Pennsylvania Station (New York City)

Pennsylvania Station, also known as New York Penn Station or Penn Station, is the main intercity railroad station in New York City. Serving more than 600,000 commuter rail and Amtrak passengers a day, it is the busiest passenger transportation facility in North America. Penn Station is in the midtown area of Manhattan, close to Herald Square, the Empire State Building, Koreatown, and the Macy's department store. Entirely underground, it sits beneath Madison Square Garden, between Seventh Avenue and Eighth Avenue and between 31st and 34th Streets.

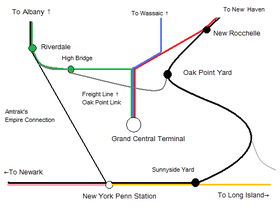

Penn Station has 21 tracks fed by seven tunnels (the North River Tunnels (beneath the Hudson River), the East River Tunnels, and the Empire Connection tunnel). It is at the center of the Northeast Corridor, a passenger rail line that connects New York City with Boston, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and intermediate points. Intercity trains are operated by Amtrak, which owns the station, while commuter rail services are operated by the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) and New Jersey Transit. Connections are available within the complex to the New York City Subway, and buses.

The original Pennsylvania Station was built from 1901-1910 by the Pennsylvania Railroad, and featured an ornate marble and granite station house and train shed inspired by the Gare d'Orsay in Paris (the world's first electrified rail terminal). After a decline in passenger usage during the 1950s, the original station was demolished and reconstructed from 1963 to 1969, resulting in the current station. Future plans for Penn Station include the possibility of shifting some trains to the adjacent Farley Post Office, a building designed by the same architects as the original 1910 station. Since 2011, there has also a preliminary discussion of increasing passenger capacity as part of the Gateway Project, a proposal to build two new tunnels under the Hudson River and streamline track connections in New Jersey.

History

Pennsylvania Station is named for the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), its builder and original tenant, and shares its name with several stations in other cities. The current facility is the substantially remodeled underground remnant of a much grander station building designed by McKim, Mead, and White and completed in 1910. The original Pennsylvania Station was considered a masterpiece of the Beaux-Arts style, but was demolished in 1963. The station was moved fully underground, beneath the newly constructed Pennsylvania Plaza complex and Madison Square Garden arena completed in 1968.

Planning and construction (1901–1910)

Until the early 20th century, the PRR's rail network terminated on the western side of the Hudson River (once known locally as the North River) at Exchange Place in Jersey City, New Jersey. Manhattan-bound passengers boarded ferries to cross the Hudson River for the final stretch of their journey. The rival New York Central Railroad's line ran down Manhattan from the north under Park Avenue and terminated at Grand Central Terminal at 42nd St.

The Pennsylvania Railroad considered building a rail bridge across the Hudson, but the state required such a bridge to be a joint project with other New Jersey railroads, who were not interested.[4][5] The alternative was to tunnel under the river, but steam locomotives could not use such a tunnel due to the accumulation of pollution in a closed space; in any case the New York State Legislature had prohibited steam locomotives in Manhattan after July 1, 1908.[6] The development of the electric locomotive at the turn of the 20th century made a tunnel feasible. On December 12, 1901, PRR president Alexander Cassatt announced the railroad's plan to enter New York City by tunneling under the Hudson and building a grand station on the West Side of Manhattan south of 34th Street. The station would sit in Manhattan's Tenderloin district, a historical red-light district known for its corruption and prostitution.[7]

Beginning in June 1903, the two single-track North River Tunnels were bored from the west under the Hudson River. A second set of four single-track tunnels were bored from the east under the East River, linking the new station to Queens and the Long Island Rail Road, which came under PRR control (see East River Tunnels), and Sunnyside Yard in Queens, where trains would be maintained and assembled. Electrification was initially 600 volts DC–third rail, and later changed to 11,000 volts AC–overhead catenary when electrification of PRR's mainline was extended to Washington, D.C., in the early 1930s.[4]

The tunnel technology was so innovative that in 1907 the PRR shipped an actual 23-foot (7.0 m) diameter section of the new East River Tunnels to the Jamestown Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia, to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the nearby founding of the colony at Jamestown. The same tube, with an inscription indicating that it had been displayed at the Exposition, was later installed under water and remains in use today. Construction was completed on the Hudson River tunnels on October 9, 1906, and on the East River tunnels on March 18, 1908. Meanwhile, ground was broken for Pennsylvania Station on May 1, 1904. By the time of its completion and the inauguration of regular through train service on November 27, 1910, the total project cost to the Pennsylvania Railroad for the station and associated tunnels was $114 million (about $2.7 billion in 2011 dollars), according to an Interstate Commerce Commission report.[8]:156–7

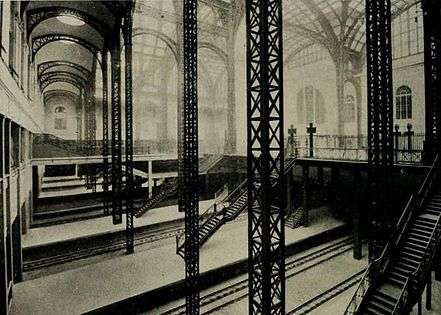

Original structure (1910–1963)

During half a century of operation by the Pennsylvania Railroad (1910–1963), scores of intercity passenger trains arrived and departed daily to Chicago and St. Louis on “Pennsy” rails and beyond on connecting railroads to Miami and the west. Along with Long Island Rail Road trains, Penn Station saw trains of the New Haven and the Lehigh Valley Railroads. A side effect of the tunneling project was to open the city up to the suburbs, and within 10 years of opening, two-thirds of the daily passengers coming through Penn Station were commuters.[7] The station put the Pennsylvania Railroad at comparative advantage to its competitors offering direct service from Manhattan to the west and south. By contrast the Baltimore & Ohio, Central of New Jersey, Erie, West Shore Railroad, New York, Susquehanna and Western and the Lackawanna railroads began their routes at terminals in Weehawken, Hoboken, Pavonia and Communipaw which required passengers from New York City to use ferries or the interstate Hudson Tubes to traverse the Hudson River before boarding their trains.

During World War I and the early 1920s, rival Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) passenger trains to Washington, Chicago, and St. Louis also used Penn Station, initially by order of the United States Railroad Administration, until the Pennsylvania Railroad terminated the B&O's access in 1926.[9] By 1945, at its peak, more than 100 million passengers a year traveled through Penn Station.[7] The station saw its heaviest use during World War II. By the late 1950s, intercity, rail passenger volumes had declined dramatically with the coming of the Jet Age and the Interstate Highway System. After a renovation covered some of the grand columns with plastic and blocked off the spacious central hallway with a new ticket office, author Lewis Mumford wrote critically in The New Yorker in 1958 that “nothing further that could be done to the station could damage it.”

The Pennsylvania Railroad optioned the air rights of Penn Station in the 1950s. The option called for the demolition of the head house and train shed, to be replaced by an office complex and a new sports complex. The tracks of the station, perhaps 50 feet below street level, would remain untouched.[10] Plans for the new Penn Plaza and Madison Square Garden were announced in 1962. In exchange for the air rights to Penn Station, the Pennsylvania Railroad would get a brand-new, air-conditioned, smaller station completely below street level at no cost, and a 25 percent stake in the new Madison Square Garden Complex.

Demolition of the original structure

The cost of maintaining the old structure had become prohibitive, so it was considered easier to demolish the old Pennsylvania Station by 1963 and replace it with Penn Plaza and Madison Square Garden. As a New York Times editorial critical of the demolition noted at the time, a "city gets what it wants, is willing to pay for, and ultimately deserves."[11] Modern architects rushed to save the ornate building, although it was contrary to their own styles. They called the station a treasure and chanted "Don't Amputate – Renovate" at rallies.[12] Demolition of the above-ground station house began in October 1963. As most of the rail infrastructure was below street level, including the waiting room, concourses, and boarding platforms, rail service was maintained throughout demolition with only minor disruptions. Madison Square Garden, along with two office towers were built above the extensively renovated concourses and waiting area (the tracks and boarding platforms were not modified at this time).[13] A 1968 advertisement depicted architect Charles Luckman's model of the final plan for the Madison Square Garden Center complex.[14]

The demolition of the head house was very controversial and caused outrage internationally.[15] The New York Times wrote: "Until the first blow fell, no one was convinced that Penn Station really would be demolished, or that New York would permit this monumental act of vandalism against one of the largest and finest landmarks of its age of Roman elegance."[11] "One entered the city like a God," the architectural historian Vincent Scully famously wrote of the original station. "One scuttles in now like a rat."[16]

The controversy over the demolition of such a well-known landmark, and its deplored replacement,[17] is often cited as a catalyst for the architectural preservation movement in the United States. New laws were passed to restrict such demolition. Within the decade, Grand Central Terminal was protected under the city's new landmarks preservation act, a protection upheld by the courts in 1978 after a challenge by Grand Central's owner, Penn Central.[18]

Current structure (1968–present)

The current Penn Station is completely underground, and sits below Madison Square Garden, 33rd Street, and Two Penn Plaza. The station has three underground levels: concourses on the upper two levels and train platforms on the lowest. The two levels of concourses, while original to the 1910 station, were extensively renovated during the construction of Madison Square Garden, and expanded in subsequent decades. The tracks and platforms are also largely original, except for some work connecting the station to the West Side Rail Yard and the Amtrak Empire Corridor serving Albany and Buffalo, New York.[19][20]

In the 1990s, the current Pennsylvania Station was renovated by Amtrak, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, and New Jersey Transit, to improve the appearance of the waiting and concession areas, sharpen the station information systems (audio and visual) and remove much of the grime. Recalling the erstwhile grandeur of the bygone Penn Station, an old four-sided clock from the original depot was installed at the 34th Street Long Island Rail Road entrance. The walkway from that entrance's escalator also has a mural depicting elements of the old Penn Station's architecture.

There is an abandoned underground passageway from Penn Station to the nearby 34th Street – Herald Square subway station. It was closed in the 1990s.

After the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, passenger flow through the Penn Station complex was curtailed. The taxiway under Madison Square Garden, which ran from 31st Street north to 33rd Street half way between 7th and 8th Avenues, was closed off with concrete Jersey barriers. A covered walkway from the taxiway was constructed to guide arriving passengers to a new taxi-stand on 31st Street.

Despite the improvements, Penn Station continues to be criticized as a low-ceilinged "catacomb" lacking charm, especially when compared to New York's much larger and ornate Grand Central Terminal.[15] The New York Times, in a November 2007 editorial supporting development of an enlarged railroad terminal, said that "Amtrak's beleaguered customers...now scurry through underground rooms bereft of light or character."[21] Times transit reporter Michael M. Grynbaum later called Penn Station "the ugly stepchild of the city’s two great rail terminals."[22]

Services

The station serves 1,200 trains a day.[23] There are more than 600,000 commuter rail and Amtrak passengers who use the station on an average weekday,[24][25] or up to one thousand every ninety seconds.[26] It is the busiest passenger transportation facility in the United States[27] and in North America.[28][29]

Intercity railAmtrakMain article: Amtrak

Amtrak owns the station and uses it for the following services:

Despite its status as the busiest train station for Amtrak, Pennsylvania Station does not have adequate clearance for its Superliner railcars. Amtrak normally uses tracks 5–16 alongside New Jersey Transit which also uses tracks 1-4 as well as the LIRR for 13–16. Commuter railLong Island Rail RoadMain article: Long Island Rail Road

All branches connect at Jamaica station except the Port Washington Branch. Normally, the LIRR uses tracks 17–21 exclusively and shares 13–16 with Amtrak and NJT. New Jersey TransitMain article: New Jersey Transit Rail Operations

Passengers can transfer at Secaucus Junction to Main Line, Bergen County Line, Port Jervis Line, and Pascack Valley Line trains, as well as Meadowlands Rail Line event service. The first Dual-Powered(Diesel & Electric) train arrived on March 8, 2013 from the Montclair-Boonton Line because of electrical work happening on the line. NJT normally has the exclusive use of tracks 1–4, and shares tracks 5–16 with Amtrak and tracks 13–16 with the LIRR as well. |

Rapid transitNew York City SubwayFurther information: New York City Subway

PATHFurther information: Port Authority Trans-Hudson

Bus and coachNew York City BusFurther information: MTA Regional Bus Operations

Intercity coachBoltBusBoltBus is a discount bus company owned and operated under a 50/50 partnership between Greyhound and Peter Pan bus lines. They operate intercity bus service from two stops at Penn Station: Penn Station Bus Stop #1 (West 33rd Street and 7th Avenue)

Penn Station Bus Stop #2 (West 34th Street and 8th Avenue)

Vamoose BusVamoose Bus is a private company that runs buses from a stop near Penn Station (West 30th Street and 7th Avenue) to Bethesda Station, Bethesda, Maryland; Rosslyn Station, Arlington, Virginia; Lorton VRE Station, Lorton, Virginia.[30] Tripper BusTripper Bus is a private company that runs buses from a stop near Penn Station (31st Street between 8th & 9th Avenue) to Bethesda Station, Bethesda, Maryland; and Rosslyn Station, Arlington, Virginia. Go BusesGo Buses is a private company that runs buses from a stop near Penn Station (31st Street between 8th & 9th Avenue) to Riverside Station, Newton, Massachusetts, and Alewife Station, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Airline ticketingPenn Station includes a United Airlines ticketing office, located at the ticket lobby.[31] This was previously a Continental Airlines ticketing office.[32] |

Proposed Metro-North service

The Metropolitan Transportation Authority has proposed to bring Metro-North Railroad commuter trains to Penn Station as part of its Penn Station Access project. The first phase of the project would bring New Haven Line trains to Penn Station via Amtrak's Hell Gate Line/Northeast Corridor and the East River Tunnels. The second phase would bring Hudson Line service to the station via the Empire Corridor and Empire Connection.[33]

Station layout

Unlike most train stations, Penn Station does not have a unified design or floor plan but rather is divided into separate Amtrak, Long Island Rail Road and New Jersey Transit concourses with each concourse maintained and styled differently by its respective operator. Amtrak and NJ Transit concourses are located on the first level below the street-level while the Long Island Rail Road concourse is two levels below street-level. The NJ Transit concourse near Seventh Avenue is the newest and opened in 2002 out of existing retail and Amtrak office space.[34][35] A new entrance to this concourse from West 31st Street opened in September 2009.[36] Previously, NJ Transit shared space with the Amtrak concourse. The main LIRR concourse runs below West 33rd Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. Significant renovations were made to this concourse over a three-year period ending in 1994, including the addition of a new entry pavilion on 34th Street.[37] The LIRR's West End Concourse, west of Eighth Avenue, opened in 1986.[38]

In normal operations, tracks 1–4 are used by NJ Transit, and tracks 5–12 are used by Amtrak and NJ Transit trains. Normally the LIRR has the exclusive use of tracks 17–21 on the north side of the station and shares tracks 13–16 with Amtrak and NJ Transit.

| Station layout | ||

|---|---|---|

| Above ground | Madison Square Garden/Two Penn Plaza[39] | |

| G | Street Level | Exit/Entrance |

| UC | Amtrak Concourse | Amtrak tickets, transfer to 34th Street – Penn Station (IND Eighth Avenue Line) station; exit to 33rd Street, connection to Exit and Connecting concourses[39] |

| NJT Concourse | NJT tickets, exit to 31st Street, connect to LIRR and Hilton concourses[39] | |

| LC | West End Concourse | Amtrak/LIRR tickets, transfer to 34th Street – Penn Station (IND Eighth Avenue Line) station; exit to 33rd Street, connection to Exit and Connecting concourses[39] |

| Exit Concourse | Exit to 31st Street, connection to Hilton, West End, and Connecting concourses[39] | |

| Hilton Corridor | Exit to Seventh Avenue, connection to Exit, LIRR, Central, and NJT concourses[39] | |

| Central Concourse | Tickets, connection to Connecting and Hilton concourses[39] | |

| Connecting Concourse | Transfer to 34th Street – Penn Station (IRT Broadway – Seventh Avenue Line) station, connection to West End, LIRR, Central, and Exit concourses, to One Penn Plaza and 34th Street at north end[39] | |

| LIRR Concourse | LIRR tickets, connection to NJT and Hilton concourses[39] | |

| P Platform level |

Track 21 | → LIRR → |

| Island platform (Platform K) | ||

| Track 20 | → LIRR → | |

| Track 19 | → LIRR → | |

| Island platform (Platform J) | ||

| Track 18 | → LIRR → | |

| Island platform (Platform I); Track 17 only | ||

| Track 17 | → LIRR → | |

| Track 16 | ← Amtrak/New Jersey Transit/LIRR → | |

| Island platform (Platform H) | ||

| Track 15 | ← Amtrak/New Jersey Transit/LIRR → | |

| Track 14 | ← Amtrak/New Jersey Transit/LIRR → | |

| Island platform (Platform G) | ||

| Track 13 | ← Amtrak/New Jersey Transit/LIRR → | |

| Track 12 | ← Amtrak/New Jersey Transit → | |

| Island platform (Platform F) | ||

| Track 11 | ← Amtrak/New Jersey Transit → | |

| Track 10 | ← Amtrak/New Jersey Transit → | |

| Island platform (Platform E) | ||

| Track 9 | ← Amtrak/New Jersey Transit → | |

| Track 8 | ← Amtrak/New Jersey Transit → | |

| Island platform (Platform D) | ||

| Track 7 | ← Amtrak/New Jersey Transit → | |

| Track 6 | ← Amtrak/New Jersey Transit → | |

| Island platform (Platform C) | ||

| Track 5 | ← Amtrak/New Jersey Transit → | |

| Track 4 | ← New Jersey Transit | |

| Island platform (Platform B) | ||

| Track 3 | ← New Jersey Transit | |

| Track 2 | ← New Jersey Transit | |

| Island platform (Platform A) | ||

| Track 1 | ← New Jersey Transit | |

Tracks and surrounding infrastructure

Tracks 1-4 end at bumper blocks at the eastern end of the platform.

Due to the narrowness of platform I, trains on Track 18 will usually not open their doors on that platform. Trains on track 18 open their doors on Platform J, which is the station's widest platform.

Normally, the LIRR uses tracks 17–21 exclusively and shares 13–16 with Amtrak and NJT. NJT normally has the exclusive use of tracks 1–4, and shares tracks 5–16 with Amtrak and tracks 13–16 with the LIRR. Amtrak normally uses tracks 5–16 alongside New Jersey Transit, as well as 13–16 shared with the LIRR. Empire Connection trains along the Empire Corridor can only use tracks 5–9 due to the track layout.

Tracks 1–4 are powered solely by 12 kV overhead wire. Tracks 5–21 have both overhead wire and 750 V DC third rail.

The North River Tunnels cannot access tracks 20 and 21, but can access tracks 1–19. The Empire Connection can only access tracks 1–9. The LIRR's West Side Yard can only access tracks 10–21. The East River Tunnels' lines 1 and 2 can only access tracks 5–17 and are used by most Amtrak and NJ Transit trains, while the East River Tunnels' lines 3 and 4 can only access tracks 14–21 and are mostly used by LIRR.[40]

Due to the lack of proper ventilation in the tunnels and station, only electric locomotives and dual-mode locomotives are scheduled to enter Penn Station. Diesel-only NJT trains terminate at Hoboken Terminal or Newark Penn Station, and diesel-only LIRR trains terminate at or prior to Long Island City.

Platform access

Although most Amtrak passengers board via the escalators in the main Amtrak boarding area, multiple entrances exist for each platform.[41]

ClubAcela Lounge

ClubAcela is a private lounge located on the Amtrak concourse (8th Avenue side of the station). Prior to December 2000 it was known as the Metropolitan Lounge. Guests are provided with comfortable seating, complimentary non-alcoholic beverages, newspapers, television sets and a conference room. Access to ClubAcela is restricted to the following passenger types:[42]

- Amtrak Guest Rewards members with a valid Select Plus or Select Executive member card.

- Amtrak passengers with a same-day ticket (departing) or ticket receipt (arriving) in First class or sleeping car accommodations.

- Complimentary ClubAcela Single-Day Pass holders.

- United Airlines United Club Members with a valid card or passengers with a same-day travel ticket on United GlobalFirst or United BusinessFirst.

- Private rail car owners/lessees. The PNR number must be given to a Club representative upon entry.

Enclosed waiting area

Amtrak also offers an enclosed waiting area for ticketed passengers with seats, outlets and WiFi.[43]

Planning and redevelopment

Gateway Project

The Gateway Project is a proposed high-speed rail corridor to alleviate the bottleneck along the Northeast Corridor at the North River Tunnels, which runs under the Hudson River. If constructed, the project would add 25 cross-Hudson train slots during rush hours, convert parts of the James Farley Post Office into a rail station, and add a terminal annex to Penn Station. Some previously planned improvements already underway have also been incorporated into the Gateway plan.

The Gateway Project was unveiled in 2011, one year after the cancellation of the somewhat similar Access to the Region's Core (ARC) project, and was originally projected to cost $14.5 billion and take 14 years to build. In 2015, Amtrak reported that environmental and design work was underway, estimated the project's total cost at $20 billion, and said construction would start in 2019 or 2020 and last four to five years.[44]

In 2015, Amtrak said that damage done to the existing trans-Hudson tunnels by 2012's Hurricane Sandy had made their replacement urgent. Construction of a "tunnel box" that would preserve the right-of-way on Manhattan's West Side began in September 2013, using $185 million in Hurricane Sandy recovery and resilience funding.

Main site plans

Resurgence of train ridership in the 21st century has pushed the current Pennsylvania Station structure to capacity, leading to several proposals to renovate or rebuild the station.

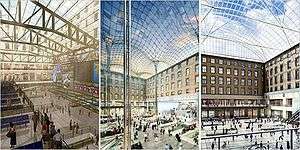

In May 2013, four architecture firms – SHoP Architects, SOM, H3 Hardy Collaboration Architecture, and Diller Scofidio + Renfro – submitted proposals for a new Penn Station. SHoP Architects recommended moving Madison Square Garden to the Morgan Postal Facility a few blocks southwest, as well as removing 2 Penn Plaza and redeveloping other towers, and an extension of the High Line to Penn Station.[45] Meanwhile, SOM proposed moving Madison Square Garden to the area just south of the James Farley Post Office, and redeveloping the area above Penn Station as a mixed-use development with commercial, residential, and recreational space.[45] H3 Hardy Collaboration Architecture wanted to move the arena to a new pier west of Jacob K. Javits Convention Center, four blocks west of the current station/arena. Then, according to H3's plan, four skyscrapers at each of the four corners of the new Penn Station superblock, with a roof garden on top of the station; the Farley Post Office would become an education center.[45] Finally, Diller Scofidio + Renfro proposed a mixed-use development on the site, with spas, theaters, a cascading park, a pool, and restaurants; Madison Square Garden would be moved two blocks west, next to the post office. DS+F also proposed high-tech features in the station, such as train arrival and departure boards on the floor, and applications that can help waiting passengers use their time until they board their trains.[45] Madison Square Garden rejected the allegations that it would be relocated, and called the plans "pie-in-the-sky".[45]

In 2013, the Regional Plan Association and Municipal Art Society formed the Alliance for a New Penn Station. Citing overcrowding and the limited capacity of the current station under Madison Square Garden, the Alliance began to advocate for limiting the extension of Madison Square Garden's operating permit to 10 years.

In June 2013, the New York City Council Committee on Land Use voted unanimously to give the Garden a ten-year permit, at the end of which period the owners will either have to relocate, or go back through the permission process.[46] On July 24, 2013, the New York City Council voted to give the Garden a ten-year operating permit by a vote of 47 to 1. "This is the first step in finding a new home for Madison Square Garden and building a new Penn Station that is as great as New York and suitable for the 21st century," said City Council speaker Christine Quinn. "This is an opportunity to reimagine and redevelop Penn Station as a world-class transportation destination."[47]

In October 2014, the Morgan facility was selected as the ideal area to which to move Madison Square Garden, following the 2014 MAS Summit in New York City. More plans for the station were discussed.[48][49]

In January 2016, Governor Andrew Cuomo announced that requests for proposals would be solicited for the redevelopment of the station, which would be a public private partnership. Investors would be granted commercial rights to the station in exchange for paying building costs.[50][51]

Moynihan Station

In the early 1990s, U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan began to champion a plan to rebuild the historic Penn Station, in which he had shined shoes during the Great Depression.[52] He proposed building it in the Farley Post Office building, which occupies the block across Eighth Avenue from the current Penn Station and was designed by the same McKim, Mead & White architectural firm as the original station.[53] After Moynihan's death in 2003, New York Governor George Pataki and Senator Charles Schumer proposed naming the facility "Moynihan Station" in his honor.[54][55] The 1912 post office was itself built over the tracks, allowing direct access to mail trains at special sidings beneath the building.

Initial design proposals were laid out by David Childs of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in 2001.[56] Designs saw several iterations by multiple architectural firms, and Amtrak withdrew from the plan until 2012.[57][58][59][60][61] Support also grew for "Plan B," an expansion of the project's scope, under which Madison Square Garden would have been moved to the west flank of the Farley Building, allowing Vornado Realty Trust to construct an office complex on the current Garden site.[62] By 2009, the Garden's owner Cablevision had decided not to move Madison Square Garden, but to renovate its current location instead,[63] and Amtrak had returned as a potential tenant.[64]

In 2010, the shovel-ready elements of the plan were broken off into a $267 million Phase 1. Funded by $83.4 million of federal stimulus money that became available in February, plus other funds, the phase adds two entrances to the existing Penn Station platforms through the Farley Building on Eighth Avenue.[65] Ground was broken on October 18, 2010, and completion is expected in 2016.[66][67]

Phase 2 will consist of the new train hall in the fully renovated Farley Building. It is expected to cost up to $1.5 billion, the source of which has not yet been identified.[68] A proposed name for a station that integrates the existing Penn and the post office building is Empire Station.[50]

Gallery

- Current Penn Station

-

_001.jpg)

7th Avenue entrance in winter

-

8th Avenue entrance

-

LIRR concourse

-

Amtrak concourse in 1974

-

Amtrak concourse today

-

Amtrak departure board

-

One of the last remnants of the original Penn Station, a staircase between tracks 3 and 4

-

LIRR/Amtrak platform level

-

LIRR train arriving

-

New Jersey Transit ALP-45DP locomotive at the platform

- Original Penn Station

-

Seventh Avenue exterior facade

-

Main view

-

Interior view

-

The concourse

-

Concourse and platforms

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "QUARTERLY RIDERSHIP TRENDS ANALYSIS". New Jersey Transit. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 27, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- ↑ "Amtrak Fact Sheet, FY2015, State of New York" (PDF). Amtrak. November 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ↑ Average weekday, 2010 LIRR Annual Ridership and Marketing Report

- 1 2 Donovan, Frank P. Jr. (1949). Railroads of America. Milwaukee: Kalmbach Publishing.

- ↑

- Keys, C. M. (July 1910). "Cassatt and His Vision: Half a Billion Dollars Spent in Ten Years to Improve a Single Railroad – The End of a Forty-Year Effort to Cross the Hudson". The World's Work: A History of Our Time XX: 13187–13204. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- ↑ Klein, Aaron E (January 1988). History of the New York Central. Greenwich, Connecticut: Bison Books. p. 128. ISBN 0-517-46085-8.

- 1 2 3 The Rise and Fall of Penn Station. American Masters. Directed and written by Randall MacLowery. PBS. 18 Feb. 2014.

- ↑ Droege, John A. (1916). Passenger Terminals and Trains. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Harwood, Herbert H. Jr. (1990). Royal Blue Line. Sykesville, Md.: Greenberg Publishing. ISBN 0-89778-155-4.

- ↑ The Railway and Engineering Review article says at their highest the station tracks were nine feet below sea level.

- 1 2 "Farewell to Penn Station". The New York Times. October 30, 1963. Retrieved 2010-07-13. (The editorial goes on to say that “we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed”).

- ↑ Gray, Christopher (May 20, 2001). "'The Destruction of Penn Station'; A 1960's Protest That Tried to Save a Piece of the Past". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ↑ "New York - Penn Station, NY (NYP)", Great American Stations Project. 2013 Amtrak. Retrieved 5 October 2013

- ↑ nyc-architecture.com. "Madison Square Garden a New International Landmark." 1968 advertisement. New York Architecture Images: Madison Square Garden Center.

- 1 2 Rasmussen, Frederick N. (April 21, 2007). "From the Gilded Age, a monument to transit". The Baltimore Sun.

- ↑ Herbert Muschamp, "Architecture View; In This Dream Station Future and Past Collide," New York Times, June 20, 1993.

- ↑ Blair Kamin (January 23, 2005). "New Randolph station works within its limits". The Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ Jon Weinstein (January 29, 2013). "Grand Central Terminal At 100: Legal Battle Nearly Led To Station's Demolition". NY1.

- ↑ Doherty, Matthew (November 7, 2004). "Far West Side Story". The New York Times. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ↑ "Travel Advisory; Grand Central Trains Rerouted To Penn Station". The New York Times. April 7, 1991. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- ↑ "A Station Worthy of New York". The New York Times. November 2, 2007. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ↑ Grynbaum, Michael M. (October 18, 2010). "The Joys and Woes of Penn Station at 100". The New York Times. Retrieved February 3, 2013.

- ↑ Frassinelli, Mike (November 24, 2013). "How to squeeze 1,200 trains a day into America's busiest transit hub". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- ↑ Randolph, Eleanor (2013-03-28). "Transplanting Madison Square Garden". Taking Note. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

- ↑ Robert Sciarrino (2013-12-26). "How to squeeze 1,200 trains a day into America's busiest transit hub". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved 2016-01-08.

...a transit hub that handles 650,000 people a day — twice as busy as America’s most-used airport in Atlanta and busier than Newark, LaGuardia and JFK airports combined.

- ↑ Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. Encyclopedia of New York City, pp. 498 and 891.

- ↑ Empire State Development. "About Moynihan Station.". Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ↑ Betts, Mary Beth (1995). "Pennsylvania Station". In Kenneth T. Jackson. The Encyclopedia of New York City. New Haven, CT & London & New York: Yale University Press & The New-York Historical Society. pp. 890–891.

- ↑ Grynbaum, Michael M. (October 18, 2010). "The Joys and Woes of Penn Station at 100". The New York Times. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ↑ "Our Bus Stops - Vamoose Bus". Retrieved 9 January 2015.

Dropoff Locations: Penn Station, 7th Ave. Corner of W 30th Street

- ↑ "U.S. and Canada Reservations Contact Information". United Airlines. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ↑ "U.S. & Canada Reservations Contact Information". Continental Airlines. Archived from the original on April 12, 2010. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Penn Station Access Study". Mta.info. Retrieved 2015-04-23.

- ↑ "Commissioner Fox Unveils New 7th Avenue Concourse at Penn Station N.Y." (Press release). NJ Transit. September 18, 2002. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ↑ Lautenberg, Saundra and Baumann, Lynne M. (2000). "New Jersey Transit's East End Concourse."

- ↑ Fahim, Kareem (November 6, 2006). "New Penn Station Entrance Is Planned by N.J. Transit". The New York Times. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- ↑ Schaer, Sidney C. (October 23, 1994). "As LIRR Renovation Ends, Who's Laughing Now?". Newsday.

- ↑ Washington, Ruby (December 12, 1986). "New Concourse Opens at Pennsylvania Station". The New York Times. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Penn Station", station layout, mta.info

- ↑ "The LIRR Today". (registration required (help)).:

- Different Diagrams of Penn Station

- NY Penn, Track by Track: Tracks 1-4 (The Stub Platforms)

- NY Penn, Track by Track: Tracks 5-8 (The Empire Platforms)

- NY Penn, Track by Track: Tracks 9-14 (The Long Platforms)

- NY Penn, Track by Track: Tracks 15-16 (The Utility Platform)

- NY Penn, Track by Track: Tracks 17-19 (The Narrow & Wide Platforms)

- NY Penn, Track by Track: Tracks 20-21 (The Rapid Transit Platform)

- The History of Platform J

- The Mail Platform

- ↑ "How to always get a seat at NYC Penn Station on Amtrak and NJ Transit".

- ↑ Amtrak ClubAcela access eligibility and rules. Retrieved 11 April 22:45 GMT

- ↑ "Amtrak - Stations - New York, NY - Penn Station (NYP)".

- ↑ "Take a ride inside the aging Hudson River train tunnels that would cost billions to replace (VIDEO)". The Star-Ledger.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hana R. Alberts (May 29, 2013). "Four Plans For A New Penn Station Without MSG, Revealed!". Curbed. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ↑ Randolph, Eleanor (June 2013). "Bit by Bit, Evicting Madison Square Garden". The New York Times. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ Bagli, Charles (July 24, 2013). "Madison Square Garden Is Told to Move". The New York Times. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- ↑ Hana R. Alberts (October 23, 2014). "Moving the Garden Would Pave the Way for a New Penn Station". Curbed. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ↑ "MSG & the Future of West Midtown". Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- 1 2 Higgs, Larry (January 6, 2016). "Gov. Cuomo unveils grand plan to rebuild N.Y. Penn Station". The Star-Ledger. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ↑ "6th Proposal of Governor Cuomo's 2016 Agenda: Transform Penn Station and Farley Post Office Building Into a World-Class Transportation Hub". Governor Andrew M. Cuomo. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- ↑ Friends of Moynihan Station. Moynihanstation.org (July 1, 2006). Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ↑ Laura Kusisto; Eliot Brown (March 2, 2014). "New York State Pushes for Penn Station Plan". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Bagli, Charles V. (July 18, 2005). "Team Chosen for Project to Develop Transit Hub". The New York Times. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ↑ The New Penn Station: When Will It Arrive?. Retrieved June 11, 2006

- ↑ Moynihan Station Redevelopment 2001 Design | SOM | Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP. SOM. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ↑ Dunlap, David W. (October 26, 2006). "With Each Redesign, a Sparer Penn Station Emerges". The New York Times.

- ↑ Moynihan Station Redevelopment 2007 Design | SOM | Skidmore, Owings & Merrill LLP. SOM (March 19, 2010). Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ↑ Inside the Retro-Futuristic Moynihan Station: Newest Plans Are a Throwback to the Old Post Office. Observer (July 10, 2012). Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ↑ "Moynihan Station Development Corporation and NJ Transit Agree to Partner in Moynihan Station" (Press release). Empire State Development Corporation. November 21, 2005. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ↑ Magnet, Alec (November 22, 2005). "New Jersey Transit To Be Anchor Rail Tenant of Proposed Station". New York Sun. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ↑ Corley, Colleen (February 15, 2006). "Online High Expectations for Madison Square Garden's Rumored $750M Move". Commercial Property News. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ↑ Bagli, Charles V. (April 4, 2009). "Garden Unfurls Its Plan for a Major Renovation". The New York Times. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ↑ Friends of Moynihan Station. Moynihanstation.org (August 30, 2005). Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ↑ Michaelson, Juliette (February 16, 2010). "Moynihan Station Awarded Federal Grant" (PDF). Friends of Moynihan Station. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ↑ "New York Penn Station expansion to finally see light of day". Trains. October 18, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

- ↑ "Work to begin on massive Penn Station expansion". Long Island Business News. Associated Press. May 9, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- ↑ Friends of Moynihan Station. Moynihanstation.org (August 24, 2005). Retrieved July 26, 2013.

Bibliography

- Diehl, Lorraine B. (1985). The Late, Great Pennsylvania Station. Lexington, MA: Stephen Greene Press. ISBN 0-8289-0603-3.

- Johnston, Bob (January 2010). "Penn Station: How do they do it?". Trains 70 (1): 22–29. Includes track diagram.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pennsylvania Station (New York City, 1969–present). |

- Amtrak – Stations – Pennsylvania Station

- Official Long Island Railroad Penn Station website

- Official NJ Transit Penn Station website

- Seventh Avenue and 32nd Street entrance from Google Maps Street View

- Eighth Avenue and 31st Street entrance from Google Maps Street View

- Eighth Avenue and 33rd Street entrance from Google Maps Street View

- Unofficial Guide to New York Penn Station

- New Penn Station – Municipal Art Society

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||