Skewness

In probability theory and statistics, skewness is a measure of the asymmetry of the probability distribution of a real-valued random variable about its mean. The skewness value can be positive or negative, or even undefined.

The qualitative interpretation of the skew is complicated. For a unimodal distribution, negative skew indicates that the tail on the left side of the probability density function is longer or fatter than the right side – it does not distinguish these shapes. Conversely, positive skew indicates that the tail on the right side is longer or fatter than the left side. In cases where one tail is long but the other tail is fat, skewness does not obey a simple rule. For example, a zero value indicates that the tails on both sides of the mean balance out, which is the case for a symmetric distribution, but is also true for an asymmetric distribution where the asymmetries even out, such as one tail being long but thin, and the other being short but fat. Further, in multimodal distributions and discrete distributions, skewness is also difficult to interpret. Importantly, the skewness does not determine the relationship of mean and median.

Introduction

Consider the two distributions in the figure just below. Within each graph, the bars on the right side of the distribution taper differently than the bars on the left side. These tapering sides are called tails, and they provide a visual means for determining which of the two kinds of skewness a distribution has:

- negative skew: The left tail is longer; the mass of the distribution is concentrated on the right of the figure. The distribution is said to be left-skewed, left-tailed, or skewed to the left.[1]

- positive skew: The right tail is longer; the mass of the distribution is concentrated on the left of the figure. The distribution is said to be right-skewed, right-tailed, or skewed to the right.[1]

.svg.png)

Skewness in a data series may be observed not only graphically but by simple inspection of the values. For instance, consider the numeric sequence (49, 50, 51), whose values are evenly distributed around a central value of (50). We can transform this sequence into a negatively skewed distribution by adding a value far below the mean, as in e.g. (40, 49, 50, 51). Similarly, we can make the sequence positively skewed by adding a value far above the mean, as in e.g. (49, 50, 51, 60).

Relationship of mean and median

The skewness is not strictly connected with the relationship between the mean and median: a distribution with negative skew can have the mean greater than or less than the median, and likewise for positive skew.

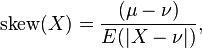

In the older notion of nonparametric skew, defined as  where µ is the mean, ν is the median, and σ is the standard deviation, the skewness is defined in terms of this relationship: positive/right nonparametric skew means the mean is greater than (to the right of) the median, while negative/left nonparametric skew means the mean is less than (to the left of) the median. However, the modern definition of skewness and the traditional nonparametric definition do not in general have the same sign: while they agree for some families of distributions, they differ in general, and conflating them is misleading.

where µ is the mean, ν is the median, and σ is the standard deviation, the skewness is defined in terms of this relationship: positive/right nonparametric skew means the mean is greater than (to the right of) the median, while negative/left nonparametric skew means the mean is less than (to the left of) the median. However, the modern definition of skewness and the traditional nonparametric definition do not in general have the same sign: while they agree for some families of distributions, they differ in general, and conflating them is misleading.

If the distribution is symmetric, then the mean is equal to the median, and the distribution has zero skewness.[2] If, in addition, the distribution is unimodal, then the mean = median = mode. This is the case of a coin toss or the series 1,2,3,4,... Note, however, that the converse is not true in general, i.e. zero skewness does not imply that the mean is equal to the median.

Paul T. von Hippel points out: "Many textbooks, teach a rule of thumb stating that the mean is right of the median under right skew, and left of the median under left skew. This rule fails with surprising frequency. It can fail in multimodal distributions, or in distributions where one tail is long but the other is heavy. Most commonly, though, the rule fails in discrete distributions where the areas to the left and right of the median are not equal. Such distributions not only contradict the textbook relationship between mean, median, and skew, they also contradict the textbook interpretation of the median."[3]

Definition

Pearson's moment coefficient of skewness

The skewness of a random variable X is the moment coefficient of skewness.[4] It is sometimes referred to as Pearson's moment coefficient of skewness,[5] not to be confused with Pearson's other skewness statistics (see below). It is the third standardized moment.[5][4] It is denoted γ1 and defined as

where μ3 is the third central moment, μ is the mean, σ is the standard deviation, and E is the expectation operator. The last equality expresses skewness in terms of the ratio of the third cumulant κ3 and the 1.5th power of the second cumulant κ2. This is analogous to the definition of kurtosis as the fourth cumulant normalized by the square of the second cumulant.

The skewness is also sometimes denoted Skew[X].

The formula expressing skewness in terms of the non-central moment E[X3] can be expressed by expanding the previous formula,

Examples

Skewness can be infinite, as when

or undefined, as when

In this latter example, the third cumulant is undefined. One can also have distributions such as

where both the second and third cumulants are infinite, so the skewness is again undefined.

Properties

Starting from a standard cumulant expansion around a normal distribution, one can show that

- skewness = 6 (mean − median) / standard deviation (1 + kurtosis / 8) + O(skewness2).

If Y is the sum of n independent and identically distributed random variables, all with the distribution of X, then the third cumulant of Y is n times that of X and the second cumulant of Y is n times that of X, so ![\mbox{Skew}[Y] = \mbox{Skew}[X]/\sqrt{n}](../I/m/d937ed361411562bcc2311fbcfe34588.png) . This shows that the skewness of the sum is smaller, as it approaches a Gaussian distribution in accordance with the central limit theorem. Note that the assumption that the variables be independent for the above formula is very important because it is possible even for the sum of two Gaussian variables to have a skewed distribution (see this example).

. This shows that the skewness of the sum is smaller, as it approaches a Gaussian distribution in accordance with the central limit theorem. Note that the assumption that the variables be independent for the above formula is very important because it is possible even for the sum of two Gaussian variables to have a skewed distribution (see this example).

Sample skewness

For a sample of n values, a natural method of moments estimator of the population skewness is[6]

where  is the sample mean, s is the sample standard deviation, and the numerator m3 is the sample third central moment.

is the sample mean, s is the sample standard deviation, and the numerator m3 is the sample third central moment.

Another common definition of the sample skewness is[6]

where  is the unique symmetric unbiased estimator of the third cumulant and

is the unique symmetric unbiased estimator of the third cumulant and  is the symmetric unbiased estimator of the second cumulant (i.e. the variance).

is the symmetric unbiased estimator of the second cumulant (i.e. the variance).

In general, the ratios  and

and  are both biased estimators of the population skewness

are both biased estimators of the population skewness  ; their expected values can even have the opposite sign from the true skewness. (For instance, a mixed distribution consisting of very thin Gaussians centred at −99, 0.5, and 2 with weights 0.01, 0.66, and 0.33 has a skewness of about −9.77, but in a sample of 3,

; their expected values can even have the opposite sign from the true skewness. (For instance, a mixed distribution consisting of very thin Gaussians centred at −99, 0.5, and 2 with weights 0.01, 0.66, and 0.33 has a skewness of about −9.77, but in a sample of 3,  has an expected value of about 0.32, since usually all three samples are in the positive-valued part of the distribution, which is skewed the other way.) Nevertheless,

has an expected value of about 0.32, since usually all three samples are in the positive-valued part of the distribution, which is skewed the other way.) Nevertheless,  and

and  each have obviously the correct expected value of zero for any symmetric distribution with a finite third moment, including a normal distribution.

each have obviously the correct expected value of zero for any symmetric distribution with a finite third moment, including a normal distribution.

The variance of the skewness of a random sample of size n from a normal distribution is[7][8]

An approximate alternative is 6/n, but this is inaccurate for small samples.

In normal samples,  has the smaller variance of the two estimators, with

has the smaller variance of the two estimators, with

where m2 in the denominator is the (biased) sample second central moment.[6]

The adjusted Fisher–Pearson standardized moment coefficient  is the version found in Excel and several statistical packages including Minitab, SAS and SPSS.[9]

is the version found in Excel and several statistical packages including Minitab, SAS and SPSS.[9]

Applications

Skewness has benefits in many areas. Many models assume normal distribution; i.e., data are symmetric about the mean. The normal distribution has a skewness of zero. But in reality, data points may not be perfectly symmetric. So, an understanding of the skewness of the dataset indicates whether deviations from the mean are going to be positive or negative.

D'Agostino's K-squared test is a goodness-of-fit normality test based on sample skewness and sample kurtosis.

Other measures of skewness

Other measures of skewness have been used, including simpler calculations suggested by Karl Pearson[10] (not to be confused with Pearson's moment coefficient of skewness, see above). These other measures are:

Pearson's first skewness coefficient (mode skewness)

The Pearson mode skewness,[11] or first skewness coefficient, is defined as

- (mean − mode) / standard deviation.

Pearson's second skewness coefficient (median skewness)

The Pearson median skewness, or second skewness coefficient,[12] is defined as

- 3 (mean − median) / standard deviation.

The latter is a simple multiple of the nonparametric skew.

Quantile-based measures

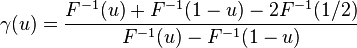

A skewness function

can be defined,[13][14] where F is the cumulative distribution function. This leads to a corresponding overall measure of skewness[13] defined as the supremum of this over the range 1/2 ≤ u < 1. Another measure can be obtained by integrating the numerator and denominator of this expression.[15] The function γ(u) satisfies −1 ≤ γ(u) ≤ 1 and is well defined without requiring the existence of any moments of the distribution.[15]

Galton's measure of skewness[16] is γ(u) evaluated at u = 3/4. Other names for this quantity are the Bowley skewness,[17] the Yule–Kendall index[18] and the quartile skewness.

Kelley's measure of skewness uses u = 0.1.

L-moments

Use of L-moments in place of moments provides a measure of skewness known as the L-skewness.[19]

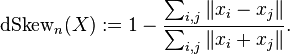

Distance skewness

A value of skewness equal to zero does not imply that the probability distribution is symmetric. Thus there is a need for another measure of asymmetry that has this property: such a measure was introduced in 2000.[20] It is called distance skewness and denoted by dSkew. If X is a random variable taking values in the d-dimensional Euclidean space, X has finite expectation, X' is an independent identically distributed copy of X, and  denotes the norm in the Euclidean space, then a simple measure of asymmetry is

denotes the norm in the Euclidean space, then a simple measure of asymmetry is

and dSkew(X) := 0 for X = 0 (with probability 1). Distance skewness is always between 0 and 1, equals 0 if and only if X is diagonally symmetric (X and −X have the same probability distribution) and equals 1 if and only if X is a nonzero constant with probability one.[21] Thus there is a simple consistent statistical test of diagonal symmetry based on the sample distance skewness:

Groeneveld & Meeden’s coefficient

Groeneveld & Meeden have suggested, as an alternative measure of skewness,[15]

where μ is the mean, ν is the median, |…| is the absolute value, and E() is the expectation operator.

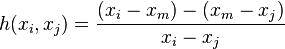

Medcouple

The medcouple is a scale-invariant robust measure of skewness, with a breakdown point of 25%. It is the median of the values of the kernel function

taken over all couples  such that

such that  , where

, where  is the median of the sample

is the median of the sample  .

.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Skewness (statistics). |

Notes

- 1 2 Susan Dean, Barbara Illowsky "Descriptive Statistics: Skewness and the Mean, Median, and Mode", Connexions website

- ↑ "1.3.5.11. Measures of Skewness and Kurtosis". NIST. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ↑ von Hippel, Paul T. (2005). "Mean, Median, and Skew: Correcting a Textbook Rule". Journal of Statistics Education 13 (2).

- 1 2 "Measures of Shape: Skewness and Kurtosis", 2008–2014 by Stan Brown, Oak Road Systems

- 1 2 Pearson's moment coefficient of skewness, FXSolver.com

- 1 2 3 Joanes, D. N.; Gill, C. A. (1998). "Comparing measures of sample skewness and kurtosis". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society (Series D): The Statistician 47 (1): 183–189. doi:10.1111/1467-9884.00122.

- ↑ Duncan Cramer (1997) Fundamental Statistics for Social Research. Routledge. ISBN 9780415172042 (p 85)

- ↑ Kendall, M.G.; Stuart, A. (1969) The Advanced Theory of Statistics, Volume 1: Distribution Theory, 3rd Edition, Griffin. ISBN 0-85264-141-9 (Ex 12.9)

- ↑ Doane DP, Seward LE (2011) J Stat Educ 19 (2)

- ↑ http://www.stat.upd.edu.ph/s114%20cnotes%20fcapistrano/Chapter%2010.pdf

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "Pearson Mode Skewness", MathWorld.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "Pearson's skewness coefficients", MathWorld.

- 1 2 MacGillivray (1992)

- ↑ Hinkley DV (1975) "On power transformations to symmetry", Biometrika, 62, 101–111

- 1 2 3 Groeneveld, R.A.; Meeden, G. (1984). "Measuring Skewness and Kurtosis". The Statistician 33 (4): 391–399. doi:10.2307/2987742. JSTOR 2987742.

- ↑ Johnson et al (1994) p 3, p 40

- ↑ Kenney JF and Keeping ES (1962) Mathematics of Statistics, Pt. 1, 3rd ed., Van Nostrand, (page 102)

- ↑ Wilks DS (1995) Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences, p 27. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-751965-3

- ↑ Hosking, J.R.M. (1992). "Moments or L moments? An example comparing two measures of distributional shape". The American Statistician 46 (3): 186–189. doi:10.2307/2685210. JSTOR 2685210.

- ↑ Szekely, G.J. (2000). "Pre-limit and post-limit theorems for statistics", In: Statistics for the 21st Century (eds. C. R. Rao and G. J. Szekely), Dekker, New York, pp. 411–422.

- ↑ Szekely, G. J. and Mori, T. F. (2001) "A characteristic measure of asymmetry and its application for testing diagonal symmetry", Communications in Statistics – Theory and Methods 30/8&9, 1633–1639.

References

- Johnson, NL, Kotz, S, Balakrishnan N (1994) Continuous Univariate Distributions, Vol 1, 2nd Edition Wiley ISBN 0-471-58495-9

- MacGillivray, HL (1992). "Shape properties of the g- and h- and Johnson families". Comm. Statistics — Theory and Methods 21: 1244–1250.

External links

| Wikiversity has learning materials about Skewness |

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Asymmetry coefficient", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- An Asymmetry Coefficient for Multivariate Distributions by Michel Petitjean

- On More Robust Estimation of Skewness and Kurtosis Comparison of skew estimators by Kim and White.

- Closed-skew Distributions — Simulation, Inversion and Parameter Estimation

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![\gamma_1 = \operatorname{E}\left[\left(\frac{X-\mu}{\sigma}\right)^3 \right]

= \frac{\mu_3}{\sigma^3}

= \frac{\operatorname{E}\left[(X-\mu)^3\right]}{\ \ \ ( \operatorname{E}\left[ (X-\mu)^2 \right] )^{3/2}}

= \frac{\kappa_3}{\kappa_2^{3/2}},](../I/m/6e3ce751b1c6d06c7c3fba42d257f1ea.png)

![\begin{align}

\gamma_1

&= \operatorname{E}\left[\left(\frac{X-\mu}{\sigma}\right)^3 \right] \\

& = \frac{\operatorname{E}[X^3] - 3\mu\operatorname E[X^2] + 3\mu^2\operatorname E[X] - \mu^3}{\sigma^3}\\

&= \frac{\operatorname{E}[X^3] - 3\mu(\operatorname E[X^2] -\mu\operatorname E[X]) - \mu^3}{\sigma^3}\\

&= \frac{\operatorname{E}[X^3] - 3\mu\sigma^2 - \mu^3}{\sigma^3}.

\end{align}](../I/m/d2a2f0cb60e6f9503e1300505f593b6b.png)

![\Pr \left[ X > x \right]=x^{-3}\mbox{ for }x>1,\ \Pr[X<1]=0](../I/m/b1212299616f2d94b3477c0373d30a78.png)

![\Pr[X<x]=(1-x)^{-3}/2\mbox{ for negative }x\mbox{ and }\Pr[X>x]=(1+x)^{-3}/2\mbox{ for positive }x.](../I/m/e3453c02fbbcb3296133c66db19bdece.png)

![\Pr \left[ X > x \right]=x^{-2}\mbox{ for }x>1,\ \Pr[X<1]=0,](../I/m/7c52d6b5f983b46b5f71a14c38a6da64.png)

![b_1 = \frac{m_3}{s^3}

= \frac{\tfrac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i-\overline{x})^3}{\left[\tfrac{1}{n-1} \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i-\overline{x})^2\right]^{3/2}}\ ,](../I/m/6c8549e691a2d0e15518a7677fa3cec6.png)