Necrotizing fasciitis

| Necrotizing fasciitis | |

|---|---|

|

Person with necrotizing fasciitis. The left leg shows extensive redness and necrosis. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| ICD-10 | M72.6 |

| ICD-9-CM | 728.86 |

| DiseasesDB | 31119 |

| MedlinePlus | 001443 |

| eMedicine | emerg/332 derm/743 |

| MeSH | D019115 |

Necrotizing fasciitis (/ˈnɛkrəˌtaɪzɪŋ ˌfæʃiˈaɪtɪs/ or /ˌfæs-/), also spelled necrotising fasciitis and abbreviated NF, commonly known as flesh-eating disease, flesh-eating bacteria or flesh-eating bacteria syndrome,[1] is a rare infection of the deeper layers of skin and subcutaneous tissues, easily spreading across the fascial plane within the subcutaneous tissue. The most consistent feature of necrotizing fasciitis was first described in 1952 as necrosis of the subcutaneous tissue and fascia with relative sparing of the underlying muscle.[2]

Necrotizing fasciitis progresses rapidly, having greater risk of developing in the immunocompromised due to conditions such as diabetes or cancer. It is a severe disease of sudden onset and is usually treated immediately with surgical debridement and large doses of intravenous antibiotics,[3] with delay in surgical treatment being associated with higher mortality.

Many types of bacteria can cause necrotizing fasciitis (e.g., Group A streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes), Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium perfringens, Bacteroides fragilis, Vibrio vulnificus, Aeromonas hydrophila[4]). The disease is classified as Type I (polymicrobial, due to a number of different organisms) or Type II (monomicrobial, due to a single infecting organism). The majority of cases of necrotizing fasciitis are polymicrobial, with 25–45% of cases being Type II.[5] Such infections are more likely to occur in people with compromised immune systems secondary to chronic disease.[6]

Historically, most cases of Type II infections have been due to group A streptococcus and staphylococcal species. Since as early as 2001, a form of monomicrobial necrotizing fasciitis which is particularly difficult to treat has been observed with increasing frequency[7] caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Possible sources

The majority of infections are caused by organisms that normally reside on the individual's skin. These skin flora exist as commensals and infections reflect their anatomical distribution (e.g. perineal infections being caused by anaerobes). Historically, foot binding in China also was a cause, most likely as animal blood and herbs were used to soak the binding cloths and feet at each binding session.

Sources of MRSA may include eating undercooked contaminated meats,[8] working at municipal waste water treatment plants, exposure to secondary waste water spray irrigation,[9] consuming raw products produced from farm fields fertilized by human sewage sludge or septage, in hospital settings from people with weakened immune systems,[10] or sharing/using dirty needles.[11] The risk of infection during regional anesthesia is considered to be very low, though reported.[12]

Signs and symptoms

Over 70% of cases are recorded in people with at least one of the following clinical situations: immunosuppression, diabetes, alcoholism/drug abuse/smoking, malignancies, and chronic systemic diseases. For reasons that are unclear, it occasionally occurs in people with an apparently normal general condition.[13]

The infection begins locally at a site of trauma, which may be severe (such as the result of surgery), minor, or even non-apparent. People usually complain of intense pain that may seem excessive given the external appearance of the skin. People initially have signs of inflammation, fever and a fast heart rate. With progression of the disease, often within hours, tissue becomes progressively swollen, the skin becomes discolored and develops blisters. Crepitus may be present and there may be discharge of fluid, said to resemble "dish-water". Diarrhea and vomiting are also common symptoms.

In the early stages, signs of inflammation may not be apparent if the bacteria are deep within the tissue. If they are not deep, signs of inflammation, such as redness and swollen or hot skin, develop very quickly. Skin color may progress to violet, and blisters may form, with subsequent necrosis (death) of the subcutaneous tissues.

Furthermore, people with necrotizing fasciitis typically have a fever and appear very ill. Mortality rates have been noted as high as 73 percent if left untreated.[14] Without surgery and medical assistance, such as antibiotics, the infection will rapidly progress and will eventually lead to death.[15]

Pathophysiology

"Flesh-eating bacteria" is a misnomer, as in truth, the bacteria do not "eat" the tissue. They destroy the tissue that makes up the skin and muscle by releasing toxins (virulence factors), which include streptococcal pyogenic exotoxins.

Diagnosis

The Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) score can be utilized to risk stratify people having signs of cellulitis to determine the likelihood of necrotizing fasciitis being present. It uses six serologic measures: C-reactive protein, total white blood cell count, hemoglobin, sodium, creatinine and glucose. A score greater than or equal to[16] 6 indicates that necrotizing fasciitis should be seriously considered. The scoring criteria are as follows:

- CRP (mg/L) ≥150: 4 points

- WBC count (×103/mm3)

- <15: 0 points

- 15–25: 1 point

- >25: 2 points

- Hemoglobin (g/dL)

- >13.5: 0 points

- 11–13.5: 1 point

- <11: 2 points

- Sodium (mmol/L) <135: 2 points

- Creatinine (umol/L) >141: 2 points

- Glucose (mmol/L) >10: 1 point[17][18]

As per the derivation study of the LRINEC score, a score of ≥ 6 is a reasonable cut-off to rule in necrotizing fasciitis, but a LRINEC < 6 does not completely rule out the diagnosis. Diagnoses of severe cellulitis or abscess should also be considered due to similar presentations.[19] 10% of patients with necrotizing fasciitis in the original study still had a LRINEC score < 6.[20] But a validation study showed that patients with a LRINEC score ≥6 have a higher rate of both mortality and amputation.[21]

Treatment

Early medical treatment is often presumptive; thus, antibiotics should be started as soon as this condition is suspected. Initial treatment often includes a combination of intravenous antibiotics including piperacillin/tazobactam, vancomycin, and clindamycin. Cultures are taken to determine appropriate antibiotic coverage, and antibiotics may be changed when culture results are obtained.

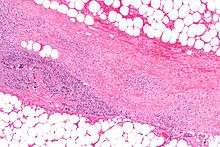

People are typically taken to surgery based on a high index of suspicion, determined by the person's signs and symptoms. In necrotizing fasciitis, aggressive surgical debridement (removal of infected tissue) is always necessary to keep it from spreading and is the only treatment available. Diagnosis is confirmed by visual examination of the tissues and by tissue samples sent for microscopic evaluation.

As in other maladies characterized by massive wounds or tissue destruction, hyperbaric oxygen treatment can be a valuable adjunctive therapy but is not widely available.[22] Amputation of the affected limb(s) may be necessary. Repeat explorations usually need to be done to remove additional necrotic tissue. Typically, this leaves a large open wound, which often requires skin grafting, though necrosis of internal (thoracic and abdominal) viscera – such as intestinal tissue – is also possible. The associated systemic inflammatory response is usually profound, and most people will require monitoring in an intensive care unit. Because of the extreme nature of many of these wounds and the grafting and debridement that accompanies such a treatment, a burn center's wound clinic, which has staff trained in such wounds, may be utilized.

Treatment for necrotizing fasciitis may involve an interdisciplinary care team. For example, in the case of a necrotizing fasciitis involving the head and neck, the team could include otolaryngologists, speech pathologists, intensivists, microbiologists and plastic surgeons or oral and maxillofacial surgeons.[23] Maintaining strict asepsis during any surgical procedure and regional anaesthesia techniques is vital in preventing the occurrence of the disease.[24]

Notable cases

- 1994 Lucien Bouchard, former premier of Québec, Canada, who became infected in 1994 while leader of the federal official opposition Bloc Québécois party, lost a leg to the illness.[25]

- 1994 A cluster of cases occurred in Gloucestershire, in the west of England. Of five confirmed and one probable infection, two died. The cases were believed to be connected. The first two had acquired the Streptococcus pyogenes bacteria during surgery, the remaining four were community-acquired.[26] The cases generated much newspaper coverage, with lurid headlines such as "Flesh Eating Bug Ate My Face".[27]

- 1997 Ken Kendrick, former agent and partial owner of the San Diego Padres and Arizona Diamondbacks, contracted the disease in 1997. He had seven surgeries in a little more than a week and later recovered fully.[28]

- 2004 Eric Allin Cornell, winner of the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physics, lost his left arm and shoulder to the disease in 2004.[29]

- 2005 Alexandru Marin, an experimental particle physicist, professor at MIT, Boston University and Harvard University, and researcher at CERN and JINR, died from the disease.[30]

- 2006 David Walton, a leading economist in the UK and a member of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee, died in June 2006 of the disease within 24 hours of diagnosis.[31]

- 2006 Alan Coren, British writer and satirist, announced in his Christmas 2006 column for The Times that his long absence as a columnist had been caused by his contracting the disease while on holiday in France.[32]

- 2009 (November) Eric Seitz – Formerly homeless youth living on the streets of Seattle, Portland and Vancouver, who after a harrowing experience with NF, was inspired to pursue nursing. Eric Seitz, a second-year Bachelor of Science in Nursing Student (BSN), woke up on Thanksgiving Day 2009 in Harborview Medical Center, where he had been in a coma for a month. The doctors told his family he had a 5% chance of living, and a 50% chance of losing both limbs. After 3 months of hospitalization and therapy, he left the hospital and began to pursue nursing school to help prevent those on the streets, who are at risk of necrotizing soft tissue infections from getting the condition.[33]

- 2009 R. W. Johnson, South African journalist and historian, contracted the disease in March 2009 after injuring his foot while swimming. His leg was amputated above the knee.[34]

- 2011 (January) Jeff Hanneman, guitarist for the thrash metal band Slayer, contracted the disease in 2011. He died of liver failure two years later, on May 2, 2013, and it was speculated his infection might be the cause of death. However, on May 9, 2013, the official cause of death was announced as alcohol-related cirrhosis. Hanneman and his family had apparently been unaware of the extent of the condition until shortly before his death.[35]

- 2011 (February) Peter Watts, Canadian science fiction author, contracted the disease in early 2011. On his blog, Watts reported, "I’m told I was a few hours away from being dead...If there was ever a disease fit for a science fiction writer, flesh-eating disease has got to be it. This...spread across my leg as fast as a Star Trek space disease in time-lapse."[36]

- 2012 (May) Aimee Copeland, a 24-year-old graduate student, contracted necrotizing fasciitis after she fell from a zip-line into the Little Tallapoosa River which caused a deep cut in her leg. Copeland’s entire leg was amputated along with her other limbs as a side effect of the disease and treatment.[37] Five of her organs also failed as a result of the ordeal.[38]

- 2012 (December) Mary Ryan from Florida – originally from Cork, Ireland – underwent liposuction on her abdomen, neck and jowls on December 19. After the procedure she complained about extreme nausea and pain in her abdomen, and because of this she failed to attend a scheduled post-op checkup. As she reported feeling better, she traveled to Ireland on December 24 to visit her family. However, she did not travel with the prescribed antibiotics due to a communication breakdown. On arrival at her son's home on December 26 she reported feeling very ill. After consulting a local GP, Mrs. Ryan was admitted to the Intensive Care department of Cork University Hospital the same evening. Despite surgical intervention and high doses of antibiotics she died on December 29, only ten days after the liposuction treatment. The coroner's verdict was 'death by medical misadventure'.[39]

- 2013 Rick Teal, New Zealand father of three, was at work when he noticed a nagging pain in his right leg. Within half an hour he had developed a limp. He was subsequently admitted to Wellington Hospital and, two days after the onset of symptoms, he gave doctors permission to amputate his leg. Teal eventually recovered without amputation but large areas of infected flesh between his knee and ankle had to be debrided. Necrotizing fasciitis is on the rise in New Zealand.[40]

- 2014 Don Rickles, a celebrated American stand-up comedian (b. 8 May 1926), revealed on The Late Show with David Letterman on 2 May 2014 that he had contracted necrotizing fasciitis on his right leg. His doctor came over to his house for a visit and noticed a sore on Don's leg. After examining it he sent him straight to the hospital. Treatment was successful, though he now requires a cane for a short period of time. If it had progressed further, Don quipped, he would have wound up with Johnny Depp as a one legged pirate.[41]

- 2015 (may) Edgar Savisaar, an Estonian politician. His right leg was amputated. He got the disease during a trip to Thailand.[42]

Note: It is often incorrectly reported that Jim Henson, creator of the Muppets, died of necrotizing fasciitis. In fact he died of toxic shock syndrome caused by Streptococcus pyogenes.

See also

- Mucormycosis, a rare fungal infection that can present like necrotizing fasciitis.

- Toxic shock syndrome

- Fournier gangrene

- Vibrio vulnificus[43] warm saltwater flesh-eating bacteria.

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

References

- ↑ Rapini RP, Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 1-4160-2999-0.

- ↑ Wilson, B (April 1952). "Necrotising Fasciitis". Am Surg 18 (4): 416–31. PMID 14915014.

- ↑ Jain A, Varma A, Mangalanandan Kumar PH, Bal A (2009). "Surgical outcome of necrotizing fasciitis in diabetic lower limbs". Journal of Diabetic Foot Complications 1 (4): 80–84.

- ↑ http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/n/a/2012/05/16/national/a145331D94.DTL&tsp=1 Archived May 19, 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Sarani, Babak; Strong, Michelle; Pascual, Jose; Schwab, C. William (2009). "Necrotizing Fasciitis: Current Concepts and Review of the Literature". Journal of the American College of Surgeons 208 (2): 279–288. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.10.032. ISSN 1072-7515.

- ↑ Kotrappa KS, Bansal RS, Amin NM (April 1996). "Necrotizing fasciitis". American Family Physician 53 (5): 1691–1697. PMID 8623695.

- ↑ Lee TC, Carrick MM, Scott BG, et al. (2007). "Incidence and clinical characteristics of methicillin-resistant fasciitis in a large urban hospital". American Journal of Surgery 194 (6): 809–13. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.08.047. PMID 18005776.

- ↑ "MRSA found in meat".

- ↑ "MRSA found in wastewater byproducts" (PDF).

- ↑ "MRSA in hospitals".

- ↑ "MRSA from sharing or using dirty needles".

- ↑ Singh, Raj Kumar, and Gautam Dutta. "Fatal necrotising fasciitis after spinal anaesthesia." Journal of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery 6.3 (2013): 165.

- ↑ Pricop M, Urechescu H, Sîrbu A, Urtilă E (Mar 2011). "Fasceita necrozantă cervico-toracică: caz clinic și recenzie a literaturii de specialitate" [Necrotizing cervical fasciitis: clinical case and review of literature]. Revista de chirurgie oro-maxilo-facială și implantologie [Journal of oro-maxillo-facial surgery and implantology] (in Romanian) 2 (1): 1–6. ISSN 2069-3850. 17. Retrieved 2012-04-10.(webpage has a translation button)

- ↑ Trent JT, Kirsner RS (2002-11-25). "Necrotizing Fasciitis". Medscape.

- ↑ "Necrotizing Fasciitis (Flesh-Eating Bacteria)". WebMD. 2011-10-12.

- ↑ Crit Care Med. 2004 Jul;32(7):1535-41.The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections.

- ↑ Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, Tan KC, Low CO (2004). "The LRINEC Laboratory Rother soft tissue infections". Critical Care Medicine 32 (7): 1535–1541. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000129486.35458.7D. PMID 15241098.

- ↑ "LRINEC scoring system for necrotising fasciitis". EMT Emergency Medicine Tutorials.

- ↑ "LRINEC Score for Necrotiing Fasciitis". MDCalc. Retrieved 2014-11-15.

- ↑ Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, Tan KC, Low CO (2004). "The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections.". Crit Care Med. 32 (7): 1535–41. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000129486.35458.7D. PMID 15241098.

- ↑ Su YC, Chen HW, Hong YC, Chen CT, Hsiao CT, Chen IC. (2008). "Laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis score and the outcomes.". ANZ J Surg. 78 (11): 968–72. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2008.04713.x. PMID 18959694.

- ↑ Escobar SJ, Slade JB, Hunt TK, Cianci P (2005). "Adjuvant hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO2) for treatment of necrotizing fasciitis reduces mortality and amputation rate". Undersea Hyperb Med 32 (6): 437–43. PMID 16509286. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ↑ Malik V; Gadepalli, C; Agrawal, S; Inkster, C; Lobo, C (2010). "An Algorithm for Early Diagnosis of Cervicofacial Necrotizing Fasciitis". Eur Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 267 (8): 1169–77. doi:10.1007/s00405-010-1248-5. PMID 20396897.

- ↑ "Fatal Necrotising Fasciitis After Spinal Anaesthesia". Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 2014-01-24. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- ↑ The Once and Future Scourge

- ↑ Cartwright, K.; Logan, M.; McNulty, C.; Harrison, S.; George, R.; Efstratiou, A.; McEvoy, M.; Begg, N. (December 1995). "A cluster of cases of streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis in Gloucestershire". Epidemiol Infect. 3 187 (3): 387–397. PMC 2271581. PMID 8557070.

- ↑ Dixon, Bernhard (11 March 1996). "Microbe of the Month: What became of the flesh-eating bug?". Independent. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ↑ "Moorad's life changed by rare disease

- ↑ Cornell Discusses His Recovery from Necrotizing Fasciitis with Reporters

- ↑ "In Memoriam – Alexandru A. Marin (1945–2005)", ATLAS eNews, December 2005 (accessed 5 November 2007).

- ↑ "Flesh-eating bug killed top economist in 24 hours". Mail Online. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ "Opinion - The Times". timesonline.co.uk. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ "UW-360 February 2014 - Homeless Nurse". UWTV. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ R. W. Johnson "Diary", London Review of Books, 6 August 2009, p41

- ↑ "Slayer Guitarist Jeff Hanneman: Official Cause Of Death Revealed - May 9, 2013". Blabbermouth.net. Roadrunner Records. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Plastinated Man". rifters.com. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ "UWG student in 'dire' condition after zip line injury". Tallapoosa-Journal.com. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ↑ "Aimee's Accident". Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ↑ Irish Independent: Woman killed by flesheating bug, 28 June 2013. Visited: 1 July 2013

- ↑ Michelle Robinson. "Family Counts Blessings After Superbug Scare". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 2013-10-01.

- ↑ YouTube. youtube.com. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ↑ News in estonian about Edgar Savisaars leg amputation.

- ↑ ABCNews July 30, 2014: "Dangerous bacteria: Vibro Vulnificus in Florida ocean hospitalizes 32, kills 10"

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||