Normal number

In mathematics, a normal number is a real number whose infinite sequence of digits in every base b[1] is distributed uniformly in the sense that each of the b digit values has the same natural density 1/b, also all possible b2 pairs of digits are equally likely with density b−2, all b3 triplets of digits equally likely with density b−3, etc.

Intuitively this means that no digit, or (finite) combination of digits, occurs more frequently than any other, and this is true whether the number is written in base 10, binary, or any other base. A normal number can be thought of as an infinite sequence of coin flips (binary) or rolls of a die (base 6). Even though there will be sequences such as 10, 100, or more consecutive tails (binary) or fives (base 6) or even 10, 100, or more repetitions of a sequence such as tail-head (two consecutive coin flips) or 6-1 (two consecutive rolls of a die), there will also be equally many of any other sequence of equal length. No digit or sequence is "favored".

While a general proof can be given that almost all real numbers are normal (in the sense that the set of exceptions has Lebesgue measure zero), this proof is not constructive and only very few specific numbers have been shown to be normal. For example, it is widely believed that the numbers √2, π, and e are normal, but a proof remains elusive.

Definitions

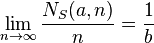

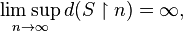

Let Σ be a finite alphabet of b digits, and Σ∞ the set of all sequences that may be drawn from that alphabet. Let S ∈ Σ∞ be such a sequence. For each a in Σ let NS(a, n) denote the number of times the letter a appears in the first n digits of the sequence S. We say that S is simply normal if the limit

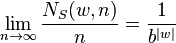

for each a. Now let w be any finite string in Σ∗ and let NS(w, n) to be the number of times the string w appears as a substring in the first n digits of the sequence S. (For instance, if S = 01010101..., then NS(010, 8) = 3.) S is normal if, for all finite strings w ∈ Σ∗,

where | w | denotes the length of the string w. In other words, S is normal if all strings of equal length occur with equal asymptotic frequency. For example, in a normal binary sequence (a sequence over the alphabet {0,1}), 0 and 1 each occur with frequency 1⁄2; 00, 01, 10, and 11 each occur with frequency 1⁄4; 000, 001, 010, 011, 100, 101, 110, and 111 each occur with frequency 1⁄8, etc. Roughly speaking, the probability of finding the string w in any given position in S is precisely that expected if the sequence had been produced at random.

Suppose now that b is an integer greater than 1 and x is a real number. Consider the infinite digit sequence expansion Sx, b of x in the base b positional number system (we ignore the decimal point). We say that x is simply normal in base b if the sequence Sx, b is simply normal[2] and that x is normal in base b if the sequence Sx, b is normal.[3] The number x is called a normal number (or sometimes an absolutely normal number) if it is normal in base b for every integer b greater than 1.[4][5]

A given infinite sequence is either normal or not normal, whereas a real number, having a different base-b expansion for each integer b ≥ 2, may be normal in one base but not in another.[6][7] For bases r and s with log r / log s rational (so that r = bm and s = bn) every number normal in base r is normal in base s. For bases r and s with log r / log s irrational, there are uncountably many numbers normal in each base but not the other.[7]

A disjunctive sequence is a sequence in which every finite string appears. A normal sequence is disjunctive, but a disjunctive sequence need not be normal. A rich number in base b is one whose expansion in base b is disjunctive:[8] one that is disjunctive to every base is called absolutely disjunctive or is said to be a lexicon. A number normal in base b is rich in base b, but not necessarily conversely. The real number x is rich in base b if and only if the set { x bn mod 1: n∈N } is dense in the unit interval.[8][9]

We defined a number to be simply normal in base b if each individual digit appears with frequency 1/b. For a given base b, a number can be simply normal (but not normal or b-dense), b-dense (but not simply normal or normal), normal (and thus simply normal and b-dense), or none of these. A number is absolutely non-normal or absolutely abnormal if it is not simply normal in any base.[4][10]

Properties and examples

The concept of a normal number was introduced by Émile Borel in 1909. Using the Borel–Cantelli lemma, he proved the normal number theorem: almost all real numbers are normal, in the sense that the set of non-normal numbers has Lebesgue measure zero (Borel 1909). This theorem established the existence of normal numbers. In 1917, Wacław Sierpiński showed that it is possible to specify a particular such number. Becher and Figueira proved in 2002 that there is a computable absolutely normal number, however no digits of their number are known.

The set of non-normal numbers, though "small" in the sense of being a null set, is "large" in the sense of being uncountable. For instance, there are uncountably many numbers whose decimal expansion does not contain the digit 5, and none of these are normal.

- 0.1234567891011121314151617...,

obtained by concatenating the decimal representations of the natural numbers in order, is normal in base 10, but it might not be normal in some other bases.

- 0.235711131719232931374143...,

obtained by concatenating the prime numbers in base 10, is normal in base 10, as proved by Copeland and Erdős (1946). More generally, the latter authors proved that the real number represented in base b by the concatenation

- 0.f(1)f(2)f(3)...,

where f(n) is the nth prime expressed in base b, is normal in base b. Besicovitch (1935) proved that the number represented by the same expression, with f(n) = n2,

- 0.149162536496481100121144...,

obtained by concatenating the square numbers in base 10, is normal in base 10. Davenport & Erdős (1952) proved that the number represented by the same expression, with f being any polynomial whose values on the positive integers are positive integers, expressed in base 10, is normal in base 10.

Nakai & Shiokawa (1992) proved that if f(x) is any non-constant polynomial with real coefficients such that f(x) > 0 for all x > 0, then the real number represented by the concatenation

- 0.[f(1)][f(2)][f(3)]...,

where [f(n)] is the integer part of f(n) expressed in base b, is normal in base b. (This result includes as special cases all of the above-mentioned results of Champernowne, Besicovitch, and Davenport & Erdős.) The authors also show that the same result holds even more generally when f is any function of the form

- f(x) = α·xβ + α1·xβ1 + ... + αd·xβd,

where the αs and βs are real numbers with β > β1 > β2 > ... > βd ≥ 0, and f(x) > 0 for all x > 0.

Every Chaitin's constant  is a normal number (Calude, 1994).

A computable normal number was constructed in (Becher 2002). Although these constructions do not directly give the digits of the numbers constructed, the second shows that it is possible in principle to enumerate all the digits of a particular normal number.

is a normal number (Calude, 1994).

A computable normal number was constructed in (Becher 2002). Although these constructions do not directly give the digits of the numbers constructed, the second shows that it is possible in principle to enumerate all the digits of a particular normal number.

Bailey and Crandall show an explicit uncountably infinite class of b-normal numbers by perturbing Stoneham numbers.[11]

It has been an elusive goal to prove the normality of numbers which were not explicitly constructed for the purpose. It is for instance unknown whether √2, π, ln(2) or e is normal (but all of them are strongly conjectured to be normal, because of some empirical evidence ). It is not even known whether all digits occur infinitely often in the decimal expansions of those constants. In particular, the popular claim "every string of numbers eventually occurs in π" is not known to be true. It has been conjectured that every irrational algebraic number is normal; while no counterexamples are known, there also exists no algebraic number that has been proven to be normal in any base.

Non-normal numbers

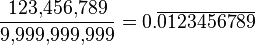

No rational number is normal to any base, since the digit sequences of rational numbers are eventually periodic.[12] (However, a rational number can be simply normal to a particular base:  is simply normal to base 10.)

is simply normal to base 10.)

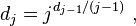

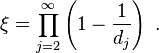

Martin 2001 has given a simple example of an irrational absolutely non-normal number.[13] Let d2 = 4 and

Then ξ is absolutely non-normal and a Liouville number; hence a transcendental number.

Properties

Additional properties of normal numbers include:

- Every positive number x is the product of two normal numbers. For instance if y is chosen uniformly at random from the interval (0,1) then almost surely y and x/y are both normal, and their product is x.

- If x is normal in base b and q ≠ 0 is a rational number, then

is normal in base b. (Wall 1949)

is normal in base b. (Wall 1949)

- If

is dense (for every

is dense (for every  and for all sufficiently large n,

and for all sufficiently large n,  ) and

) and  are the base-b expansions of the elements of A, then the number

are the base-b expansions of the elements of A, then the number  , formed by concatenating the elements of A, is normal in base b (Copeland and Erdős 1946). From this it follows that Champernowne's number is normal in base 10 (since the set of all positive integers is obviously dense) and that the Copeland–Erdős constant is normal in base 10 (since the prime number theorem implies that the set of primes is dense).

, formed by concatenating the elements of A, is normal in base b (Copeland and Erdős 1946). From this it follows that Champernowne's number is normal in base 10 (since the set of all positive integers is obviously dense) and that the Copeland–Erdős constant is normal in base 10 (since the prime number theorem implies that the set of primes is dense).

- A sequence is normal if and only if every block of equal length appears with equal frequency. (A block of length k is a substring of length k appearing at a position in the sequence that is a multiple of k: e.g. the first length-k block in S is S[1..k], the second length-k block is S[k+1..2k], etc.) This was implicit in the work of Ziv and Lempel (1978) and made explicit in the work of Bourke, Hitchcock, and Vinodchandran (2005).

- A number is normal in base b if and only if it is simply normal in base bk for every integer

. This follows from the previous block characterization of normality: Since the nth block of length k in its base b expansion corresponds to the nth digit in its base bk expansion, a number is simply normal in base bk if and only if blocks of length k appear in its base b expansion with equal frequency.

. This follows from the previous block characterization of normality: Since the nth block of length k in its base b expansion corresponds to the nth digit in its base bk expansion, a number is simply normal in base bk if and only if blocks of length k appear in its base b expansion with equal frequency.

- A number is normal if and only if it is simply normal in every base. This follows from the previous characterization of base b normality.

- A number is b-normal if and only if there exists a set of positive integers

where the number is simply normal to bases bm for all

where the number is simply normal to bases bm for all  [14] No finite set suffices to show that the number is b-normal.

[14] No finite set suffices to show that the number is b-normal.

- The set of normal sequences is closed under finite variations: adding, removing, or changing a finite number of digits in any normal sequence leaves it normal.

Connection to finite-state machines

Agafonov showed an early connection between finite-state machines and normal sequences: every infinite subsequence selected from a normal sequence by a regular language is also normal. In other words, if one runs a finite-state machine on a normal sequence, where each of the finite-state machine's states are labeled either "output" or "no output", and the machine outputs the digit it reads next after entering an "output" state, but does not output the next digit after entering a "no output state", then the sequence it outputs will be normal (Agafonov 1968).

A deeper connection exists with finite-state gamblers (FSGs) and information lossless finite-state compressors (ILFSCs).

- A finite-state gambler (a.k.a. finite-state martingale) is a finite-state machine over a finite alphabet

, each of whose states is labelled with percentages of money to bet on each digit in

, each of whose states is labelled with percentages of money to bet on each digit in  . For instance, for an FSG over the binary alphabet

. For instance, for an FSG over the binary alphabet  , the current state q bets some percentage

, the current state q bets some percentage ![q_0 \in [0,1]](../I/m/5755fa1403a21fc2db76ee18a5a65155.png) of the gambler's money on the bit 0, and the remaining

of the gambler's money on the bit 0, and the remaining  fraction of the gambler's money on the bit 1. The money bet on the digit that comes next in the input (total money times percent bet) is multiplied by

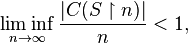

fraction of the gambler's money on the bit 1. The money bet on the digit that comes next in the input (total money times percent bet) is multiplied by  , and the rest of the money is lost. After the bit is read, the FSG transitions to the next state according to the input it received. A FSG d succeeds on an infinite sequence S if, starting from $1, it makes unbounded money betting on the sequence; i.e., if

, and the rest of the money is lost. After the bit is read, the FSG transitions to the next state according to the input it received. A FSG d succeeds on an infinite sequence S if, starting from $1, it makes unbounded money betting on the sequence; i.e., if

- where

is the amount of money the gambler d has after reading the first n digits of S (see limit superior).

is the amount of money the gambler d has after reading the first n digits of S (see limit superior).

- A finite-state compressor is a finite-state machine with output strings labelling its state transitions, including possibly the empty string. (Since one digit is read from the input sequence for each state transition, it is necessary to be able to output the empty string in order to achieve any compression at all). An information lossless finite-state compressor is a finite-state compressor whose input can be uniquely recovered from its output and final state. In other words, for a finite-state compressor C with state set Q, C is information lossless if the function

, mapping the input string of C to the output string and final state of C, is 1–1. Compression techniques such as Huffman coding or Shannon–Fano coding can be implemented with ILFSCs. An ILFSC C compresses an infinite sequence S if

, mapping the input string of C to the output string and final state of C, is 1–1. Compression techniques such as Huffman coding or Shannon–Fano coding can be implemented with ILFSCs. An ILFSC C compresses an infinite sequence S if

- where

is the number of digits output by C after reading the first n digits of S. Note that the compression ratio (the limit inferior above) can always be made to equal 1 by the 1-state ILFSC that simply copies its input to the output.

is the number of digits output by C after reading the first n digits of S. Note that the compression ratio (the limit inferior above) can always be made to equal 1 by the 1-state ILFSC that simply copies its input to the output.

Schnorr and Stimm showed that no FSG can succeed on any normal sequence, and Bourke, Hitchcock and Vinodchandran showed the converse. Therefore:

- A sequence is normal if and only if there is no finite-state gambler that succeeds on it.

Ziv and Lempel showed:

- A sequence is normal if and only if it is incompressible by any information lossless finite-state compressor

(they actually showed that the sequence's optimal compression ratio over all ILFSCs is exactly its entropy rate, a quantitative measure of its deviation from normality, which is 1 exactly when the sequence is normal). Since the LZ compression algorithm compresses asymptotically as well as any ILFSC, this means that the LZ compression algorithm can compress any non-normal sequence. (Ziv Lempel 1978)

These characterizations of normal sequences can be interpreted to mean that "normal" = "finite-state random"; i.e., the normal sequences are precisely those that appear random to any finite-state machine. Compare this with the algorithmically random sequences, which are those infinite sequences that appear random to any algorithm (and in fact have similar gambling and compression characterizations with Turing machines replacing finite-state machines).

Connection to equidistributed sequences

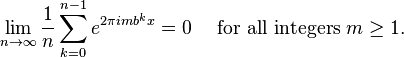

A number x is normal in base b if and only if the sequence  is equidistributed modulo 1,[15][16] or equivalently, using Weyl's criterion, if and only if

is equidistributed modulo 1,[15][16] or equivalently, using Weyl's criterion, if and only if

This connection leads to the terminology that x is normal in base β for any real number β if the sequence  is equidistributed modulo 1.[16]

is equidistributed modulo 1.[16]

Notes

- ↑ The only bases considered here are natural numbers greater than 1

- ↑ Bugeaud 2012, p. 78

- ↑ Bugeaud 2012, p. 79

- 1 2 Bugeaud 2012, p. 102

- ↑ Adamczewski & Bugeaud 2010, p. 413

- ↑ Cassels 1959

- 1 2 Schmidt 1960

- 1 2 Bugeaud 2012, p. 92

- ↑ x bn mod 1 denotes the fractional part of x bn.

- ↑ Martin (2001)

- ↑ Bailey & Crandall (2002).

- ↑ Murty (2007, p. 483).

- ↑ Bugeaud (2012) p.113

- ↑ Long (1957).

- ↑ Bugeaud 2012, p. 89

- 1 2 Everest et al. 2003, p. 127

See also

- Champernowne constant

- De Bruijn sequence

- Infinite monkey theorem

- The Library of Babel

- Illegal number

References

- Adamczewski, Boris; Bugeaud, Yann (2010), "8. Transcendence and diophantine approximation", in Berthé, Valérie; Rigo, Michael, Combinatorics, automata, and number theory, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications 135, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 410–451, ISBN 978-0-521-51597-9, Zbl 1271.11073

- Agafonov, V. N. (1968), "Normal sequences and finite automata", Soviet Mathematics Doklady 9: 324–325, Zbl 0242.94040.

- Bailey, D. H.; Crandall, R. E. (2001), "On the random character of fundamental constant expansions" (PDF), Experimental Mathematics 10: 175–190, doi:10.1080/10586458.2001.10504441.

- Bailey, D. H.; Crandall, R. E. (2002), "Random generators and normal numbers" (PDF), Experimental Mathematics 11 (4): 527–546, doi:10.1080/10586458.2002.10504704.

- Bailey, D. H.; Misiurewicz, M. (2006), "A strong hot spot theorem", Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 134 (9): 2495–2501, doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-06-08551-0.

- Becher, V.; Figueira, S. (2002), "An example of a computable absolutely normal number", Theoretical Computer Science 270: 947–958, doi:10.1016/S0304-3975(01)00170-0.

- Besicovitch, A. S. (1935), "The asymptotic distribution of the numerals in the decimal representation of the squares of the natural numbers", Mathematische Zeitschrift 39: 146–156, doi:10.1007/BF01201350.

- Borel, E. (1909), "Les probabilités dénombrables et leurs applications arithmétiques", Rendiconti del Circolo Matematico di Palermo 27: 247–271, doi:10.1007/BF03019651.

- Bourke, C.; Hitchcock, J. M.; Vinodchandran, N. V. (2005), "Entropy rates and finite-state dimension", Theoretical Computer Science 349 (3): 392–406, doi:10.1016/j.tcs.2005.09.040.

- Bugeaud, Yann (2012), Distribution modulo one and Diophantine approximation, Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics 193, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-11169-0, Zbl pre06066616

- Calude, C. (1994), "Borel normality and algorithmic randomness", in Rozenberg, G.; Salomaa, Arto, Developments in Language Theory: At the Crossroads of Mathematics, Computer Science and Biology, World Scientific, Singapore, pp. 113–119.

- Calude, C.S.; Zamfirescu, T. (1999), "Most numbers obey no probability laws", Publicationes Mathematicae Debrecen 54 (Supplement): 619–623.

- Cassels, J. W. S. (1959), "On a problem of Steinhaus about normal numbers", Colloquium Mathematicum 7: 95–101.

- Champernowne, D. G. (1933), "The construction of decimals normal in the scale of ten", Journal of the London Mathematical Society 8 (4): 254–260, doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-8.4.254.

- Copeland, A. H.; Erdős, P. (1946), "Note on normal numbers", Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 52 (10): 857–860, doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1946-08657-7.

- Dajani, Karma; Kraaikamp, Cor (2002), Ergodic theory of numbers, Carus Mathematical Monographs 29, Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America, ISBN 0-88385-034-6, Zbl 1033.11040.

- Davenport, H.; Erdős, P. (1952), "Note on normal decimals", Canadian Journal of Mathematics 4: 58–63, doi:10.4153/CJM-1952-005-3.

- Everest, Graham; van der Poorten, Alf; Shparlinski, Igor; Ward, Thomas (2003), Recurrence sequences, Mathematical Surveys and Monographs 104, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 0-8218-3387-1, Zbl 1033.11006.

- Khoshnevisan, Davar (2006), "Normal numbers are normal" (PDF), Clay Mathematics Institute Annual Report 2006: 15, continued pp. 27–31.

- Long, C. T. (1957), "Note on normal numbers", Pacific Journal of Mathematics 7 (2): 1163–1165, doi:10.2140/pjm.1957.7.1163, Zbl 0080.03604.

- Martin, Greg (2001), "Absolutely abnormal numbers", American Mathematical Monthly 108: 746–754, doi:10.2307/2695618, Zbl 1036.11035

- Murty, Maruti Ram (2007), Problems in analytic number theory (2 ed.), Springer, ISBN 0-387-72349-8.

- Nakai, Y.; Shiokawa, I. (1992), "Discrepancy estimates for a class of normal numbers", Acta Arithmetica 62 (3): 271–284.

- Schmidt, W. (1960), "On normal numbers", Pacific Journal of Mathematics 10: 661–672, doi:10.2140/pjm.1960.10.661.

- Schnorr, C. P.; Stimm, H. (1972), "Endliche Automaten und Zufallsfolgen", Acta Informatica 1 (4): 345–359, doi:10.1007/BF00289514.

- Sierpiński, W. (1917), "Démonstration élémentaire d'un théorème de M. Borel sur les nombres absolutment normaux et détermination effective d'un tel nombre", Bulletin de la Société Mathématique de France 45: 125–144.

- Wall, D. D. (1949), Normal Numbers, Ph.D. thesis, Berkeley, California: University of California.

- Ziv, J.; Lempel, A. (1978), "Compression of individual sequences via variable-rate coding", IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 24 (5): 530–536, doi:10.1109/TIT.1978.1055934.

Further reading

- Harman, Glyn (2002), "One hundred years of normal numbers", in Bennett, M. A.; Berndt, B.C.; Boston, N.; Diamond, H.G.; Hildebrand, A.J.; Philipp, W., Surveys in number theory: Papers from the millennial conference on number theory, Natick, MA: A K Peters, pp. 57–74, ISBN 1-56881-162-4, Zbl 1062.11052

- Quéfflec, Martine (2006), "Old and new results on normality", in Denteneer, Dee; den Hollander, F.; Verbitskiy, E., Dynamics & Stochastics: Festschrift in honor of M. S. Keane, IMS Lecture Notes – Monograph Series 48, Beachwood, Ohio: Institute of Mathematical Statistics, pp. 225–236, arXiv:math.DS/0608249, doi:10.1214/074921706000000248, ISBN 0-940600-64-1, Zbl 1130.11041