Interest rate

| Finance |

|---|

|

An interest rate is the rate at which interest is paid by borrowers (debtors) for the use of money that they borrow from lenders (creditors). Specifically, the interest rate is a percentage of principal paid a certain number of times per period for all periods during the total term of the loan or credit. Interest rates are normally expressed as a percentage of the principal for a period of one year, sometimes they are expressed for different periods such as a month or a day. Different interest rates exist parallelly for the same or comparable time periods, depending on the default probability of the borrower, the residual term, the payback currency, and many more determinants of a loan or credit. For example, a company borrows capital from a bank to buy new assets for its business, and in return the lender receives rights on the new assets as collateral and interest at a predetermined interest rate for deferring the use of funds and instead lending it to the borrower.

Interest-rate targets are a vital tool of monetary policy and are taken into account when dealing with variables like investment, inflation, and unemployment. The central banks of countries generally tend to reduce interest rates when they wish to increase investment and consumption in the country's economy. However, a low interest rate as a macro-economic policy can be risky and may lead to the creation of an economic bubble, in which large amounts of investments are poured into the real-estate market and stock market. In developed economies, interest-rate adjustments are thus made to keep inflation within a target range for the health of economic activities or cap the interest rate concurrently with economic growth to safeguard economic momentum.[1][2][3][4][5]

Interest rate notations

What is commonly referred to as the interest rate in the media is generally the rate offered on overnight deposits by the Central Bank or other authority, annualized.

The total interest on a loan or investment depends on the timescale the interest is calculated on, because interest paid may be compounded.

In retail finance, the annual percentage rate and effective annual rate concepts have been introduced to help consumers easily compare different products with different payment structures.

In business and investment finance, the effective interest rate is often derived from the yield, a composite measure which takes into account all payments of interest and capital from the investment. The notion of annual effective discount rate, often called simply the discount rate, is also used in finance, as an alternative measure to the effective annual rate which is more useful or standard in some contexts. A positive annual effective discount rate is always a lower number than the interest rate it represents.

Historical interest rates

In the past two centuries, interest rates have been variously set either by national governments or central banks. For example, the Federal Reserve federal funds rate in the United States has varied between about 0.25% to 19% from 1954 to 2008, while the Bank of England base rate varied between 0.5% and 15% from 1989 to 2009,[6][7] and Germany experienced rates close to 90% in the 1920s down to about 2% in the 2000s.[8][9] During an attempt to tackle spiraling hyperinflation in 2007, the Central Bank of Zimbabwe increased interest rates for borrowing to 800%.[10]

The interest rates on prime credits in the late 1970s and early 1980s were far higher than had been recorded – higher than previous US peaks since 1800, than British peaks since 1700, or than Dutch peaks since 1600; "since modern capital markets came into existence, there have never been such high long-term rates" as in this period.[11]

Possibly before modern capital markets, there have been some accounts that savings deposits could achieve an annual return of at least 25% and up to as high as 50%. (William Ellis and Richard Dawes, "Lessons on the Phenomenon of Industrial Life... ", 1857, p III–IV)

Reasons for interest rate changes

- Political short-term gain: Lowering interest rates can give the economy a short-run boost. Under normal conditions, most economists think a cut in interest rates will only give a short term gain in economic activity that will soon be offset by inflation. The quick boost can influence elections. Most economists advocate independent central banks to limit the influence of politics on interest rates.

- Deferred consumption: When money is loaned the lender delays spending the money on consumption goods. Since according to time preference theory people prefer goods now to goods later, in a free market there will be a positive interest rate.

- Inflationary expectations: Most economies generally exhibit inflation, meaning a given amount of money buys fewer goods in the future than it will now. The borrower needs to compensate the lender for this.

- Alternative investments: The lender has a choice between using his money in different investments. If he chooses one, he forgoes the returns from all the others. Different investments effectively compete for funds.

- Risks of investment: There is always a risk that the borrower will go bankrupt, abscond, die, or otherwise default on the loan. This means that a lender generally charges a risk premium to ensure that, across his investments, he is compensated for those that fail.

- Liquidity preference: People prefer to have their resources available in a form that can immediately be exchanged, rather than a form that takes time to realize.

- Taxes: Because some of the gains from interest may be subject to taxes, the lender may insist on a higher rate to make up for this loss.

- Banks: Banks can tend to change the interest rate to either slow down or speed up economy growth. This involves either raising interest rates to slow the economy down, or lowering interest rates to promote economic growth.[12]

- Economy: Interest rates can fluctuate according to the status of the economy. It will generally be found that if the economy is strong then the interest rates will be high, if the economy is weak the interest rates will be low.

Real vs nominal interest rates

The nominal interest rate is the amount, in percentage terms, of interest payable.

For example, suppose a household deposits $100 with a bank for 1 year and they receive interest of $10. At the end of the year their balance is $110. In this case, the nominal interest rate is 10% per annum.

The real interest rate, which measures the purchasing power of interest receipts, is calculated by adjusting the nominal rate charged to take inflation into account. (See real vs. nominal in economics.)

If inflation in the economy has been 10% in the year, then the $110 in the account at the end of the year buys the same amount as the $100 did a year ago. The real interest rate, in this case, is zero.

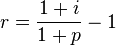

After the fact, the 'realized' real interest rate, which has actually occurred, is given by the Fisher equation, and is

where p = the actual inflation rate over the year. The linear approximation

is widely used.

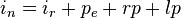

The expected real returns on an investment, before it is made, are:

where:

-

= real interest rate

= real interest rate -

= nominal interest rate

= nominal interest rate -

= expected or projected inflation over the year

= expected or projected inflation over the year

Market interest rates

There is a market for investments which ultimately includes the money market, bond market, stock market, and currency market as well as retail financial institutions like banks.

Exactly how these markets function are sometimes complicated. However, economists generally agree that the interest rates yielded by any investment take into account:

- The risk-free cost of capital

- Inflationary expectations

- The level of risk in the investment

- The costs of the transaction

This rate incorporates the deferred consumption and alternative investments elements of interest.

Inflationary expectations

According to the theory of rational expectations, people form an expectation of what will happen to inflation in the future. They then ensure that they offer or ask a nominal interest rate that means they have the appropriate real interest rate on their investment.

This is given by the formula:

where:

-

= offered nominal interest rate

= offered nominal interest rate -

= desired real interest rate

= desired real interest rate -

= inflationary expectations

= inflationary expectations

Risk

The level of risk in investments is taken into consideration. This is why very volatile investments like shares and junk bonds have higher returns than safer ones like government bonds.

The extra-interest charged on a risky investment is the risk premium. The required risk premium is dependent on the risk preferences of the lender.

If an investment is 50% likely to go bankrupt, a risk-neutral lender will require their returns to double. So for an investment normally returning $100 they would require $200 back. A risk-averse lender would require more than $200 back and a risk-loving lender less than $200. Evidence suggests that most lenders are in fact risk-averse.[13]

Generally speaking, a longer-term investment carries a maturity risk premium, because long-term loans are exposed to more risk of default during their duration.

Liquidity preference

Most investors prefer their money to be in cash than in less fungible investments. Cash is on hand to be spent immediately if the need arises, but some investments require time or effort to transfer into spendable form. This is known as liquidity preference. A 1-year loan, for instance, is very liquid compared to a 10-year loan. A 10-year US Treasury bond, however, is liquid because it can easily be sold on the market.

A market interest-rate model

A basic interest rate pricing model for an asset

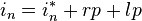

Assuming perfect information, pe is the same for all participants in the market, and this is identical to:

where

- in is the nominal interest rate on a given investment

- ir is the risk-free return to capital

- i*n = the nominal interest rate on a short-term risk-free liquid bond (such as U.S. Treasury Bills).

- rp = a risk premium reflecting the length of the investment and the likelihood the borrower will default

- lp = liquidity premium (reflecting the perceived difficulty of converting the asset into money and thus into goods).

Spread

The spread of interest rates is the lending rate minus the deposit rate.[14] This spread covers operating costs for banks providing loans and deposits. A negative spread is where a deposit rate is higher than the lending rate.[15]

Interest rates in macroeconomics

Elasticity of substitution

The elasticity of substitution (full name should be the marginal rate of substitution of the relative allocation) affects the real interest rate. The larger the magnitude of the elasticity of substitution, the more the exchange, and the lower the real interest rate.

Output and unemployment

Higher interest rates increase the cost of borrowing which can reduce investment and output and increase unemployment. Expanding businesses, especially entrepreneurs tend to be net debtors. However, the Austrian School of Economics sees higher rates as leading to greater investment in order to earn the interest to pay its creditors. Higher rates encourage more saving and reduce inflation.

Open Market Operations in the United States

The Federal Reserve (often referred to as 'The Fed') implements monetary policy largely by targeting the federal funds rate. This is the rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans of federal funds, which are the reserves held by banks at the Fed. Open market operations are one tool within monetary policy implemented by the Federal Reserve to steer short-term interest rates using the power to buy and sell treasury securities.

Money and inflation

Loans, bonds, and shares have some of the characteristics of money and are included in the broad money supply.

By setting i*n, the government institution can affect the markets to alter the total of loans, bonds and shares issued. Generally speaking, a higher real interest rate reduces the broad money supply.

Through the quantity theory of money, increases in the money supply lead to inflation.

Impact on savings and pensions

Financial economists such as World Pensions Council (WPC) researchers have argued that durably low interest rates in most G20 countries will have an adverse impact on the funding positions of pension funds as “without returns that outstrip inflation, pension investors face the real value of their savings declining rather than ratcheting up over the next few years” [16]

From 1982 until 2012, most Western economies experienced a period of low inflation combined with relatively high returns on investments across all asset classes including government bonds. This brought a certain sense of complacency amongst some pension actuarial consultants and regulators, making it seem reasonable to use optimistic economic assumptions to calculate the present value of future pension liabilities.

This potentially long-lasting collapse in returns on government bonds is taking place against the backdrop of a protracted fall in returns for other core-assets such as blue chip stocks, and, more importantly, a silent demographic shock. Factoring in the corresponding "longevity risk", pension premiums could be raised significantly while disposable incomes stagnate and employees work longer years before retiring.[16]

Mathematical note

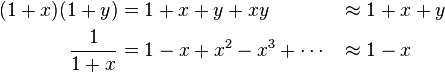

Because interest and inflation are generally given as percentage increases, the formulae above are (linear) approximations.

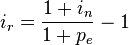

For instance,

is only approximate. In reality, the relationship is

so

The two approximations, eliminating higher order terms, are:

The formulae in this article are exact if logarithmic units are used for relative changes, or equivalently if logarithms of indices are used in place of rates, and hold even for large relative changes. Most elegantly, if the natural logarithm is used, yielding the neper as logarithmic units, scaling by 100 to obtain the centineper yields units that are infinitesimally equal to percentage change (hence approximately equal for small values), and for which the linear equations hold for all values.

Zero interest rate policy

A so-called "zero interest rate policy" (ZIRP) is a very low—near-zero—central bank target interest rate. At this zero lower bound the central bank faces difficulties with conventional monetary policy, because it is generally believed that market interest rates cannot realistically be pushed down into negative territory.

Negative nominal interest rates

Nominal interest rates are normally positive, but not always. In contrast, real interest rates can be negative, when nominal interest rates are below inflation. When this is done via government policy (for example, via reserve requirements), this is deemed financial repression, and was practiced by countries such as the United States and United Kingdom following World War II (from 1945) until the late 1970s or early 1980s (during and following the Post–World War II economic expansion).[17][18] In the late 1970s, United States Treasury securities with negative real interest rates were deemed certificates of confiscation.[19]

On central bank reserves

A so-called "negative interest rate policy" (NIRP) is a negative (below zero) central bank target interest rate.

Theory

Given the alternative of holding cash, and thus earning 0%, rather than lending it out, profit-seeking lenders will not lend below 0%, as that will guarantee a loss, and a bank offering a negative deposit rate will find few takers, as savers will instead hold cash.[20]

Negative interest rates have been proposed in the past, notably in the late 19th century by Silvio Gesell.[21] A negative interest rate can be described (as by Gesell) as a "tax on holding money"; he proposed it as the Freigeld (free money) component of his Freiwirtschaft (free economy) system. To prevent people from holding cash (and thus earning 0%), Gesell suggested issuing money for a limited duration, after which it must be exchanged for new bills; attempts to hold money thus result in it expiring and becoming worthless. Along similar lines, John Maynard Keynes approvingly cited the idea of a carrying tax on money,[21] (1936, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money) but dismissed it due to administrative difficulties.[22] More recently, a carry tax on currency was proposed by a Federal Reserve employee (Marvin Goodfriend) in 1999, to be implemented via magnetic strips on bills, deducting the carry tax upon deposit, the tax being based on how long the bill had been held.[22]

It has been proposed that a negative interest rate can in principle be levied on existing paper currency via a serial number lottery: choosing a random number 0 to 9 and declaring that bills whose serial number end in that digit are worthless would yield a negative 10% interest rate, for instance (choosing the last two digits would allow a negative 1% interest rate, and so forth). This was proposed by an anonymous student of Greg Mankiw,[21] though more as a thought experiment than a genuine proposal.[23]

A much simpler method to achieve negative real interest rates and provide a disincentive to holding cash, is for governments to encourage mildly inflationary monetary policy; indeed, this is what Keynes recommended back in 1936.

Practice

Both the European Central Bank starting in 2014 and the Bank of Japan starting in early 2016 pursued the policy on top of their earlier and continuing quantitative easing policies. The latter's policy was said at its inception to be to be trying to 'change Japan’s “deflationary mindset.”' In 2016 Sweden, Denmark and Switzerland -- not directly participants in the Euro currency zone -- also had NIRPs in place.[24]

Countries such as Sweden and Denmark have set negative interest on reserves—that is to say, they have charged interest on reserves.[25][26][27][28]

In July 2009, Sweden's central bank, the Riksbank, set its policy repo rate, the interest rate on its one-week deposit facility, at 0.25%, at the same time as setting its overnight deposit rate at -0.25%.[29] The existence of the negative overnight deposit rate was a technical consequence of the fact that overnight deposit rates are generally set at 0.5% below or 0.75% below the policy rate.[29][30] This is not technically an example of "negative interest on excess reserves," because Sweden does not have a reserve requirement,[31] but imposing a reserve interest rate without reserve requirements imposes an implied reserve requirement of zero. The Riksbank studied the impact of these changes and stated in a commentary report[32] that they led to no disruptions in Swedish financial markets.

On bond yields

During the European debt crisis, government bonds of some countries (Switzerland, Denmark, Germany, Finland, the Netherlands and Austria) have been sold at negative yields. Suggested explanations include desire for safety and protection against the eurozone breaking up (in which case some eurozone countries might redenominate their debt into a stronger currency).[33]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "INSIGHT-Mild inflation, low interest rates could help economy". Reuters. 2 August 2011.

- ↑ Sepehri, Ardeshir; Moshiri, Saeed (2004). "Inflation‐Growth Profiles Across Countries: Evidence from Developing and Developed Countries". International Review of Applied Economics 18 (2): 191–207. doi:10.1080/0269217042000186679.

- ↑ http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2003/06/pdf/inflatio.pdf

- ↑ "Finance & Development, June 2003 - Contents". Finance and Development - F&D.

- ↑ "Finance & Development, March 2010 - Back to Basics". Finance and Development - F&D.

- ↑ moneyextra.com Interest Rate History. Retrieved 2008-10-27

- ↑ "UK interest rates lowered to 0.5%". BBC News. 5 March 2009.

- ↑ (Homer, Sylla & Sylla 1996, p. 509)

- ↑ Bundesbank. BBK – Statistics – Time series database. Retrieved 2008-10-27

- ↑ worldeconomies.co.uk Zimbabwe currency revised to help inflation

- ↑ (Homer, Sylla & Sylla 1996, p. 1)

- ↑ Commonwealth Bank Why do Interest Rates Change?

- ↑ Benchimol, J., 2014. Risk aversion in the Eurozone, Research in Economics, vol. 68, issue 1, pp. 39-56.

- ↑ Interest rate spread (lending rate minus deposit rate, %) from World Bank. 2012

- ↑ Negative Spread Law & Legal Definition, retrieved January 2013

- 1 2 M. Nicolas J. Firzli quoted in Sinead Cruise (4 August 2012). "'Zero Return World Squeezes Retirement Plans'". Reuters with CNBC (.). Retrieved 5 Aug 2012.

- ↑ William H. Gross. "The Caine Mutiny Part 2 - PIMCO". Pacific Investment Management Company LLC.

- ↑ Financial Repression Redux (Reinhart, Kirkegaard, Sbrancia June 2011)

- ↑ Norris, Floyd (28 October 2010). "U.S. Bonds That Could Return Less Than Their Price". The New York Times.

- ↑ Buiter, Willem (7 May 2009). "Negative interest rates: when are they coming to a central bank near you?". Financial Times blog.

- 1 2 3 Mankiw, N. Gregory (18 April 2009). "It May Be Time for the Fed to Go Negative". The New York Times.

- 1 2 McCullagh, Declan (27 October 1999). "Cash and the 'Carry Tax'". WIRED. Retrieved 2011-12-21.

- ↑ See follow-up blog posts for discussion: "Observations on Negative Interest Rates", 19 April 2009; "More on Negative Interest Rates", 22 April 2009; "More on Negative Interest Rates", 7 May 2009, all in Greg Mankiw's Blog: Random Observations for Students of Economics

- ↑ Nakamichi, Takashi, Megumi Fujikawa and Eleanor Warnock, "Bank of Japan Introduces Negative Interest Rates" (possibly subscription-only), Wall Street Journal, January 29, 2016. Retrieved 2016-01-29.

- ↑ Goodhart, C.A.E. (January 2013). "The Potential Instruments of Monetary Policy" (PDF). Financial Markets Group Paper (Special Paper 219). London School of Economics. 9-10. ISSN 1359-9151. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ Blinder, Alan S. (February 2012). "Revisiting Monetary Policy in a Low-Inflation and Low-Utilization Environment". Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 44 (Supplement s1): 141–146. doi:10.1111/j.1538-4616.2011.00481.x. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ Thoma, Mark (August 27, 2012). "Would Lowering the Interest Rate on Excess Reserves Stimulate the Economy?". Economist's View. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ Parameswaran, Ashwin. "On The Folly of Inflation Targeting In A World Of Interest Bearing Money". Macroeconomic Resilience. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- 1 2 "Repo rate table". Sveriges Riksbank. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ Ward, Andrew; Oakley, David (27 August 2009). "Bankers watch as Sweden goes negative". Financial Times (London).

- ↑ Gray, Simon (February 2011). "Central Bank Balances and Reserve Requirements" (PDF). International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 5 October 2013.

- ↑ Beechey, Meredith; Elmér, Heidi (30 September 2009). "The lower limit of the Riksbank’s repo rate" (PDF). Sveriges Riksbank. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ Wigglesworth, Robin (18 July 2012). "Schatz yields turn negative for first time". Financial Times (London).

References

- Homer, Sidney; Sylla, Richard Eugene; Sylla, Richard (1996). A History of Interest Rates. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-2288-3. Retrieved 2008-10-27.

- Malkiel, Burton G. (2008). "Interest Rates". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||