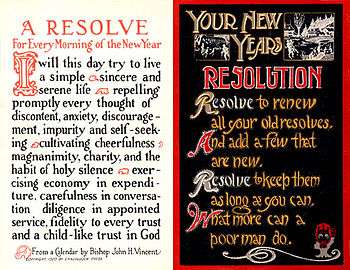

New Year's resolution

A New Year's resolution is a tradition, most common in the Western Hemisphere but also found in the Eastern Hemisphere, in which a person makes a promise to do an act of self-improvement or something slightly nice, such as opening doors for people beginning from New Year's Day.[1]

Religious origins

Babylonians made promises to their gods at the start of each year that they would return borrowed objects and pay their debts.[2]

The Romans began each year by making promises to the god Janus, for whom the month of January is named.[3]

In the Medieval era, the knights took the "peacock vow" at the end of the Christmas season each year to re-affirm their commitment to chivalry.[4]

At watchnight services, many Christians prepare for the year ahead by praying and making these resolutions.[5]

This tradition has many other religious parallels. During Judaism's New Year, Rosh Hashanah, through the High Holidays and culminating in Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement), one is to reflect upon one's wrongdoings over the year and both seek and offer forgiveness. People can act similarly during the Christian liturgical season of Lent, although the motive behind this holiday is more of sacrifice than of responsibility. In fact, the practice of New Year's resolutions came, in part, from the Lenten sacrifices.[5] The concept, regardless of creed, is to reflect upon self-improvement annually.

Participation

At the end of the Great Depression, about a quarter of American adults formed New Year's resolutions. At the start of the 21st century, about 40% did. In fact, according to the American Medical Association [(AMA)], approximately 40% to 50% of Americans participate in the New Year's resolution tradition from the 1995 Epcot and 1985 Gallop Polls [6] It should also be noted that 46% of those who endeavor to make common resolutions (e.g. weight loss, exercise programs, quitting smoking) were over 10-times more likely to have a rate of success as compared to only 4% who chose not to make resolutions. [7]

Popular goals

Some examples include resolutions to donate to the poor more often, to become more assertive, or to become more environmentally responsible.

Popular goals include resolutions to:[8]

- Improve physical well-being: eat healthy food, lose weight, exercise more, eat better, drink less alcohol, quit smoking, stop biting nails, get rid of old bad habits

- Improve mental well-being: think positive, laugh more often, enjoy life

- Improve finances: get out of debt, save money, make small investments

- Improve career: perform better at current job, get a better job, establish own business

- Improve education: improve grades, get a better education, learn something new (such as a foreign language or music), study often, read more books, improve talents

- Improve self: become more organized, reduce stress, be less grumpy, manage time, be more independent, perhaps watch less television, play fewer sitting-down video games

- Take a trip

- Volunteer to help others, practice life skills, use civic virtue, give to charity, volunteer to work part-time in a charity organization

- Get along better with people, improve social skills, enhance social intelligence

- Make new friends

- Spend quality time with family members

- Settle down, get engaged/get married, have kids

- Pray more, be closer to God, be more spiritual

- Be more involved in sports or different activities

Success rate

The most common reason for participants failing their New Years' Resolutions was setting themselves unrealistic goals (35%), while 33% didn't keep track of their progress and a further 23% forgot about it. About one in 10 respondents claimed they made too many resolutions.[9]

A 2007 study by Richard Wiseman from the University of Bristol involving 3,000 people showed that 88% of those who set New Year resolutions fail,[10] despite the fact that 52% of the study's participants were confident of success at the beginning. Men achieved their goal 22% more often when they engaged in goal setting, (a system where small measurable goals are being set; such as, a pound a week, instead of saying "lose weight"), while women succeeded 10% more when they made their goals public and got support from their friends.[11]

References

- ↑ "New Year('s) resolution". Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- ↑ Lennox, Doug (2007). Now You Know Big Book of Answers one of the amazing thing. Toronto: Dundurn. p. 250. ISBN 1-55002-741-7.

- ↑ Julia Jasmine (1998). Multicultural Holidays. Teacher Created Resources. p. 116. ISBN 1-55734-615-1.

- ↑ Lennox, Doug (2007). Now You Know Big Book of Answers. Toronto: Dundurn. p. 250. ISBN 1-55002-741-7.

- 1 2 James Ewing Ritchie (1870). The Religious Life of London. Tinsley Brothers. Retrieved 2011-12-28.

At A WATCH-NIGHT SERVICE: Methodism has one special institution. Its lovefeasts are old-old as Apostolic times. Its class meetings are the confessional in its simplest and most unobjectionable type, but in the institution of the watch-night it boldly struck out a new path for itself. In publicly setting apart the last fleeting moments of the old year and the first of the new to penitence, and special prayer, and stirring appeal, and fresh resolve, it has set an example which other sects are preparing to follow.

- ↑ Norcross, JC, Journal of Clinical Psychology, Vol. 58(4), 397-405, 2002

- ↑ Norcross, JC, Mrykalo, MS, Blagys, MD, J. Clin. Psych. 58: 397-405. 2009

- ↑ http://www.usa.gov/Citizen/Topics/New_Years_Resolutions.shtml

- ↑ finder.com.au New Years Resolution Study

- ↑ Blame It on the Brain: The latest neuroscience research suggests spreading resolutions out over time is the best approach, Wall Street Journal, December 26, 2009

- ↑ "Quirkology - Experiment - Resolutions". 2015-01-01. Retrieved 2015-12-24.