New Zealand wine

New Zealand wine is largely produced in ten major wine growing regions spanning latitudes 36° to 45° South and extending 1,600 kilometres (990 mi). They are, from north to south Northland, Auckland, Waikato/Bay of Plenty, Gisborne, Hawke's Bay, Wellington, Nelson, Marlborough, Canterbury/Waipara and Central Otago.

History

Wine making and vine growing go back to colonial times in New Zealand. British Resident and keen oenologist James Busby was, as early as 1836, attempting to produce wine at his land in Waitangi.[1] In 1851 New Zealand's oldest existing vineyard was established by French Roman Catholic missionaries at Mission Estate in Hawke's Bay.[2] In 1883 William Henry Beetham was recognised as being the first pioneer to plant Pinot Noir and Hermitage (Syrah) grapes in New Zealand at his Lansdowne vineyard in Masterton. In 1895 the expert consultant viticulturist and oenologist Romeo Bragato was invited by the NZ government's department of Agriculture to investigate winemaking possibilities and after tasting Beetham's Hermitage he concluded that the Wairarapa and New Zealand was "pre-eminently suited to viticulture". Beetham was supported in his endeavours by his French wife Marie Zelie Hermance Frere Beetham. Their partnership and innovation to pursue winemaking helped formed the basis of modern New Zealand's viticulture practices.[3] Due to economic (the importance of animal agriculture and the protein export industry), legislative (prohibition and the temperance) and cultural factors (the overwhelming predominance of beer and spirit drinking British immigrants), wine was for many years a marginal activity in terms of economic importance. Dalmatian immigrants arriving in New Zealand at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century brought with them viticultural knowledge and planted vineyards in West and North Auckland. Typically, their vineyards produced sherry and port for the palates of New Zealanders of the time, and table wine for their own community.

The three factors that held back the development of the industry simultaneously underwent subtle but historic changes in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In 1973, Britain entered the European Economic Community, which required the ending of historic trade terms for New Zealand meat and dairy products. This led ultimately to a dramatic restructuring of the agricultural economy. Before this restructuring was fully implemented, diversification away from traditional protein products to products with potentially higher economic returns was explored. Vines, which produce best in low moisture and low soil fertility environments, were seen as suitable for areas that had previously been marginal pasture. The end of the 1960s saw the end of the New Zealand institution of the "six o'clock swill", where pubs were open for only an hour after the end of the working day and closed all Sunday. The same legislative reform saw the introduction of BYO (bring your own) licences for restaurants. This had a profound and unexpected effect on New Zealanders' cultural approach to wine.

Finally the late 1960s and early 1970s saw the rise of the "overseas experience," where young New Zealanders traveled and lived and worked overseas, predominantly in Europe. As a cultural phenomenon, the overseas experience predates the rise of New Zealand's premium wine industry, but by the 1960s a distinctly Kiwi (New Zealand) identity had developed and the passenger jet made the overseas experience possible for a large numbers of New Zealanders who experienced first-hand the premium wine cultures of Europe.

First steps

In the 1970s, Montana in Marlborough started producing wines which were labelled by year of production (vintage) and grape variety (in the style of wine producers in Australia). The first production of a Sauvignon blanc of great note appears to have occurred in 1977. Also produced in that year were superior quality wines of Muller Thurgau, Riesling and Pinotage. The excitement created from these successes and from the early results of Cabernet Sauvignon from Auckland and Hawkes Bay launched the industry with ever increasing investment, leading to more hectares planted, rising land prices and greater local interest and pride. Such was the boom that over-planting occurred, particularly in the "wrong" varietals that fell out of fashion in the early 1980s. In 1984 the then Labour Government paid growers to pull up vines to address a glut that was damaging the industry. Ironically many growers used the Government grant not to restrict planting, but to swap from less economic varieties (such as Müller Thurgau and other hybrids) to more fashionable varieties (Chardonnay and Sauvignon blanc), using the old root stock. The glut was only temporary in any case, as boom times returned swiftly.

Sauvignon blanc breakthrough

New Zealand is home to what many wine critics consider the world’s best Sauvignon blanc. Oz Clarke, a well-known British wine critic wrote in the 1990s that New Zealand Sauvignon blanc was "arguably the best in the world" (Rachman). Historically, Sauvignon blanc has been used in many French regions in both AOC and Vin de Pays wine. The most famous had been France’s Sancerre. It is also the grape used to make Pouilly Fumé. Following Robert Mondavi's lead in renaming Californian Sauvignon blanc Fumé Blanc (partially in reference to Pouilly Fumé and partially to denote the smokiness of the wine produced due to flinty soil properties and partial oak barrel ageing) there was a trend for oaked Sauvignon blanc in New Zealand during the late 1980s. Later the fashion for strong oaky overtones and also the name waned. In the 1980s, wineries in New Zealand, especially in the Marlborough region, began producing outstanding, some critics said unforgettable, Sauvignon blanc. "New Zealand Sauvignon blanc is like a child who inherits the best of both parents—exotic aromas found in certain Sauvignon blancs from the New World and the pungency and limy acidity of an Old World Sauvignon blanc like Sancerre from the Loire Valley" (Oldman, p. 152). One critic said that drinking one's first New Zealand Sauvignon blanc was like having sex for the first time (Taber, p. 244). "No other region in the world can match Marlborough, the northeastern corner of New Zealand's South Island, which seems to be the best place in the world to grow Sauvignon blanc grapes" (Taber, p. 244).

Climate and soil

Wine regions are mostly located in free draining alluvial valleys (Hawke's Bay, Martinborough, Nelson, the Wairau and Awatere valleys of Marlborough, and Canterbury) with notable exceptions (Waiheke Island, Kawarau Gorge in Central Otago). The alluvial deposits are typically the local sandstone called greywacke, which makes up much of the mountainous spine of New Zealand.

Sometimes the alluvial nature of the soil is important, as in Hawke's Bay where the deposits known as the Gimblett Gravels represent such quality characteristics that they are often mentioned on the wine label. The Gimblett Gravels is an area of former river bed with very stoney soils. The effect of the stones is to lower fertility, lower the water table, and act as a heat store that tempers the cool sea breezes that Hawke's Bay experiences. This creates a significantly warmer meso-climate.

Another soil type is represented in Waipara, Canterbury. Here there are the Omihi Hills which are part of the Torlesse group of limestone deposits. Viticulturalists have planted Pinot noir here due to French experience of the affinity between the grape type and the chalky soil on the Côte-d'Or. Even the greywacke alluvial soils in the Waipara valley floor has a higher calcium carbonate concentration as can be witnessed from the milky water that flows in the Waipara River.

The Kawarau valley has a thin and patchy top soil over a bed rock is schist. Early vineyards blasted holes into the bare rock of north facing slopes with miners caps to provide planting holes for the vines. These conditions necessitate irrigation and make the vines work hard for nutrients. This, low cropping techniques and the thermal effect of the rock produces great intensity for the grapes and subsequent wine.

The wine regions in New Zealand stretch from latitudes 36°S in the north (Northland) (comparable in latitude to Jerez, Spain), to 45°S (Central Otago) in the south (comparable in latitude to Bordeaux, France). The climate in New Zealand is maritime, meaning that the sea moderates the weather producing cooler summers and milder winters than would be expected at similar latitudes in Europe and North America. Maritime climates tend also to demonstrate higher variability with cold snaps possible at any time of the year and warm periods even in the depth of winter. The climate is typically wetter, but wine regions have developed in rain shadows and in the east, on the opposite coast from the prevailing moisture-laden wind. The wine regions of New Zealand tend to experience cool nights even in the hottest of summers. The effect of consistently cool nights is to produce fruit which is nearly always high in acidity.

Industry structure and production methods

New Zealand's winemakers employ a variety of production techniques. The traditional concept of a vineyard, where grapes are grown on the land surrounding a central simply owned or family-owned estate with its own discrete viticultural and winemaking equipment and storage, is only one model. While the European cooperative model (where district or AOC village wine-making takes place in a centralized production facility) is uncommon, contract growing of fruit for winemakers has been a feature of the New Zealand industry since the start of the winemaking boom in the 1970s. Indeed, a number of well known producers started out as contract growers.

Many fledgling producers started out using contract fruit while waiting for their own vines to mature enough to produce production-quality fruit. Some producers use contract fruit to supplement the range of varieties they market, even using fruit from other geographical regions. It is common to see, for example, an Auckland producer market a "Marlborough Sauvignon blanc" or a Marlborough producer market a "Gisborne Chardonnay". Contract growing is an example of the use of indigenous agro-industrial methods that predate the New Zealand wine industry.

Another example of the adaptation of NZ methods toward the new industry was the universal use of stainless steel in winemaking adapted from the norms and standards of the New Zealand dairy industry. There was an existing small-scale industrial infrastructure ready for winemakers to economically employ. It should be remembered that while current winemaking technology is almost universally sterile and hygienic worldwide, the natural antibiotic properties of alcohol production were more heavily relied upon in the 1970s when the New Zealand wine industry started.

This pervasive use of stainless steel almost certainly had a distinctive effect on both New Zealand wine styles and the domestic palate. The early wines which made a stir internationally were lauded for the intensity and purity of the fruit in the wine. Indeed, the strength of flavor in the wine favored very dry styles despite intense acidity. While stainless steel did not produce the intensity of fruit, it allowed for its exploitation. Even today, New Zealand white wines tend toward the drier end of the spectrum.

Varieties, styles and directions

Red blends and Bordeaux varieties

New Zealand red wines are typically made from a blend of varietals (Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and much less often Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot and Malbec), or Pinot noir. Recently, in Hawkes Bay, there have been wines made from Syrah, either solely or blends, as well as Tempranillo, Montepulciano and Sangiovese.

Early success in Hawke's Bay in the 1960s by McWilliams, and in the 1980s by Te Mata Estate, led to red wine grape planting and production concentrating on Cabernet Sauvignon by Corbans, McWilliams, and Mission Estate, among many others. As viticultural techniques were improved and tailored to New Zealand's maritime climate, more Merlot and other Bordeaux-style grapes were planted, with quality and quantity increasing. This trend continues and can be seen in the New Zealand Wine Institute statistics indicating that plantings of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Malbec and Syrah now account for 2,496 hectares.

Typically, Bordeaux blends come from regions and sub-regions of New Zealand that are relatively the hottest and driest. 86% of production is centered in Hawke's Bay, with Waiheke Island also producing some notable wines. Wineries that have made a name for Waiheke Island include Stonyridge Larose and Goldwater Estate. Wines that typify the best of Hawkes Bay include Te Mata Estate's Coleraine and Awatea, Craggy Range's Sophia, Newton Forrest Estate's Cornerstone, Esk Valley's The Terraces and Villa Maria's Reserve Merlot and Cabernet. In Marlborough there are also a small number of producers of Bordeaux-style varietal wines.

However, examples of Bordeaux blends can be found as far south as Waipara, in Canterbury where Pegasus Bay's Maestro has demonstrated a drift away from Cabernet Sauvignon predominant blends to Merlot predominant with the addition of Malbec. As can be seen in the hectare plantings statistics, the amount of Cabernet Sauvignon in production has halved since the early part of the century at a time when Sauvignon Blanc has quadrupled and Pinot Noir has doubled. Fashion has turned from Bordeaux blends to Pinot Noir, but it also indicates the marginality of Cabernet Sauvignon in New Zealand conditions.

In general New Zealand red wine tends to be forward and early maturing, fruit-driven and with restrained oak. Hawkes Bay Bordeaux blends have greater body and ageing ability.

Pinot noir

Early in the modern wine industry (late 1970s early 1980s), the comparatively low annual sunshine hours to be found in NZ discouraged the planting of red varieties. But even at this time great hopes were had for Pinot noir (see Romeo Bragato). Initial results were not promising for several reasons, including the mistaken planting of Gamay and the limited number of Pinot noir clones available for planting. One notable exception was the St Helena 1984 Pinot noir from the Canterbury region. This led to the belief for a time that Canterbury might become the natural home for Pinot noir in New Zealand. While the early excitement passed, the Canterbury region has witnessed the development of Pinot noir as the dominant red variety. The sub-region Waipara has some interesting wines. Producers include Waipara Hills, Pegasus Bay, Waipara Springs, Muddy Water, Greystone, Omihi Hills and Black Estate.

The next region to excel with Pinot noir was Martinborough on the southern end of the North Island. Several vineyards including Palliser Estate, Martinborough Vineyards, Murdoch James Estate and Ata Rangi consistently produced interesting and increasingly complex wine from Pinot Noir at the end of the 1980s and into the 1990s.

At around this time the first plantings of Pinot noir in Central Otago occurred in the Kawarau Gorge. Central Otago had a long (for New Zealand) history as a producer of quality stone fruit and particularly cherries. Significantly further south than all other wine regions in New Zealand, it had been overlooked despite a long history of grape growing. However, it benefited from being surrounded by mountain ranges which increased its temperature variations both between seasons and between night and day making the climate unusual in the typically maritime conditions in New Zealand. In recent years Pinot noir from Central Otago has won numerous international awards and accolations making it one of New Zealand's most sought-after varieties.

The first vines were planted using holes blasted out of the north facing schist slopes of the region, creating difficult, highly marginal conditions. The first results coming in the mid to late 1990s excited the interest of British wine commentators, including Jancis Robinson and Oz Clarke. Not only did the wines have the distinctive acidity and abundant fruit of New Zealand wines, but they demonstrated a great deal of complexity, with aromas and flavours not common in New Zealand wine and normally associated with burgundian wine. Producers include Akarua, Felton Rd, Chard Farm and Mt Difficulty.

The latest sub-region appears to be Waitaki, on the border between Otago and Canterbury.

In a blind tasting of New Zealand Pinot noir featured in Cuisine magazine (issue 119), Michael Cooper reported that of the top ten wines, five came from Central Otago, four from Marlborough and one from Waipara. This compares with all top ten wines coming from Marlborough in an equivalent blind tasting from last year. Cooper suggests that this has to do with more Central Otago production becoming available in commercial quantities, than the relative qualities of the regions' Pinot noir.

As is the case for other New Zealand wine, New Zealand Pinot noir is fruit-driven, forward and early maturing in the bottle. It tends to be quite full bodied (for the variety), very approachable and oak maturation tends to be restrained. High quality examples of New Zealand Pinot noir are distinguished by savory, earthy flavours with a greater complexity. In an article in Decanter (September 2014), Bob Campbell suggests that regional styles are starting to emerge within New Zealand Pinot Noir. Marlborough, with by far the largest plantings of Pinot, produces wines that are quite aromatic, red fruit in particular red cherry, with a firm tannic structure that provides cellaring potential.

Central Otago with the second highest area planted, has strong, sweet plum and cherry flavours and thyme notes. In wines from cooler sub-regions there are edgier qualities with fresh herb, spice and pronounced mineral flavours. Wairarapa produces wines that are lighter, softer and more supple. Waipara in Canterbury has two styles. Wines produced on the flat valley floor are lighter and supple and have a bias toward red fruits. Pinot produced on the surrounding hills appear more concentrated, with dark fruit flavours and occasionally with a chalk/mineral influence. Nelson is similarly divided into two sub-regions with the Waimea plains producing accessible wines with vibrant acidity and those from the Moutere Valley producing wine that is richer, more concentrated and structured.

White

In white wines Chardonnay and Sauvignon blanc predominate in plantings and production. Typically Chardonnay planting predominate more the further north one goes, however it is planted and produced in Central Otago. There is no discernible difference in styles for Chardonnay between the New Zealand wine regions so far. Individual wine makers and the particular qualities of a vintage are more likely to determine factors such as malolactic fermentation or the use of oak for aging.

New Zealand Sauvignon blanc has been described by some as "alive with flavors of cut grass and fresh fruits", and others as "cat's pee on a gooseberry bush" (but not necessarily as a criticism).

Other white varietals commonly include (in no particular order) Riesling, Gewürztraminer, and Pinot gris, and less commonly Chenin blanc, Pinot blanc, Müller-Thurgau and Viognier.

Riesling is produced predominantly in Martinborough and south. The same may be said with less forcefulness about Gewürztraminer (which is also planted extensively in Gisborne). Pinot gris is being planted increasingly, especially in Martinborough and the South Island. Chenin blanc was once more important, but the viticultural peculiarities of the variety, particularly its unpredictable cropping in New Zealand, have led to its disfavor. Milton Estate in Gisborne produces an example of this variety.

The market success of Sauvignon blanc, Chardonnay and lately Pinot noir mean that these varietals will dominate future planting.

Sparkling wine

Excellent quality Methode Traditionelle sparkling wine is produced in New Zealand. Typically, it was Marlborough that was the commercial birthplace of New Zealand Methode Traditionelle sparkling wine. Marlborough still produces a number of high quality sparkling wines, and has attracted both investment from Champagne producers (Deutz) and also champanois wine-makers (Daniel Le Brun). Other sparkling wines from Marlborough include Pelorus (from Cloudy Bay), and the now venerable Lion Nathan brand, Lindauer.

Wine regions of New Zealand

Northland

The most northerly wine region in New Zealand, and thus closest to the equator.

Auckland

This region lies around New Zealand's largest city. Producing mainly red wines from grapes grown on heavy clay soil. It is the warmest New Zealand's vine-growing areas.

Waiheke Island

Waiheke Island is east of Auckland in the Hauraki Gulf. For New Zealand it has a dry and warm meso-climate. Its red wine is significantly riper and more full bodied. It is home to Stonyridge Estate that produces a bordeaux blend called the Larose, which is one of the most expensive and prestigious New Zealand red wines. Destiny Bay Vineyards, Obsidian Vineyard, Peacock Sky, Goldwater Estate, Cable Bay, Mudbrick and Te Motu also produce on Waiheke.

Waikato/Bay of Plenty

This area is also known for growing kiwifruit and apples.

Gisborne

A small wine region to the north of Hawkes Bay. Noted for its Chardonnay and Gewürztraminer. It is also the world's most easterly vine producing region.

Hawke's Bay

Hawke's Bay, along with Marlborough, is the centre of gravity for the New Zealand wine industry; it is New Zealand's oldest wine producing area and is the country's second largest wine production region. The premiere area for Bordeaux blend reds in New Zealand and the region is rapidly developing a reputation for quality Syrah. Chardonnay and Sauvignon blanc are produced and lately Viognier. Specialist high quality small producers include Bilancia and Bridge Pa. Other well-known producers include Brookfields Estate, Clearview Estate, Esk Valley, Villa Maria, Vidal, Trinity Hill, Craggy Range, Newton Forrest Estate, Te Mata Estate, Moana Park Estate, Mission Estate, Sileni, Sacred Hill, CJ Pask, and Babich.

Wellington/Wairarapa

The Wellington/Wairarapa wine-growing region is one of New Zealand's smallest, with several sub-regions, which include Gladstone, Martinborough, Masterton, and Opaki. Martinborough was the original area planted, on the basis of careful scientific study, in the 1970s, which identified its soils and climate as perfectly suited to the cultivation of Pinot noir. As a consequence, many of the vineyards established there are older than their counterparts in the rest of the Wairarapa. Subtle differences are seen in the wines from the South Wairarapa (which includes Martinborough), which has more maritime influences, to those grown further north.

Martinborough

Martinborough is a small wine village located at the foot of New Zealand’s North Island, in the South Wairarapa, just 1.5 hours drive from Wellington, the capital city. The combination of topography, geology, climate and human effort has led to the region becoming one of New Zealand's premier wine regions in spite of its small size. Less than 2% of the country's wine production is grown in Martinborough, yet in shows and competitions, it rates much more highly. The local Winegrowers organization states: "Officially New Zealand's sixth largest region, Wellington/Wairarapa is small in production terms but makes a large contribution to the country's quality winemaking reputation.".[4]

The vineyards are shielded from the elements by steep mountains, while the growing season from flowering to harvest is amongst the longest in New Zealand. Naturally breezy conditions control vine vigor, creating lower yields of grapes with greater intensity. A genuine cool climate, with a long, dry autumn in NZ, provides an ideal ripening conditions for Pinot noir and other varietals, such as Riesling, Syrah and Pinot gris. A small number of wineries are producing Cabernet Franc of a high standard. Most of the wineries are located on the area's alluvial river terraces near the township (the Te Muna, Huangarau and Dry River Regions).

Martinborough wineries are relatively small and typically family-owned, with the focus on producing quality rather than quantity. Relatively small yields enable Martinborough winemakers to devote themselves to handcrafting superior wines. Among the many long-established wineries, several, including Te Kairanga, Ata Rangi, Palliser Estate, Murdoch James Estate and Dry River, have become internationally recognized as premium producers of Pinot noir.

Key production figures:

- The total Wellington/Wairarapa producing area is 758ha.

- The Wairarapa currently has 54 wineries, more than twice the 24 in the region in 1995.

- Predominant varieties for the 2006 vintage were: Pinot noir (38%); Sauvignon blanc (35%); Chardonnay (11%); Riesling (0.08%); Pinot gris (0.03%).& the Cabernets - including Cab sauvignon & franc (0.012%); and the remaining 16% includes Merlot, Syrah, Malbec, and Gewürztraminer.

- In 2007, the producing area in Wellington/Wairarapa represented just two percent of the total New Zealand wine producing area.

Nelson

Many people believe Nelson has the best climate in New Zealand, as it regularly tops the national statistics for sunshine hours, with an annual average total of over 2400 hours.the long autumns here permit the production of fine late-harvest wines.[5]

Marlborough including Wairau Valley

In many respects, the Wairau Valley and the districts surrounding Blenheim are the home of the modern New Zealand wine industry. It is the largest wine district in terms of production and area under vines. It has a number of sub-regions including the Waihopai valley, Renwick and the Spring Creek area.

Canterbury/Waipara

Omihi Hills and Waipara

In many respects the most well-known Canterbury area for Pinot noir. Good examples of Pinot noir include Mountford Estate, Black Estate, Waipara Hills, Omihi Hills, Greystone, Waipara Springs, Pegasus Bay and Crater Rim. White wines of the region include Chardonnay, Sauvignon blanc and Riesling.

Waikari and Cheviot

Inland from Waipara, the limestone soils of the Waikari area are producing some of the most sought-after wines in New Zealand where producers such as Bell Hill and Pyramid Valley carve out a niche with biodynamic, close-planted vineyards. However production in both these areas remains very limited

South of Waipara, Amberley and North of Christchurch

Amberley is a few kilometres south of the Waipara River. It produced a break-through Riesling for Corbans in the early eighties, but recently it has diminished in production. St Helena Estate was a long established vineyard south of the Waimakariri River and north of Belfast. But it has closed.

West Melton, Banks Peninsula and Rolleston

Wine makers in this general area include French Peak (formerly French Farm), Tresillian, Sandihurst, Melton Estate, and Lone Goat (Formally Giesen Estate which has moved to Marlborough). Wines are predominantly white including Chardonnay, Riesling, Gewürztraminer, Pinot blanc, and Pinot gris, and Sauvignon blanc. While not as well known as Waipara for producing Pinot Noir, many mid Canterbury winemakers are nonetheless well respected for producing "earthy" Pinot noir with a "forest floor" characters.

Waitaki River Basin

New Zealand's newest wine growing region, located on the border of Otago and Canterbury. Wine producers include Pasquale, Ostler, Waitaki Braids and Forrest. Pinot noir is produced here, as well as white aromatic varieties including Riesling, Pinot gris, Gewürztraminer and Chardonnay.

Central Otago

The most southerly wine producing region in the world. The vineyards are also the highest in New Zealand at 200 to 400 metres above sea level on the steep slopes of lakesides and the edges of deep river gorges, often also in glacial soils. Central Otago is a sheltered inland area with a continental microclimate characterised by hot, dry summers, short, cool autumns and crisp, cold winters. Divided into several subregions around Bannockburn, Bendigo, Gibbston/Queenstown, Wanaka, the Kawarau Gorge, the Alexandra Basin, and the Cromwell Basin

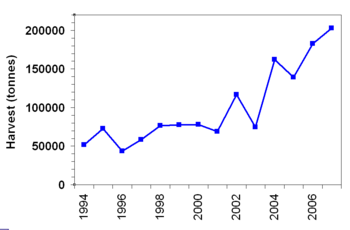

Trends in production and export

The initial focus for the industry's export efforts was the United Kingdom. The late 1970s and early 1980s were not only pioneering times for production but also marketing and as with many New Zealand products, wine was only really taken seriously at home when it was noticed and praised overseas and in particular by British wine commentators and critics. For much of the history of New Zealand wine exportation the United Kingdom market, with its lack of indigenous production, great thirst and sophisticated wine pallate has been either the principal or only market. In the last decade the British market's overwhelming importance has eroded; while still the single largest export market, it now (2006) makes up only one third of total exports by value, only slightly larger than the American and Australian markets.[6] Japan is a particularly strong importer of high-end New Zealand wines: in 2006, it spent NZ$14.44 per liter of wine imported, compared to New Zealand's average price of NZ$8.87/L.[7]

New Zealand's wine industry has become highly successful in the international market. To meet the increasing demand for its wines, the country's vineyard plantings have more than tripled in the ten years ending in 2005. Sales continue to increase. For example, "From 2004 to 2005, exports to the United States skyrocketed 81 percent to 1.45 million cases, more than two-thirds of which was Sauvignon blanc, still the country's undisputed flagship wine."

The trend at midpoint in 2008 is an increased recognition for the small artisan wineries. These small wineries represent over 80% of New Zealand's total producers and are located throughout all wine regions.

In 2008, The Economist reported that wine overtook wool exports in value for the first time, and became the country's 12th most valuable export, worth NZ$760m ($610m), up from NZ$94m in 1997. New Zealand Winegrowers (NZWG), a national trade body, stated that the industry sold 1 billion glasses of wine in nearly 100 countries. New Zealand accounted for over 10% of wines sold in Britain for more than £5 ($10).[8]

In August, 2014, the NZ Winegrowers Annual Report stated export sales had risen 10% on the previous year, with sales hitting a new record of NZ $1.33 billion. The industry's goal is topping NZ $2 billion and becoming a top 5 export industry. The report also showcased the industry's growing emphasis on sustainability. Sustainability and organic programs certify around 95% of NZ's vineyard producing area. Social sustainability is as large a focus as environmental, the report said.[9]

Praise and criticism

Cloudy Bay Vineyards set a new standard for New World Sauvignon blanc and was arguably responsible for the huge increase in interest in such wines, particularly in the United Kingdom. Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy, a French luxury brand conglomerate, now owns a controlling interest in Cloudy Bay.

Following on from the early success of Sauvignon blanc, New Zealand has been building a strong reputation with other styles; Chardonnay, Cabernet/Merlot blends, Pinot noir, Pinot gris and Syrah to name a few.

UK wine writer Paul Howard observes, when commenting on New Zealand Pinot noir that, while "comparisons with Burgundy are inevitable, New Zealand Pinot noir is rapidly developing its own distinctive style, often with deeper color, purer fruit and higher alcohol. While regional differences are apparent, the best wines do have Burgundy’s elusive complexity, texture and “pinosity” and are capable of ageing". He goes on to say "It is a testament to the skill and craft of New Zealand producers that poor examples are infrequently encountered".[10][11]

Statistics

| Year | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Productive wine area (hectares) | 6,110 | 6,610 | 7,410 | 7,580 | 9,000 | 10,197 | 11,648 | 13,787 | 15,800 | 18,112 | 21,002 | 22,616 | 25,355 | 29,310 | 31,964 | 33,428 | 33,400 | 35,335 | 35,733 |

| Total Production (millions of litres) | 56.4 | 57.3 | 45.8 | 60.6 | 60.2 | 60.2 | 53.3 | 89.0 | 55.0 | 119.2 | 102.2 | 133.2 | 147.6 | 205.2 | 205.2 | 190.0 | 235.0 | 194.0 | 248.4 |

| Year | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sauvignon blanc | 4,516 | 5,897 | 7,043 | 8,860 | 10,491 | 13,988 | 16,205 | 16,910 | 16,758 | 20,270 | 20,429 |

| Chardonnay | 3,515 | 3,617 | 3,731 | 3,779 | 3,918 | 3,881 | 3,911 | 3,865 | 3,823 | 3,229 | 3,253 |

| Pinot noir | 2,624 | 3,239 | 3,623 | 4,063 | 4,441 | 4,650 | 4,777 | 4,773 | 4,803 | 5,388 | 5,425 |

| Merlot | 1,249 | 1,487 | 1,492 | 1,420 | 1,447 | 1,363 | 1,369 | 1,371 | 1,386 | 1,234 | 1,262 |

| Riesling | 653 | 666 | 806 | 853 | 868 | 917 | 979 | 986 | 993 | 770 | 796 |

| Cabernet Sauvignon | 741 | 687 | 678 | 531 | 524 | 516 | 517 | 519 | 519 | 305 | 331 |

By region

| Region | Vineyard area (ha) | Tonnes crushed |

|---|---|---|

| Auckland & Northland | 416 | 1,602 |

| Waikato & Bay of Plenty | 23 | 63 |

| Gisborne | 1,602 | 16,192 |

| Hawke's Bay | 4,816 | 44,502 |

| Wairarapa | 997 | 5,743 |

| Marlborough | 22,903 | 329,572 |

| Nelson & Tasman | 1,115 | 10,494 |

| Canterbury (incl. Waipara) | 1,462 | 10,962 |

| Central Otago | 1,979 | 10,540 |

See also

References

- Oldman, Mark. Oldman's Guide to Outsmarting Wine. NY: Penguin, 2004.

- Rachman, Gideon. "The globe in a glass". The Economist, 16 December 1999.

- Sogg, Daniel. "Standout Sauvignons", Wine Spectator, 10 November 2005, p. 108-111.

- Taber, George M. Judgment of Paris: California vs France and the Historic 1976 Paris Tasting that Revolutionized Wine. NY: Scribner, 2005.

- Footnotes

- ↑ winepros.com.au. Oxford Companion to Wine. "New Zealand".

- ↑ "Hawkes Bay Wineries". Jasons Travel Media.

- ↑ http://www.nzherald.co.nz/viva-magazine/news/article.cfm?c_id=533&objectid=11349492

- ↑ nzwine.com New Zealand Wine Regions

- ↑ "Mean Monthly There are two sub-regions in Nelson: Waimea and Moutere Valley. Sunshine". NIWA. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ↑ "(NZ) Wine Exports". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ↑ "New Zealand Winegrowers Statistical Annual 2006" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ↑ http://www.economist.com/node/10926423

- ↑ http://www.nzwine.com/assets/sm/upload/b5/2j/rr/2n/NZW%20AR%202014_web.pdf

- ↑ "New Zealand - what's the latest?", JancisRobinson.com

- ↑ "New Zealand – a personal view"

- 1 2 New Zealand Winegrowers Statistical Annual 2007, 2008 and 2013

- ↑ "New Zealand Winegrowers Annual Report 2014" (PDF). New Zealand Winegrowers. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Viticulture in New Zealand. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||