Neapolitan chord

In music theory, a Neapolitan chord (or simply a "Neapolitan") is a major chord built on the lowered second (supertonic) scale degree. Also, in Schenkerian analysis, it is known as Phrygian II,[1] since in minor scales the chord is built on the notes of the corresponding Phrygian mode.

Although it is sometimes indicated by an "N" rather than a "♭II".,[2] some analysts prefer the latter because it indicates the relation of this chord to the supertonic.[3] The Neapolitan chord does not fall into the categories of mixture or tonicization. Moreover, even Schenkerians like Carl Schachter do not consider this chord as a sign for a shift to the Phrygian mode.[3] Therefore, like the augmented sixth chords it should be assigned to a separate category of chromatic alteration.

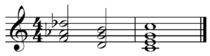

The Neapolitan most commonly occurs in first inversion so that it is notated either as ♭II6 or N6 and normally referred to as a Neapolitan sixth chord.[4] In C, for example, a Neapolitan sixth chord in first inversion contains an interval of a minor sixth between F and D♭.

Origin of the name

Especially in its most common occurrence (as a triad in first inversion), the chord is known as the "Neapolitan sixth":

- The interval between the bass note and the root of the chord is a minor sixth. For example, in the key of C major or C minor the chord consists of D♭ (the root note), F (the third of the triad), and A♭ (the fifth of the triad) – with the F in the bass, to make it a ♭II6 or N6 rather than a root-position ♭II. The interval of a minor sixth is between F and D♭.

- The chord is called "Neapolitan" because it is associated with the Neapolitan School, which included Alessandro Scarlatti, Pergolesi, Paisiello, Cimarosa, and other important 18th-century composers of Italian opera; but it seems already to have been an established, if infrequent, harmonic practice by the end of the 17th century, used by Carissimi, Corelli, and Purcell. It was also a favorite idiom among composers in the Classical period, especially Beethoven, who extended its use in root-position and second-inversion chords also (examples include the opening of the String Quartet op. 95, the third movement of the Hammerklavier Sonata, and the first movement, appearing four times, of the Moonlight Sonata).[5]

Harmonic function

|

IV-V-I progression without Neapolitan

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

In tonal harmony, the function of the Neapolitan chord is to prepare the dominant, substituting for the IV or ii (particularly ii6) chord. For example, it often precedes an authentic cadence, where it functions as a subdominant (IV). In such circumstances, the Neapolitan sixth is a chromatic alteration of the subdominant, and it has an immediately recognizable and poignant sound.

For example, in C major, the IV (subdominant) triad in root position contains the notes F, A, and C. By lowering the A by a semitone to A♭ and raising the C by a semitone to D♭, the Neapolitan sixth chord F-A♭-D♭ is formed. In C minor, the resemblance between the subdominant (F-A♭-C) and the Neapolitan (F-A♭-D♭) is even stronger, since only one note differs by a half-step. (The Neapolitan is also only a half-step away from the diminished supertonic triad in minor in first inversion, F-A♭-D, and thus lies chromatically between the two primary subdominant function chords.)

-I

-I  |

♭II6-V-I

♭II6-V-I |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The Neapolitan sixth chord is particularly common in minor keys. As a simple alteration of the subdominant triad (iv) of the minor mode, it provides contrast as a major chord compared to the minor subdominant or the diminished supertonic triad. The most common variation on the Neapolitan chord is the Neapolitan major seventh, which adds a major seventh to the chord (this also happens to be the tonic).

Further harmonic contexts

A common use of the Neapolitan chord is in tonicizations and modulations to different keys. It is the most common means of modulating down a semitone, which is usually done by using the I chord in a major key as a Neapolitan chord (or a flatted major supertonic chord in the new key, a semitone below the original).

Occasionally, a minor 7th or augmented 6th is added to the Neapolitan chord, which turns it into a potential secondary dominant that can allow tonicization or modulation to the ♭V/♯IV key area relative to the primary tonic. Whether the added note were notated as a minor 7th or augmented 6th largely depends on how the chord resolves. For example, in C major or C minor, the Neapolitan chord with an augmented 6th (B-natural added to D♭ major chord) very likely resolves in C major or minor, or possibly into some other closely related key such as F minor.

However, if the extra note is considered an added seventh (C♭), this is the best notation if the music is to lead into G♭ major or minor. If the composer chose to lead into F♯ major or minor, very likely the Neapolitan chord would be notated enharmonically based on C♯ (for example: C♯-E♯-G♯-B), although composers vary in their practice on such enharmonic niceties.

Another such use of the Neapolitan is along with the German augmented sixth chord, which can serve as a pivot chord to tonicize the Neapolitan as a tonic.![]() Play In C major/minor, the German augmented sixth chord is an enharmonic A♭7 chord, which could lead as a secondary dominant to D♭, the Neapolitan key area. As the dominant to ♭II, the A♭7 chord can then be respelled as a German augmented sixth, resolving back to the home key of C major/minor.

Play In C major/minor, the German augmented sixth chord is an enharmonic A♭7 chord, which could lead as a secondary dominant to D♭, the Neapolitan key area. As the dominant to ♭II, the A♭7 chord can then be respelled as a German augmented sixth, resolving back to the home key of C major/minor.

Voice leading

Because of its close relationship to the subdominant, the Neapolitan sixth resolves to the dominant using similar voice-leading. In the present example of a C major/minor tonic, the D♭ generally moves down by step to the leading tone B-natural (creating the expressive melodic interval of a diminished third, one of the few places this interval is accepted in traditional voice-leading), while the F in the bass moves up by step to the dominant root G. The fifth of the chord (A♭) usually resolves down a semitone to G as well. In four-part harmony, the bass note F is generally doubled, and this doubled F either resolves down to D or remains as the seventh F of the G-major dominant seventh chord. In summary, the conventional resolution is for all upper voices to move down against a rising bass.

Care must be taken to avoid consecutive fifths when moving from the Neapolitan to the cadential 6

4. The simplest solution is to avoid placing the fifth of the chord in the soprano voice. If the root or (doubled) third is in the soprano voice, all upper parts simply resolve down by step while the bass rises. According to some theorists, however, such an unusual consecutive fifth (with both parts descending a semitone) is allowable in chromatic harmony, so long as it does not involve the bass voice. (The same allowance is often made more explicitly for the German augmented sixth, except in that case it may involve the bass – or must, if the chord is in its usual root position.)

Inversions

The flatted major supertonic chord is sometimes used in root position (in which case there may be even more concessions regarding consecutive fifths, similar to those just discussed). The use of a root position Neapolitan chord may be appealing to composers who wish for the chord to resolve outwards to the dominant in first inversion; the flatted supertonic moves to the leading tone and the flatted submediant may move down to the dominant or up to the leading tone. Although the flatted submediant moves similarly to the flatted supertonic, the transition from a root position Neapolitan chord to a first inversion dominant has more outward motion than the first inversion, whose notes all move towards tonic.

An example of a flatted major supertonic chord occurs in the second to last bar of Chopin's Prelude in C minor, Op. 28, No. 20. In very rare cases, the chord occurs in second inversion; for example, in Handel's Messiah, in the aria Rejoice greatly.[6]

In popular music

In rock and popular music, examples of its use, notated as N and without "traditional functional connotations," include:

- Alexander Rybak's and Paula Seling's "I'll Show You"[7]

- The Beatles' "Do You Want to Know a Secret"[8]

- The Beatles' "I am the Walrus" (Although the Em chord does not appear in the song, the transition F-B-C is clearly N-V-VI of the Em key.)

- Beyonce's "Haunted"[9]

- Fleetwood Mac's "Save Me"[10]

- Journey's "Who's Crying Now"[11]

- Katy Perry's "Choose Your Battles"[12]

- Stefani Germanotta and Anton Zaslavski's "G.U.Y", recorded by Lady Gaga (Neapolitan major seventh in bar 3)[13]

- Lionel Richie's "Hello"[14]

- Michele Perniola and Anita Simoncini's "Chain of Lights"[15]

- The Moody Blues' "Nights in White Satin"[16]

- Livin' Joy's "Don't Stop Movin'"[17]

- Radiohead's "Karma Police"[18]

- Robin Thicke's "Fall Again"[19]

- The Rolling Stones' "Mother's Little Helper"[20]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Oswald Jonas (1982). Introduction to the Theory of Heinrich Schenker (1934: Das Wesen des musikalischen Kunstwerks: Eine Einführung in Die Lehre Heinrich Schenkers), Translated by John Rothgeb.: p.29n29. ISBN 0-582-28227-6.

- ↑ Clendinning, Jane Piper (2010). The Musician's Guide to Theory and Analysis. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0393930815.

- 1 2 Aldwell, Edward; Schachter, Carl (2003). Harmony and Voice Leading (3 ed.). Australia, United States: Thomson/Schirmer. pp. 490–491. ISBN 0-15-506242-5. OCLC 50654542.

- ↑ Bartlette, Christopher, and Steven G. Laitz (2010). Graduate Review of Tonal Theory. New York: Oxford University Press, pg 184. ISBN 978-0-19-537698-2

- ↑ William Drabkin. "Neapolitan sixth chord". In Macy, Laura. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

- ↑ Christ, William (1973), Materials and Structure of Music 2 (2 ed.), Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, pp. 146–7, ISBN 0-13-560342-0, OCLC 257117 LCC MT6 M347 1972

- ↑ Blatter, Alfred (2012). Revisiting Music Theory: A Guide to the Practice

- ↑ Walter Everett. The Beatles as Musicians:Revolver Through the Anthology. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 310. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ Wass, Mike (December 13, 2013). "Beyonce's 'Beyonce': Track-By-Track Album Review". Idolator. Spin Media. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ "Musicnotes.com: Unsupported Browser or Operating System". musicnotes.com. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "Musicnotes.com: Unsupported Browser or Operating System". musicnotes.com. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "Musicnotes.com: Unsupported Browser or Operating System". musicnotes.com. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "G.U.Y. by Lady Gaga: Digital Sheet Music". musicnotes.com. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "Unsupported Browser or Operating System". Musicnotes.com. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- ↑ S, Sopon (17 December 2014). "Michele Perniola and Anita Simoncini: The Peppermints are far from over". wiwibloggs. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ↑ Stephenson, Ken (2002). What to Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis, pp.39, 89. ISBN 978-0-300-09239-4.

- ↑ Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- ↑ "Musicnotes.com: Unsupported Browser or Operating System". musicnotes.com. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ Halstead, Craig; Cadman, Chris (2007). Michael Jackson: For The Record. Bedfordshire: Authors OnLine Ltd. p. 107. ISBN 0-7552-0267-8.

- ↑ Stephenson, Ken (2002). What to Listen for in Rock: A Stylistic Analysis, p.90. ISBN 978-0-300-09239-4.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||