Ngāti Maniapoto

| Ngāti Maniapoto | |

| Iwi of New Zealand | |

|---|---|

| |

| Rohe (location) | Waikato-Waitomo |

| Waka (canoe) | Tainui |

| Population | 33,627 |

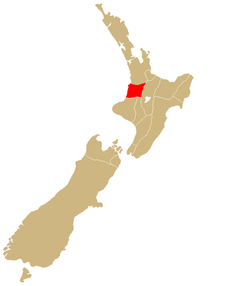

Ngāti Maniapoto is an iwi (tribe) based in the Waikato-Waitomo (flowing water-cave water) region of New Zealand's North Island. It is part of the Tainui (big tide) confederation, the members of which trace their whakapapa (genealogy) back to people who arrived in New Zealand on the waka (canoe) Tainui. The 2006 New Zealand census shows the iwi to have a membership of 33,627 , making it the 7th biggest iwi in New Zealand.

Marae

There are many marae (area in front of a wharenui) in the Ngāti Maniapoto area, one of the notable ones being Te Tokanga Nui A Noho at Te Kuiti (the narrowing) in the King Country. This marae was gifted to Ngāti Maniapoto by Te Kooti, a Rongowhakaata tribesman who sought refuge from the British colonial army during the New Zealand land wars. Of equal significance but less publicly known is Tiroa Pā where the last Io whare wānanga (traditional study centre) was held in a specially crafted whare called Te Miringa Te Kakara. The other whare wānanga was near present-day Piopio and was called Kahuwera. It stood on the hill of the same name and commanded a panoramic view of the Mokau River valley across the Maraetaua block.

History

Ancestors of Ngati Maniapoto conquered Waikato's Ngati Raukawa and drove them from the fertile Otawha (Te Awamutu ) area . The land was not highly valued and some was given away to Ngati Mahuta who chopped down the forest and cultivated the land. About 1830-35 a few acres of land were sold to European settlers. Ngati Maniapoto were jealous and asserted a claim to the land, reoccupying some of it . A feud ensued between the two tribes that verged on open warfare. Most chiefs supported selling land to Europeans as they were desperate to obtain goods such as carts, seeds, trees, ploughs and mills. But friction between the tribes in the same area simmered. 800 acres of land was sold at nearby Rangiowhaia to the government to support an Industrial school run by John Gorst and funded by governor George Grey to train Maori in tailoring, agriculture and repair of industrial goods.[1] The supply of European goods and the support of Europeans gave Waikato Maori far more leisure time. During the first Taranaki war Ngati Maniapoto played an active part and materially benefited by plundering the settlers farms of livestock and equipment. A truce ended this war but Wiremu Kingi from Taranaki and Rewi Maniapoto were both keen to restart the war. Kingi was keen to involve Maniapoto as they lived in a fertile region and had received significant help from missionaries in developing commercial agricultural from the 1830s. By the early 1853 Maniapoto had become rich selling surplus food to Auckland. Between 1853 and 1857 Maniapoto enjoyed a buoyant economy enabling them to travel regularly to Auckland to sell wheat, flour, peaches and potatoes and bring back blankets, shirts, sugar, tobacco and rum. The high prices they received were due to an Australian gold rush which lead to a shortage of flour from Australia. When the gold rush ended in 1857, the prices for Maniapoto produce crashed, leading to a depressed Maniapoto economy. Maniapoto then perceived the low prices as some kind of pakeha trick. It was during this depressed time that Maniapoto developed significant anti-pakeha feelings. This is one of the reasons why Maniapoto were keen to attack Auckland - in 1863 - to gain utu for the low prices and, the pain these low prices had caused Maniapoto. The Maniapoto were very familiar with all the trails leading into Auckland and where all the isolated farmers lived. In 1863 - using their Taranaki experience - the Maniapoto lived in the bush covered hills and descended on isolated farms to rob and kill farmers and their families, especially in the Drury and Runciman area.[2]

After the Waikato war, the three leading Ngāti Maniapoto chiefs of the time, Rewi Manga Maniapoto, Wahanui and Taonui Hikaka, negotiated with the colonial government to allow the main trunk railway line through Ngāti Maniapoto territories. This was done because of word that the Māori King Tāwhiao and Te Kooti were also trying to negotiate with the British colonial government for rail access and to set up Native Land Courts throughout the region. This could have meant that Ngāti Maniapoto would become landless. It is said that when Tāwhiao found out what they had done, he angrily threw his hat onto a survey map of the Ngāti Maniapoto territory and claimed the area where the hat fell as Te Rohe Pōtae, the district of the hat. To day this territory is called the King Country, in reference to this event. Maniapoto said they acknowledged no king but their ancestor Maniapoto "they would trample the words of Tawhaio under their feet". [3]

However, tensions grew between Ngāti Maniapoto chiefs and the King Tāwhiao because of what could be perceived as a transgressions of authority. It was widely understood that chiefs in Ngāti Maniapoto were only answerable to their constituent hapu, although they supported the notion and principles of the Kingitanga, this did not mean they could or even wanted to surrender their rangatiratanga (chieftainship). After all, the King was a king by virtue of the approval of the chiefs. While the King was resident in Ngāti Maniapoto territory as a guest, the mana of Ngāti Maniapoto reigned supreme in their rohe and the King did not have authority over their land.

Famous people

- Dame Kiri Te Kanawa - opera singer

- Temuera Morrison - actor

- Dame Rangimarie Hetet - famous weaver and fabric artist

- Dr Pei Te Hurinui Jones - academic and writer

- Taonui Hikaka - Paramount chief

- Rewi Manga Maniapoto - Warrior Chief

- Wahanui - negotiator

- Tiki Taane - singer

- Richard Kahui - rugby player

- Wiremu Te Awhitu - Catholic Priest.

- Sandor Earl - league player

- Rongo Wetere - educationalist

Hapu

- Ngāti Rora

- Ngāti Hinewai

- Ngāti Taiawa or Taewa

- Ngāti Kaputuhi

- Ngāti Ngutu

- Ngāti Mokau

- Ngāti Rereahu

- Ngāti Hikairo

- Ngāti Apakura

- Ngāti Matakore

- Ngāti Raukawa

- Ngāti Utu

- Ngāti Te Kanawa

- Ngāti Paretekawa

- Ngāti Waiora

- Ngāti Hari

- Ngāti Uekaha

- Ngati Peehi

References

External links

- Maniapoto Trust Board

- Ngati Maniapoto Marae Pact Trust

- Ngāti Maniapoto in Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||