, nuclear proliferation, high cost of nuclear power plants, nuclear terrorism and radioactive waste disposal.[92] In the early 1970s, there were large protests about a proposed nuclear power plant in Wyhl, Germany. The project was cancelled in 1975 and anti-nuclear success at Wyhl inspired opposition to nuclear power in other parts of Europe and North America.[93][94] By the mid-1970s anti-nuclear activism had moved beyond local protests and politics to gain a wider appeal and influence, and nuclear power became an issue of major public protest.[95] Although it lacked a single co-ordinating organization, and did not have uniform goals, the movement's efforts gained a great deal of attention.[96] In some countries, the nuclear power conflict "reached an intensity unprecedented in the history of technology controversies".[97]

In France, between 1975 and 1977, some 175,000 people protested against nuclear power in ten demonstrations.[98] In West Germany, between February 1975 and April 1979, some 280,000 people were involved in seven demonstrations at nuclear sites. Several site occupations were also attempted. In the aftermath of the Three Mile Island accident in 1979, some 120,000 people attended a demonstration against nuclear power in Bonn.[98] In May 1979, an estimated 70,000 people, including then governor of California Jerry Brown, attended a march and rally against nuclear power in Washington, D.C.[99] Anti-nuclear power groups emerged in every country that has had a nuclear power programme. Some of these anti-nuclear power organisations are reported to have developed considerable expertise on nuclear power and energy issues.[100]

Health and safety concerns, the 1979 accident at Three Mile Island, and the 1986 Chernobyl disaster played a part in stopping new plant construction in many countries,[91] although the public policy organization, the Brookings Institution states that new nuclear units, at the time of publishing in 2006, had not been built in the U.S. because of soft demand for electricity, and cost overruns on nuclear plants due to regulatory issues and construction delays.[101] By the end of the 1970s it became clear that nuclear power would not grow nearly as dramatically as once believed. Eventually, more than 120 reactor orders in the U.S. were ultimately cancelled[102] and the construction of new reactors ground to a halt. A cover story in the February 11, 1985, issue of Forbes magazine commented on the overall failure of the U.S. nuclear power program, saying it “ranks as the largest managerial disaster in business history”.[103]

Unlike the Three Mile Island accident, the much more serious Chernobyl accident did not increase regulations affecting Western reactors since the Chernobyl reactors were of the problematic RBMK design only used in the Soviet Union, for example lacking "robust" containment buildings.[104] Many of these RBMK reactors are still in use today. However, changes were made in both the reactors themselves (use of a safer enrichment of uranium) and in the control system (prevention of disabling safety systems), amongst other things, to reduce the possibility of a duplicate accident.[105]

An international organization to promote safety awareness and professional development on operators in nuclear facilities was created: WANO; World Association of Nuclear Operators.

Opposition in Ireland and Poland prevented nuclear programs there, while Austria (1978), Sweden (1980) and Italy (1987) (influenced by Chernobyl) voted in referendums to oppose or phase out nuclear power. In July 2009, the Italian Parliament passed a law that cancelled the results of an earlier referendum and allowed the immediate start of the Italian nuclear program.[106] After the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster a one-year moratorium was placed on nuclear power development,[107] followed by a referendum in which over 94% of voters (turnout 57%) rejected plans for new nuclear power.[108]

Nuclear power plant

Just as many conventional thermal power stations generate electricity by harnessing the thermal energy released from burning fossil fuels, nuclear power plants convert the energy released from the nucleus of an atom via nuclear fission that takes place in a nuclear reactor. The heat is removed from the reactor core by a cooling system that uses the heat to generate steam, which drives a steam turbine connected to a generator producing electricity.

Life cycle

A nuclear reactor is only part of the life-cycle for nuclear power. The process starts with mining (see Uranium mining). Uranium mines are underground, open-pit, or in-situ leach mines. In any case, the uranium ore is extracted, usually converted into a stable and compact form such as yellowcake, and then transported to a processing facility. Here, the yellowcake is converted to uranium hexafluoride, which is then enriched using various techniques. At this point, the enriched uranium, containing more than the natural 0.7% U-235, is used to make rods of the proper composition and geometry for the particular reactor that the fuel is destined for. The fuel rods will spend about 3 operational cycles (typically 6 years total now) inside the reactor, generally until about 3% of their uranium has been fissioned, then they will be moved to a spent fuel pool where the short lived isotopes generated by fission can decay away. After about 5 years in a spent fuel pool the spent fuel is radioactively and thermally cool enough to handle, and it can be moved to dry storage casks or reprocessed.

Conventional fuel resources

Uranium is a fairly common element in the Earth's crust. Uranium is approximately as common as tin or germanium in the Earth's crust, and is about 40 times more common than silver.[109] Uranium is a constituent of most rocks, dirt, and of the oceans. The fact that uranium is so spread out is a problem because mining uranium is only economically feasible where there is a large concentration. Still, the world's present measured resources of uranium, economically recoverable at a price of 130 USD/kg, are enough to last for between 70 and 100 years.[110][111][112]

According to the OECD in 2006, there is an expected 85 years worth of uranium in identified resources, when that uranium is used in present reactor technology, with 670 years of economically recoverable uranium in total conventional resources and phosphate ores, while also using present reactor technology, a resource that is recoverable from between 60-100 US$/kg of Uranium.[113] The OECD have noted that:

Even if the nuclear industry expands significantly, sufficient fuel is available for centuries. If advanced breeder reactors could be designed in the future to efficiently utilize recycled or depleted uranium and all actinides, then the resource utilization efficiency would be further improved by an additional factor of eight.

For example, the OECD have determined that with a pure fast reactor fuel cycle with a burn up of, and recycling of, all the Uranium and actinides, actinides which presently make up the most hazardous substances in nuclear waste, there is 160,000 years worth of Uranium in total conventional resources and phosphate ore.[114] According to the OECD's red book in 2011, due to increased exploration, known uranium resources have grown by 12.5% since 2008, with this increase translating into greater than a century of uranium available if the metals usage rate were to continue at the 2011 level.[115][116]

Current light water reactors make relatively inefficient use of nuclear fuel, fissioning only the very rare uranium-235 isotope. Nuclear reprocessing can make this waste reusable, and more efficient reactor designs, such as the currently under construction Generation III reactors achieve a higher efficiency burn up of the available resources, than the current vintage generation II reactors, which make up the vast majority of reactors worldwide.[117]

Breeding

As opposed to current light water reactors which use uranium-235 (0.7% of all natural uranium), fast breeder reactors use uranium-238 (99.3% of all natural uranium). It has been estimated that there is up to five billion years' worth of uranium-238 for use in these power plants.[118]

Breeder technology has been used in several reactors, but the high cost of reprocessing fuel safely, at 2006 technological levels, requires uranium prices of more than 200 USD/kg before becoming justified economically.[119] Breeder reactors are still however being pursued as they have the potential to burn up all of the actinides in the present inventory of nuclear waste while also producing power and creating additional quantities of fuel for more reactors via the breeding process.[120][121] In 2005, there were two breeder reactors producing power: the Phénix in France, which has since powered down in 2009 after 36 years of operation, and the BN-600 reactor, a reactor constructed in 1980 Beloyarsk, Russia which is still operational as of 2013. The electricity output of BN-600 is 600 MW — Russia plans to expand the nation's use of breeder reactors with the BN-800 reactor, was scheduled to become operational in 2014,[122] but due to delays is not scheduled to produce power until 2017.[123] The technical design of a yet larger breeder, the BN-1200 reactor was originally scheduled to be finalized in 2013, with construction slated for 2015 but has also been delayed.[124] Japan's Monju breeder reactor restarted (having been shut down in 1995) in 2010 for 3 months, but shut down again after equipment fell into the reactor during reactor checkups, it is planned to become re-operational in late 2013.[125] Both China and India are building breeder reactors. With the Indian 500 MWe Prototype Fast Breeder Reactor scheduled to become operational in 2014, with plans to build five more by 2020.[126] The China Experimental Fast Reactor began producing power in 2011.[127]

Another alternative to fast breeders is thermal breeder reactors that use uranium-233 bred from thorium as fission fuel in the thorium fuel cycle. Thorium is about 3.5 times more common than uranium in the Earth's crust, and has different geographic characteristics. This would extend the total practical fissionable resource base by 450%.[128] India's three-stage nuclear power programme features the use of a thorium fuel cycle in the third stage, as it has abundant thorium reserves but little uranium.

Solid waste

The most important waste stream from nuclear power plants is spent nuclear fuel. It is primarily composed of unconverted uranium as well as significant quantities of transuranic actinides (plutonium and curium, mostly). In addition, about 3% of it is fission products from nuclear reactions. The actinides (uranium, plutonium, and curium) are responsible for the bulk of the long-term radioactivity, whereas the fission products are responsible for the bulk of the short-term radioactivity.[129]

High-level radioactive waste

High-level radioactive waste management concerns management and disposal of highly radioactive materials created during production of nuclear power. The technical issues in accomplishing this are daunting, due to the extremely long periods radioactive wastes remain deadly to living organisms. Of particular concern are two long-lived fission products, Technetium-99 (half-life 220,000 years) and Iodine-129 (half-life 15.7 million years),[132] which dominate spent nuclear fuel radioactivity after a few thousand years. The most troublesome transuranic elements in spent fuel are Neptunium-237 (half-life two million years) and Plutonium-239 (half-life 24,000 years).[133] Consequently, high-level radioactive waste requires sophisticated treatment and management to successfully isolate it from the biosphere. This usually necessitates treatment, followed by a long-term management strategy involving permanent storage, disposal or transformation of the waste into a non-toxic form.[134]

Governments around the world are considering a range of waste management and disposal options, usually involving deep-geologic placement, although there has been limited progress toward implementing long-term waste management solutions.[135] This is partly because the timeframes in question when dealing with radioactive waste range from 10,000 to millions of years,[136][137] according to studies based on the effect of estimated radiation doses.[138]

Some proposed nuclear reactor designs however such as the American Integral Fast Reactor and the Molten salt reactor can use the nuclear waste from light water reactors as a fuel, transmutating it to isotopes that would be safe after hundreds, instead of tens of thousands of years. This offers a potentially more attractive alternative to deep geological disposal.[139][140][141]

Another possibility is the use of thorium in a reactor especially designed for thorium (rather than mixing in thorium with uranium and plutonium (i.e. in existing reactors). Used thorium fuel remains only a few hundreds of years radioactive, instead of tens of thousands of years.[142]

Since the fraction of a radioisotope's atoms decaying per unit of time is inversely proportional to its half-life, the relative radioactivity of a quantity of buried human radioactive waste would diminish over time compared to natural radioisotopes (such as the decay chains of 120 trillion tons of thorium and 40 trillion tons of uranium which are at relatively trace concentrations of parts per million each over the crust's 3 * 1019 ton mass).[143][144][145] For instance, over a timeframe of thousands of years, after the most active short half-life radioisotopes decayed, burying U.S. nuclear waste would increase the radioactivity in the top 2000 feet of rock and soil in the United States (10 million km2) by ≈ 1 part in 10 million over the cumulative amount of natural radioisotopes in such a volume, although the vicinity of the site would have a far higher concentration of artificial radioisotopes underground than such an average.[146]

Low-level radioactive waste

The nuclear industry also produces a large volume of low-level radioactive waste in the form of contaminated items like clothing, hand tools, water purifier resins, and (upon decommissioning) the materials of which the reactor itself is built. In the US, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission has repeatedly attempted to allow low-level materials to be handled as normal waste: landfilled, recycled into consumer items, etcetera.

Comparing radioactive waste to industrial toxic waste

In countries with nuclear power, radioactive wastes comprise less than 1% of total industrial toxic wastes, much of which remains hazardous for long periods.[117] Overall, nuclear power produces far less waste material by volume than fossil-fuel based power plants.[147] Coal-burning plants are particularly noted for producing large amounts of toxic and mildly radioactive ash due to concentrating naturally occurring metals and mildly radioactive material from the coal.[148] A 2008 report from Oak Ridge National Laboratory concluded that coal power actually results in more radioactivity being released into the environment than nuclear power operation, and that the population effective dose equivalent, or dose to the public from radiation from coal plants is 100 times as much as from the ideal operation of nuclear plants.[149] Indeed, coal ash is much less radioactive than spent nuclear fuel on a weight per weight basis, but coal ash is produced in much higher quantities per unit of energy generated, and this is released directly into the environment as fly ash, whereas nuclear plants use shielding to protect the environment from radioactive materials, for example, in dry cask storage vessels.[150]

Waste disposal

Disposal of nuclear waste is often said to be the Achilles' heel of the industry.[151] Presently, waste is mainly stored at individual reactor sites and there are over 430 locations around the world where radioactive material continues to accumulate. Some experts suggest that centralized underground repositories which are well-managed, guarded, and monitored, would be a vast improvement.[151] There is an "international consensus on the advisability of storing nuclear waste in deep geological repositories",[152] with the lack of movement of nuclear waste in the 2 billion year old natural nuclear fission reactors in Oklo, Gabon being cited as "a source of essential information today."[153][154]

As of 2009 there were no commercial scale purpose built underground repositories in operation.[152][155][156][157] The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in New Mexico has been taking nuclear waste since 1999 from production reactors, but as the name suggests is a research and development facility.

Reprocessing

Reprocessing can potentially recover up to 95% of the remaining uranium and plutonium in spent nuclear fuel, putting it into new mixed oxide fuel. This produces a reduction in long term radioactivity within the remaining waste, since this is largely short-lived fission products, and reduces its volume by over 90%. Reprocessing of civilian fuel from power reactors is currently done in Britain, France and (formerly) Russia, soon will be done in China and perhaps India, and is being done on an expanding scale in Japan. The full potential of reprocessing has not been achieved because it requires breeder reactors, which are not commercially available. France is generally cited as the most successful reprocessor, but it presently only recycles 28% (by mass) of the yearly fuel use, 7% within France and another 21% in Russia.[158]

Reprocessing is not allowed in the U.S.[159] The Obama administration has disallowed reprocessing of nuclear waste, citing nuclear proliferation concerns.[160] In the U.S., spent nuclear fuel is currently all treated as waste.[161]

Depleted uranium

Uranium enrichment produces many tons of depleted uranium (DU) which consists of U-238 with most of the easily fissile U-235 isotope removed. U-238 is a tough metal with several commercial uses—for example, aircraft production, radiation shielding, and armor—as it has a higher density than lead. Depleted uranium is also controversially used in munitions; DU penetrators (bullets or APFSDS tips) "self sharpen", due to uranium's tendency to fracture along shear bands.[162][163]

Economics

Nuclear power plants typically have high capital costs for building the plant, but low fuel costs. Although nuclear power plants can vary their output the electricity is generally less favorably priced when doing so. Nuclear power plants are therefore run as much as possible to keep the cost of the generated electrical energy as low as possible, supplying mostly base-load electricity.

Internationally the price of nuclear plants rose 15% annually in 1970-1990. Total costs rose tenfold. The nuclear plant construction time doubled. According to Al Gore if intended plan does not hold, the delay cost a billion dollars a year.[166] Yet, nuclear power has total costs in 2012 of about $96 per megawatt hour (MWh), most of which involves capital construction costs, compared with solar power at $130 per MWh, and natural gas at the low end at $64 per MWh.[167]

In 2015, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists unveiled the Nuclear Fuel Cycle Cost Calculator, an online tool that estimates the full cost of electricity produced by three configurations of the nuclear fuel cycle. Two years in the making, this interactive calculator is the first generally accessible model to provide a nuanced look at the economic costs of nuclear power; it lets users test how sensitive the price of electricity is to a full range of components—more than 60 parameters that can be adjusted for the three configurations of the nuclear fuel cycle considered by this tool (once-through, limited-recycle, full-recycle). Users can select the fuel cycle they would like to examine, change cost estimates for each component of that cycle, and even choose uncertainty ranges for the cost of particular components. This approach allows users around the world to compare the cost of different nuclear power approaches in a sophisticated way, while taking account of prices relevant to their own countries or regions.

In recent years there has been a slowdown of electricity demand growth and financing has become more difficult, which has an impact on large projects such as nuclear reactors, with very large upfront costs and long project cycles which carry a large variety of risks.[168] In Eastern Europe, a number of long-established projects are struggling to find finance, notably Belene in Bulgaria and the additional reactors at Cernavoda in Romania, and some potential backers have pulled out.[168] Where the electricity market is competitive, cheap natural gas is available, and its future supply relatively secure, this also poses a major problem for nuclear projects[168] and existing plants.[169]

Analysis of the economics of nuclear power must take into account who bears the risks of future uncertainties. To date all operating nuclear power plants were developed by state-owned or regulated utility monopolies[170] where many of the risks associated with construction costs, operating performance, fuel price, accident liability and other factors were borne by consumers rather than suppliers. In addition, because the potential liability from a nuclear accident is so great, the full cost of liability insurance is generally limited/capped by the government, which the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission concluded constituted a significant subsidy.[171] Many countries have now liberalized the electricity market where these risks, and the risk of cheaper competitors emerging before capital costs are recovered, are borne by plant suppliers and operators rather than consumers, which leads to a significantly different evaluation of the economics of new nuclear power plants.[172]

Following the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, costs are expected to increase for currently operating and new nuclear power plants, due to increased requirements for on-site spent fuel management and elevated design basis threats.[173]

The economics of new nuclear power plants is a controversial subject, since there are diverging views on this topic, and multibillion-dollar investments ride on the choice of an energy source. Comparison with other power generation methods is strongly dependent on assumptions about construction timescales and capital financing for nuclear plants as well as the future costs of fossil fuels and renewables as well as for energy storage solutions for intermittent power sources. Cost estimates also need to take into account plant decommissioning and nuclear waste storage costs. On the other hand, measures to mitigate global warming, such as a carbon tax or carbon emissions trading, may favor the economics of nuclear power.

Accidents and safety, the human and financial costs

Some serious nuclear and radiation accidents have occurred. Benjamin K. Sovacool has reported that worldwide there have been 99 accidents at nuclear power plants.[176] Fifty-seven accidents have occurred since the Chernobyl disaster, and 57% (56 out of 99) of all nuclear-related accidents have occurred in the USA.[176][177]

Nuclear power plant accidents include the Chernobyl accident (1986) with approximately 60 deaths so far attributed to the accident and a predicted, eventual total death toll, of from 4000 to 25,000 latent cancers deaths. The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster (2011), has not caused any radiation related deaths, with a predicted, eventual total death toll, of from 0 to 1000, and the Three Mile Island accident (1979), no causal deaths, cancer or otherwise, have been found in follow up studies of this accident.[35] Nuclear-powered submarine mishaps include the K-19 reactor accident (1961),[36] the K-27 reactor accident (1968),[37] and the K-431 reactor accident (1985).[35] International research is continuing into safety improvements such as passively safe plants,[61] and the possible future use of nuclear fusion.

In terms of lives lost per unit of energy generated, nuclear power has caused fewer accidental deaths per unit of energy generated than all other major sources of energy generation. Energy produced by coal, petroleum, natural gas and hydropower has caused more deaths per unit of energy generated, from air pollution and energy accidents. This is found in the following comparisons, when the immediate nuclear related deaths from accidents are compared to the immediate deaths from these other energy sources,[39] when the latent, or predicted, indirect cancer deaths from nuclear energy accidents are compared to the immediate deaths from the above energy sources,[41][42][178] and when the combined immediate and indirect fatalities from nuclear power and all fossil fuels are compared, fatalities resulting from the mining of the necessary natural resources to power generation and to air pollution.[38] With these data, the use of nuclear power has been calculated to have prevented in the region of 1.8 million deaths between 1971 and 2009, by reducing the proportion of energy that would otherwise have been generated by fossil fuels, and is projected to continue to do so.[179][180]

Although according to Benjamin K. Sovacool, fission energy accidents ranked first in terms of their total economic cost, accounting for 41 percent of all property damage attributed to energy accidents.[181] Analysis presented in the international Journal, Human and Ecological Risk Assessment found that coal, oil, Liquid petroleum gas and hydroelectric accidents(primarily due to the Banqiao dam burst) have resulted in greater economic impacts than nuclear power accidents.[42]

Following the 2011 Japanese Fukushima nuclear disaster, authorities shut down the nation's 54 nuclear power plants, but it has been estimated that if Japan had never adopted nuclear power, accidents and pollution from coal or gas plants would have caused more lost years of life.[182] As of 2013, the Fukushima site remains highly radioactive, with some 160,000 evacuees still living in temporary housing, and some land will be unfarmable for centuries. The difficult Fukushima disaster cleanup will take 40 or more years, and cost tens of billions of dollars.[43][44]

Forced evacuation from a nuclear accident may lead to social isolation, anxiety, depression, psychosomatic medical problems, reckless behavior, even suicide. Such was the outcome of the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster in Ukraine. A comprehensive 2005 study concluded that "the mental health impact of Chernobyl is the largest public health problem unleashed by the accident to date".[183] Frank N. von Hippel, a U.S. scientist, commented on the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, saying that "fear of ionizing radiation could have long-term psychological effects on a large portion of the population in the contaminated areas".[184]

Nuclear proliferation

Many technologies and materials associated with the creation of a nuclear power program have a dual-use capability, in that they can be used to make nuclear weapons if a country chooses to do so. When this happens a nuclear power program can become a route leading to a nuclear weapon or a public annex to a "secret" weapons program. The concern over Iran's nuclear activities is a case in point.[185]

A fundamental goal for American and global security is to minimize the nuclear proliferation risks associated with the expansion of nuclear power. If this development is "poorly managed or efforts to contain risks are unsuccessful, the nuclear future will be dangerous".[185] The Global Nuclear Energy Partnership is one such international effort to create a distribution network in which developing countries in need of energy, would receive nuclear fuel at a discounted rate, in exchange for that nation agreeing to forgo their own indigenous develop of a uranium enrichment program. The France-based Eurodif/European Gaseous Diffusion Uranium Enrichment Consortium was/is one such program that successfully implemented this concept, with Spain and other countries without enrichment facilities buying a share of the fuel produced at the French controlled enrichment facility, but without a transfer of technology.[188] Iran was an early participant from 1974, and remains a shareholder of Eurodif via Sofidif.

According to Benjamin K. Sovacool, a "number of high-ranking officials, even within the United Nations, have argued that they can do little to stop states using nuclear reactors to produce nuclear weapons".[189] A 2009 United Nations report said that:

the revival of interest in nuclear power could result in the worldwide dissemination of uranium enrichment and spent fuel reprocessing technologies, which present obvious risks of proliferation as these technologies can produce fissile materials that are directly usable in nuclear weapons.[189]

On the other hand, one factor influencing the support of power reactors is due to the appeal that these reactors have at reducing nuclear weapons arsenals through the Megatons to Megawatts Program, a program which eliminated 425 metric tons of highly enriched uranium(HEU), the equivalent of 17,000 nuclear warheads, by diluting it with natural uranium making it equivalent to low enriched uranium(LEU), and thus suitable as nuclear fuel for commercial fission reactors. This is the single most successful non-proliferation program to date.[186]

The Megatons to Megawatts Program, the brainchild of Thomas Neff of MIT,[190][191] was hailed as a major success by anti-nuclear weapon advocates as it has largely been the driving force behind the sharp reduction in the quantity of nuclear weapons worldwide since the cold war ended.[186] However without an increase in nuclear reactors and greater demand for fissile fuel, the cost of dismantling and down blending has dissuaded Russia from continuing their disarmament.

Currently, according to Harvard professor Matthew Bunn: "The Russians are not remotely interested in extending the program beyond 2013. We've managed to set it up in a way that costs them more and profits them less than them just making new low-enriched uranium for reactors from scratch. But there are other ways to set it up that would be very profitable for them and would also serve some of their strategic interests in boosting their nuclear exports."[192]

Up to 2005, the Megatons to Megawatts Program had processed $8 billion of HEU/weapons grade uranium into LEU/reactor grade uranium, with that corresponding to the elimination of 10,000 nuclear weapons.[193]

For approximately two decades, this material generated nearly 10 percent of all the electricity consumed in the United States (about half of all US nuclear electricity generated) with a total of around 7 trillion kilowatt-hours of electricity produced.[194] Enough energy to energize the entire United States electric grid for about two years.[190] In total it is estimated to have cost $17 billion, a "bargain for US ratepayers", with Russia profiting $12 billion from the deal.[194] Much needed profit for the Russian nuclear oversight industry, which after the collapse of the Soviet economy, had difficulties paying for the maintenance and security of the Russian Federations highly enriched uranium and warheads.[190]

In April 2012 there were thirty one countries that have civil nuclear power plants,[195] of which nine have nuclear weapons, with the vast majority of these nuclear weapons states having first produced weapons, before commercial fission electricity stations. Moreover, the re-purposing of civilian nuclear industries for military purposes would be a breach of the Non-proliferation treaty, of which 190 countries adhere to.

Environmental issues

Life cycle analysis (LCA) of carbon dioxide emissions show nuclear power as comparable to renewable energy sources. Emissions from burning fossil fuels are many times higher.[196][198][199]

According to the United Nations (UNSCEAR), regular nuclear power plant operation including the nuclear fuel cycle causes radioisotope releases into the environment amounting to 0.0002 millisieverts (mSv) per year of public exposure as a global average.[200] (Such is small compared to variation in natural background radiation, which averages 2.4 mSv/a globally but frequently varies between 1 mSv/a and 13 mSv/a depending on a person's location as determined by UNSCEAR).[200] As of a 2008 report, the remaining legacy of the worst nuclear power plant accident (Chernobyl) is 0.002 mSv/a in global average exposure (a figure which was 0.04 mSv per person averaged over the entire populace of the Northern Hemisphere in the year of the accident in 1986, although far higher among the most affected local populations and recovery workers).[200]

Climate change

Climate change causing weather extremes such as heat waves, reduced precipitation levels and droughts can have a significant impact on nuclear energy infrastructure.[201] Seawater is corrosive and so nuclear energy supply is likely to be negatively affected by the fresh water shortage.[201] This generic problem may become increasingly significant over time.[201] This can force nuclear reactors to be shut down, as happened in France during the 2003 and 2006 heat waves. Nuclear power supply was severely diminished by low river flow rates and droughts, which meant rivers had reached the maximum temperatures for cooling reactors.[201] During the heat waves, 17 reactors had to limit output or shut down. 77% of French electricity is produced by nuclear power and in 2009 a similar situation created a 8GW shortage and forced the French government to import electricity.[201] Other cases have been reported from Germany, where extreme temperatures have reduced nuclear power production 9 times due to high temperatures between 1979 and 2007.[201] In particular:

- the Unterweser nuclear power plant reduced output by 90% between June and September 2003[201]

- the Isar nuclear power plant cut production by 60% for 14 days due to excess river temperatures and low stream flow in the river Isar in 2006[201]

Similar events have happened elsewhere in Europe during those same hot summers.[201] If global warming continues, this disruption is likely to increase.

Nuclear decommissioning

The price of energy inputs and the environmental costs of every nuclear power plant continue long after the facility has finished generating its last useful electricity. Once no longer economically viable, nuclear reactors and uranium enrichment facilities are generally decommissioned, returning the facility and its parts to a safe enough level to be entrusted for other uses, such as greenfield status. After a cooling-off period that may last decades, reactor core materials are dismantled and cut into small pieces to be packed in containers for interim storage or transmutation experiments. The process is expensive, time-consuming, dangerous for workers and potentially hazardous to the natural environment as it presents opportunities for human error, accidents or sabotage.[202]

The total energy required for decommissioning can be as much as 50% more than the energy needed for the original construction. In most cases, the decommissioning process costs between US $300 million to US$5.6 billion. Decommissioning at nuclear sites which have experienced a serious accident are the most expensive and time-consuming. In the U.S. in 2011, there are 13 reactors that had permanently shut down and are in some phase of decommissioning.[202] With Yankee Rowe Nuclear Power Station having completed the process in 2007, after ceasing commercial electricity production in 1992. The majority of the 15 years, was used to allow the station to naturally cool-down on its own, which makes the manual disassembly process both safer and cheaper.

Debate on nuclear power

The nuclear power debate concerns the controversy[29][30][96] which has surrounded the deployment and use of nuclear fission reactors to generate electricity from nuclear fuel for civilian purposes. The debate about nuclear power peaked during the 1970s and 1980s, when it "reached an intensity unprecedented in the history of technology controversies", in some countries.[97][203]

Proponents of nuclear energy contend that nuclear power is a sustainable energy source that reduces carbon emissions and increases energy security by decreasing dependence on imported energy sources.[31] Proponents claim that nuclear power produces virtually no conventional air pollution, such as greenhouse gases and smog, in contrast to the chief viable alternative of fossil fuel.[204] Nuclear power can produce base-load power unlike many renewables which are intermittent energy sources lacking large-scale and cheap ways of storing energy.[205] M. King Hubbert saw oil as a resource that would run out, and proposed nuclear energy as a replacement energy source.[206] Proponents claim that the risks of storing waste are small and can be further reduced by using the latest technology in newer reactors, and the operational safety record in the Western world is excellent when compared to the other major kinds of power plants.[207]

Opponents believe that nuclear power poses many threats to people and the environment.[32][33][34] These threats include the problems of processing, transport and storage of radioactive nuclear waste, the risk of nuclear weapons proliferation and terrorism, as well as health risks and environmental damage from uranium mining.[208][209] They also contend that reactors themselves are enormously complex machines where many things can and do go wrong; and there have been serious nuclear accidents.[210][211] Critics do not believe that the risks of using nuclear fission as a power source can be fully offset through the development of new technology. They also argue that when all the energy-intensive stages of the nuclear fuel chain are considered, from uranium mining to nuclear decommissioning, nuclear power is neither a low-carbon nor an economical electricity source.[212][213][214]

Arguments of economics and safety are used by both sides of the debate.

Comparison with renewable energy

As of 2013, the World Nuclear Association has said "There is unprecedented interest in renewable energy, particularly solar and wind energy, which provide electricity without giving rise to any carbon dioxide emission. Harnessing these for electricity depends on the cost and efficiency of the technology, which is constantly improving, thus reducing costs per peak kilowatt".[215]

Renewable electricity production, from sources such as wind power and solar power, is sometimes criticized for being intermittent or variable.[216][217] However, the International Energy Agency concluded that deployment of renewable technologies (RETs), when it increases the diversity of electricity sources, contributes to the flexibility of the system. However, the report also concluded (p. 29): "At high levels of grid penetration by RETs the consequences of unmatched demand and supply can pose challenges for grid management. This characteristic may affect how, and the degree to which, RETs can displace fossil fuels and nuclear capacities in power generation."[218]

Renewable electricity supply in the 20-50+% range has already been implemented in several European systems, albeit in the context of an integrated European grid system.[219] In 2012, the share of electricity generated by renewable sources in Germany was 21.9%, compared to 16.0% for nuclear power after Germany shut down 7-8 of its 18 nuclear reactors in 2011.[220] In the United Kingdom, the amount of energy produced from renewable energy is expected to exceed that from nuclear power by 2018,[221] and Scotland plans to obtain all electricity from renewable energy by 2020.[222] The majority of installed renewable energy across the world is in the form of hydro power.

The IPCC has said that if governments were supportive, and the full complement of renewable energy technologies were deployed, renewable energy supply could account for almost 80% of the world's energy use within forty years.[223] Rajendra Pachauri, chairman of the IPCC, said the necessary investment in renewables would cost only about 1% of global GDP annually. This approach could contain greenhouse gas levels to less than 450 parts per million, the safe level beyond which climate change becomes catastrophic and irreversible.[223]

The cost of nuclear power has followed an increasing trend whereas the cost of electricity is declining for wind power.[224] In about 2011, wind power became as inexpensive as natural gas, and anti-nuclear groups have suggested that in 2010 solar power became cheaper than nuclear power.[225][226] Data from the EIA in 2011 estimated that in 2016, solar will have a levelized cost of electricity almost twice that of nuclear (21¢/kWh for solar, 11.39¢/kWh for nuclear), and wind somewhat less (9.7¢/kWh).[227] However, the US EIA has also cautioned that levelized costs of intermittent sources such as wind and solar are not directly comparable to costs of "dispatchable" sources (those that can be adjusted to meet demand).[228]

From a safety stand point, nuclear power, in terms of lives lost per unit of electricity delivered, is comparable to and in some cases, lower than many renewable energy sources.[38][39][229] There is however no radioactive spent fuel that needs to be stored or reprocessed with conventional renewable energy sources.[230] A nuclear plant needs to be disassembled and removed. Much of the disassembled nuclear plant needs to be stored as low level nuclear waste.[231]

Nuclear renaissance

Since about 2001 the term nuclear renaissance has been used to refer to a possible nuclear power industry revival, driven by rising fossil fuel prices and new concerns about meeting greenhouse gas emission limits.[237] However, the World Nuclear Association has reported that nuclear electricity generation in 2012 was at its lowest level since 1999.[238]

In March 2011 the nuclear emergencies at Japan's Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant and shutdowns at other nuclear facilities raised questions among some commentators over the future of the renaissance.[239][240][241][242][243] Platts has reported that "the crisis at Japan's Fukushima nuclear plants has prompted leading energy-consuming countries to review the safety of their existing reactors and cast doubt on the speed and scale of planned expansions around the world".[244] In 2011 Siemens exited the nuclear power sector following the Fukushima disaster and subsequent changes to German energy policy, and supported the German government's planned energy transition to renewable energy technologies.[245] China, Germany, Switzerland, Israel, Malaysia, Thailand, United Kingdom, Italy[246] and the Philippines have reviewed their nuclear power programs. Indonesia and Vietnam still plan to build nuclear power plants.[247][248][249][250] Countries such as Australia, Austria, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Portugal, Israel, Malaysia, New Zealand, and Norway remain opposed to nuclear power. Following the Fukushima I nuclear accidents, the International Energy Agency halved its estimate of additional nuclear generating capacity built by 2035.[47]

The World Nuclear Association has said that “nuclear power generation suffered its biggest ever one-year fall through 2012 as the bulk of the Japanese fleet remained offline for a full calendar year”. Data from the International Atomic Energy Agency showed that nuclear power plants globally produced 2346 TWh of electricity in 2012 – seven per cent less than in 2011. The figures illustrate the effects of a full year of 48 Japanese power reactors producing no power during the year. The permanent closure of eight reactor units in Germany was also a factor. Problems at Crystal River, Fort Calhoun and the two San Onofre units in the USA meant they produced no power for the full year, while in Belgium Doel 3 and Tihange 2 were out of action for six months. Compared to 2010, the nuclear industry produced 11% less electricity in 2012.[238]

Future of the industry

As already noted, the nuclear power industry in western nations has a history of construction delays, cost overruns, plant cancellations, and nuclear safety issues despite significant government subsidies and support.[103][252][253][254] In December 2013, Forbes magazine reported that, in developed countries, "reactors are not a viable source of new power".[255] Even in developed nations where they make economic sense, they are not feasible because nuclear’s “enormous costs, political and popular opposition, and regulatory uncertainty”.[255] This view echoes the statement of former Exelon CEO John Rowe, who said in 2012 that new nuclear plants “don’t make any sense right now” and won’t be economically viable in the foreseeable future.[255] John Quiggin, economics professor, also says the main problem with the nuclear option is that it is not economically-viable. Quiggin says that we need more efficient energy use and more renewable energy commercialization.[164] Former NRC member Peter Bradford and Professor Ian Lowe have recently made similar statements.[256][257] However, some "nuclear cheerleaders" and lobbyists in the West continue to champion reactors, often with proposed new but largely untested designs, as a source of new power.[255][256][258][259][260][261][262]

Much more new build activity is occurring in developing countries like South Korea, India and China. China has 25 reactors under construction, with plans to build more,[263][264] However, according to a government research unit, China must not build "too many nuclear power reactors too quickly", in order to avoid a shortfall of fuel, equipment and qualified plant workers.[265]

In the US, licenses of almost half its reactors have been extended to 60 years,[266][267] Two new Generation III reactors are under construction at Vogtle, a dual construction project which marks the end of a 34-year period of stagnation in the US construction of civil nuclear power reactors. The station operator licenses of almost half the present 104 power reactors in the US, as of 2008, have been given extensions to 60 years.[266] As of 2012, U.S. nuclear industry officials expect five new reactors to enter service by 2020, all at existing plants.[24] In 2013, four aging, uncompetitive, reactors were permanently closed.[25][26] Relevant state legislatures are trying to close Vermont Yankee and Indian Point Nuclear Power Plant.[26]

The U.S. NRC and the U.S. Department of Energy have initiated research into Light water reactor sustainability which is hoped will lead to allowing extensions of reactor licenses beyond 60 years, provided that safety can be maintained, as the loss in non-CO2-emitting generation capacity by retiring reactors "may serve to challenge U.S. energy security, potentially resulting in increased greenhouse gas emissions, and contributing to an imbalance between electric supply and demand."[268]

There is a possible impediment to production of nuclear power plants as only a few companies worldwide have the capacity to forge single-piece reactor pressure vessels,[269] which are necessary in the most common reactor designs. Utilities across the world are submitting orders years in advance of any actual need for these vessels. Other manufacturers are examining various options, including making the component themselves, or finding ways to make a similar item using alternate methods.[270]

According to the World Nuclear Association, globally during the 1980s one new nuclear reactor started up every 17 days on average, and by the year 2015 this rate could increase to one every 5 days.[271] As of 2007, Watts Bar 1 in Tennessee, which came on-line on February 7, 1996, was the last U.S. commercial nuclear reactor to go on-line. This is often quoted as evidence of a successful worldwide campaign for nuclear power phase-out.[272] Electricity shortages, fossil fuel price increases, global warming, and heavy metal emissions from fossil fuel use, new technology such as passively safe plants, and national energy security may renew the demand for nuclear power plants.

Nuclear phase out

Following the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, the International Energy Agency halved its estimate of additional nuclear generating capacity to be built by 2035.[47][48] Platts has reported that "the crisis at Japan's Fukushima nuclear plants has prompted leading energy-consuming countries to review the safety of their existing reactors and cast doubt on the speed and scale of planned expansions around the world".[244] In 2011, The Economist reported that nuclear power "looks dangerous, unpopular, expensive and risky", and that "it is replaceable with relative ease and could be forgone with no huge structural shifts in the way the world works".[273]

In early April 2011, analysts at Swiss-based investment bank UBS said: "At Fukushima, four reactors have been out of control for weeks, casting doubt on whether even an advanced economy can master nuclear safety . . .. We believe the Fukushima accident was the most serious ever for the credibility of nuclear power".[274]

In 2011, Deutsche Bank analysts concluded that "the global impact of the Fukushima accident is a fundamental shift in public perception with regard to how a nation prioritizes and values its populations health, safety, security, and natural environment when determining its current and future energy pathways". As a consequence, "renewable energy will be a clear long-term winner in most energy systems, a conclusion supported by many voter surveys conducted over the past few weeks. At the same time, we consider natural gas to be, at the very least, an important transition fuel, especially in those regions where it is considered secure".[275]

In September 2011, German engineering giant Siemens announced it will withdraw entirely from the nuclear industry, as a response to the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan, and said that it would no longer build nuclear power plants anywhere in the world. The company’s chairman, Peter Löscher, said that "Siemens was ending plans to cooperate with Rosatom, the Russian state-controlled nuclear power company, in the construction of dozens of nuclear plants throughout Russia over the coming two decades".[276][245] Also in September 2011, IAEA Director General Yukiya Amano said the Japanese nuclear disaster "caused deep public anxiety throughout the world and damaged confidence in nuclear power".[277]

In February 2012, the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission approved the construction of two additional reactors at the Vogtle Electric Generating Plant, the first reactors to be approved in over 30 years since the Three Mile Island accident,[278] but NRC Chairman Gregory Jaczko cast a dissenting vote citing safety concerns stemming from Japan's 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, and saying "I cannot support issuing this license as if Fukushima never happened".[24] One week after Southern received the license to begin major construction on the two new reactors, a dozen environmental and anti-nuclear groups are suing to stop the Plant Vogtle expansion project, saying "public safety and environmental problems since Japan's Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor accident have not been taken into account".[279]

Countries such as Australia, Austria, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Israel, Malaysia, New Zealand, and Norway have no nuclear power reactors and remain opposed to nuclear power.[273][280] However, by contrast, some countries remain in favor, and financially support nuclear fusion research, including EU wide funding of the ITER project.[281][282]

Worldwide wind power has been increasing at 26%/year, and solar power at 58%/year, from 2006 to 2011, as a replacement for thermal generation of electricity.[283]

Advanced concepts

Current fission reactors in operation around the world are second or third generation systems, with most of the first-generation systems having been retired some time ago. Research into advanced generation IV reactor types was officially started by the Generation IV International Forum (GIF) based on eight technology goals, including to improve nuclear safety, improve proliferation resistance, minimize waste, improve natural resource utilization, the ability to consume existing nuclear waste in the production of electricity, and decrease the cost to build and run such plants. Most of these reactors differ significantly from current operating light water reactors, and are generally not expected to be available for commercial construction before 2030.[284]

The nuclear reactors to be built at Vogtle are new AP1000 third generation reactors, which are said to have safety improvements over older power reactors.[278] However, John Ma, a senior structural engineer at the NRC, is concerned that some parts of the AP1000 steel skin are so brittle that the "impact energy" from a plane strike or storm driven projectile could shatter the wall.[285] Edwin Lyman, a senior staff scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, is concerned about the strength of the steel containment vessel and the concrete shield building around the AP1000.[285][286]

The Union of Concerned Scientists has referred to the EPR (nuclear reactor), currently under construction in China, Finland and France, as the only new reactor design under consideration in the United States that "...appears to have the potential to be significantly safer and more secure against attack than today's reactors."[287]

One disadvantage of any new reactor technology is that safety risks may be greater initially as reactor operators have little experience with the new design. Nuclear engineer David Lochbaum has explained that almost all serious nuclear accidents have occurred with what was at the time the most recent technology. He argues that "the problem with new reactors and accidents is twofold: scenarios arise that are impossible to plan for in simulations; and humans make mistakes".[288] As one director of a U.S. research laboratory put it, "fabrication, construction, operation, and maintenance of new reactors will face a steep learning curve: advanced technologies will have a heightened risk of accidents and mistakes. The technology may be proven, but people are not".[288]

Hybrid nuclear fusion-fission

Hybrid nuclear power is a proposed means of generating power by use of a combination of nuclear fusion and fission processes. The concept dates to the 1950s, and was briefly advocated by Hans Bethe during the 1970s, but largely remained unexplored until a revival of interest in 2009, due to delays in the realization of pure fusion. When a sustained nuclear fusion power plant is built, it has the potential to be capable of extracting all the fission energy that remains in spent fission fuel, reducing the volume of nuclear waste by orders of magnitude, and more importantly, eliminating all actinides present in the spent fuel, substances which cause security concerns.[289]

Nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion reactions have the potential to be safer and generate less radioactive waste than fission.[290][291] These reactions appear potentially viable, though technically quite difficult and have yet to be created on a scale that could be used in a functional power plant. Fusion power has been under theoretical and experimental investigation since the 1950s.

Construction of the ITER facility began in 2007, but the project has run into many delays and budget overruns. The facility is now not expected to begin operations until the year 2027 – 11 years after initially anticipated.[292] A follow on commercial nuclear fusion power station, DEMO, has been proposed.[21][293] There is also suggestions for a power plant based upon a different fusion approach, that of a Inertial fusion power plant.

Fusion powered electricity generation was initially believed to be readily achievable, as fission-electric power had been. However, the extreme requirements for continuous reactions and plasma containment led to projections being extended by several decades. In 2010, more than 60 years after the first attempts, commercial power production was still believed to be unlikely before 2050.[21]

Nuclear power organizations

There are multiple organizations which have taken a position on nuclear power – some are proponents, and some are opponents.

Proponents

- Environmentalists for Nuclear Energy (International)

- Nuclear Industry Association (United Kingdom)

- World Nuclear Association, a confederation of companies connected with nuclear power production. (International)

- International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)

- Nuclear Energy Institute (United States)

- American Nuclear Society (United States)

- United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (United Kingdom)

- EURATOM (Europe)

- European Nuclear Education Network (Europe)

- Atomic Energy of Canada Limited (Canada)

Opponents

- Friends of the Earth International, a network of environmental organizations.[294]

- Greenpeace International, a non-governmental organization[295]

- Nuclear Information and Resource Service (International)

- World Information Service on Energy (International)

- Sortir du nucléaire (France)

- Pembina Institute (Canada)

- Institute for Energy and Environmental Research (United States)

- Sayonara Nuclear Power Plants (Japan)

See also

- Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- German nuclear energy project

- Linear no-threshold model

- Nuclear power in France

- Nuclear weapons debate

- Harry Shearer's Le Show— a weekly radio show and podcast featuring "Clean, Safe, Too Cheap to Meter", a series of regular updates on nuclear power

- Uranium mining debate

- World energy consumption

References

- ↑ Nuclear Energy: Statistics, Dr. Elizabeth Ervin

- ↑ "An oasis filled with grey water". NEI Magazine. 2013-06-25.

- ↑ Topical issues of infrastructure development IAEA 2012

- ↑ "2014 Key World Energy Statistics" (PDF). http://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/. IEA. 2014. p. 24. Archived from the original on 2014-05-05. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Nuclear Energy". Energy Education is an interactive curriculum supplement for secondary-school science students, funded by the U. S. Department of Energy and the Texas State Energy Conservation Office (SECO). U. S. Department of Energy and the Texas State Energy Conservation Office (SECO). July 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- 1 2 "Key World Energy Statistics 2012" (PDF). International Energy Agency. 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-16.