Nearly free electron model

In solid-state physics, the nearly free electron model (or NFE model) is a quantum mechanical model of physical properties of electrons that can move almost freely through the crystal lattice of a solid. The model is closely related to the more conceptual Empty Lattice Approximation. The model enables understanding and calculating the electronic band structure of especially metals.

Introduction - a heuristic argument

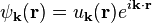

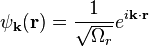

Free electrons are traveling plane waves. Generally the time independent part of their wave function is expressed as

These plane wave solutions have an energy of

The expression of the plane wave as a complex exponential function can also be written as the sum of two periodic functions which are mutually shifted a quarter of a period.

In this light the wave function of a free electron can be viewed as the sum of two plane waves. Sine and cosine functions can also be expressed as sums or differences of plane waves moving in opposite directions

Assume that there is only one kind of atom present in the lattice and that the atoms are located at the lattice points. The potential of the atoms is attractive (negative) and concentrated near the lattice points. In the remainder of the cell the potential is close to zero.

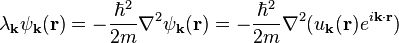

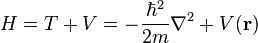

The Hamiltonian is expressed as

in which  is the kinetic and

is the kinetic and  is the potential energy. From this expression the energy expectation value, or the statistical average, of the energy of the electron can be calculated with

is the potential energy. From this expression the energy expectation value, or the statistical average, of the energy of the electron can be calculated with

where we integrate in  over a single lattice cell. If we assume that the electron is given by a plane wave of wave number

over a single lattice cell. If we assume that the electron is given by a plane wave of wave number  (despite the nonconstant potential

(despite the nonconstant potential  ), the energy of the electron is:

), the energy of the electron is:

This means that at each  the energy is lowered below the free space value by the average

the energy is lowered below the free space value by the average  of the attractive potential of the atom. If the potential is very small we get the Empty Lattice Approximation. This isn't a very sensational result and it doesn't say anything about what happens when we get close to the Brillouin zone boundary. We will look at those regions in

of the attractive potential of the atom. If the potential is very small we get the Empty Lattice Approximation. This isn't a very sensational result and it doesn't say anything about what happens when we get close to the Brillouin zone boundary. We will look at those regions in  -space now.

-space now.

Let's assume that we look at the problem from the origin, at position  . If

. If  only the cosine part is present and the sine part is moved to

only the cosine part is present and the sine part is moved to  . If we let the length of the wave vector

. If we let the length of the wave vector  grow, then the central maximum of the cosine part stays at

grow, then the central maximum of the cosine part stays at  . The first maximum and minimum of the sine part are at

. The first maximum and minimum of the sine part are at  . They come nearer as

. They come nearer as  grows. Let's assume that

grows. Let's assume that  is close to the Brillouin zone boundary for the analysis in the next part of this introduction.

is close to the Brillouin zone boundary for the analysis in the next part of this introduction.

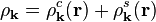

The atomic positions coincide with the maximum of the  -component of the wave function. The interaction of the

-component of the wave function. The interaction of the  -component of the wave function with the potential will be different from the interaction of the

-component of the wave function with the potential will be different from the interaction of the  -component of the wave function with the potential because their phases are shifted. The charge density

-component of the wave function with the potential because their phases are shifted. The charge density  is proportional to the absolute value squared,

is proportional to the absolute value squared,  , of the wave function. It is useful to split it into two parts,

, of the wave function. It is useful to split it into two parts,  , coming from the

, coming from the  and

and  -components. For the former component it is

-components. For the former component it is

and for the  -component it is

-component it is

For values of  close to the Brillouin zone boundary, the length of the two waves and the period of the two different charge density distributions almost coincide with the periodic potential of the lattice. As a result the charge densities of the two components have a different energy because the maximum of the charge density of the

close to the Brillouin zone boundary, the length of the two waves and the period of the two different charge density distributions almost coincide with the periodic potential of the lattice. As a result the charge densities of the two components have a different energy because the maximum of the charge density of the  -component coincides with the attractive potential of the atoms while the maximum of the charge density of the

-component coincides with the attractive potential of the atoms while the maximum of the charge density of the  -component lies in the regions with a higher electrostatic potential between the atoms.

-component lies in the regions with a higher electrostatic potential between the atoms.

As a result the aggregate will be split in high and low energy components when the kinetic energy increases and the wave vector approaches the length of the reciprocal lattice vectors. The potentials of the atomic cores can be decomposed into Fourier components to meet the requirements of a description in terms of reciprocal space parameters.

Mathematical formulation

The nearly free electron model is a modification of the free-electron gas model which includes a weak periodic perturbation meant to model the interaction between the conduction electrons and the ions in a crystalline solid. This model, like the free-electron model, does not take into account electron-electron interactions; that is, the independent-electron approximation is still in effect.

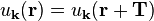

As shown by Bloch's theorem, introducing a periodic potential into the Schrödinger equation results in a wave function of the form

where the function u has the same periodicity as the lattice:

(where T is a lattice translation vector.)

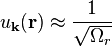

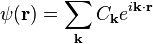

Because it is a nearly free electron approximation we can assume that

A solution of this form can be plugged into the Schrödinger equation, resulting in the central equation:

where the kinetic energy  is given by

is given by

which, after dividing by  , reduces to

, reduces to

if we assume that  is almost constant and

is almost constant and

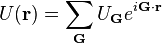

The reciprocal parameters Ck and UG are the Fourier coefficients of the wave function ψ(r) and the screened potential energy U(r), respectively:

The vectors G are the reciprocal lattice vectors, and the discrete values of k are determined by the boundary conditions of the lattice under consideration.

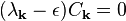

In any perturbation analysis, one must consider the base case to which the perturbation is applied. Here, the base case is with U(x) = 0, and therefore all the Fourier coefficients of the potential are also zero. In this case the central equation reduces to the form

This identity means that for each k, one of the two following cases must hold:

,

,

If the values of  are non-degenerate, then the second case occurs for only one value of k, while for the rest, the Fourier expansion coefficient

are non-degenerate, then the second case occurs for only one value of k, while for the rest, the Fourier expansion coefficient  must be zero. In this non-degenerate case, the standard free electron gas result is retrieved:

must be zero. In this non-degenerate case, the standard free electron gas result is retrieved:

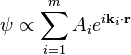

In the degenerate case, however, there will be a set of lattice vectors k1, ..., km with λ1 = ... = λm. When the energy  is equal to this value of λ, there will be m independent plane wave solutions of which any linear combination is also a solution:

is equal to this value of λ, there will be m independent plane wave solutions of which any linear combination is also a solution:

Non-degenerate and degenerate perturbation theory can be applied in these two cases to solve for the Fourier coefficients Ck of the wavefunction (correct to first order in U) and the energy eigenvalue (correct to second order in U). An important result of this derivation is that there is no first-order shift in the energy ε in the case of no degeneracy, while there is in the case of near-degeneracy, implying that the latter case is more important in this analysis. Particularly, at the Brillouin zone boundary (or, equivalently, at any point on a Bragg plane), one finds a twofold energy degeneracy that results in a shift in energy given by:

This energy gap between Brillouin zones is known as the band gap, with a magnitude of  .

.

Results

Introducing this weak perturbation has significant effects on the solution to the Schrödinger equation, most significantly resulting in a band gap between wave vectors in different Brillouin zones.

Justifications

In this model, the assumption is made that the interaction between the conduction electrons and the ion cores can be modeled through the use of a "weak" perturbing potential. This may seem like a severe approximation, for the Coulomb attraction between these two particles of opposite charge can be quite significant at short distances. It can be partially justified, however, by noting two important properties of the quantum mechanical system:

- The force between the ions and the electrons is greatest at very small distances. However, the conduction electrons are not "allowed" to get this close to the ion cores due to the Pauli exclusion principle: the orbitals closest to the ion core are already occupied by the core electrons. Therefore, the conduction electrons never get close enough to the ion cores to feel their full force.

- Furthermore, the core electrons shield the ion charge magnitude "seen" by the conduction electrons. The result is an effective nuclear charge experienced by the conduction electrons which is significantly reduced from the actual nuclear charge.

See also

- Empty Lattice Approximation

- Electronic band structure

- Tight binding model

- Bloch waves

- Kronig-Penney model

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dispersion relations of electrons. |

- Ashcroft, Neil W.; Mermin, N. David (1976). Solid State Physics. Orlando: Harcourt. ISBN 0-03-083993-9.

- Kittel, Charles (1996). Introduction to Solid State Physics (7th ed.). New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-11181-3.

- Elliott, Stephen (1998). The Physics and Chemistry of Solids. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-98194-X.

![\psi_{\bold{k}}(\bold{r}) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\Omega_r}} \left[ \cos(\bold{k}\cdot\bold{r}) + i \sin(\bold{k}\cdot\bold{r})\right]](../I/m/a59b2fde63209f5f42733d616911ea43.png)

![\cos(\bold{k}\cdot\bold{r}) = \frac{1}{2} [ e^{i \bold{k}\cdot\bold{r}} + e^{-i\bold{k}\cdot\bold{r}}]](../I/m/267e09e7844bdaf1ff301ddb44fdfb76.png)

![E = \langle H \rangle =

\int_{\Omega_r}\psi_{\bold{k}}^*(\bold{r})[T + V]\psi_{\bold{k}}(\bold{r}) d\bold{r}](../I/m/0d108bf7b4e47d7358846fc186668f8a.png)

![E_k = \frac{1}{\Omega_r}\int_{\Omega_r} e^{-i\bold{k}\cdot\bold{r}}

\left[\frac{\hbar^2k^2}{2 m} + V(\bold{r})\right]

e^{i\bold{k}\cdot\bold{r}}d\bold{r} =\frac{\hbar^2 k^2}{2 m} + \langle V \rangle](../I/m/d1467809855302bd5072f83210863ea5.png)

![\rho_{\bold{k}}^c(\bold{r}) = \frac{1}{2\Omega} \left[1 + \cos(2 \bold{k}\cdot\bold{r})\right]](../I/m/76f055d5ee8c486035d3b61eca0044ae.png)

![\rho_{\bold{k}}^s(\bold{r}) = \frac{1}{2\Omega} \left[1 - \cos(2 \bold{k}\cdot\bold{r})\right]](../I/m/df199e455e57a2d30fa49d2aab57bcca.png)