North End, Halifax

| North End | |

|---|---|

| Neighbourhood | |

|

Agricola Street | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Nova Scotia |

| Municipality | Halifax Regional Municipality |

| Community council | Peninsula Council |

| Planning Area | Halifax Peninsula |

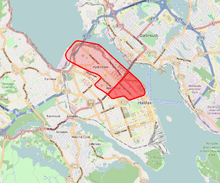

The North End of Halifax is a neighbourhood in Halifax, Nova Scotia occupying the northern part of Halifax Peninsula immediately north of Downtown Halifax.

Geography

The northern part of the Halifax Peninsula comprises thin soil resulting from glacial deposits, as well as outcroppings of a dark sedimentary shale known as "ironstone". The entire peninsula has no significant surface water, unlike the areas northeast and southwest of Halifax Harbour (the Eastern Shore and South Shore respectively).

At 60 m in elevation, Citadel Hill is the highest point on the peninsula and when combined with the expansive undeveloped parkland of the North Common, creates a physical boundary that separates the various neighbourhoods. Fort Needham is another glacial drumlin located in the heart of the North End.

Boundaries

The neighbourhood referred to as the "North End" by Halifax residents was bounded on the east by "The Narrows" of Halifax Harbour and on the north by Bedford Basin. Its other boundaries as not as sharply defined, but the western limit of the neighbourhood is generally agreed to be Windsor street. The southern boundary was, traditionally, the northern limit of General Cornwallis's original Halifax settlement along the slope of Citadel Hill (now Cogswell Street), and continuing along the northern edge of the North Common to Quinpool Road.

The northern boundary has steadily migrated toward the Bedford Basin since Halifax's founding. The boundary originally ended at North Street, just as the South End ended at South Street. Another community further to the north was Richmond, and was located on the eastern slope of Fort Needham. Further north of Richmond, at the end of the Campbell Road, was the black community of Africville.

By the end of the 19th century, the perception of the North End had come to generally include Richmond as well. Following its total destruction in the Halifax Explosion (December 1917), Richmond never again regained its individual identity. The area underwent significant redevelopment during the inter-war period and gradually became an extension of the original North End.

Africville held out as a separate community until the 1960s when it was demolished by city authorities and its residents were relocated, many to public housing projects such as Uniacke Square. With the removal of Africville, public perception of the northern boundary then extended to the shores of the Bedford Basin.

During the same time period, the perception of the southern boundary became less clear, with some contending the North End starts at North Street, and that the original north suburb is in fact a part of central Halifax.

History

The North End of Halifax began as an agricultural expansion north from central Halifax as German Foreign Protestant settlers arrived. It became the focus of industry in Halifax with the construction of the Nova Scotia Railway in the 1850s which located its terminal in the north end. Factories such as the Acadia Sugar Refinery, Hillis & Sons Foundry, and the Nova Scotia Cotton Manufacturing Company followed making the North End the focus of manufacturing in Halifax. Wharves warehouses lined the waterfront, along with the city's prison at Rockhead and major defence installations such as HMC Dockyard and Stadacona (formerly HMCS Stadacona and Wellington Barracks, now part of CFB Halifax). The North End is best known for the disaster of 6 December 1917, commonly referred to as the Halifax Explosion.

The explosion's aftermath saw the area north of North Street razed and a new street grid was superimposed o the old street patterns. New residential construction saw the creation of the historic Hydrostone neighbourhood, built during the relief construction following the disaster. Today the memorial bells at Fort Needham, which were recovered from a church that didn't survive the event, may be heard in the carillon and monument to the disaster. The Memorial was designed by Nova Scotia architect Keith L. Graham. The Halifax Shipyard was built in 1918 beside the Naval Dockyard, further entrenching the industrial character of the North End.

The Halifax North Memorial Public Library, also designed by Keith L. Graham, was opened in 1966 in memory of the victims of the explosion. Located on Göttingen Street, south of North Street, the library offers a welcoming environment as well as programs that strongly reflect the diverse make-up of the community.

Seaview Park on the Bedford Basin is the site of Africville, the former African-Canadian community that was a safe haven for African slaves coming to Canada. The community was torn down in the 1960s preceding a proposed urban redevelopment of the region which would see new highways and the construction of the A. Murray MacKay Bridge, although the lands of the community were never used in a proposed port expansion. In the ensuing controversy it was designated as parkland.

The Africville expropriation is often characterized as an example of institutional racism in Halifax. The municipal government justified the destruction of Africville by citing the poor living conditions of the community, despite having historically refused to extend those services to the community. The razing of Africville allowed for industrial development in the area and for the progress of the city's traffic grid, with the construction of the 'new' bridge. The Africville residents and descendants were dispersed among some of the North End's public housing projects, as well as into other parts of Halifax and Dartmouth.

Features

Commercial centres

Gottingen Street is the commercial and entertainment heart of the North End. It is home to numerous shops, bars, clubs, and performance venues. In the early to mid-20th century, the street was the beating heart of the North End. In 1950, the four blocks of Gottingen closest to downtown boasted more than 130 enterprises, including two cinemas.[1] The street declined in stature as the peninsula lost population during the latter half of the 20th century, and as a result of car-oriented urban renewal schemes. Many nearby residences were demolished when the northern part of Barrington Street was transformed into a highway to serve the Macdonald Bridge, and when the Cogswell Interchange was built. Additionally, several blocks of houses and apartment buildings were demolished in 1958 in an attempt to boost patronage on Gottingen by providing additional car parking. Seven new parking lots were built, displacing local residents to other areas, but this had "no positive impact on the vitality of the Gottingen Street commercial district".[2]

The Gottingen Street area population declined from high of 11,939 (1951) to a low of 4,494 (1996).[1] However, in recent years the trend has reversed as more housing is built in the area and as vacant lots have been developed. The population has risen substantially since the 1990s, resulting in a mix of new businesses opening up.

A few blocks away Agricola Street, which runs parallel to Gottingen Street, is another commercial district home to many local shops, restaurants, and galleries. It has also benefited from new residential developments that have increased the local population.

The shops of The Hydrostone serve as the commercial centre of the northern half of the North End.

Historic buildings

The North End is home to several historic churches. The Little Dutch Church, adapted as a church in 1756, is the second-oldest building in the city. St. George's Church is a unique round church at the corner of Brunswick and Cornwallis Streets completed in 1801. It was badly burned in an accidental 1994 fire. Prince Charles, who had visited the church in 1983 with Princess Diana, was among those who donated toward its reconstruction. The restoration was completed in 2000. The St. Patrick's Church, also on Brunswick Street, was founded in 1843 and rebuilt in its present form in 1885.[3] The Africville Church, established in 1849 and razed under cover of darkness in 1969, was reconstructed in 2011 as part of the Africville Apology.

The Halifax Armoury, on North Park Street, is a National Historic Site. The massive Romanesque Revival building resembles a old castle, but it boasted numerous technological innovations when it opened in 1899, including the adoption of electricity and the truss structure that permitted a large interior space with no columns or walls.[4] HMCS Stadacona is home to numerous other historic military buildings.

Military installations

The North End is home to several of military installations within CFB Halifax, the country's largest military base. Her Majesty's Canadian Dockyard (HMC Dockyard Halifax) is a sprawling complex that occupies the harbourfront area next to the traditional North End. Stadacona, on the opposite side of Barrington Street, is host to barracks and a host of supporting facilities housed in both historic and modern structures. In the centre of the peninsula, away from the shoreline, Windsor Park and Willow Park are home to base transport and supply, housing, the Canadian Forces Exchange System, the curling club, the Military Police, and the Military Family Resource Centre.

The North End is also home to the Halifax Shipyard, sited just to the north of HMC Dockyard. Founded in 1889, the shipyard has built many vessels for the Royal Canadian Navy and is the largest full-service shipyard on the east coast. In 2011 the shipyard was selected to build the navy's new combat fleet, comprising 21 vessels costing $25 billion over a period of 30 years.[5] Irving Shipbuilding, owner of the shipyard, has undertaken a $300 million upgrade of the facility, boasting that Halifax will have "the most modern shipyard in North America".[6] The shipbuilding contract is expected to employ between 2,000 and 2,500 people at the height of construction in 2021.[6]

Reputation

In recent years, the North End has become a popular destination for Halifax's growing university population. As the prices of apartments closer to Dalhousie University and Saint Mary's University continue to rise, and as the cost of transportation has fallen due to the introduction of the U-pass, students are finding cheaper accommodations in the North End. This has spawned a thriving artistic community, with many painters, musicians and writers being lured to this colourful section of the city.

However, the North End is often linked to issues of crime and poverty. Its historic reputation as a largely blue collar, African Canadian, working class area[7] remains in the minds of much of the local population, especially the older citizens. Hugh MacLennan, in his 1941 novel of the Halifax Explosion, Barometer Rising described the North End as having always been "Catholic and poor". Land use has been defined by the proximity of the CFB Halifax naval base and various adjunct facilities, as well as the Halifax Shipyard, the devastation of the 1917 explosion, all of which contributed to a now-aging stock of residential and commercial buildings that are typically smaller and of lower assessed value than other areas in the metropolitan region. Socio-economically, the devastation of the explosion and the military and industrial concentration in the neighbourhood saw a flight of the middle class to other exclusively residential undevastated neighbourhoods during the early 20th century, leading to a decline in the reputation of the North End.

A perceived media bias against the North End, and media confusion over boundaries, continues to generate controversy among residents, who believe they are targeted for racial and/or socio-economic reasons. Low rent in the smaller residential and commercial properties had contributed to a trend toward gentrification in recent decades, often spearheaded by artistic, cultural and activist organizations. The recent housing boom of the early 21st century has again re-valued property on the Halifax peninsula.

The area has become home to organizations such as Bloomfield Centre,[8] North By North End,[9] Grainery Food Co-Op,[10] the Anchor Archive Zine Library,[11] Turnstile Pottery Cooperative, Nova Scotia Youth Project, and the North End Community Gardening Association.[12] Plans are now under way for the redevelopment of Bloomfield Centre.[13]

Education

- Citadel High School

- Ecole Oxford School

- Highland Park Junior High

- Joseph Howe Elementary School

- Nova Scotia Community College (Institute of Technology Campus)

- Shambhala School

- St. Joseph's-Alexander McKay Elementary School

- St. Stephen's Elementary School

Community facilities

- Bloomfield Centre

- Centennial Pool

- Citadel Community Centre

- Devonshire Arena

- George Dixon Centre

- Halifax North Memorial Library

- Needham Centre

- Needham Pool

Notes

- 1 2 Silver, Jim (February 2008). Public Housing Risks and Alternatives: Uniacke Square in North End Halifax (PDF). Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9780886275877.

- ↑ Melles, Bruktawit B. (March 2003). "The Relationship Between Policy, Planning and Neighbourhood Change: The Case of the Gottingen Street Neighbourhood, 1950-2000" (PDF). School of Architecture and Planning, Dalhousie University.

- ↑ Beed, Blair. "History - Saint Patrick's Parish". St. Patrick's Church. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ↑ "Halifax Armoury". Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ↑ "Jubilation as Halifax Shipyard awarded contract". CBC News. 19 October 2011.

- 1 2 Taber, Jane (21 August 2013). "Irving ramps up for Halifax Shipyard contract". The Globe and Mail.

- ↑ Halifax

- ↑ Bloomfield Centre

- ↑ North By North End

- ↑ Grainery Food Co-Op

- ↑ Anchor Archive Zine Library

- ↑ North End Community Gardening Association

- ↑ Bloomfield Centre Master Plan – Draft Report

Further reading

- Paul A. Erickson, Halifax's North End: An anthropologist looks at the city, Hantsport: Lancelot Press, 1987.

External links

| ||||||

Coordinates: 44°39′47.3″N 63°36′4.6″W / 44.663139°N 63.601278°W