Attenuation

In physics, attenuation (in some contexts also called extinction) is the gradual loss in intensity of any kind of flux through a medium. For instance, dark glasses attenuate sunlight, lead attenuates X-rays, and water attenuates both light and sound.

In electrical engineering and telecommunications, attenuation affects the propagation of waves and signals in electrical circuits, in optical fibers, and in air (radio waves). Electrical attenuators and optical attenuators are common manufactured components in this field.

Background

In many cases, attenuation is an exponential function of the path length through the medium. In chemical spectroscopy, this is known as the Beer–Lambert law. In engineering, attenuation is usually measured in units of decibels per unit length of medium (dB/cm, dB/km, etc.) and is represented by the attenuation coefficient of the medium in question.[1] Attenuation also occurs in earthquakes; when the seismic waves move farther away from the epicenter, they grow smaller as they are attenuated by the ground.

Ultrasound

One area of research in which attenuation figures strongly is in ultrasound physics. Attenuation in ultrasound is the reduction in amplitude of the ultrasound beam as a function of distance through the imaging medium. Accounting for attenuation effects in ultrasound is important because a reduced signal amplitude can affect the quality of the image produced. By knowing the attenuation that an ultrasound beam experiences traveling through a medium, one can adjust the input signal amplitude to compensate for any loss of energy at the desired imaging depth.[2]

- Ultrasound attenuation measurement in heterogeneous systems, like emulsions or colloids, yields information on particle size distribution. There is an ISO standard on this technique.[3]

- Ultrasound attenuation can be used for extensional rheology measurement. There are acoustic rheometers that employ Stokes' law for measuring extensional viscosity and volume viscosity.

Wave equations which take acoustic attenuation into account can be written on a fractional derivative form, see the article on acoustic attenuation or e.g. the survey paper.[4]

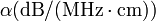

Attenuation coefficient

Attenuation coefficients are used to quantify different media according to how strongly the transmitted ultrasound amplitude decreases as a function of frequency. The attenuation coefficient ( ) can be used to determine total attenuation in dB in the medium using the following formula:

) can be used to determine total attenuation in dB in the medium using the following formula:

As this equation shows, besides the medium length and attenuation coefficient, attenuation is also linearly dependent on the frequency of the incident ultrasound beam. Attenuation coefficients vary widely for different media. In biomedical ultrasound imaging however, biological materials and water are the most commonly used media. The attenuation coefficients of common biological materials at a frequency of 1 MHz are listed below:[5]

| Material |  |

|---|---|

| Air | 1.64 (20°C)[6] |

| Blood | 0.2 |

| Bone, cortical | 6.9 |

| Bone, trabecular | 9.94 |

| Brain | 0.6 |

| Breast | 0.75 |

| Cardiac | 0.52 |

| Connective tissue | 1.57 |

| Dentin | 80 |

| Enamel | 120 |

| Fat | 0.48 |

| Liver | 0.5 |

| Marrow | 0.5 |

| Muscle | 1.09 |

| Tendon | 4.7 |

| Soft tissue (average) | 0.54 |

| Water | 0.0022 |

There are two general ways of acoustic energy losses: absorption and scattering, for instance light scattering.[7] Ultrasound propagation through homogeneous media is associated only with absorption and can be characterized with absorption coefficient only. Propagation through heterogeneous media requires taking into account scattering.[8] Fractional derivative wave equations can be applied for modeling of lossy acoustical wave propagation, see also acoustic attenuation and Ref.[4]

Light attenuation in water

Shortwave radiation emitted from the sun have wavelengths in the visible spectrum of light that range from 360 nm (violet) to 750 nm (red). When the sun’s radiation reaches the sea-surface, the shortwave radiation is attenuated by the water, and the intensity of light decreases exponentially with water depth. The intensity of light at depth can be calculated using the Beer-Lambert Law.

In clear open waters, visible light is absorbed at the longest wavelengths first. Thus, red, orange, and yellow wavelengths are absorbed at higher water depths, and blue and violet wavelengths reach the deepest in the water column. Because the blue and violet wavelengths are absorbed last compared to the other wavelengths, open ocean waters appear deep-blue to the eye.

In near-shore (coastal) waters, sea water contains more phytoplankton than the very clear central ocean waters. Chlorophyll-a pigments in the phytoplankton absorb light, and the plants themselves scatter light, making coastal waters less clear than open waters. Chlorophyll-a absorbs light most strongly in the shortest wavelengths (blue and violet) of the visible spectrum. In near-shore waters where there are high concentrations of phytoplankton, the green wavelength reaches the deepest in the water column and the color of water to an observer appears green-blue or green.

Earthquake

The energy with which an earthquake affects a location depends on the running distance. The attenuation in the signal of ground motion intensity plays an important role in the assessment of possible strong groundshaking. A seismic wave loses energy as it propagates through the earth (attenuation). This phenomenon is tied in to the dispersion of the seismic energy with the distance. There are two types of dissipated energy:

- geometric dispersion caused by distribution of the seismic energy to greater volumes

- dispersion as heat, also called intrinsic attenuation or anelastic attenuation.

Electromagnetic

Attenuation decreases the intensity of electromagnetic radiation due to absorption or scattering of photons. Attenuation does not include the decrease in intensity due to inverse-square law geometric spreading. Therefore, calculation of the total change in intensity involves both the inverse-square law and an estimation of attenuation over the path.

The primary causes of attenuation in matter are the photoelectric effect, compton scattering, and, for photon energies of above 1.022 MeV, pair production.

Radiography

Optics

Attenuation in fiber optics, also known as transmission loss, is the reduction in intensity of the light beam (or signal) with respect to distance travelled through a transmission medium. Attenuation coefficients in fiber optics usually use units of dB/km through the medium due to the relatively high quality of transparency of modern optical transmission media. The medium is typically a fiber of silica glass that confines the incident light beam to the inside. Attenuation is an important factor limiting the transmission of a digital signal across large distances. Thus, much research has gone into both limiting the attenuation and maximizing the amplification of the optical signal. Empirical research has shown that attenuation in optical fiber is caused primarily by both scattering and absorption.

[9] Attenuation in fiber optics can be quantified using the following equation:[10]

Light scattering

The propagation of light through the core of an optical fiber is based on total internal reflection of the lightwave. Rough and irregular surfaces, even at the molecular level of the glass, can cause light rays to be reflected in many random directions. This type of reflection is referred to as "diffuse reflection", and it is typically characterized by wide variety of reflection angles. Most objects that can be seen with the naked eye are visible due to diffuse reflection. Another term commonly used for this type of reflection is "light scattering". Light scattering from the surfaces of objects is our primary mechanism of physical observation. [11] [12] Light scattering from many common surfaces can be modelled by lambertian reflectance.

Light scattering depends on the wavelength of the light being scattered. Thus, limits to spatial scales of visibility arise, depending on the frequency of the incident lightwave and the physical dimension (or spatial scale) of the scattering center, which is typically in the form of some specific microstructural feature. For example, since visible light has a wavelength scale on the order of one micrometer (one millionth of a meter), scattering centers will have dimensions on a similar spatial scale.

Thus, attenuation results from the incoherent scattering of light at internal surfaces and interfaces. In (poly)crystalline materials such as metals and ceramics, in addition to pores, most of the internal surfaces or interfaces are in the form of grain boundaries that separate tiny regions of crystalline order. It has recently been shown that, when the size of the scattering center (or grain boundary) is reduced below the size of the wavelength of the light being scattered, the scattering no longer occurs to any significant extent. This phenomenon has given rise to the production of transparent ceramic materials.

Likewise, the scattering of light in optical quality glass fiber is caused by molecular-level irregularities (compositional fluctuations) in the glass structure. Indeed, one emerging school of thought is that a glass is simply the limiting case of a polycrystalline solid. Within this framework, "domains" exhibiting various degrees of short-range order become the building-blocks of both metals and alloys, as well as glasses and ceramics. Distributed both between and within these domains are microstructural defects that will provide the most ideal locations for the occurrence of light scattering. This same phenomenon is seen as one of the limiting factors in the transparency of IR missile domes.[13]

UV-Vis-IR absorption

In addition to light scattering, attenuation or signal loss can also occur due to selective absorption of specific wavelengths, in a manner similar to that responsible for the appearance of color. Primary material considerations include both electrons and molecules as follows:

- At the electronic level, it depends on whether the electron orbitals are spaced (or "quantized") such that they can absorb a quantum of light (or photon) of a specific wavelength or frequency in the ultraviolet (UV) or visible ranges. This is what gives rise to color.

- At the atomic or molecular level, it depends on the frequencies of atomic or molecular vibrations or chemical bonds, how close-packed its atoms or molecules are, and whether or not the atoms or molecules exhibit long-range order. These factors will determine the capacity of the material transmitting longer wavelengths in the infrared (IR), far IR, radio and microwave ranges.

The selective absorption of infrared (IR) light by a particular material occurs because the selected frequency of the light wave matches the frequency (or an integral multiple of the frequency) at which the particles of that material vibrate. Since different atoms and molecules have different natural frequencies of vibration, they will selectively absorb different frequencies (or portions of the spectrum) of infrared (IR) light.

Applications

In optical fibers, attenuation is the rate at which the signal light decreases in intensity. For this reason, glass fiber (which has a low attenuation) is used for long-distance fiber optic cables; plastic fiber has a higher attenuation and, hence, shorter range. There also exist optical attenuators that decrease the signal in a fiber optic cable intentionally.

Attenuation of light is also important in physical oceanography. This same effect is an important consideration in weather radar, as raindrops absorb a part of the emitted beam that is more or less significant, depending on the wavelength used.

Due to the damaging effects of high-energy photons, it is necessary to know how much energy is deposited in tissue during diagnostic treatments involving such radiation. In addition, gamma radiation is used in cancer treatments where it is important to know how much energy will be deposited in healthy and in tumorous tissue.

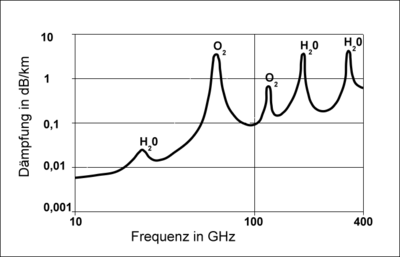

Radio

Attenuation is an important consideration in the modern world of wireless telecommunication. Attenuation limits the range of radio signals and is affected by the materials a signal must travel through (e.g., air, wood, concrete, rain). See the article on path loss for more information on signal loss in wireless communication.

See also

References

- ↑ Essentials of Ultrasound Physics, James A. Zagzebski, Mosby Inc., 1996.

- ↑ Diagnostic Ultrasound, Stewart C. Bushong and Benjamin R. Archer, Mosby Inc., 1991.

- ↑ ISO 20998-1:2006 "Measurement and characterization of particles by acoustic methods"

- 1 2 S. P. Näsholm and S. Holm, "On a Fractional Zener Elastic Wave Equation," Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. Vol. 16, No 1 (2013), pp. 26-50, DOI: 10.2478/s13540-013--0003-1 Link to e-print

- ↑ Culjat, Martin O.; Goldenberg, David; Tewari, Priyamvada; Singh, Rahul S. (2010). "A Review of Tissue Substitutes for Ultrasound Imaging". Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 36 (6): 861–873. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.02.012. PMID 20510184.

- ↑ http://www.ndt.net/article/ultragarsas/63-2008-no.1_03-jakevicius.pdf

- ↑ Bohren,C. F. and Huffman, D.R. "Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles", Wiley, (1983), isbn= 0-471-29340-7

- ↑ Dukhin, A.S. and Goetz, P.J. "Ultrasound for characterizing colloids", Elsevier, 2002

- ↑ Telecommunications: A Boost for Fibre Optics, Z. Valy Vardeny, Nature 416, 489–491, 2002.

- ↑ "Fibre Optics". Bell College. Archived from the original on 2006-02-24.

- ↑ Kerker, M. (1909). "The Scattering of Light (Academic, New York)".

- ↑ Mandelstam, L.I. (1926). "Light Scattering by Inhomogeneous Media". Zh. Russ. Fiz-Khim. Ova. 58: 381.

- ↑ Archibald, P.S. and Bennett, H.E., "Scattering from infrared missile domes", Opt. Engr., Vol. 17, p.647 (1978)

External links

- NIST's XAAMDI: X-Ray Attenuation and Absorption for Materials of Dosimetric Interest Database

- NIST's XCOM: Photon Cross Sections Database

- NIST's FAST: Attenuation and Scattering Tables

- Underwater Radio Communication

![\text{Attenuation} = \alpha [\text{dB}/(\text{MHz} \cdot \text{cm})] \cdot \ell [\text{cm}] \cdot \text{f}[\text{MHz}]](../I/m/a3b053665730627575def7b7afb2aef0.png)