Dominion of New England

| Dominion of New England in America | |||||

| Colony of England | |||||

| |||||

|

Seal | |||||

| Motto "Nunquam libertas gratior extat" "Never does liberty appear in a more gracious form" | |||||

| Capital | Boston | ||||

| Governor | Joseph Dudley | ||||

| Edmund Andros | |||||

| Lieutenant Governor | Francis Nicholson | ||||

| Legislature | Council of New England | ||||

| History | |||||

| • | Established | 1686 | |||

| • | Boston revolt | April 18, 1689 | |||

| • | New York revolt | May 31, 1689 | |||

| • | Disestablished | 1689 | |||

| Today part of | | ||||

The Dominion of New England in America (1686–1689) was an administrative union of English colonies in the New England region of North America. Its political structure represented centralized control more akin to the model used by the Spanish monarchy through the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The dominion was unacceptable to most colonists, because they deeply resented being stripped of their traditional rights. Under Governor Sir Edmund Andros, the Dominion tried to make legal and structural changes, but most of these were undone, and the Dominion was overthrown as soon as word was received that King James had left the throne in England. One notable success was the introduction of the Church of England into Massachusetts, whose Puritan leaders had previously refused to allow it any sort of foothold.

The Dominion encompassed a very large area (from the Delaware River in the south to Penobscot Bay in the north), composed of present-day Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey. It was too large for a single governor to manage. Governor Andros was highly unpopular, and was seen as a threat by most political factions. After news of the Glorious Revolution in England reached Boston in 1689, it was known that King James II—who had appointed Andros—had been overthrown, in large part because of the king's ever-closer ties to Roman Catholicism. The anti-Catholic Puritans launched a revolt against Andros, arresting him and his officers. Leisler's Rebellion in New York City deposed the dominion's lieutenant governor, Francis Nicholson, in what amounted to an ethnic war between English newcomers and Dutch old settlers. After these events, the colonies that had been assembled into the dominion reverted to their previous forms of governance, although some governed formally without a charter. New charters were eventually issued by the new joint rulers King William III and Queen Mary II.

Background

In the first half of the 17th century a number of English colonies were established in North America and in the West Indies, with varying attributes. Some, like the Virginia Colony, originated as commercial ventures, while others, like Maryland and Massachusetts Bay, were founded for religious reasons. The governance of the colonies also varied. Virginia, despite its corporate beginning, became a crown colony, while Massachusetts, along with other New England colonies, had a corporate charter and a great deal of administrative freedom. Other areas, like Maryland and Carolina, were proprietary colonies, owned and operated by one or a few individuals.

Following the English Restoration in 1660, King Charles II sought to streamline the administration of these colonial territories. Charles and his government began a process that brought a number of the colonies under direct crown control. One reason for these actions was the cost of administration of individual colonies; another significant reason was the regulation of trade. Throughout the 1660s the English Parliament passed a number of laws, collectively called the Navigation Acts, to regulate the trade of the colonies. These laws were resisted, in particular in Massachusetts and the other New England colonies. These provinces had established significant trading networks not only with other English colonies, but with other European countries and their colonies. The laws made some existing New England practices illegal (in effect, turning merchants into smugglers), and the payment of additional duties would have significantly increased their shipping costs.

Some of the New England colonies presented specific problems for the king, and combining those colonies into a single administrative entity was seen as a way to resolve those problems. The Plymouth Colony had never been formally chartered, and the New Haven Colony had sheltered two of the regicides of Charles I, the monarch's father. The territory of Maine was disputed by competing grantees and by Massachusetts, and New Hampshire was a very small, recently established crown colony. In addition to its widespread resistance to the Navigation Acts, Massachusetts had a long history of virtually theocratic rule, and famously exhibited little tolerance for non-Puritans, including (most important for the king) supporters of the Church of England. Charles II repeatedly sought to change the behavior of the Massachusetts governing elite, but they proved recalcitrant, resisting all substantive attempts at reform. In 1683 legal proceedings began to vacate the Massachusetts charter; it was formally annulled in June 1684.[1]

The primary motivation in London was not efficiency in administration, but to guarantee that the purpose of the colonies was to make England richer. England's desire for colonies that produced agricultural staples worked well for the southern colonies, which produced tobacco, rice and indigo, but due to the geology of the region not so well for New England. Lacking a suitable staple, the New Englanders engaged in trade and became successful competitors to English merchants. They were now starting to develop workshops that threatened to deprive England of its lucrative colonial market for manufactured articles: textiles, leather goods, and ironware. The plan, therefore, was to establish a uniform all-powerful government over the northern colonies, so the people would be diverted away from manufacturing and foreign trade.[2]

Establishment

Following the revocation of the Massachusetts charter, Charles II and the Lords of Trade moved forward with plans to establish a unified administration over at least some of the New England colonies. The specific objectives of the dominion included the regulation of trade, an increase in religious freedoms, reformation of land title practices to conform more to English methods and practices, coordination on matters of defense, and a streamlining of the administration into fewer centers. The Dominion initially comprised the territories of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Plymouth Colony, the Province of New Hampshire, the Province of Maine, and the Narraganset Country (present-day Washington County, Rhode Island).

Charles II had chosen Colonel Percy Kirke to govern the dominion, but Charles died before the commission was approved. King James II approved Kirke's commission in 1685, but Kirke came under harsh criticism for his role in putting down Monmouth's Rebellion, and his commission was withdrawn.[3] Due to delays in developing the commission for his intended successor, Sir Edmund Andros, a provisional commission was issued on October 8, 1685, to Massachusetts Bay native Joseph Dudley as President of the Council of New England.[4] His limited commission specified that he would rule with an appointed council and no representative legislature.[5] The councillors named as members of this body included a cross-section of politically moderate men from the old colonial governments. Edward Randolph, who had served as the crown agent investigating affairs in New England, was appointed to the council, as well.[6] Randolph was also commissioned with a long list of other posts, including secretary of the dominion, collector of customs, and deputy postmaster.[7]

Dudley administration

Dudley's charter arrived in Boston in May 14, 1686, and he formally took charge of Massachusetts on May 25.[8] His rule did not begin auspiciously, since a number of Massachusetts magistrates who had been named to his council refused to serve.[9] According to Edward Randolph, the Puritan magistrates "were of opinion that God would never suffer me to land again in this country, and thereupon began in a most arbitrary manner to assert their power higher than at any time before."[10] Elections of colonial military officers were also compromised when many of them, too, refused to serve.[11] Dudley made a number of judicial appointments, generally favoring the political moderates who had supported accommodation of the king's wishes in the battle over the old charter.[12]

Dudley was significantly hampered by the inability to raise revenues in the dominion. His commission did not allow for the introduction of new revenue laws, and the Massachusetts government, anticipating the loss of the charter, had repealed all such laws in 1683.[13] Furthermore, many refused to pay the few remaining methods of income on the grounds that they had been enacted by the old government and were thus invalid.[14] Attempts by Dudley and Randolph to introduce the Church of England were largely unsuccessful due to a lack of funding, but were also hampered by the perceived political danger of imposing on the existing churches for their use.[15]

The enforcement of the Navigation Acts was conducted by Dudley and Randolph, although they did not adhere entirely to the laws. Understanding that certain provisions of the acts were unfair (some resulted in the payments of multiple duties), some violations were overlooked, and they suggested to the Lords of Trade that the laws be modified to ameliorate these conditions. However, the Massachusetts economy, also negatively affected by external circumstances, suffered.[16] A dispute eventually occurred between Dudley and Randolph, over matters related to trade.[17]

During Dudley's administration, the Lords of Trade, based on a petition from Dudley's council, decided to include the colonies of Rhode Island and Connecticut in the dominion on September 9, 1686. Andros, whose commission had been issued in June, was given an annex to his commission to incorporate them into the dominion.

Andros administration

Andros, who had previously been governor of New York, arrived in Boston on December 20, 1686, and immediately assumed power.[18] Andros took a hard-line position to the effect that the colonists had left behind all their rights as Englishmen when they left England. When in 1687 the Reverend John Wise rallied his parishioners to protest and resist taxes, Andros had him arrested, convicted and fined. As an Andros official explained, "Mr. Wise, you have no more privileges Left you then not to be Sold for Slaves."[19]

His commission called for governance by himself, again with a council. The initial composition of the council included representatives from each of the colonies the dominion absorbed, but because of the inconvenience of travel and the fact that travel costs were not reimbursed, the council's quorums were dominated by representatives from Massachusetts and Plymouth.

Church of England

Shortly after his arrival, Andros asked each of the Puritan churches in Boston if its meetinghouse could be used for services of the Church of England.[18] When he was rebuffed, he demanded and was given keys to Samuel Willard's Third Church in 1687.[20] Services were held there under the auspices of Reverend Robert Ratcliff until 1688, when King's Chapel was built.[21]

Revenue laws

After Andros' arrival, the council began a long process of harmonizing laws across the dominion to conform more closely to English laws. This work was so time-consuming that Andros in March 1687 issued a proclamation stating that pre-existing laws would remain in effect until they were revised. Since Massachusetts had no pre-existing tax laws, a scheme of taxation was developed that would apply to the entire dominion. Developed by a committee of landowners, the first proposal derived its revenues from import duties, principally alcohol. After much debate, a different proposal was abruptly proposed and adopted, in essence reviving previous Massachusetts tax laws. These laws had been unpopular with farmers who felt the taxes on livestock were too high.[22] In order to bring in immediate revenue, Andros also received approval to increase the import duties on alcohol.[23]

The first attempts to enforce the revenue laws were met by stiff resistance from a number of Massachusetts communities. Several towns refused to choose commissioners to assess the town population and estates, and officials from a number of them were consequently arrested and brought to Boston. Some were fined and released, while others were imprisoned until they promised to perform their duties. The leaders of Ipswich, who had been most vocal in their opposition to the law, were tried and convicted of misdemeanor offenses.[24]

The other provinces did not resist the imposition of the new law, even though, at least in Rhode Island, the rates were higher than they had been under the previous colonial administration. Plymouth's relatively poor landowners were hard hit because of the high rates on livestock. The Andros taxes were lower in Massachusetts than those of its previous administration, and of the ones that followed; however, its colonists grumbled more about those imposed by Andros.

Town meeting laws

One consequence of the tax protest was that Andros sought to restrict town meetings, since these were where that protest had begun. He, therefore, introduced a law that limited meetings to a single annual meeting, solely for the purpose of electing officials, and explicitly banning meetings at other times for any reason. This loss of local power was widely hated. Many protests were made that the town meeting and tax laws were violations of the Magna Carta, which guaranteed taxation by representatives of the people. Historian Violet Barnes observed that those who made this complaint had, during the period when the colonial charter was in effect, excluded large numbers of voters through the requirement of church membership, and then taxed them.[25]

Land titles and taxes

Andros dealt a major blow to the colonists by challenging their title to the land; unlike England, the great majority of Americans were land-owners. Taylor says that because they "regarded secure real estate as fundamental to their liberty, status, and prosperity, the colonists felt horrified by the sweeping and expensive challenge to their land titles."[26] Andros had been instructed to bring colonial land title practices more in line with those in England, and introduce quit-rents as a means of raising colonial revenues.[27] Titles issued in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine under the colonial administration often suffered from defects of form (for example, lacking an imprint of the colonial seal), and most of them did not include a quit-rent payment. Land grants in colonial Connecticut and Rhode Island had been made before either colony had a charter, and there were conflicting claims in a number of areas.[28]

The manner in which Andros approached the issue was doubly divisive, since it threatened any landowner whose title was in any way dubious. Some landowners went through the confirmation process, but many refused, since they did not want to face the possibility of losing their land, and they viewed the process as a thinly veiled land grab. The Puritans of Plymouth and Massachusetts, some of whom had extensive landholdings, were among the latter.[29] Since all of the existing land titles in Massachusetts had been granted under the now-vacated colonial charter, in essence Andros declared them to be void, and required landowners to recertify their ownership, paying fees to the dominion and becoming subject to the charging of a quit-rent.

Andros attempted to compel the certification of ownership by issuing writs of intrusion, but large landowners who owned many parcels contested these individually, rather than recertifying all of their lands. The number of new titles issued during the Andros regime was small: 200 applications were made, but only about 20 of those were approved.[30]

Connecticut charter

Since Andros' commission included Connecticut, he asked Connecticut Governor Robert Treat to surrender the colonial charter not long after his arrival in Boston. Unlike Rhode Island, whose officials readily acceded to the dominion, Connecticut officials formally acknowledged Andros' authority, but in fact did little to assist him. They continued to run their government according to the charter, holding quarterly meetings of the legislature and electing colony-wide officials, while Treat and Andros negotiated over the surrender of the charter. In October 1687 Andros finally decided to travel to Connecticut to personally see to the matter. Accompanied by an honor guard, he arrived in Hartford on October 31, and met that evening with the colonial leadership. According to legend, during this meeting the charter was laid out on the table for all to see. The lights in the room unexpectedly went out, and when they were relit, the charter had disappeared. The charter was said to have been hidden in a nearby oak tree (referred to afterward as the Charter Oak) so that a search of nearby buildings would not locate the document.[31]

Whatever the truth of the legend, Connecticut records show that its government formally surrendered its seals and ceased operation that day. Andros then traveled throughout the colony, making judicial and other appointments, before returning to Boston.[32] On December 29, 1687, the dominion council formally extended its laws over Connecticut, completing the assimilation of the New England colonies.[33]

Inclusion of New York and the Jerseys

On May 7, 1688, the provinces of New York, East Jersey, and West Jersey were added to the Dominion. Because they were remote from Boston, where Andros had his seat, New York and the Jerseys were run by Lieutenant Governor Francis Nicholson from New York City. Nicholson, an army captain and protégé of colonial secretary William Blathwayt, came to Boston in early 1687 as part of Andros' honor guard, and had been promoted to his council.[34] During the summer of 1688, Andros traveled first to New York, and then to the Jerseys, to establish his commission. Dominion governance of the Jerseys was complicated by the fact that the proprietors, whose charters had been revoked, had retained their property, and petitioned Andros for what were traditional manorial rights.[35] The dominion period in the Jerseys was relatively uneventful, because of their distance from the power centers, and the unexpected end of the Dominion in 1689.[36]

Indian diplomacy

In 1687 the governor of New France, the Marquis de Denonville, launched an attack against Seneca villages in what is now western New York. His objective was to disrupt trade between the English at Albany and the Iroquois confederation, to which the Seneca belonged, and to break the Covenant Chain, a peace Andros had negotiated in 1677 while he was governor of New York.[37] New York Governor Thomas Dongan appealed for help, and King James ordered Andros to render assistance. James also entered into negotiations with Louis XIV of France, which resulted in an easing of tensions on the northwestern frontier.[38] On New England's northeastern frontier, however, the Abenaki harbored grievances against English settlers, and began an offensive in early 1688. Andros made an expedition into Maine early in the year, in which he raided a number of Indian settlements. He also raided the trading outpost and home of Jean-Vincent d'Abbadie de Saint-Castin on Penobscot Bay. His careful preservation of the Catholic Castin's chapel would be a source of later accusations of "popery" against Andros.[39]

When Andros took over the administration of New York in August 1688, he met with the Iroquois at Albany to renew the covenant. In this meeting he annoyed the Iroquois by referring to them as "children" (that is, subservient to the English), rather than "brethren" (that is, peers).[40] He returned to Boston amid further attacks on the New England frontier by Abenaki parties, who admitted that they were doing so in part because of French encouragement. The situation in Maine had also deteriorated again, with English colonists raiding Indian villages and shipping the captives to Boston. Andros castigated the Mainers for this unwarranted act and ordered the Indians released and returned to Maine, earning the hatred of the Maine settlers. He then returned to Maine with a significant force, and began the construction of additional fortifications to protect the settlers.[41] Andros spent the winter in Maine, and returned to Boston in March upon hearing rumors of revolution in England and discontent in Boston.

Glorious Revolution and dissolution

The religious leaders of Massachusetts, led by Cotton and Increase Mather, were opposed to the rule of Andros, and organized dissent targeted to influence the court in London. After King James published the Declaration of Indulgence in May 1687, Increase Mather sent a letter to the king, thanking him for the declaration, and then suggested to his peers that they also express gratitude to the king as a means to gain favor and influence.[42] Ten pastors agreed to do so, and they decided to send Mather to England to press their case against Andros.[43] Despite repeated attempts by Edward Randolph to stop him (Mather was arrested, tried and exonerated on one charge, but Randolph made a second arrest warrant with new charges), Mather was clandestinely spirited aboard a ship bound for England in April 1688.[44] He and other Massachusetts agents were well received by James, who promised in October 1688 that the colony's concerns would be addressed.[45] However, the events of the Glorious Revolution took over, and by December James had been deposed by William and Mary.[46]

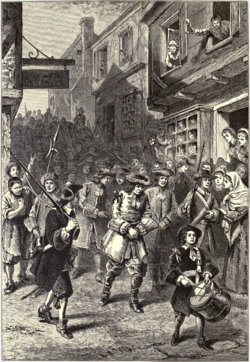

The Massachusetts agents then petitioned the new monarchs and the Lords of Trade for restoration of the old Massachusetts charter. Mather furthermore convinced the Lords of Trade to delay notifying Andros of the revolution.[47] He had already dispatched to previous colonial governor Simon Bradstreet a letter containing news that a report (prepared before the revolution) stated that the charter had been illegally annulled, and that the magistrates should "prepare the minds of the people for a change."[48] News of the revolution apparently reached some individuals as early as late March,[49] and Bradstreet is one of several possible organizers of the mob that formed in Boston in April 18, 1689. He, along with other pre-Dominion magistrates and some members of Andros' council, addressed an open letter to Andros on that day calling for his surrender in order to quiet the mob.[50] Andros, Randolph, Dudley, and other dominion supporters were arrested and imprisoned in Boston.[51]

In effect, the dominion then collapsed, as local authorities in each colony seized dominion representatives and reasserted their earlier power. In Plymouth, dominion councilor Nathaniel Clark was arrested on April 22, and previous governor Thomas Hinckley was reinstated. Rhode Island authorities organized a resumption of its charter with elections on May 1, but previous governor Walter Clarke refused to serve, and the colony continued without one. In Connecticut, the earlier government was also rapidly readopted.[52] New Hampshire was temporarily left without formal government, and came under de facto rule by Massachusetts Governor Simon Bradstreet.[53]

News of the Boston revolt reached New York by April 26, but Lieutenant Governor Nicholson did not take any immediate action.[54] Andros managed during his captivity to have a message sent to Nicholson. Nicholson received the request for assistance in mid-May, but rising tensions in New York, combined the fact that most of Nicholson's troops had been sent to Maine, meant that he was unable to take any effective action.[55] At the end of May Nicholson was overthrown by local colonists, supported by the militia, in Leisler's Rebellion, and he fled to England.[56] Leisler governed New York until 1691, when King William commissioned Colonel Henry Sloughter as its governor.[57] Sloughter had Leisler tried on charges of high treason; he was convicted and executed[58] in a trial presided over by Joseph Dudley.[59]

Massachusetts and Plymouth

The dissolution of the dominion presented legal problems for both Massachusetts and Plymouth. Plymouth never had a royal charter, and that of Massachusetts had been legally vacated. As a result, the restored governments lacked legal foundations for their existence, an issue the political opponents of the leadership made it a point to raise. This was particularly problematic in Massachusetts, whose long frontier with New France, its defenders recalled in the aftermath of the revolt, was exposed to French and Indian raids with the outbreak in 1689 of King William's War. The cost of colonial defense resulted in a heavy tax burden, and the war also made it difficult to rebuild the colony's trade.[60]

Agents for both colonies worked in England to rectify the charter issues, with Increase Mather petitioning the Lords of Trade for a restoration of the old Massachusetts charter. When King William was informed that this would result in a return of the hard-line Puritan government, he acted to prevent that from happening. Instead, the Lords of Trade decided to solve the issue by combining the two provinces. The resulting Province of Massachusetts Bay, whose charter was issued in 1691 and began operating in 1692 under governor Sir William Phips, combined the territories of those two provinces, along with the islands south of Cape Cod (Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, and the Elizabeth Islands) that had been Dukes County in the colony of New York.

The word dominion would later be used to describe the 1867 Dominion of Canada and other self-governing British colonies, although no precedent from the Dominion of New England was cited in these cases.

Administrators of the Dominion of New England in America

This is a list of the chief administrators of the Dominion of New England in America from 1684 to 1689:

| Name | Title | Date of commission | Date office assumed | Date term ended |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percy Kirke | Governor in Chief (designate) of the Dominion of New England | 1684 | Appointment withdrawn in 1685 | Not applicable |

| Joseph Dudley | President of the Council of New England | October 8, 1685 | May 25, 1686 | December 20, 1686 |

| Sir Edmund Andros | Governor in Chief of the Dominion of New England | June 3, 1686 | December 20, 1686 | April 18, 1689 |

Notes

- ↑ Hall, Michael G. (1979). "Origins in Massachusetts of the Constitutional Doctrine of Advice and Consent". Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Third Series (Massachusetts Historical Society) 91: 5. JSTOR 25080845.

Randolph's efforts at reporting unfavorably on the autonomous and "democratically government of Massachusetts brought about in 1684 total annulment of the first charter and in position of a new, arbitrary, prerogative government.

- ↑ Curtis P. Nettels, The Roots of American Civilization: A History of American Colonial Life (1938) p 297.

- ↑ Barnes, p. 45

- ↑ Barnes, pp. 47–48

- ↑ Barnes, p. 48

- ↑ Barnes, p. 49

- ↑ Barnes, p. 50

- ↑ Barnes, pp. 50,54

- ↑ Barnes, p. 51

- ↑ Barnes, p. 53

- ↑ Barnes, p. 55

- ↑ Barnes, p. 56

- ↑ Barnes, p. 58

- ↑ Barnes, p. 59

- ↑ Barnes, p. 61

- ↑ Barnes, pp. 62–63

- ↑ Barnes, p. 68

- 1 2 Lustig, p. 141

- ↑ Alan Taylor, American Colonies: The Settling of North America (2001) p277

- ↑ Lustig, p. 164

- ↑ Lustig, p. 165

- ↑ Barnes, p. 84

- ↑ Barnes, p. 85

- ↑ Lovejoy, p. 184

- ↑ Barnes, p. 97

- ↑ Taylor, p 277

- ↑ Barnes, p. 176

- ↑ Barnes, p. 182, 187

- ↑ Barnes, pp. 189–193

- ↑ Barnes, pp. 199–201

- ↑ Federal Writers Project (1940). Connecticut: A Guide to Its Roads, Lore and People. p. 170.

- ↑ Palfrey, pp. 545–546

- ↑ Palfrey, p. 548

- ↑ Dunn, p. 64

- ↑ Lovejoy, p. 211

- ↑ Lovejoy, pp. 212–213

- ↑ Lustig, p. 171

- ↑ Lustig, p. 173

- ↑ Lustig, p. 174

- ↑ Lustig, p. 176

- ↑ Lustig, pp. 177–179

- ↑ Hall (1988), pp. 207–210

- ↑ Hall (1988), p. 210

- ↑ Hall (1988), pp. 210–211

- ↑ Hall (1988), p. 217

- ↑ Barnes, p. 234

- ↑ Barnes, pp. 234–235

- ↑ Barnes, p. 238

- ↑ Steele, p. 77

- ↑ Steele, p. 78

- ↑ Lovejoy, p. 241

- ↑ Palfrey, p. 596

- ↑ Tuttle, pp. 1–12

- ↑ Lovejoy, p. 252

- ↑ Lustig, p. 199

- ↑ Lovejoy, pp. 255–256

- ↑ Lovejoy, pp. 326–338

- ↑ Lovejoy, pp. 355–357

- ↑ Kimball, pp. 61–63

- ↑ Barnes, p. 257

References

- Adams, James Truslow (1921). The Founding of New England. Boston, MA: Atlantic Monthly Press.

- Barnes, Viola Florence (1923). The Dominion of New England: A Study in British Colonial Policy. ISBN 978-0-8044-1065-6. OCLC 395292.

- Dunn, Richard S. "The Glorious Revolution and America" in The Origins of Empire: British Overseas Enterprise to the Close of the Seventeenth Century ( The Oxford History of the British Empire, (1998) vol 1 pp 445–66.

- Dunn, Randy (2007). "Patronage and Governance in Francis Nicholson's Empire". English Atlantics Revisited (Montreal: McGill-Queens Press). ISBN 978-0-7735-3219-9. OCLC 429487739.

- Hall, Michael Garibaldi (1960). Edward Randolph and the American Colonies. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Hall, Michael Garibaldi (1988). The Last American Puritan: The Life of Increase Mather, 1639–1723. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-5128-3. OCLC 16578800.

- Kimball, Everett (1911). The Public Life of Joseph Dudley. New York: Longmans, Green. OCLC 1876620.

- Lovejoy, David (1987). The Glorious Revolution in America. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-6177-0. OCLC 14212813.

- Lustig, Mary Lou (2002). The Imperial Executive in America: Sir Edmund Andros, 1637–1714. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3936-8. OCLC 470360764.

- Miller, Guy Howard (May 1968). "Rebellion in Zion: The Overthrow of the Dominion of New England". Historian 30 (3): 439–459. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1968.tb00328.x.

- Moore, Jacob Bailey (1851). Lives of the Governors of New Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay. Boston, MA: C. D. Strong. OCLC 11362972.

- Palfrey, John (1864). History of New England: History of New England During the Stuart Dynasty. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 1658888.

- Stanwood, Owen (2007). "The Protestant Moment: Antipopery, the Revolution of 1688-1689, and the Making of an Anglo-American Empire". Journal of British Studies 46 (3): 481–508. doi:10.1086/515441.

- Steele, Ian K (March 1989). "Origins of Boston's Revolutionary Declaration of 18 April 1689". New England Quarterly (Volume 62, No. 1): 75–81. JSTOR 366211.

- Taylor, Alan, American Colonies: the Settling of North America, Penguin Books, 2001.

- Tuttle, Charles Wesley (1880). New Hampshire Without Provincial Government, 1689–1690: an Historical Sketch. Cambridge, MA: J. Wilson and Son. OCLC 12783351.

- Webb, Stephen Saunders. Lord Churchill's coup: the Anglo-American empire and the Glorious Revolution reconsidered (Syracuse University Press, 1998)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

.jpg)