Negative gearing

Negative gearing is a practice whereby an investor borrows money to acquire an income-producing investment property, expecting the gross income generated by the investment, at least in the short-term, to be less than the cost of owning and managing the investment, including depreciation and interest charged on the loan (but excluding capital repayments). The arrangement is a form of financial leverage. The investor may enter into this arrangement expecting the tax benefits (if any) and the capital gain on the investment, when the investment is ultimately disposed of, to exceed the accumulated losses of holding the investment.

The tax treatment of negative gearing would be a factor which the investor would take into account in entering into the arrangement, which may generate additional benefits to the investor in the form of tax benefits if the loss on a negatively geared investment is tax-deductible against the investor's other taxable income, and if the capital gain on the sale is given a favourable tax treatment. Some countries, including Australia, Japan and New Zealand allow unrestricted use of negative gearing losses to offset income from other sources. Several other OECD countries, including the USA, Germany, Sweden, and France, allow loss offsetting with some restrictions. In Canada losses cannot be offset against wages or salaries. Applying tax deductions from negatively geared investment housing to other income is not permitted in the UK or the Netherlands.[1] With respect to investment decisions and market prices, other taxes such as stamp duties and capital gains tax may be more or less onerous in those countries, increasing or decreasing the attractiveness of residential property as an investment.[2]

Another example of negative gearing is borrowing to purchase shares whose dividends fall short of interest costs. A common type of loan to finance such a transaction is called a margin loan. The tax treatment may or may not be the same.

Negative gearing is a form of leveraged investment. In a few countries the strategy is motivated by taxation systems that permit deduction of losses against taxed income, and tax capital gains at a lower rate. When income generated does cover the interest it is simply a geared investment which creates passive income.

A negative gearing strategy makes a profit under the following circumstances:

1. If the asset rises in value so that the capital gain is more than the sum of the ongoing losses over the life of the investment; or

2. If the income stream rises to become greater than the cost of interest (i.e. the investment becomes positively geared); or

3. If the interest cost falls due to lower interest rates or paying down the principal of the loan (again, making the investment positively geared).

The investor must be able to fund any shortfall until the asset is sold, or until the investment becomes positively geared (income > interest). The different tax treatment of planned ongoing losses and possible future capital gains affects the investor's final return. This leads to a situation in the countries which tax capital gains at a lower rate than income. In those countries it is possible for an investor to make a loss overall before taxation, but a small gain after taxpayer subsidies.

Deduction of negative gearing losses on property against income from other sources is permitted in several countries, including Canada, Australia and New Zealand. A negatively geared investment property will generally only remain negatively geared for several years, after which the rental income will have increased with inflation to the point where the investment is positively geared (the rental income is greater than the interest cost). Positive Gearing occurs when you borrow to invest in an income producing asset and the returns (income) from that asset exceed the cost of borrowing. From this point in time, the investor must pay tax on the rental income profit until the asset is sold, at which point the investor must pay Capital Gains Tax on any sale profit.

Australia

In Australia, negative gearing by property investors reduced personal income tax revenue in Australia by $600 million in the 2001/02 tax year, $3.9 billion in 2004/05 and $13.2 billion in 2010/11.

Taxation

Australian tax treatment of negative gearing is as follows:

- Interest on an investment loan for an income producing purpose is fully deductible if the income falls short of the interest payable. This shortfall can be deducted for tax purposes from income from other sources, such as the wage or salary income of the investor.

- Ongoing maintenance and small expenses are similarly fully deductible.

- Property fixtures and fittings are treated as plant, and a deduction for depreciation is allowed, based on effective life. When later sold the difference between actual proceeds and the written-down value becomes income, or further deduction.

- Capital works (buildings or major additions, constructed after 1997 or certain other dates) attract a 2.5% per annum capital works deduction (or 4% in certain circumstances). The percentage is calculated on the initial cost (or an estimate thereof), and can be claimed until the cost of the works has been completely recovered. The investor's cost base for capital gains tax purposes is reduced by the amount claimed.

- On sale, or most other methods of transfer of ownership, capital gains tax is payable on the proceeds minus cost base (and excluding items treated as plant above). A net capital gain is taxed as income, but if the asset was held for one year or more, then the gain is first discounted by 50% for an individual, or 331⁄3% for a superannuation fund. (This discount commenced in 1999, prior to that a cost base indexing and a stretching of marginal rates applied instead.)

The tax treatment of negative gearing and capital gains may benefit investors in a number of ways, including:

- Losses are deductible in the financial year they are incurred, providing nearly immediate benefit.

- Capital gains are taxed in the financial year when a transfer of ownership occurs (or other less common triggering event), which may be many years after the initial deductions.

- If held for more than twelve months, only 50% of the capital gain is taxable.

- Transfer of ownership may be deliberately timed to occur in a year when the investor is subject to a lower marginal tax rate, reducing the applicable capital gains tax rate compared to the tax rate saved by the initial deductions.

However, in certain situations the tax rate applied to the capital gain may be higher than the rate of tax saving due to the initial deductions. For example, if the investor has a low marginal tax rate while making deductions but a high marginal rate in the year the capital gain is realised.

In contrast, the tax treatment of real estate by owner-occupiers differs from investment properties. Mortgage interest and upkeep expenses on a private property are not deductible, but any capital gain (or loss) made on disposal of a primary residence is tax-free. (Special rules apply on a change from private use to renting, or back, and for what is considered a main residence.)

Social matters

The economic and social effects of negative gearing in Australia are a matter of ongoing debate. Those in favour of negative gearing say that:

- Negatively geared investors support the private residential tenancy market, assisting those who cannot afford to buy, and reducing demand on government public housing.

- Investor demand for property supports the building industry, creating employment.(Highly contentious)

- Tax benefits encourage individuals to invest and save, especially to help them become self-sufficient in retirement.

- Startup losses are accepted as deductions for business, and should also be accepted for investors, since investors will be taxed on the result.

- Interest expenses deductible by the investor are income for the lender, so there is no loss of tax revenue.

- Negatively geared properties are running at an actual loss to the investor: even though the loss may be used to reduce tax, the investor is still in a net worse position compared to not owning the property. The investor is expecting to make a profit only on the capital gain when the property is sold, and it is at this point that the treatment of the income is favoured by the tax system, since the only half of the capital gain is assessed as taxable income, providing the investment is held for at least twelve months (before 2000–2001, only the real value of the capital gain was taxed, which had a similar effect). From this perspective, distortions are generated by the fifty percent discount on capital gains income for income tax purposes, not negative gearing.

Opponents of negative gearing argue that:

- It encourages over-investment in residential property, an essentially "unproductive" asset, which is an economic distortion.

- Investors inflate the residential property market, making it less affordable for first home buyers or other owner-occupiers.

- In Australia in 2007, nine out of ten negatively geared properties were existing dwellings, so the creation of rental supply comes almost entirely at the expense of displacing potential owner-occupiers. Thus, if negative gearing is to exist, it should only be applied to newly constructed properties.

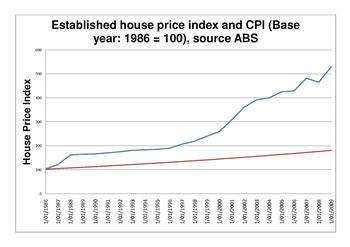

- It encourages speculators into the property market, inflating for instance the Australian property bubble that began in the mid-1990s, partly the result of increased availability of credit that occurred following the entry of non-bank lenders into the Australian mortgage market.

- Tax deductions and overall benefits accrue to those who already have high incomes. This will make the rich investors even richer and the poorer population even poorer, possibly creating and prolonging a social divide between socioeconomic classes.

- Tax deductions reduce government revenue by a significant amount each year, which either represents non-investors subsidising investors, or makes the government less able to provide other programs.

- A negatively geared property never generates net income, so losses should not be deductible. Deductibility of business losses when there is a reasonable expectation of gaining income is a well-accepted principle, but the argument against negative gearing is that it will never generate income. Opponents of full deductibility would presumably at least allow losses to be capitalised into the investor's cost base.

Political history

In July 1985, the Hawke/Keating government quarantined negative gearing interest expenses (on new transactions), so interest could only be claimed against rental income, not other income. (Any excess could be carried forward for use in later years.) What is less appreciated is that Hawke/Keating introduced negative gearing only six months prior. Previous to their initial decision the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (As Amended) had quarantined all property losses from deduction against income from personal exertion (other business or salary and wage income). Any losses incurred in any one year would be accumulated on a register and would only be allowed as a deduction from income from property in succeeding years. In so doing property income and property losses were in one 'bucket' and personal exertion income and losses were in another 'bucket'.

This ensured that either at personal level and more importantly at a national level, that property losses would not be subsidized by income from personal exertion. In applying this formula, all previous governments thereby isolated and consequently discouraged capital speculation being subsidized from the general income tax receipts pool.

Keating initially changed this legislative treatment only months prior to attempting to revert to the original. Politically, those who took immediate benefit from the initial change made false claims that any attempt to remedy the situation would give rise to an explosive increase in rents. There was no statistical or real world data to support this claim, other than localised increases in real rents in both Perth and Sydney which also happened to have the lowest vacancy rates of all capital cities at the time.[3] This was enough to have Hawke/Keating submit to the landlords' demands and remove the attempt at repairing the initial decision.

This is what is described below as a dampening of 'investor enthusiasm', which is not quite the context, as the previous rules (which Keating had first removed and then quickly attempted to reinstate) had been in place since 1936. The argument that somehow investor enthusiasm had been dampened is a shallow argument as negative gearing had not existed in all the time of the ITAA's existence and had only had a very short life to that point and only after Keating's initial amendments to the previous long standing practice. After intense lobbying by the property industry, which claimed that the changes to negative gearing had caused investment in rental accommodation to dry up and rents to rise, the government again amended the ITAA to re-include Keating's changes to the previous legislation, thereby once again permitting the deduction of interest and other rental property costs from other income sources.

An alternative view

The view that the temporary removal of negative gearing caused rents to rise has been challenged by Saul Eslake, who has been quoted as saying, "It's true, according to Real Estate Institute data, that rents went up in Sydney and Perth. But the same data doesn't show any discernible increase in the other state capitals. I would say that, if negative gearing had been responsible for a surge in rents, then you should have observed it everywhere, not just two capitals. In fact, if you dig into other parts of the REI database, what you find is that vacancy rates were unusually low at that time before negative gearing was abolished." [4]

While Saul Eslake's comment is correct for inflation adjusted rents (i.e. when CPI inflation is subtracted from the nominal rent increases), nominal rents nationally did rise by over 25% during the two years when negative gearing was quarantined. Nominal rents rose strongly in every Australian capital city, according to the official ABS CPI Data. However it has not been proved that this strong rise in rents was entirely a direct result of the negative gearing quarantine.[5]

Further as negative gearing had not previously existed at all prior to Keating's initial amendment to the Act, it is a very difficult argument to say that its short term absence in this period of indecision had any effect on property values. Prior to this period there was no such thing as negative gearing, all property losses had always been quarantined from deduction against income from personal exertion and could only be deducted against future profits/income from property sources.

With some irony, it is a return to this treatment (to quarantine losses) that comprised the Centre-point of the Crawford Reports arguments in dealing with property losses and the removal of negative gearing.

Further and later commentary from Saul Eslake and others has highlighted the preponderance of negatively geared purchases in established suburbs where the probability of a lightly taxed capital gain exists and therefore the debunking of the myth that negative gearing leads to new construction. Many economists [6] have commented extensively on the tax subsidy being made available to speculative buyers in competition against home buyers, who have no such tax subsidy, leading to significant social dislocation.

What is not broadly realised is that the tax subsidy feeding into higher home prices adds to the wealth of those taking advantage of negative gearing. The process which crowds out domestic home owners by pushing up the price of housing also automatically makes the successful user of negative gearing more asset rich via the increase in land value, which perversely then allows the same people to borrow even more funds against equity in the previously acquired properties - resulting in even more acquisitions under tax subsidy, which further exacerbate the problems for those seeking to become owner-occupiers.

This clearly leads to heavy economic and social dislocation and creates a property bubble to which the banks are clearly vulnerable. This represents both a danger to future economic stability and, by the introduction of powerful vested interests (the banks) to this speculative equation, a potential limitation of financial and budgetary settings which we have seen from recent overseas experience will blight the lives of many to favour the few.

Effect on housing affordability

In 2003, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) stated in their submission to the Productivity Commission First Home Ownership Inquiry, "there are no specific aspects of current tax arrangements designed to encourage investment in property relative to other investments in the Australian tax system". However, they went on to say, "most sensible area to look for moderation of demand is among investors," and, "the taxation treatment in Australia is more favourable to investors than is the case in other countries." "In particular, the following areas appear worthy of further study by the Productivity Commission: 1. ability to negatively gear an investment property when there is little prospect of the property being cash-flow positive for many years; 2. benefit investors receive when property depreciation allowances are 'clawed back' through the capital gains tax; 3. general treatment of property depreciation, including the ability to claim depreciation on loss-making investments."[7]

In 2008, the Senate Housing Affordability report echoed the findings of the 2004 Productivity Commission report. One recommendation to the enquiry suggested that negative gearing should be capped and that "There should not be unlimited access. Millionaires and billionaires should not be able to access it, and you should not be able to access it on your 20th investment property. There should be limits to it.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ "Quarantining Interest Deductions for Negatively Geared Rental Property Investments" [2005]

- ↑ Housing and Housing Finance: The View from Australia and Beyond, RBA [2006]

- ↑ http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-05-06/hockey-negative-gearing/6431100

- ↑ http://www.abc.net.au/lateline/content/2003/s991144.htm

- ↑ http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/6401.0Mar%202013

- ↑ "Negative Gearing Facts title". Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ↑ RBA Submission to Productivity Commission Inquiry - First Home Ownership

- ↑ 2008 Senate Housing Affordability report Chapter 4.57

External links

- Australian Democrats Negative Gearing Issue Sheet for the 2004 Election (PDF)

- Australian Taxation Office Rental Properties Guide 2005, product NAT 1729-6.2005

- Real Estate Institute of Australia Policy Statement on Negative Gearing, as of October 2005

- Negative gearing: The three facts that will challenge your assumptions, Property Observer, 2013

See also

- Negative gearing (Australia)

- Debt

- Financial engineering

- Investment

- Leveraged buyout

- Margin (finance)

- Return on margin

- Rent seeking

- Speculation

External links

- Negative Gearing Issue Sheet for the Australian federal election, 2004

- Australian Taxation Office Rental Properties Guide 2005, product NAT 1729-6.2005

- Real Estate Institute of Australia Policy Statement on Negative Gearing, as of October 2005

- Negative Gearing—A Commentary on how it works and who it is suited to

- Negative Gearing — A Brief Overview of Negative Gearing In Australia and why people choose to do it: (Accountants, Caringbah Sydney, Australia)