Nonlinear Dirac equation

- See Ricci calculus and Van der Waerden notation for the notation.

| Quantum field theory |

|---|

Feynman diagram |

| History |

|

Incomplete theories |

|

Scientists

|

In quantum field theory, the nonlinear Dirac equation is a model of self-interacting Dirac fermions. This model is widely considered in quantum physics as a toy model of self-interacting electrons.[1][2][3][4][5]

The nonlinear Dirac equation appears in the Einstein-Cartan-Sciama-Kibble theory of gravity, which extends general relativity to matter with intrinsic angular momentum (spin).[6][7] This theory removes a constraint of the symmetry of the affine connection and treats its antisymmetric part, the torsion tensor, as a variable in varying the action. In the resulting field equations, the torsion tensor is a homogeneous, linear function of the spin tensor. The minimal coupling between torsion and Dirac spinors thus generates an axial-axial, spin–spin interaction in fermionic matter, which becomes significant only at extremely high densities. Consequently, the Dirac equation becomes nonlinear (cubic) in the spinor field,[8][9] which causes fermions to be spatially extended and may remove the ultraviolet divergence in quantum field theory.[10]

Models

Two common examples are the massive Thirring model and the Soler model.

Thirring model

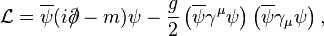

The Thirring model[11] was originally formulated as a model in (1 + 1) space-time dimensions and is characterized by the Lagrangian density

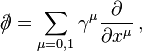

where ψ ∈ ℂ2 is the spinor field, ψ = ψ*γ0 is the Dirac adjoint spinor,

(Feynman slash notation is used), g is the coupling constant, m is the mass, and γμ are the two-dimensional gamma matrices, finally μ = 0, 1 is an index.

Soler model

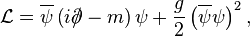

The Soler model[12] was originally formulated in (3 + 1) space-time dimensions. It is characterized by the Lagrangian density

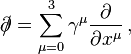

using the same notations above, except

is now the four-gradient operator contracted with the four-dimensional Dirac gamma matrices γμ, so therein μ = 0, 1, 2, 3.

Einstein-Cartan theory

The Lagrangian density for a Dirac spinor field is given by ( )

)

where

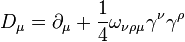

is the Fock-Ivanenko covariant derivative of a spinor with respect to the affine connection,  is the spin connection,

is the spin connection,  is the determinant of the metric tensor

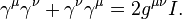

is the determinant of the metric tensor  , and the Dirac matrices satisfy

, and the Dirac matrices satisfy

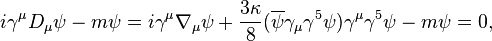

The resulting Dirac equation is

where  is the general-relativistic covariant derivative of a spinor. The cubic term in this equation becomes significant at densities on the order of

is the general-relativistic covariant derivative of a spinor. The cubic term in this equation becomes significant at densities on the order of  .

.

See also

- Dirac equation

- Dirac equation in the algebra of physical space

- Gross-Neveu model

- Higher-dimensional gamma matrices

- Nonlinear Schrödinger equation

- Soler model

- Thirring model

References

- ↑ D.D. Ivanenko (1938). "Notes to the theory of interaction via particles". Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 8: 260–266.

- ↑ R. Finkelstein, R. LeLevier, and M. Ruderman (1951). "Nonlinear spinor fields". Phys. Rev. 83: 326–332. Bibcode:1951PhRv...83..326F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.83.326.

- ↑ R. Finkelstein, C. Fronsdal, and P. Kaus (1956). "Nonlinear Spinor Field". Phys. Rev. 103 (5): 1571–1579. Bibcode:1956PhRv..103.1571F. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.103.1571.

- ↑ W. Heisenberg (1957). "Quantum Theory of Fields and Elementary Particles". Rev. Mod. Phys. 29 (3): 269–278. Bibcode:1957RvMP...29..269H. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.29.269.

- ↑ Gross, David J. and Neveu, André (1974). "Dynamical symmetry breaking in asymptotically free field theories". Phys. Rev. D 10 (10): 3235–3253. Bibcode:1974PhRvD..10.3235G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.10.3235.

- ↑ Dennis W. Sciama, "The physical structure of general relativity". Rev. Mod. Phys. 36, 463-469 (1964).

- ↑ Tom W. B. Kibble, "Lorentz invariance and the gravitational field". J. Math. Phys. 2, 212-221 (1961).

- ↑ F. W. Hehl and B. K. Datta (1971). "Nonlinear spinor equation and asymmetric connection in general relativity". J. Math. Phys. 12: 1334–1339. Bibcode:1971JMP....12.1334H. doi:10.1063/1.1665738.

- ↑ Friedrich W. Hehl, Paul von der Heyde, G. David Kerlick, and James M. Nester (1976). "General relativity with spin and torsion: Foundations and prospects". Rev. Mod. Phys. 48: 393–416. Bibcode:1976RvMP...48..393H. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.48.393.

- ↑ Nikodem J. Popławski (2010). "Nonsingular Dirac particles in spacetime with torsion". Phys. Lett. B 690: 73–77. arXiv:0910.1181. Bibcode:2010PhLB..690...73P. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2010.04.073.

- ↑ Walter Thirring (1958). "A soluble relativistic field theory". Annals of Physics 3 (1): 91–112. Bibcode:1958AnPhy...3...91T. doi:10.1016/0003-4916(58)90015-0.

- ↑ Mario Soler (1970). "Classical, Stable, Nonlinear Spinor Field with Positive Rest Energy". Phys. Rev. D 1 (10): 2766–2769. Bibcode:1970PhRvD...1.2766S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.1.2766.