Kingdom of Nri

| Kingdom of Nri | |||||

| Ọ̀ràézè Ǹrì | |||||

| |||||

Nri's area of influence (green) with West Africa's modern borders | |||||

| Capital | Igbo-Ukwu[1] | ||||

| Languages | Igbo | ||||

| Religion | Odinani | ||||

| Government | Elective monarchy | ||||

| Sacred king | |||||

| • | 948 | Eri | |||

| Ézè | |||||

| • | 1043—1089 | Eze Nri Ìfikuánim | |||

| • | 1988—present | Eze Nri Ènweleána II Obidiegwu Onyeso | |||

| History | |||||

| • | Established | 948 | |||

| • | Surrender to Britain | 1911 | |||

| • | Socio-political revival | 1974 | |||

| Currency | Okpogho | ||||

The Kingdom of Nri (Igbo: 'Ọ̀ràézè Ǹrì') (948–1911) was the West African medieval region in southeastern Nigeria, a subgroup of the Igbo speaking people. The Kingdom of Nri was unusual in the history of world government in that its leader exercised no military power over his subjects. The kingdom existed as a sphere of religious and political influence over a third of Igboland, and was administered by a priest-king called as an Eze Nri. The Eze Nri managed trade and diplomacy on behalf of the Igbo people, and possessed divine authority in religious matters.

The kingdom was a safe haven for all those who had been rejected in their communities and also a place where slaves were set free from their bondage. Nri expanded through converts gaining neighboring communities' allegiance, not by force. Nri's royal founder, Eri, is said to be a 'sky being' that came down to earth and then established civilization. One of the better-known remnants of the Nri civilization is its art, as manifested in the Igbo Ukwu bronze items.

Nri's culture had permanently influenced the Northern and Western Igbo, especially through religion and taboos. British colonialism, the Atlantic slave trade and the rise of Bini and Igala kingdoms, contributed to the decline of the Nri Kingdom. The Nri Kingdom is going through a cultural revival.

History

The Nri kingdom is considered to be a center of Igbo culture.[2] Nri and Aguleri, where the Umueri-Igbo creation myth originates, are in the territory of the Umu-Eri clan, who trace their lineages back to the patriarchal king-figure, Eri.[3] Eri's origins are unclear, though he has been described as a "sky being"[3] sent by Chukwu (God).[4] He is credited with first giving societal order to the people of Anambra.[4] Nri history may be divided into six main periods: the pre-Eri period (before 948 CE), the Eri period (948—1041 CE), migration and unification (1042—1252 CE), the heyday of Nri hegemony (1253—1679 CE), hegemony decline and collapse (1677—1936 CE) and the Socio-culture Revival (1974—Present).[5]

Foundation

Archaeological evidence suggests that Nri hegemony in Igboland may go back as far as the 9th century,[6] and royal burials have been unearthed dating to at least the 10th century. Eri, the god-like founder of Nri, is believed to have settled the region around 948, with other related Igbo cultures following after in the 13th century.[7][8] The first eze Nri (King of Nri), Ìfikuánim, follows directly after him. According to Igbo oral tradition, his reign started in 1043.[8] At least one historian puts Ìfikuánim's reign much later, around 1225 CE.[9]

In 1911, the names of 19 eze Nri were recorded, but the list is not easily converted into chronological terms because of long interregnums between installations.[3] Tradition held that at least seven years would pass upon the death of the eze Nri before a successor could be determined; the interregnum served as a period of divination of signs from the deceased eze Nri, who would communicate his choice of successor from beyond the grave in the seven or more years ensuing upon his death. Regardless of the actual date, this period marks the beginning of Nri kingship as a centralized institution.

Zenith and fall

Colonization and expansion of the kingdom of Nri was achieved by sending mbùríchi, or converts, to other settlements. Allegiance to the eze Nri was obtained not by military force but through ritual oath. Religious authority was vested in the local king, and ties were maintained by traveling mbùríchi. By the 14th century, Nri influence extended well beyond the nuclear northern Igbo region to Igbo settlements on the west bank of the Niger and communities affected by the Benin Empire.[6] There is strong evidence to indicate Nri influence well beyond the Igbo region to Benin and Southern Igala areas like Idah. At its height, the kingdom of Nri had influence over roughly a third of Igboland and beyond. It reached its furthest extent between 1100 and 1400.[3]

Nri's hegemony over much of Igboland lasted from the reigns of the fourth eze Nri to that of the ninth. After that, patterns of conflict emerged that existed from the tenth to the fourteenth reigns, which probably reflected the monetary importance of the slave trade.[7] Outside-world influence was not going to be halted by native religious doctrine in the face of the slave trade's economic opportunities. Nri hegemony declined after the start of the 18th century.[10] Still, it survived in a much-reduced, and weakened form until 1911. In 1911, British troops forced the reigning eze Nri to renounce the ritual power of the religion known as the ìkénga, ending the kingdom of Nri as a political power.[10]

Government

Nearly all communities in Igboland were organized according to a title system. Igbo west of the Niger River and on its east bank developed kingship, governing states such as Aboh, Onitsha and Oguta, their title Obi.[11][N 1] The Igbo of Nri, on the other hand, developed a state system sustained by ritual power.[6]

The Kingdom of Nri was a religio-polity, a sort of theocratic state, that developed in the central heartland of the Igbo region.[7] The Nri had a taboo symbolic code with six types. These included human (such as twins), animal, object, temporal, behavioral, speech and place taboos. The rules regarding these taboos were used to educate and govern Nri's subjects. This meant that, while certain Igbo may have lived under different formal administration, all followers of the Igbo religion had to abide by the rules of the faith and obey its representative on earth, the eze Nri.[12]

An important symbol among the Nri religion was the omu, a tender palm frond, used to sacralize and restrain. It was used as protection for traveling delegations or safeguarding certain objects; a person or object carrying an omu twig was considered protected.[12] The influence of these symbols and institutions extended well beyond Nri, and this unique Igbo socio-political system proved capable of controlling areas wider than villages or towns.[11]

For many centuries, the people within the Nri hegemony were committed to peace. This religious pacifism was rooted in a belief that violence was an abomination which polluted the earth.[3] Instead, the eze Nri could declare a form of excommunication from the odinani Nri against those who violated specific taboos. Members of the Ikénga could isolate entire communities via this form of ritual siege.[10]

Eze Nri

The eze Nri was the title of the ruler of Nri with ritual and mystic (but not military) power.[11] He was a ritual figure rather than a king in the traditional sense. The eze Nri was chosen after an interregnum period while the electors waited for supernatural powers to manifest in the new eze Nri. He was installed after a symbolic journey to Aguleri on the Anambra River.[3]The authorities must be notified prior to commencement of this journey to obtain the Ududu-eze,the royal scepter. There, the process of paying of homage to all the necessary shrines/deities in Aguleri by the new Eze Nri, visitation to Menri`s tomb at Ama-Okpu, collection of Ofo, purification of the virgin boy to receive the clay from the chosen diver from Umuezeora in Aguleri, sitting on the throne of Eri at Obu-Gad in Aguleri by the new Eze-Nri before going back to Nri on the seventh day to undergo a symbolic burial and exhumation, then finally be anointed with white clay, a symbol of purity. Upon his death, he was buried seated in a wood-lined chamber.[3] The eze Nri was in all aspects a divine ruler.

Ìkénga

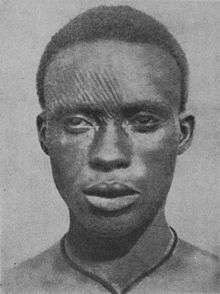

While the eze Nri lived relatively secluded from his followers, he employed a group of Jesuit-like officials called ndi Nri.[13] These were ritual specialists, easily identifiable by facial scarifications or ichi,[13] who traveled with ritual staffs of peace in order to purify the earth from human crimes.[3] The ndi Nri exercised authority over wide areas of Igboland and had the power to install the next eze Nri.[11]

Areas under Nri influence, called Odinani Nri, were open to Ndi Nri traveling within them to perform rituals and ensure bountiful harvest or restore harmony in local affairs.[7] Local men within the odinani Nri could represent the eze Nri and share his moral authority by purchasing a series of ranked titles called Ozo and Nze. Men with these titles were known as mbùríchi and became an extension of the Nri's religio-political system. They controlled the means for agriculture and determined guilt or innocence in disputes.[10]

Both the Ndi Nri priests and mbùríchi nobility belonged to the Ikénga, the right hand. The Ìkénga god was one dedicated to achievement and power, both of which were associated with the right hand.[3]

Economy

Nri maintained its vast authority well into the 16th century.[2] The peace mandated by the Nri religion and enforced by the presence of the mbùríchi allowed trade to flourish. Items such as horses, which did not survive in tsetse fly-infested Nri, and seashells, which would have to be transported a long ways due to Nri's distance from the coast, have been found depicted in Nri's bronze. A Nri dignitary was unearthed with ivory, also indicating a wealth in trade existed among the Nri.[3] Another source of income would have been the income brought back by traveling mbùríchi.[11]

Unlike in many African economies of the period, Nri did not practice slave ownership or trade. Certain parts of the Nri domain, did not recognize slavery and served as a sanctuary. After the selection of the tenth eze Nri, any slave who stepped foot on Nri soil was considered free.[10]

Nri had a network of internal and external trade, which its economy was partly based on. Other aspects of Nri's economy were hunting and agriculture.[14] Eri, the sky being, was the first to 'count' the days by their names, eke, oye, afor and nkwo, which were the names of their four governing spirits. Eri revealed the opportunity of time to the Igbo, who would use the days for exchanging goods and knowledge.[15]

Culture

Art

Igbo-Ukwu, a part of the kingdom about nine miles from Nri itself, practiced bronze casting techniques using elephant-head motifs.[3][6] The bronzes of Igbo-Ukwu are often compared to those of Ife and Benin, but they come from a different tradition and are associated with the eze Nri.[11] In fact, the earliest body of Nigerian bronzes has been unearthed in Igbo territory to the east of the Niger River at a site dated to the 9th century, making it (and, by extension, Nri) older than Ife.[16]

It appears that Nri had an artistic as well as religious influence on the lower Niger. Sculptures found there are bronze like those at Igbo-Ukwu. The great sculptures of the Benin Empire, by contrast, were almost always brass with, over time, increasingly greater percentages of zinc added.[6]

The bronzes of Igbo-Ukwu pay special attention to detail depicting birds, snails, chameleons, and other natural aspects of the world such as a hatching bird. Other pieces include gourds and vessels which were often given handles. The pieces are so fine that small insects were included on the surfaces of some while others have what looks like bronze wires decorated around them. None of these extra details were made separately; the bronzes were all one piece. Igbo-Ukwu gave the evidence of an early bronze casting tradition in Nri.[17]

Religion

Religious beliefs were central to the Kingdom of Nri.[18] Nri oral tradition states that a bounty of yams and cocoyams could be given to the eze Nri, while blessings were given in return.[3] It was believed that Nri's influence and bountiful amount of food was a reward for the ruler's blessings.[3] Above all, Nri was a holy land for those Igbo who followed its edicts. It served as a place where sins and taboos could be absolved just by entering it. Even Igbo living far from the center of power would send abnormal children to Nri for ritual cleansing rather than having them killed, as was sometimes the case for dwarfs or children who cut their top teeth before their lower teeth.[19]

Nri people believed that the sun was the dwelling place of Anyanwu (Light) and Agbala (Fertility). Agbala was the collective spirit of all holy beings (human and nonhuman). Agbala was the perfect agent of Chukwu or Chineke (the Creator God) and chose its human and nonhuman agents only by their merit; it knew no politics. It transcended religion, culture and gender, and worked with the humble and the truthful. They believed Anyanwu, The Light, to be the symbol of human perfection that all must seek and Agbala was entrusted to lead man there.[20]

Tradition

Nri tradition was based on the concept of peace, truth and harmony.[21] It spread this ideology through the ritualistic Ozo traders who maintained Nri influence by traveling and spreading Nri practices such as the "Ikenga" to other communities. These men were identified through the ritual facial scarifications they had undergone. Nri believed in cleansing and purifying the earth (a supernatural force to Nri called Ana and Ajana)[21] of human abominations and crimes.[3]

Year counting ceremony

The Igu Aro festival (counting of the year)[22] was a royal festival the eze Nri used to maintain his influence over the communities under his authority. Each of these communities sent representatives to pay tribute during the ceremony to show their loyalty. At the end the Eze Nri would give the representatives a yam medicine and a blessing of fertility for their communities.[23] The festival was seen as a day of peace and certain activities were prohibited such as the planting of crops before the day of the ceremony, the splitting of wood and unnecessary noise.[22] Igu Aro was a regular event that gave an opportunity for the eze to speak directly to all the communities under him.

Nri scarification

Ritual scarification in Nri was known as Ichi of which there are two styles; the Nri style, and the Agbaja style. In the Nri style, the carved line ran from the center of the forehead down to the chin. A second line ran across the face, from the right cheek to the left. This was repeated to obtain a pattern meant to imitate the rays of the sun. In the Agbaja style, circles and semicircular patterns are added to the initial incisions to represent the moon. These scarifications were given to the representatives of the eze Nri; the mbùríchi.[13] The scarification's were Nri's way of honoring the sun that they worshiped and was a form of ritual purification.[25]

Scarification had its origins in Nri mythology. Nri, the son of Eri who established the town of Nri, was said to have pleaded to Chukwu (the Great God) because of hunger. Chukwu then ordered him to cut off his first son's and daughter's heads and plant them, creating a 'blood bond' between the Igbo and the earth deity, Ana. Before doing so, Nri was ordered to mark ichi onto their two foreheads. Coco yam, a crop managed by females, sprang from his daughter's head, and yam, the Igbo peoples' staple crop, sprung from his son's head; Chukwu had taught Nri plant domestication. From this, the eze Nri's first son and daughter were required to undergo scarification's seven days after birth, with the eze Nri's daughter being the only female to receive ichi.[26] Nri, the son of Eri, also gained knowledge of the yam medicine (ogwu ji). People from other Igbo communities made pilgrimages to Nri in order to receive this knowledge received in exchange for annual tributes.[27][28]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Ehret, page 315.

- 1 2 Griswold, page XV

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Isichei, page 246—247

- 1 2 Uzukwu, page 93

- ↑ Onwuejeogwu (1981), page 22

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hrbek, page 254

- 1 2 3 4 Lovejoy, page 62

- 1 2 Onwuejeogwu, M. Angulu (1981). Igbo Civilization: Nri Kingdom & Hegemony. Ethnographica. pp. 22–25. ISBN 0-905788-08-7.

- ↑ Chambers, page 33

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lovejoy, page 63

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ogot, page 229

- 1 2 Nyang, page 130

- 1 2 3 Chambers, page 31

- ↑ Nwachuku, page 5

- ↑ Uzukwu, 107

- ↑ Hrbek, page 252

- ↑ Garlake, page 119—120

- ↑ Isichei, page 85

- ↑ Lovejoy, page 70

- ↑ Uzukwu, page 31

- 1 2 Onwuejeogwu (1981), page 11

- 1 2 Basden (1912), page 71

- ↑ Onwuejeogwu (1975), page 44

- ↑ Basden (1921), page 184

- ↑ Thomas, page 413—414.

- ↑ Isichei, page 247

- ↑ Amadiume, page 28

- ↑ Uzukwu, page 104

References

- ↑ Apparently from the Benin Empire's Oba, this is debatable however, because the word "obi" in most Igbo dialects literally means "heart" and may be a metaphorical reference to kingship, rather than a loanword from Yoruba or Edo)

Sources

- Juang, Richard M. (2008). Africa and the Americas: culture, politics, and history : a multidisciplinary encyclopedia, Volume 2. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-441-5.

- Anunobi, Chikodi (2006). Nri Warriors of Peace. Zenith Publisher's Trade Paperback original. ISBN 0-9767303-0-8.

- Chambers, Douglas (2005). Murder At Montpelier: Igbo Africans In Virginia. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1-57806-706-5.

- Thomas, Julian (2000). Interpretive archaeology: a reader. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-7185-0192-6.

- Onwuejeogwu, M. Angulu (1981). An Igbo civilization: Nri kingdom & hegemony. Ethnographica. ISBN 978-123-105-X.

- Onwuejeogwu, M. Angulu (1975). The social anthropology of Africa: an introduction. Heinemann. ISBN 0-435-89701-2.

- Griswold, Wendy (2000). Bearing Witness: Readers, Writers, and the Novel in Nigeria. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05829-6.

- Basden, George Thomas (1966). Among the Ibos of Nigeria 1912. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-1633-8.

- Basden, George Thomas (1921). Among the Ibos of Nigeria: An Account of the Curious & Interesting Habits, Customs & Beliefs of a Little Known African People, by One who Has for Many Years Lived Amongst Them on Close & Intimate Terms. Seeley, Service. p. 184.

- Uzukwu, E. Elochukwu (1997). Worship as body language: introduction to Christian worship : an African orientation. Liturgical Press. ISBN 0-8146-6151-3.

- Nwachuku, Levi Akalazu; Uzoigwe, G. N. (2004). Troubled journey: Nigeria since the civil war. University Press of America. ISBN 0-7618-2712-9.

- Garlake, Peter S. (2002). Early art and architecture of Africa. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-284261-7.

- Thomas, Julian (2000). Interpretive archaeology: a reader. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-7185-0192-6.

- Fasi, Muhammad; Hrbek, Ivan (1988). Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century. London: Heinemann. ISBN 0-435-94809-1.

- Ehret, Christopher (2002). The civilizations of Africa: a history to 1800. James Currey Publishers. ISBN 0-85255-475-3.

- Isichei, Elizabeth Allo (1997). A History of African Societies to 1870. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45599-5.

- Lovejoy, Paul (2000). Identity in the Shadow of Slavery. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8264-4725-2.

- Nyang, Sulayman; Olupona, Jacob K. (1995). Religious Plurality in Africa: Essays in Honour of John S. Mbiti. Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-014789-6.

- Amadiume, Ifi (1992). Male daughters, female husbands: gender and sex in an African society (3 ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-86232-595-1.

- Ogot, Bethwell A. (1992). Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. University of California Press. ISBN 0-435-94811-3.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||