Nicolas Flamel

| Nicolas Flamel | |

|---|---|

Flamel as represented in 1402 on the portal of Sainte-Geneviève des Ardens (From Étienne François Villain, 1761) | |

| Born |

c. 1330 Pontoise |

| Died |

March 22, 1418 Paris, France |

Nicolas Flamel (French: [nikɔla flamɛl]; prob. Pontoise, ca 1330 – Paris, March 22, 1418)[1] was a successful French scribe and manuscript-seller. After his death, Flamel developed a reputation as an alchemist believed to have discovered the Philosopher's Stone and achieved immortality. These legendary accounts only appeared in the seventeenth century.

According to texts ascribed to Flamel almost two hundred years after his death, he had learned alchemical secrets from a Jewish converso on the road to Santiago de Compostela. As Deborah Harkness put it, "Others thought Flamel was the creation of 17th-century editors and publishers desperate to produce modern printed editions of supposedly ancient alchemical treatises then circulating in manuscript for an avid reading public."[2] He has since appeared as a legendary alchemist in various fictional works.

Life

The historical Flamel lived in Paris in the fourteenth and fifteenth century and his life is one of the best documented in the history of medieval alchemy.[3] He ran two shops as a scribe and married Perenelle in 1368. She brought the wealth of two previous husbands to the marriage. The French Catholic couple owned several properties, and contributed financially to churches, sometimes by commissioning sculptures.[4] Later in life they were noted for their wealth and philanthropy.

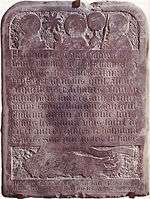

Flamel lived into his 80s, and in 1410 designed his own tombstone, which was carved with the images of Christ, St. Peter, and St. Paul. The tombstone is preserved at the Musée de Cluny in Paris. Records show that Flamel died in 1418.[5] He was buried in Paris at the Musée de Cluny at the end of the nave of the former Church of Saint-Jacques-de-la-Boucherie.[6] His will, dated 22 November 1416, indicates that he was generous but that he did not have the extraordinary wealth of later alchemical legend. There is no indication that the real Flamel of history was involved in alchemy, pharmacy or medicine.[3]

"Flamel was a real person, and he may have dabbled in alchemy, but his reputation as an author and immortal adept must be accepted as an invention of the seventeenth century."[3]

Nicolas Flamel in Paris

One of Flamel's houses still stands in Paris, at 51 rue de Montmorency. It is the oldest stone house in the city.[7] There is an old inscription on the wall: "We, ploughmen and women living at the porch of this house, built in 1407, are requested to say every day an 'Our Father' and an 'Ave Maria' praying God that His grace forgive poor and dead sinners." The ground floor currently contains a restaurant.[8] A Paris street near the Louvre Museum, the rue Nicolas Flamel, has been named after him; it intersects with the rue Pernelle, named after his wife.[8]

-

The house of Flamel in Paris, now a restaurant.

-

A closer shot of the Auberge Nicolas Flamel, June, 2008.

-

Rue Nicolas Flamel street sign in Paris

-

Plaque on home

Posthumous reputation as an alchemist

Legendary accounts of Flamel's life are based on seventeenth century works, primarily Livre des figures hiéroglyphiques. The essence of his reputation are claims that he succeeded at the two goals of alchemy: that he made the Philosopher's Stone, which turns base metals into gold, and that he and his wife Perenelle achieved immortality through the "Elixir of Life".

An alchemical book, published in Paris in 1612 as Livre des figures hiéroglyphiques and in London in 1624 as Exposition of the Hieroglyphical Figures was attributed to Flamel.[9] It is a collection of designs purportedly commissioned by Flamel for a tympanum at the Cimetière des Innocents in Paris, long disappeared at the time the work was published. In the publisher's introduction Flamel's search for the Philosopher's Stone was described. According to that introduction, Flamel had made it his life's work to understand the text of a mysterious 21-page book he had purchased. The introduction claims that, around 1378, he travelled to Spain for assistance with translation. On the way back, he reported that he met a sage, who identified Flamel's book as being a copy of the original Book of Abramelin the Mage. With this knowledge, over the next few years, Flamel and his wife allegedly decoded enough of the book to successfully replicate its recipe for the Philosopher's Stone, producing first silver in 1382, and then gold. In addition, Flamel is said to have studied some texts in Hebrew.

The validity of this story was first questioned in 1761 by Etienne Villain. He claimed that the source of the Flamel legend was P. Arnauld de la Chevalerie, publisher of Exposition of the Hieroglyphical Figures, who wrote the book under the pseudonym Eiranaeus Orandus.[10] Other writers have defended the legendary account of Flamel’s life, which has been embellished by stories of sightings in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and expanded in fictitious works ever since.

Flamel had achieved legendary status within the circles of alchemy by the mid 17th Century, with references in Isaac Newton's journals to "the Caduceus, the Dragons of Flammel".[11] Interest in Flamel revived in the 19th century; Victor Hugo mentioned him in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Erik Satie was intrigued by Flamel,[12] and Albert Pike makes reference to Nicholas Flamel in his book Morals and Dogma of the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry. Flamel's reputation as an alchemist was further bolstered in the late 20th Century by his depiction as the creator of the eponymous alchemical substance in the best-selling novel Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone.[13]

Works ascribed to Flamel

- Le Livre des figures hiéroglyphiques (The Book of hieroglyphic figures), first published in Trois traictez de la philosophie naturelle, Paris, Veuve Guillemot, 1612

- Le sommaire philosophique (The Philosophical summary), first published in De la transformation métallique, Paris, Guillaume Guillard, 1561

- Le Livre des laveures (The Book of washing), manuscript BnF MS. Français 19978

- Le Bréviaire de Flamel (Flamel's breviary), manuscript BnF MS. Français 14765

In popular culture

- Nicolas Flamel is a main character in Michael Scott's novel series The Secrets of the Immortal Nicholas Flamel (2007-2012).

- Nicolas Flamel is an unseen character in Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone and owner of title of object.

- Nicolas Flamel is mentioned frequently in the 2014 horror film As Above, So Below.

- The historical Nicolas Flamel is mentioned in Dan Brown's novel The DaVinci Code as one of the Grand Masters of the Prieuré de Sion, or Priory of Sion.

- Nicolas Flamel is mentioned in The Librarians episode "And the Horns of a Dilemma" as one of the immortal beings who could be wounded but not killed.

- Nicolas Flamel is mentioned in Assassin's Creed: Unity, in which the protagonist must obtain an alchemical potion said to be crafted by him.

- In Fullmetal Alchemist, the main character and his brother wear a symbol called the Flamel.

Notes

- ↑ According to Nigel Wilkins: Nicolas Flamel, des livres et de l'or, Chapter 3: 'D'arcanes et d'arcades.

- ↑ Harkness, review of Dixon 1994 in Isis 89.1 (1998) p.a 132.

- 1 2 3 Dixon 1994, p. xvii.

- ↑ Dixon 1994, p. xvi.

- ↑ Cohen, Kathleen (1973). Metamorphosis of a death symbol: the transi tomb in the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. University of California Press. p. 98.

- ↑ Hauck, Dennis William (2008). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Alchemy. Penguin.

- ↑ McAuliffe, Mary. Paris Discovered: Explorations in the City of Light. Princeton Book Company, 2006. ISBN 978-0-87127-287-4

- 1 2 Brooke, Anna E. (2008). Frommer's Paris and Disneyland Resort Paris With Your Family: From Captivating Culture to the Magic of Disneyland. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 134. ISBN 9780470714577.

- ↑ Laurinda Dixon, ed., Nicolas Flamel, his Exposition of the Hieroglyphicall Figures (1624) (New York: Garland) 1994.

- ↑ Dixon 1994, p. xiv.

- ↑ Newton, Isaac. "Sententiæ luciferæ et Conclusiones notabiles". Keynes MS 56 (quoted in Westfall, Never at Rest, p. 299). Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- ↑ Wilkins 1993.

- ↑ "Who is Nicholas Flamel? And other historical figures". nlm.nih.gov. United States National Library of Medicine. 24 August 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

References

- Decoding the Past: The Real Sorcerer's Stone, November 15, 2006, History Channel video documentary

- The Philosopher's Stone: A Quest for the Secrets of Alchemy, 2001, Peter Marshall, ISBN 0-330-48910-0

- Creations of Fire, Cathy Cobb & Harold Goldwhite, 2002, ISBN 0-7382-0594-X

- Wilkins, Nigel, Nicolas Flamel- des livres et de l'or, Éditions Imago, 1993, ISBN 2-902702-77-9

- Dixon, Laurinda (1994). Nicolas Flamel. His Exposition of the Hieroglyphicall Figures (1624). Garland Publishing.

External links

- The Alchemy Web Site, alchemical writings ascribed to Flamel.

|