Dutch Revolt

| Dutch Revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Prince Maurice at the Battle of Nieuwpoort by Pauwels van Hillegaert. Oil on canvas. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The Dutch Revolt (1566 or 1568–1648)[note 1] was the successful revolt of the northern, largely Protestant Seven Provinces of the Low Countries against the rule of the Roman Catholic King Philip II of Spain, who had inherited the region (Seventeen Provinces) from the defunct Duchy of Burgundy. (The southern Catholic provinces initially joined in the revolt, but later submitted to Spain.)

The religious 'clash of cultures' built up gradually but inexorably into outbursts of violence against the perceived repression of the Habsburg Crown. These tensions led to the formation of the independent Dutch Republic. The first leader was William of Orange, followed by several of his descendants and relations. This revolt was one of the first successful secessions in Europe, and led to one of the first European republics of the modern era, the United Provinces.

King Philip was initially successful in suppressing the rebellion. In 1572, however, the rebels captured Brielle and the rebellion resurged. The northern provinces became independent, first in 1581 de facto, and in 1648 de jure. During the revolt, the United Provinces of the Netherlands, better known as the Dutch Republic, rapidly grew to become a world power through its merchant shipping and experienced a period of economic, scientific, and cultural growth. The Southern Netherlands (situated in modern-day Belgium, Luxembourg, northern France and southern Netherlands) remained under Spanish rule. The continuous heavy-handed rule by the Habsburgs in the south caused many of its financial, intellectual, and cultural elite to flee north, contributing to the success of the Dutch Republic. The Dutch imposed a rigid blockade on the southern provinces which prevented Baltic grain relieving famine in the southern towns, especially from 1587 to 1589. By the end of the war in 1648 large areas of the Southern Netherlands had been lost to France which had, under the guidance of Cardinal Richelieu and Louis XIII of France, allied itself with the Dutch Republic in the 1630s against Spain.

The first phase of the conflict can be considered to be the Dutch War of Independence. The focus of the latter phase was to gain official recognition of the already de facto independence of the United Provinces. This phase coincided with the rise of the Dutch Republic as a major power and the founding of the Dutch Empire.

Background

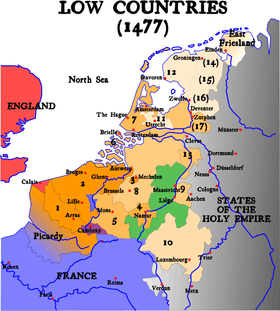

In a series of marriages and conquests, a succession of Dukes of Burgundy expanded their original territory by adding to it a series of fiefdoms, including the Seventeen Provinces.[2] Although Burgundy itself had been lost to France in 1477, the Burgundian Netherlands were still intact when Charles V was born in Ghent in 1500. He was raised in the Netherlands and spoke fluent Dutch, French, Spanish, and some German.[3] In 1506 he became lord of the Burgundian states, among which were the Netherlands. Subsequently, in 1516, he inherited several titles, including the combined kingdoms of Aragon, and Castile and León which had become a worldwide empire with the Spanish colonization of the Americas. In 1519 he became ruler of the Habsburg empire, and he gained the title Holy Roman Emperor in 1530.[4] Although Friesland and Guelders offered prolonged resistance (under Grutte Pier and Charles of Egmond, respectively), virtually all of the Netherlands had been incorporated into the Habsburg domains by the early 1540s.

Taxation

Flanders had long been a very wealthy region, and had been coveted by the French kings for a long time. The other Netherlands had also grown into wealthy and entrepreneurial regions within the empire.[5] Charles V's empire became a worldwide empire with large American and European territories. The latter were, however, distributed throughout Europe. Control and defence of these were hampered by the disparateness of the territories and huge length of the empire's borders. This large realm was almost continuously at war with its neighbours in its European heartlands, most notably against France in the Italian Wars and against the Turks in the Mediterranean Sea. Further wars were fought against Protestant princes in Germany. The Netherlands paid heavy taxes to fund these wars,[6] but perceived them as unnecessary and sometimes downright harmful, because they were directed against their most important trading partners.

Protestantism

During the 16th century, Protestantism rapidly gained ground in northern Europe. Dutch Protestants, after initial repression, were tolerated by local authorities.[7] By the 1560s, the Protestant community had become a significant influence in the Netherlands, although it clearly formed a minority then.[8] In a society dependent on trade, freedom and tolerance were considered essential. Nevertheless, Charles V, and later Philip II, felt it was their duty to defeat Protestantism,[4] which was considered a heresy by the Catholic Church and a threat to the stability of the whole hierarchical political system. On the other hand, the intensely moralistic Dutch Protestants insisted their Biblical theology, sincere piety and humble lifestyle was morally superior to the luxurious habits and superficial religiosity of the ecclesiastical nobility.[9] The harsh measures led to increasing grievances in the Netherlands, where the local governments had embarked on a course of peaceful coexistence. In the second half of the century, the situation escalated. Philip sent troops to crush the rebellion and make the Netherlands once more a Catholic region. Although failing in his attempts to introduce the Spanish Inquisition directly, the Inquisition of the Netherlands was nevertheless sufficiently harsh and arbitrary in nature to provoke fervent dislike.[10]

Centralization

Part of the shifting balance of power in the late Middle Ages meant that besides the local nobility, many of the Dutch administrators by now were not traditional aristocrats, but instead stemmed from non-noble families that had risen in status over previous centuries. By the 15th century, Brussels had thus become the de facto capital of the Seventeen Provinces. Dating back to the Middle Ages the districts of the Netherlands, represented by its nobility and the wealthy city-dwelling merchants still had a large measure of autonomy in appointing its administrators. Charles V and Philip II set out to improve the management of the empire by increasing the authority of the central government in matters like law and taxes,[11] a policy which caused suspicion both among the nobility and the merchant class. An example of this is the takeover of power in the city of Utrecht in 1528 when Charles V supplanted the council of guild masters governing the city by his own stadtholder, who took over worldly powers in the whole province of Utrecht from the archbishop of Utrecht. Charles ordered the construction of the heavily fortified castle of Vredenburg, for defence against the Duchy of Gelre and to control the citizens of Utrecht.[12]

Under the governorship of Mary of Hungary (1531–1555), traditional power had for a large part been taken away both from the stadtholders of the provinces and from the high noblemen, who had been replaced by professional jurists in the Council of State.[13]

Initial stages (1555–1572)

Prelude to the rebellion (1555–1568)

In 1556 Charles passed on his throne to his son Philip II of Spain.[4] Charles, despite his harsh actions, had been seen as a ruler empathetic to the needs of the Netherlands. Philip, on the other hand, was raised in Spain and spoke neither Dutch nor French. During Philip's reign, tensions flared in the Netherlands over heavy taxation, suppression of Protestantism, and centralisation efforts. The growing conflict would reach a boiling point and lead ultimately to the war of independence.

Nobility in opposition

In an effort to build a stable and trustworthy government of the Netherlands, Philip appointed his half-sister Margaret of Parma as governor of the Netherlands.[4] He continued the policy of his father of appointing members of the high nobility of the Netherlands to the Raad van State (Council of State), the governing body of the seventeen Netherlands, that advised her. He made his confidant Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle head of that Council. However, already in 1558 the States of the provinces and the States-General of the Netherlands started to contradict Philip's wishes, by objecting to his tax proposals and by demanding, with eventual success, the withdrawal of Spanish troops which had been left by Philip to guard the Southern Netherlands' borders with France, but which they saw as a threat to their own independence (1559–1561).[15] Subsequent reforms met with much opposition, which was mainly directed at Granvelle. Petitions to King Philip by the high nobility went unanswered. Some of the most influential nobles, including Lamoral, Count of Egmont, Philip de Montmorency, Count of Hoorn, and William the Silent, withdrew from the Council of State until Philip recalled Granvelle.[4]

In late 1564, the nobles had noticed the growing power of the reformation and urged Philip to come up with realistic measures to prevent violence. Philip answered that sterner measures were the only answer. Subsequently Egmont, Horne and Orange withdrew once more from the Council, and Bergen and Meghem resigned their Stadholdership. During the same period, the religious protests were increasing in spite of increased oppression. In 1566, a league of about 400 members of the nobility presented a petition to the governor Margaret of Parma, to suspend persecution until the rest had returned. One of Margaret's courtiers, Count Berlaymont, called the presentation of this petition an act of "beggars" (French "gueux"), a name then taken up by the petitioners themselves (i.e. Geuzen). The petition was sent on to Philip for a final verdict.[4]

1566 — Iconoclasm and repression

The atmosphere in the Netherlands was tense due to the rebellion, preaching of Calvinist leaders, hunger after the bad harvest of 1565, and economic difficulties due to the Northern Seven Years' War. Early August 1566, a monastery church at Steenvoorde in Flanders (now in Northern France) was sacked by a mob led by the preacher Sebastian Matte.[17] This incident was followed by similar riots elsewhere in Flanders, and before long the Netherlands had become the scene of the Beeldenstorm, a riotous iconoclastic movement by Calvinists, who stormed churches and other religious buildings to desecrate and destroy church art and all kinds of decorative fittings over most of the country. The number of actual image-breakers appears to have been relatively small[18] and the exact backgrounds of the movement are debated,[19] but in general, local authorities did not step in to rein in the vandalism. The actions of the iconoclasts drove the nobility into two camps, with Orange and other grandees opposing the movement and others, notably Henry of Brederode, supporting it. Even before he answered the petition by the nobles, Philip had lost control in the troublesome Netherlands. He saw no other option than to send an army to suppress the rebellion. On 22 August 1567, Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba, marched into Brussels at the head of 10,000 troops.[20]

Alba took harsh measures and rapidly established a special court (Raad van Beroerten or Council of Troubles) to judge anyone who opposed the King. Alba considered himself the direct representative of Philip in the Netherlands and frequently bypassed Margaret of Parma and made use of her to lure back some of the fugitive nobles, notably the counts of Egmont and Horne, causing her to resign office in September 1567.[21] Egmont and Horne were arrested for high treason, condemned, and a year later decapitated on the Grand Place in Brussels. Egmont and Horne had been Catholic nobles, loyal to the King of Spain until their deaths. The reason for their execution was that Alba considered they had been treasonous to the king in their tolerance to Protestantism. Their executions, ordered by a Spanish noble, provoked outrage. More than one thousand people were executed in the following months.[3] The large number of executions led the court to be nicknamed the "Blood Court" in the Netherlands, and Alba to be called the "Iron Duke". Rather than pacifying the Netherlands, these measures helped to fuel the unrest.

William of Orange

William I of Orange was stadtholder of the provinces Holland, Zeeland and Utrecht, and Burgrave of Antwerp; and the most influential noble in the States General who had signed the petition. After the arrival of Alva, to avoid arrest, as had happened to Egmont and Horne, he fled to the lands ruled by his wife's father — the Count-Elector of Saxony. All his lands and titles in the Netherlands were forfeited to the Spanish King.

In 1568, William returned to try to drive the highly unpopular Duke of Alva from Brussels. William's nominal purpose was to remove misguided ministers like Alba, end rebellion, and thus restore the proper authority of King Phillip. This view is reflected in today's Dutch national anthem, the Wilhelmus, in which the last lines of the first stanza read: den koning van Hispanje heb ik altijd geëerd (I have always honoured the King of Spain). In pamphlets and in his letters to allies in the Netherlands William also called attention to the right of subjects to renounce their oaths of obedience if the sovereign would not respect their privileges.[22] William's forces moved into the Netherlands from four different directions. Armies led by his brothers invaded from Germany while French Huguenots invaded from the south. Although the Battle of Rheindalen near Roermond had occurred on 23 April 1568 and had been won by the Spanish, the Battle of Heiligerlee, fought on 23 May 1568, is commonly regarded as the beginning of the Eighty Years' War, and it was a victory for the rebel army. But the campaign ended in failure as William ran out of money and his own army disintegrated, while those of his allies were destroyed by the Duke of Alva. William remained at large and, as the only grandee still able to offer resistance, was from then on seen as the leader of the rebellion.

When the revolt broke out once more in 1572 he moved his court back to the Netherlands, to Delft in Holland, as the ancestral lands of Orange in Breda remained occupied by the Spanish. Delft remained William's base of operations until his assassination by Balthasar Gérard in 1584.

Resurgence (1572–1585)

.jpg)

Spain was hampered because it was waging war on multiple fronts simultaneously. Its struggle against the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean Sea put serious limits on the military power it could deploy against the rebels in the Netherlands. France too was opposing Spain at every juncture. Furthermore, England, particularly English privateers, were harassing Spanish shipping and its colonies in the Atlantic.

Already in 1566 William I of Orange had asked for Ottoman support. As Suleiman the Magnificent claimed that he felt religiously close to the Protestants, ("since they did not worship idols, believed in one God and fought against the Pope and Emperor")[23][24] he supported the Dutch together with the French and the English, as well as generally support Protestants and Calvinists,[23] as a way to counter Habsburg attempts at supremacy in Europe.[23]

Even so, by 1570 the Spanish had more or less suppressed the rebellion throughout the Netherlands. However, in March 1569, in an effort to finance his troops, Alba had proposed to the States that new taxes be introduced, among them the "Tenth Penny", a 1/10 levy on all sales other than landed property. This proposal was rejected by the States, and a compromise was subsequently agreed upon. Then, in 1571, Alba decided to press forward with the collection of the Tenth Penny regardless of the States' opposition.[25] This aroused strong protest from both Catholics and Protestants, and support for the rebels grew once more and was fanned by a large group of refugees who had fled the country during Alva's rule.

On 1 March 1572, the English Queen Elizabeth I ousted the Gueux, known as Sea Beggars, from the English harbours in an attempt to appease the Spanish King. The Gueux under their leader Lumey then unexpectedly captured the almost undefended town of Brill on 1 April. In securing Brill, the rebels had gained a foothold, and more importantly a token victory in the north. This was a sign for Protestants all over the Low Countries to rebel once more.[3]

Most of the important cities in the provinces of Holland and Zealand declared loyalty to the rebels. Notable exceptions were Amsterdam and Middelburg, which remained loyal to the Catholic cause until 1578. William of Orange was put at the head of the revolt. He was recognised as Governor-General and Stadholder of Holland, Zeeland, Friesland and Utrecht at a meeting in Dordrecht in July 1572. It was agreed that power would be shared between Orange and the States.[26] With the influence of the rebels rapidly growing in the northern provinces, the war entered a second and more decisive phase.

However, this also led to an increased discord amongst the Dutch. On one side there was a militant Calvinist minority that wanted to continue fighting the Catholic Philip II and convert all Dutch citizens to Calvinism. On the other end was a mostly Catholic minority that wanted to remain loyal to the governor and his administration in Brussels. In between was the large majority of (Catholic) Dutch that had no particular allegiance, but mostly wanted to restore Dutch privileges and the expulsion of the Spanish mercenary armies. William of Orange was the central figure who had to rally these groups to a common goal. In the end he was forced to move more and more towards the radical Calvinist side fighting the Spanish. He converted to Calvinism himself in 1573.[27]

Pacification of Ghent

Being unable to deal with the rebellion, Alba was replaced in 1573 by Luis de Requesens and a new policy of moderation was attempted. Spain, however, had to declare bankruptcy in 1575.

Don Luis de Requesens had not managed to broker a policy acceptable to both the Spanish King and the Netherlands when he died in early 1576.

The inability to pay the Spanish mercenary armies endured, leading to numerous mutinies and in November 1576 troops sacked Antwerp at the cost of some 8,000 lives. This so-called "Spanish Fury" strengthened the resolve of the rebels in the 17 provinces to take fate into their own hands.

The Netherlands negotiated an internal treaty, the Pacification of Ghent in the same year 1576, in which the provinces agreed to religious tolerance and pledged to fight together against the mutinous Spanish forces.

For the mostly Catholic provinces, the destruction by mutinous foreign troops was the principal reason to join in an open revolt, but formally the provinces still remained loyal to the sovereign Philip II.

However, some religious hostilities continued and Spain, aided by shipments of bullion from the New World, was able to send a new army under Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma and Piacenza.[3]

Unions of Arras and Utrecht

On 6 January 1579, prompted by the new Spanish governor Alexander Farnese, the later Duke of Parma, and upset by aggressive Calvinism, some of the Southern States (County of Artois, County of Hainaut and the so-called Walloon Flanders located in what is now France and Wallonia) left the alliance agreed upon by the pacification of Ghent and signed the Union of Arras (Atrecht), expressing their loyalty to the Spanish king. This meant an early end to the goal of united independence for the 17 provinces of the Low Countries on the basis of religious tolerance, agreed upon only three years previously.

In response to the union of Arras, William united the provinces of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders and Groningen in the Union of Utrecht on 23 January 1579; Brabant and Flanders joined a month later, in February 1579. Effectively, the 17 provinces were now divided into a southern group loyal to the Spanish king, and a rebellious northern group.

Act of Abjuration

In 16th century Europe, it was assumed that every country would have a king or other noble as head of state. Having repudiated Philip, States General tried to find a suitable replacement. The Protestant Queen of England, Elizabeth I, seemed the obvious choice to be protector of the Netherlands. Elizabeth, however, found the idea abhorrent. Her intervention for the French Huguenots (see the Treaty of Hampton Court) had been a costly mistake, and she had resolved never again to involve herself in any of her fellow monarchs’ domestic affairs. Not only would intervention provoke Philip, but it would set a dangerous precedent. If she could interfere in other monarchs' affairs, they could return the favour. (Elizabeth did later provide aid to the Dutch rebels in the Treaty of Nonsuch (1585), and as a consequence Philip aided Irish rebels in the Nine Years' War.)

The States-General then (in 1581) invited François, Duke of Anjou (younger brother of King Henry III of France), to be sovereign ruler. Anjou accepted on the condition that the Netherlands officially renounce any loyalty to Philip. In 1581, the States-General issued the Act of Abjuration, which declared that the King of Spain had not upheld his responsibilities to the people of the Netherlands and therefore would no longer be accepted as the rightful sovereign. Anjou arrived in February 1582. Though welcomed in some cities, he was rejected by Holland and Zeeland. Most of the people distrusted him as a Catholic, and the States-General granted him very limited powers. He brought a small French army to the Netherlands, and then decided to seize control of Antwerp by force in January 1583. This attempt failed disastrously, and Anjou left the Netherlands.

Elizabeth was now offered the sovereignty of the Netherlands, but she declined. All options for foreign royalty being exhausted, the States-General eventually decided to rule as a republican body instead.

The Fall of Antwerp

Immediately after the Act of Abjuration, Spain sent a new army to recapture the United Provinces. Over the following years, Parma reconquered the major part of Flanders and Brabant, as well as large parts of the northeastern provinces. The Roman Catholic religion was restored in much of this area. In 1585, Antwerp — the largest city in the Low Countries at the time — fell into his hands, which caused over half its population to flee to the north (see also Siege of Antwerp). Between 1560 and 1590, the population of Antwerp plummeted from c. 100,000 inhabitants to c. 42,000.[28]

William of Orange, who had been declared an outlaw by Philip II in March 1580,[29] was assassinated by a supporter of the King on 10 July 1584. He would be succeeded as leader of the rebellion by his son Maurice of Nassau, Prince of Orange.

The Netherlands were split into an independent northern part and a southern part which remained under Spanish control. Due to the almost uninterrupted rule of the Calvinist-dominated separatists, most of the population of the northern provinces became converted to Protestantism over the next decades. The south, under Spanish rule, remained a Catholic stronghold; most of its Protestants fled to the north. Spain retained a large military presence in the south, where it could also be used against France.

De facto independence of the north (1585–1609)

With the war going against them, the United Provinces had sought help from the kingdoms of France and England and, in February to May 1585, even offered each monarch sovereignty over the Netherlands, but both had declined.[30]

While England had unofficially been supporting the Dutch for years, Elizabeth had not officially supported the Dutch because she was afraid it might aggravate Spain into a war. However, the year before, the French Catholic League had signed a treaty with Spain to destroy the French Protestants. Afraid that France would fall under control of the Habsburgs, Elizabeth now decided to act. In 1585, under the Treaty of Nonsuch, Elizabeth I sent the Earl of Leicester to take the rule as lord-regent, with 5,000 to 6,000 troops, including 1,000 cavalry. The Earl of Leicester proved to be a poor commander, and also did not understand the sensitive trade arrangements between the Dutch regents and the Spanish. Moreover, Leicester sided with the radical Calvinists, earning him the distrust of the Catholics and moderates. Leicester also collided with many Dutch patricians when he tried to strengthen his own power at the cost of the Provincial States. Within a year of his arrival, he had lost his public support. Leicester returned to England, after which the States-General, being unable to find any other suitable regent, appointed Maurice of Orange (William's son), at the age of 20, to the position of Captain General of the Dutch army in 1587. On 7 September 1589 Philip II ordered Parma to move all available forces south to prevent Henry of Navarre from becoming King of France.[31] For Spain the Netherlands had become a side show in comparison to the French Wars of Religion.

The borders of the present-day Netherlands were largely defined by the campaigns of Maurice of Orange. The Dutch successes owed not only to his tactical skill but also to the financial burden Spain incurred replacing ships lost in the disastrous campaign of the Spanish Armada in 1588, and the need to refit its navy to recover control of the sea after the subsequent English counterattack. One of the most notable features of this war are the number of mutinies by the troops in the Spanish army because of arrears of pay. At least 40 mutinies in the period 1570 to 1607 are known.[32] In 1595, when Henry IV of France declared war against Spain, the Spanish government declared bankruptcy again. However, by regaining control of the sea, Spain was able to greatly increase its supply of gold and silver from the Americas, which allowed it to increase military pressure on England and France.

Under financial and military pressure, in 1598, Philip ceded the Netherlands to his favourite daughter Isabella and to her husband, Philip's nephew Archduke Albert of Austria (they proved to be highly competent governors) following the conclusion of the Treaty of Vervins with France. By that time Maurice was engaged in conquering important cities in the Netherlands. Starting with the important fortification of Bergen op Zoom (1588), Maurice conquered Breda (1590), Zutphen, Deventer, Delfzijl and Nijmegen (1591), Steenwijk, Coevorden (1592) Geertruidenberg (1593) Groningen (1594) Grol, Enschede, Ootmarsum, Oldenzaal (1597) and Grave (1602).[33] As this campaign was restricted to the border areas of the current Netherlands, the heartland of Holland remained at peace, during which time it moved into its Golden age.

By now, it had become clear that Spanish control of the Southern Netherlands was strong. However, control over Zeeland meant that the Northern Netherlands could control and close the estuary of the Scheldt, the entry to the sea for the important port of Antwerp. The port of Amsterdam benefited greatly from the blockade of the port of Antwerp, to the extent that merchants in the North began to question the desirability of reconquering the South. A campaign to control the Southern provinces' coast region was launched against Maurice's advice in 1600. Although portrayed as a liberation of the Southern Netherlands, the campaign was chiefly aimed at eliminating the threat to Dutch trade posed by the Spanish-supported Dunkirkers. The Spaniards strengthened their positions along the coast, leading to the Battle of Nieuwpoort.

Although the States-General army won great acclaim for itself and its commander by inflicting a then-surprising defeat of a Spanish army in open battle, Maurice halted the march on Dunkirk and returned to the Northern Provinces. Maurice never forgave the regents, led by van Oldenbarneveld, for being sent on this mission. By now the division of the Netherlands into separate states had become almost inevitable. With the failure to eliminate the Dunkirk threat to trade, the states decided to build up their navy to protect sea trade, which had greatly increased through the creation of the Dutch East Indies Company in 1602. The strengthened Dutch fleets would prove to be a formidable force, hampering Spain's naval ambitions thereafter.

Twelve Years' Truce (1609–1621)

1609 saw the start of a ceasefire, afterwards called the Twelve Years' Truce, between the United Provinces and the Spanish controlled southern states, mediated by France and England at The Hague. It was during this ceasefire the Dutch made great efforts to build their navy, which was later to have a crucial bearing on the course of the war.

During the Truce, two factions emerged in the Dutch camp, along political and religious lines. On one side were the Arminians, whose prominent supporters included Johan van Oldenbarnevelt and Hugo Grotius.[34] They tended to be well-to-do merchants who accepted a less strict interpretation of the Bible than did classical Calvinists. They were opposed by the more radical Gomarists, who had openly proclaimed their allegiance to Prince Maurice in 1610.[35] In 1617 the conflict escalated when republicans pushed the "Sharp Resolution", allowing the cities to take measures against the Gomarists. Prince Maurice accused van Oldenbarnevelt of treason, had him arrested, and in 1619, executed. Hugo Grotius fled the country after escaping from imprisonment in Castle Loevestein.[34]

Final stages (1621–1648)

War recommences

Negotiations for a permanent peace went on throughout the truce. Two major issues could not be resolved. First, the Spanish demand for religious freedom of Catholics in Northern Netherlands was countered by a Dutch demand for a similar religious freedom for Protestants in the Southern Netherlands. Second, there was a growing disagreement over the trade routes to the different colonies (in the Far East and the Americas) which could not be resolved. The Spanish made one last effort to reconquer the North, and the Dutch used their navy to enlarge their colonial trade routes to the detriment of Spain. The war was on once more — and crucially, merging with the wider Thirty Years' War.

In 1622, a Spanish attack on the important fortress town of Bergen op Zoom was repelled. However, in 1625 Maurice died while the Spanish laid siege to the city of Breda. Ignoring orders, the Spanish commander Ambrogio Spinola succeeded in conquering the city of Breda. The war was now more focused on trade, much of it in between the Dutch and the Dunkirkers, but also Dutch attacks on Spanish convoys, and above all the seizure of the undermanned Portuguese trading forts and ill defended territories. Maurice's half-brother Frederick Henry had succeeded his brother and taken command of the army. Frederick Henry conquered the pivotal fortified city of 's-Hertogenbosch in 1629. This town, largest in the northern part of Brabant, had been considered to be impregnable from attack. Its loss was a serious blow to the Spanish.[36]

In 1632, Frederick Henry captured Venlo, Roermond, and Maastricht during his famous "March along the Meuse" in a pincer move to prepare for the conquest of the major cities of Flanders. Attempts in the next years to attack Antwerp and Brussels failed, however. The Dutch were disappointed by the lack of support they received from the Flemish population. This was mainly because of the pillaging of Tienen and the new generation that had been raised in Flanders and Brabant, which had been thoroughly reconverted to Roman Catholicism and now distrusted the Calvinist Dutch even more than it loathed the Spanish occupants.

Colonial theatre

As more European countries began to build their empires, the war between the countries extended to colonies as well. Battles for profitable colonies were fought as far away as Macau, East Indies, Ceylon, Formosa (Taiwan), the Philippines, Brazil, and others. The most important of these conflicts would become known as the Dutch-Portuguese War. The Dutch carved out a trading empire all over the world, using their dominance at sea to great advantage. The Dutch East India Company was founded to administer all Dutch trade with the East, while the Dutch West India Company did the same for the West.

In the Western colonies, the Dutch States General mostly restricted itself to supporting privateering by their captains in the Caribbean to drain the Spanish coffers and fill their own. The most successful of these raids was the capture of the larger part of the Spanish treasure fleet by Piet Hein in 1628, which allowed Frederick Henry to finance the siege of 's Hertogenbosch, and seriously troubled Spanish payments of troops. But attempts were also made to conquer existing colonies or found new ones in Brazil, North America and Africa. Most of these would be only briefly or partially successful.[37] In the East the activities led to the conquest of many profitable trading colonies, a major factor in bringing about the Dutch Golden Age.[38]

From war to peace

In 1639, Spain sent an armada bound for Flanders, carrying 20,000 troops, to assist in a last large-scale attempt to defeat the northern rebels. The armada was decisively defeated by Lieutenant-Admiral Maarten Tromp in the Battle of the Downs. This victory had historic consequences far beyond the Eighty Years' War as it marked the end of Spain as the dominant sea power.

An alliance with France changed the balance of power. The Republic could now hope to reconquer the Southern Netherlands. However, this would not mean that they would become a part of the Netherlands, but that they would be divided among the victors, resulting in a powerful French state bordering the Republic. Furthermore, it would mean that the port of Antwerp would most likely no longer be blockaded and might become serious competition for Amsterdam. With the Thirty Years' War decided, there was also no longer any need to fight on to support fellow Protestant nations. As a result, the decision was made to end the war.[39]

Peace

On 30 January 1648, the war ended with the Treaty of Münster between Spain and the Netherlands. In Münster on 15 May 1648, the parties exchanged ratified copies of the treaty. This treaty was part of the European-scale Peace of Westphalia that also ended the Thirty Years' War. In the treaty, the power balance in Western Europe was readjusted to the actual geopolitical reality. This meant that de jure the Dutch Republic was recognised as an independent state and retained control over the territories that were conquered in the later stages of the war.[40] The new republic consisted of seven provinces: Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, Overijssel, Friesland, and Groningen. Each province was governed by its local Provincial States and by a stadtholder. In theory, each stadtholder was elected and subordinate to the States-General. However, the princes of Orange-Nassau, beginning with William I of Orange, became de facto hereditary stadtholders in Holland and Zeeland. In practice they usually became stadtholder of the other provinces as well. A constant power struggle, which already had shown its precursor during the Twelve years' Truce, emerged between the Orangists, who supported the stadtholders, and the Regent's supporters.

The border states, parts of Flanders, Brabant and Limburg that were conquered by the Dutch in the final stages of the war, were to be federally governed by the States-General. These were the so-called Generality Lands (Generaliteitslanden), which consisted of Staats-Brabant (present North Brabant), Staats-Vlaanderen (present Zeeuws-Vlaanderen) and Staats-Limburg (around Maastricht).

The peace would not be long-lived as the newly emerged world powers, the Republic of the Netherlands and the Commonwealth of England, would start their first war in 1652, only four years after the peace was signed.

Aftermath

Nature of the war

The Eighty Years' War began with a series of battles mostly fought by mercenaries, as was typical of the time. While successes for both parties were limited, costs were high and continued to grow as the war progressed. The structural inability of the Spanish government to pay its soldiers—it went bankrupt several times—led to perpetual large-scale mutinies among the Spanish army in the Netherlands, which continually frustrated Spain's military campaigns. On the Dutch side the States of Holland, with its opulent capital Amsterdam, bore the brunt of the costs of war and were able to do so successfully. The Spanish effort in the Netherlands was also hampered by the war against the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean during the 1570s, which demanded much of Spain's financial and human resources.

As the revolt and its suppression centred largely around issues of religious freedom and taxation, the conflict necessarily involved not only soldiers, but also civilians at all levels of society. This may be one reason for the resolve and subsequent successes of the Dutch rebels in defending cities. Another factor was the fact that the unpopularity of the Spanish army, which existed even before the start of the revolt,[41] was exacerbated when in the early stage of the war a few cities were purposely sacked by the Spanish troops after having surrendered; this was done to intimidate the remaining rebel cities into surrender. Given the involvement of all sectors of Dutch society in the conflict, a more-or-less organised, irregular army emerged alongside the regular forces. Among these were the geuzen (from the French word "gueux" meaning "beggars"), who waged a guerrilla war against Spanish interests. Especially at sea, the 'watergeuzen' were effective agents of the Dutch cause.

Another aspect of warfare in the Netherlands was its relatively static character. There were very few pitched battles where armies met in the field. Most military operations were sieges, as was typical of the era, resulting in protracted and expensive use of the military forces available. The Dutch had fortified most of their cities and even many smaller towns in accordance with the most modern views of the time, and these cities had to be subdued one by one. Sometimes sieges were broken off when the enemy threatened to attack the besieging army, or, on the Spanish side, conquered cities were given up immediately, or occasionally sold back to the Dutch, when the conquering army turned mutinous.

In the later stages, Maurice raised a professional standing army that was even paid when no hostilities were taking place, a radical innovation in that time and part of the Military Revolution.[42] This ensured him of loyal soldiers, who were trained in co-operating among each other and were intimately familiar with the doctrines of their commanders and were capable of carrying out complicated manoeuvres.

Effect on the Low Countries

In the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549, Charles V established the Seventeen Provinces of the Netherlands as an entity separate from France, Burgundy, or the Holy Roman Empire. The Netherlands at this point were among the wealthiest regions in Europe, and an important center of trade, finance, and art. The Eighty Years' War introduced a sharp breach in the region, with the Dutch Republic (the present-day Netherlands) growing into a world power (see Dutch Golden Age), and the Southern Netherlands (more or less present-day Belgium) losing much of its economic and cultural significance for centuries to come. The naval blockade during much of the Eighty Years' War of Antwerp, once the largest commercial centre of Europe, greatly contributed to the rise of Amsterdam as the new centre of European and world trade.

Politically, a unique situation had emerged in the Netherlands where a republican body (the States General) ruled, but where a (increasingly hereditary) noble function of Stadtholder was occupied by the house of Orange-Nassau. This division of power prevented large scale fighting between nobility and civilians as happened in the English Civil War. The frictions between the civil and noble fractions, that already started in the twelve years' truce, were numerous and would finally lead to an outburst with the French supported Batavian Republic, where Dutch bourgeoisie hoped to get rid of the increasing self-esteem in the nobility once and for all. However, in a dramatic resurgence of nobility after the Napoleonic era the republic would be abandoned in favour of the foundation of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. Thus, one of the oldest republics of Europe was turned into a monarchy, which it still is today.

Effect on the Spanish Empire

The conquest of various American territories made Spain the leading European power of the 16th century. This brought them into continuous conflict with France and the emerging power that was England. In addition, the deeply religious monarchs Charles V and Philip II saw a role for themselves as protectors of the Catholic faith against Islam in the Mediterranean and against Protestantism in northern Europe. This meant the Spanish Empire was almost continuously at war. Of all these conflicts, the Eighty Years' War was the most prolonged and had a major effect on the Spanish finances and the morale of the Spanish people, who saw taxes increase and soldiers not returning, with little successes to balance the scales. The Spanish government had to declare several bankruptcies. The Spanish population increasingly questioned the necessity of the war in the Netherlands. The loss of Portugal in 1640 and the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, ending the war were the first signs that the role of the Spanish Empire in Europe was declining.

Political implications in Europe

The Dutch revolt against their lawful sovereign, most obviously illustrated in the Act of abjuration (1581), implied that a sovereign could be deposed by the population if there was agreement that he did not fulfill his God given responsibility. This act by the Dutch challenged the concept of a divine right of kings, and eventually led to the Dutch Republic. The acceptance of a non-monarchic country by the other European powers in 1648 spread across Europe, fuelling resistance against the divine power of Kings.

See also

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the Netherlands |

|

| Netherlands portal |

- Battles of the Eighty Years' War

- Dutch-Portuguese War

- Eighty Years' War

- European wars of religion

- Synod of Dordrecht

- Union of Delft

Notes

- ↑ This article adopts 1568 as the starting date of the war, as this was the year of the first battles between armies. However, since there is a long period of Protestant vs. Catholic (establishment) unrest leading to this war, it is not easy to give an exact date when the war started. The first open violence that would lead to the war was the 1566 iconoclasm, and sometimes the first Spanish repressions of the riots (i.e. battle of Oosterweel, 1567) are considered the starting point. Most accounts cite the 1568 invasions of armies of mercenaries paid by William of Orange as the official start of the war; this article adopts that point of view. Alternatively, the start of the war is sometimes set at the capture of Brielle by the Gueux in 1572.

References

- ↑ Knutsen, Torbjørn L. (1999). The Rise and Fall of World Orders. Manchester University Press. p. 29. ISBN 0719040582.

- ↑ Huizinga, Johan (1997). The Autumn of the Middle Ages (Dutch edition—Herfsttij der Middeleeuwen) (26th (1st—1919) ed.). Olympus. ISBN 90-254-1207-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Kamen, Henry (2005). Spain, 1469–1714: a society of conflict (3rd ed.). Harlow, United Kingdom: Pearson Education. ISBN 0-582-78464-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Geyl, Pieter (2001). History of the Dutch-Speaking peoples 1555–1648 (1sr (combines two volumes from 1932 and 1936) ed.). Phoenix Press, London UK. ISBN 1-84212-225-8.

- ↑ Jansen, H. P. H. (2002). Geschiedenis van de Middeleeuwen (in Dutch) (12th (1st—1978) ed.). Het Spectrum. ISBN 90-274-5377-2.

- ↑ Israel, J. I. (1998). The Dutch Republic Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806 (1st paperback (1st—1995) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 132–134. ISBN 0-19-820734-4.

- ↑ Israel, J. I. (1998). The Dutch Republic Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806 (1st paperback (1st—1995) ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-19-820734-4.

- ↑ R. Po-chia Hsia, ed. A Companion to the Reformation World (2006) pp 118–34

- ↑ R. Po-chia Hsia, ed. A Companion to the Reformation World (2006) pp 3–36

- ↑ Israel, J. I. (1998). The Dutch Republic Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806 (1st paperback (1st—1995) ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 155. ISBN 0-19-820734-4.

- ↑ Israel, J. I. (1998). The Dutch Republic Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806 (1st paperback (1st—1995) ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 127. ISBN 0-19-820734-4.

- ↑ de Bruin, R. E.; T. J. Hoekstra; A. Pietersma (1999). The city of Utrecht through twenty centuries : a brief history (1st ed.). SPOU and the Utrecht Archief; Utrecht Nl. ISBN 90-5479-040-7.

- ↑ Van Nierop, H., "Alva's Throne—making sense of the revolt of the Netherlands". In: Darby, G. (ed), The Origins and Development of the Dutch Revolt (Londen/New York 2001) pp. 29–47, 37

- ↑ Motley, John Lothrop (1885). The Rise of the Dutch Republic. vol. I. Harper Brothers.

As Philip was proceeding on board the ship which was to bear him forever from the Netherlands, his eyes lighted upon the Prince. His displeasure could no longer be restrained. With angry face he turned upon him, and bitterly reproached him for having thwarted all his plans by means of his secret intrigues. William replied with humility that every thing which had taken place had been done through the regular and natural movements of the states. Upon this the King, boiling with rage, seized the Prince by the wrist, and shaking it violently, exclaimed in Spanish, "No los estados, ma vos, vos, vos!—Not the estates, but you, you, you!" repeating thrice the word vos, which is as disrespectful and uncourteous in Spanish as "toi" in French.

- ↑ G. Parker, The Dutch Revolt. Revised edition (1985), 46.

- ↑ "The birth and growth of Utrecht"

- ↑ G. Parker, The Dutch Revolt. Revised edition (1985), pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Limm (1989) notes that "there were few cases of more than 200 people being involved at any one time", even in the northern provinces, where large crowds often attended the iconoclasm (p. 25). In the case of the southern provinces, he speaks of a relatively small, orderly group moving along the country.

- ↑ See Spaans (1999), 152 ff., where she argues that iconoclasm was actually organized by local elites for political reasons (Spaans, J. "Catholicism and Resistance to the Reformation in the Northern Netherlands". In: Benedict, Ph., and others (eds), Reformation, Revolt and Civil War in France and the Netherlands, 1555–1585 (Amsterdam 1999), pp. 149–163).

- ↑ Van der Horst, Han (2000). Nederland, de vaderlandse geschiedenis van de prehistorie tot nu (in Dutch) (3rd ed.). Bert Bakker. ISBN 90-351-2722-6.

- ↑ Limm, Peter (1989). The Dutch Revolt, 1559–1648 (1st ed.). London, UK: Longman. p. 30.

- ↑ Limm 1989, p. 32.

- 1 2 3 The Ottoman state and its place in world history by Kemal H. Karpat p.53

- ↑ Muslims and the Gospel by Roland E. Miller p.208

- ↑ Limm 1989, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Limm 1989, p. 40

- ↑ Limm 1989, p. 40.

- ↑ Marnef, G. "The towns and the revolt". In: Darby, G. (ed), The Origins and Development of the Dutch Revolt (Londen/New York 2001) 84–106; 85 and 103.

- ↑ Limm 1989, pp. 53 and 55.

- ↑ Israel (1998), 219

- ↑ G.Parker 1972; 245 The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road 1567–1659 Cambridge University Press

- ↑ listed in Appendix J in G.Parker 1972 The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road 1567–1659 Cambridge University Press

- ↑ Blokker, Jan (2006). Waar is de Tachtigjarige Oorlog gebleven? (in Dutch) (1st ed.). De Harmonie. ISBN 90-6169-741-7.

- 1 2 Motley, John L. (1874). The Life and Death of John of Barneveld. Project Gutenberg.

- ↑ Israel, J. I. (1998). The Dutch Republic Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806 (1st paperback (1st—1995) ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 431. ISBN 0-19-820734-4.

- ↑ According to Israel (1998, 507–508), the fall of 's-Hertogenbosch represented "a shattering blow to Spanish prestige" and was 'epoch-making' for the fact that, for the first time in the war, the Dutch appeared to enjoy overall strategic superiority. The event caused Philip IV to overrule his ministers and offer an unconditional truce, which was rejected (Israel 1998, 508).

- ↑ Heijer, den, Henk J. (2002). De geschiedenis van de West-Indische Compagnie (2nd ed.). Zutphen, Netherlands: Walburg Pers. ISBN 90-6011-912-6.

- ↑ Gaastra, Femme S. (1991). De geschiedenis van de VOC (2nd ed.). Zutphen, Netherlands: Walburg Pers. ISBN 90-6011-929-0.

- ↑ Blom, J.C.H. (1993). Geschiedenis van de Nederlanden (2nd ed.). Rijswijk, Netherlands: Nijgh en Van Ditmar Universitair. ISBN 90-237-1164-5.

- ↑ Osiander, Andreas (Spring 2001). "Sovereignty, International Relations, and the Westphalian Myth". International Organization 55 (2): 251–287. doi:10.1162/00208180151140577.

- ↑ Parker (1985, 46) cites Granvelle commenting that "people here universally display discontent with any and all Spaniards in these provinces" in a letter to Philip II of 10 March 1563, and refers to Margaret of Parma's objections to Alva's intention of billeting his "unpopular tercios" on loyal Flemish towns at his arrival in August 1568 (Parker 1985, 104).

- ↑ This is argued by M. Roberts in "The Military Revolution, 1560–1660" (inaugural lecture, Belfast 1955).

Further reading

- The works of John Lothrop Motley (1814–1877) give an old but very detailed account of the Dutch republic in this time; Motley chamioned the Protestant cause—Works by John Lothrop Motley at Project Gutenberg (free E-texts)

- Geyl, Pieter. (1932), The Revolt of the Netherlands, 1555–1609. Williams & Norgate, UK.

- Geyl, Pieter. (1936), The Netherlands Divided, 1609–1648. Williams & Norgate, UK.

- Israel, Jonathan I. (1998), The Dutch Republic. Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806, Clarendon Press, Oxford, ISBN 0-19-820734-4.

- Koenigsberger, H.G. (2007) [2001] Monarchies, States Generals and Parliaments. The Netherlands in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Cambridge U.P., ISBN 978-0-521-04437-0 paperback

- Parker, Geoffrey (1977), The Dutch revolt, Penguin books, London

- Pepijn Brandon (2007), "The Dutch Revolt: a Social Analysis" from International Socialism journal 116, autumn 2007.

- Rodríguez Pérez, Yolanda, The Dutch Revolt through Spanish Eyes: Self and Other in historical and literary texts of Golden Age Spain (c. 1548–1673) (Oxford etc., Peter Lang, 2008) (Hispanic Studies: Culture and Ideas, 16).

Historiography

- Marnef, Guido. "Belgian and Dutch Post-war Historiography on the Protestant and Catholic Reformation in the Netherlands," Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte (2009) Vol. 100, pp 271–292.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eighty Years' War. |

- De Bello Belgico – about the Revolt of the Netherlands, website of Leiden University, also in English

- De canon van Nederland – about Dutch history, contains topics related to the Eighty Years' War, also in English

- (Spanish) Las guerras de Flandes – about the Flanders' War