National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005

| National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 | |

|---|---|

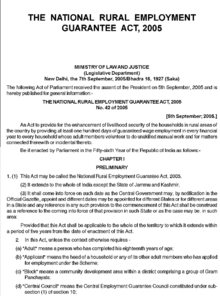

First page of Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act | |

| Status: In force |

| National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 | |

|---|---|

| Country | India |

| Prime Minister | Manmohan Singh |

| Launched | 2 Feb 2006 |

National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 (or, NREGA No 42) was later renamed as the "Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act" (or, MGNREGA), is an Indian labour law and social security measure that aims to guarantee the 'right to work'. It aims to enhance livelihood security in rural areas by providing at least 100 days of wage employment in a financial year to every household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work.[1][2]

Starting from 200 districts on 2 February 2006, the NREGA covered all the districts of India from 1 April 2008.[3] The statute is hailed by the government as "the largest and most ambitious social security and public works programme in the world".[4] In its World Development Report 2014, the World Bank termed it a "stellar example of rural development".[5]

The MGNREGA was initiated with the objective of "enhancing livelihood security in rural areas by providing at least 100 days of guaranteed wage employment in a financial year, to every household whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work".[6] Another aim of MGNREGA is to create durable assets (such as roads, canals, ponds, wells). Employment is to be provided within 5 km of an applicant's residence, and minimum wages are to be paid. If work is not provided within 15 days of applying, applicants are entitled to an unemployment allowance. Thus, employment under MGNREGA is a legal entitlement.

MGNREGA is to be implemented mainly by gram panchayats (GPs). The involvement of contractors is banned. Labour-intensive tasks like creating infrastructure for water harvesting, drought relief and flood control are preferred.

Apart from providing economic security and creating rural assets, NREGA can help in protecting the environment, empowering rural women, reducing rural-urban migration and fostering social equity, among others."[7]

The law provides many safeguards to promote its effective management and implementation. The act explicitly mentions the principles and agencies for implementation, list of allowed works, financing pattern, monitoring and evaluation, and most importantly the detailed measures to ensure transparency and accountability.

Past Scenario

History

Using public employment as a social security measure and for poverty alleviation measure in rural areas has a long history in India. After three decades of experimentation, the government launched major schemes like Jawahar Rozgar Yojana, Employment Assurance Scheme, Food for Work Programme, Jawahar Gram Samridhi Yojana and Sampoorna Grameen Rozgar Yojana that were forerunners to Mahatma Gandhi NREGA. Unlike its precursors, the Mahatma Gandhi NREGA guaranteed employment as a legal right.

Maharashtra was the first state to enact an employment guarantee act in the 1970s. Former Maharashtra Chief Minister late Vasantrao Naik, launched the revolutionary Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme which proved to be a boon for millions of farmers ravaged by two ferocious famines.

The Planning Commission later approved the scheme and the same was adopted on national scale.[8] The relief measures undertaken by the Government of Maharashtra included employment, programmes aimed at creating productive assets such as tree plantation, conservation of soil, excavation of canals, and building artificial lentic water bodies.

Starting from 1960, the first 30 years of experimentation with employment schemes in rural areas taught few important lessons to the government like the ‘Rural Manpower Programme’ taught the lesson of financial management, the ‘Crash Scheme for Rural Employment’ of planning for outcomes, a ‘Pilot Intensive Rural Employment Programme’ of labour-intensive works, the ‘Drought Prone Area Programme’ of integrated rural development, ‘Marginal Farmers and Agricultural Labourers Scheme’ of rural economic development, the ‘Food for Work Programme’ (FWP) of holistic development and better coordination with the states, the ‘National Rural Employment Programme’ (NREP) of community development, and the ‘Rural Landless Employment Guarantee Programme’ of focus on landless households.[9] the government had been merging old schemes to introduce new ones while retaining the basic objective of providing additional wage employment involving unskilled manual work, creating ‘durable’ assets, and improving food security in rural areas through public works with special safeguards for the weaker sections and women of the community.

In later years, major employment schemes like Jawahar Rozgar Yojana (JRY) in 1977, National Rural Employment Programme (NREP) in 1980, Employment Assurance Scheme (EAS), Food for Work Programme (NFFWP) in 2004, Jawahar Gram Samridhi Yojana (JGSY) and Sampoorna Grameen Rozgar Yojana (SGRY) were launched. Some of them (e.g. NFFWP) provided foodgrains to complement wages.

On 1 April 1989, to converge employment generation, infrastructure development and food security in rural areas, the government integrated NREP and RLEGP[n 1] into a new scheme JRY. The most significant change was the decentralization of implementation by involving local people through PRIs and hence a decreasing role of bureaucracy.[11]

On 2 October 1993, the Employment Assurance Scheme (EAS) was initiated to provide employment during the lean agricultural season. The role of PRIs was reinforced with the local self-government at the district level called the ‘Zilla Parishad’ as the main implementing authority. Later, EAS was merged with SGRY in 2001.[12]

On 1 April 1999, the JRY was revamped and renamed to JGSY with a similar objective. The role of PRIs was further reinforced with the local self-government at the village level called the ‘Village Panchayats’ as the sole implementing authority. In 2001, it was merged with SGRY.[13][14]

In January 2001, the government introduced FWP similar to the one initiated in 1977. Once NREGA was enacted, the two were merged in 2006.[15]

On 25 September 2001 to converge employment generation, infrastructure development and food security in rural areas, the government integrated EAS and JGSY into a new scheme SGRY. The role of PRIs was retained with the ‘Village Panchayats’ as the sole implementing authority.[16] Yet again due to implementation issues, it was merged with Mahatma Gandhi NREGA in 2006.[17]

The total government allocation to these precursors of Mahatma Gandhi NREGA had been about three-quarters of ₹1 trillion (US$15 billion).[18]

Overview

| According to the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007–12), the number of Indians living on less than $1 a day, called Below Poverty Line (BPL), was 300 million that barely declined over the last three decades ranging from 1973 to 2004, although their proportion in the total population decreased from 36 per cent (1993–94) to 28 percent (2004–05),[19] and the rural working class dependent on agriculture was unemployed for nearly 3 months per year.[20] The plan targeted poverty through MGNREGA which promised employment as an entitlement.

Financial allocations for the NREGA increased steadily between 2006-2010 when it touched nearly Rs. 40,000 crores. Since then, however, allocation for NREGA has stagnated just below Rs. 40,000 crores. In 2014-15, allocations were cut dramatically to less than Rs. 30,000 crores. The UPA Government had planned to increase the number of working days from 100 to 150 before the 2014 Lok Sabha Elections in the country but failed.[21] |

The NDA government has decided to provide 150 days for rain hit areas.[22]

The law on paper

Details of the law

The Act is to be implemented by the State Government, with funding from the Central Government. According to Section 13, the "principal authorities" for planning and implementation of the Scheme are the Panchayats at the District, Intermediate and village levels. However, the division of responsibilities between different authorities is actually quite complex.

The basic unit of implementation is the Block. In each Block, a "Programme Officer" will be in charge. The Programme Officer is supposed to be an officer of rank no less than the Block Development Officer (BDO), paid by the Central Government, and with the implementation of NREGA as his or her sole responsibility. The Programme Officer is accountable to the "Intermediate Panchayat" as well as to the District Coordinator.

Implementing agencies include any agency that is "authorized by the Central Government or the State Government to undertake the implementation of any work" taken up under NREGA [Section 2(g)]. The main implementing agencies are the Gram Panchayats: at least 50 per cent of the works (in terms of share of the NREGA funds) have to be implemented through the Gram Panchayats [Section 16(5)]. Other implementing agencies include the Panchayat Samiti, the District Panchayats, and "line departments" such as the Public Works Department, the Forest Department, the Irrigation Department, and so on. NREGA also allows NGOs to act as implementing agencies. Even the works of implementing agencies other than the Gram Panchayat must be presented before the gram sabha and included in the annual shelf of works.

The registration process involves an application to the Gram Panchayat and issue of job cards. The wage employment must be provided within 15 days of the date of application. The work entitlement of ‘100 days per household per year’ may be shared between different adult members of the same household.[23]

The law also lists permissible works: water conservation and water harvesting; drought proofing including afforestation; irrigation works; restoration of traditional water bodies; land development; flood control; rural connectivity; and works notified by the government. The Act sets a minimum limit to the wage-material ratio as 60:40. The provision of accredited engineers, worksite facilities and a weekly report on worksites is also mandated by the Act.[24]

Furthermore, the Act sets a minimum limit to the wages, to be paid with gender equality, either on a time-rate basis or on a piece-rate basis. The states are required to evolve a set of norms for the measurement of works and schedule of rates. unemployment allowance must be paid if the work is not provided within the statutory limit of 15 days.[25]

The law stipulates Gram Panchayats to have a single bank account for NREGA works which shall be subjected to public scrutiny. To promote transparency and accountability, the act mandates ‘monthly squaring of accounts’.[26] To ensure public accountability through public vigilance, the NREGA designates ‘social audits’ as key to its implementation.[27]

The most detailed part of the Act (chapter 10 and 11) deals with transparency and accountability that lays out role of the state, the public vigilance and, above all, the social audits.[28]

For evaluation of outcomes, the law also requires management of data and maintenance of records, like registers related to employment, job cards, assets, muster rolls and complaints, by the implementing agencies at the village, block and state level.[29]

The legislation specifies the role of the state in ensuring transparency and accountability through upholding the right to information and disclosing information proactively, preparation of annual reports by CEGC for Parliament and SEGCs for state legislatures, undertaking mandatory financial audit by each district along with physical audit, taking action on audit reports, developing a Citizen's Charter, establishing vigilance and monitoring committees, and developing grievance redressal system.[30]

The Act recommends establishment of ‘Technical Resource Support Groups’ at district, state and central level and active use of Information Technology, like creation of a ‘Monitoring and Information System (MIS)’ and a NREGA website, to assure quality in implementation of NREGA through technical support.[31]

The law allows convergence of NREGA with other programmes. As NREGA intends to create ‘additional’ employment, the convergence should not affect employment provided by other programmes.[32]

The law and the Constitution of India

The Constitution of India – India's fundamental and supreme law. The Act aims to follow the Directive Principles of State Policy enunciated in Part IV of the Constitution of India. The law by providing a 'right to work' is consistent with Article 41 that directs the State to secure to all citizens the right to work.[33] The statute also seeks to protect the environment through rural works[34] which is consistent with Article 48A that directs the State to protect the environment.[35] In accordance with the Article 21 of the Constitution of India that guarantees the right to life with dignity to every citizen of India, this act imparts dignity to the rural people through an assurance of livelihood security.[36] The Fundamental Right enshrined in Article 16 of the Constitution of India guarantees equality of opportunity in matters of public employment and prevents the State from discriminating against anyone in matters of employment on the grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex, descent, place of birth, place of residence or any of them.[37] NREGA also follows Article 46 that requires the State to promote the interests of and work for the economic uplift of the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes and protect them from discrimination and exploitation.[38] Article 40 mandates the State to organise village panchayats and endow them with such powers and authority as may be necessary to enable them to function as units of self-government.[39] Conferring the primary responsibility of implementation on Gram Panchayats, the Act adheres to this constitutional principle. Also the process of decentralization initiated by 73rd Amendment to the Constitution of India that granted a constitutional status to the Panchayats[40] is further reinforced by the Mahatma Gandhi NREGA that endowed these rural self-government institutions with authority to implement the law.[41] |

The law in action

Independent Academic Research

Academic research has focused on many dimensions of the NREGA: economic security, self-targeting, women's empowerment, asset creation, corruption, how the scheme impacts agricultural wages. An early overall assessment in the north India states suggested that NREGA was "making a difference to the lives of the rural poor, slowly but surely." [42]

The evidence on self-targeting suggests that works though there is a lot of unmet demand for work.[43][44]

One of the objectives of NREGA was to improve the bargaining power of labour who often faced exploitative market conditions. Several studies have found that agricultural wages have increased significantly, especially for women since the inception of the scheme.[45][46] This indicates that overall wage levels have increased due to the act, however, further research highlights that the key benefit of the scheme lies in the reduction of wage volatility.[47] This highlights that NREGA may be an effective insurance scheme. Ongoing research efforts try to evaluate the overall welfare effects of the scheme; a particular focus has been to understand whether the scheme has reduced migration into urban centers for casual work.

Another important aspect of NREGA is the potential for women's empowerment by providing them opportunities for paid work. One third of all employment is reserved for women, there is a provision for equal wages to men and women, provision for child care facilities at the worksite - these are three important provisions for women in the Act.[48] More recent studies have suggested that women's participation has remained high, though there are inter-state variations.[49] One study in border villages of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat studied the effect on short term migration and child welfare.[50] and finds that among children who do not migrate, grade completed is higher. The same study found that demand for NREGA work is higher, even though migrant wages are higher.[51]

On asset creation, there have not been too many detailed studies. A few focusing on the potential for asset creation under NREGA suggest that (a) the potential is substantial and (b) in some places it is being realized and (c) lack of staff, especially technical staff rather than lack of material are to blame for poor realization of this potential.[52][53] Others have pointed out that water harvesting and soil conservation works promoted through NREGA "could have high positive results on environment security and biodiversity and environment conservation"[54] A study conducted by researchers at the Indian Institute of Science and other collaborators attempts to quantify the environmental and socio-economic benefits of works done through the NREGA [55]

Corruption in government programmes has remained a serious concern, and NREGA has been no exception. According to recent estimates, wage corruption in NREGA has declined from about 50% in 2007-8 to between 4-30% in 2009-10.[56] Much of this improvement is attributable to the move to pay NREGA wages through bank and post office accounts.[57] Some of the success in battling corruption can also be attributed to the strong provisions for community monitoring.[58] Others find that "the overall social audit effects on reducing easy-to-detect malpractices was mostly absent".[59]

A few papers also study the link between electoral gains and implementation of NREGA. One studies the effect in Andhra Pradesh - the authors find that "while politics may influence programme expenditure in some places and to a small extent, this is not universally true and does not undermine the effective targeting and good work of the scheme at large." [60] The two other studies focus on these links in Rajasthan [61] and West Bengal.[62]

Assessment of the act by the constitutional auditor

The second performance audit by the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India covered 3,848 gram panchayats (GPs) in 28 states and 4 union territories (UTs) from April 2007 to March 2012.[63] This comprehensive survey by the CAG documents lapses in implementation of the act.[64][65]

The main problems identified in the audit included: a fall in the level of employment, low rates of completion of works (only 30 per cent of planned works had been completed), poor planning (in one-third of Gram Panchayats, the planning process mandated by the act had not been followed), lack of public awareness partly due to poor information,[66] education and communication IEC) by the state governments, shortage of staff (e.g., Gram Rozgar Sewaks had not been appointed in some states) and so on.[67] Notwithstanding the statutory requirement of notification, yet five states had not even notified the eight-years-old scheme.

The comprehensive assessment of the performance of the law by the constitutional auditor revealed serious lapses arising mainly due to lack of public awareness, mismanagement and institutional incapacity. The CAG also suggested some corrective measures.

Even though the mass social audits have a statutory mandate of Section 17 (as outlined in Chapter 11 of the NREGA Operational Guidelines), only seven states have the institutional capacity to facilitate the social audits as per prescribed norms.[68] Although the Central Council is mandated to establish a central evaluation and monitoring system as per the NREGA Operational Guidelines, even after six years it is yet to fulfill the NREGA directive. Further, the CAG audit reports discrepancies in the maintenance of prescribed basic records in up to half of the gram panchayats (GPs) which inhibits the critical evaluation of the NREGA outcomes. The unreliability of Management Information System (MIS), due to significant disparity between the data in the MIS and the actual official documents, is also reported.[69]

To increase public awareness, the intensification of the Information, Education and Communication (IEC) activities is recommended. To improve management of outcomes, it recommended proper maintenance of records at the gram panchayat (GP) level. Further the Central Council is recommended to establish a central evaluation and monitoring system for "a national level, comprehensive and independent evaluation of the scheme". The CAG also recommends a timely payment of unemployment allowance to the rural poor and a wage material ratio of 60:40 in the NREGA works. Moreover, for effective financial management, the CAG recommends proper maintenance of accounts, in a uniform format, on a monthly basis and also enforcing the statutory guidelines to ensure transparency in the disposal of funds. For capacity building, the CAG recommends an increase in staff hiring to fill the large number of vacancies.[70]

For the first time, the CAG also included a survey of more than 38,000 NREGA beneficiaries.[71] An earlier evaluation of the NREGA by the CAG was criticized for its methodology.[72]

Evaluation of the law by the government

Ex-Prime Minister of India Manmohan Singh released an anthologys of research studies on the MGNREGA called "MGNREGA Sameeksha" in New Delhi on 14 July 2012, about a year before the CAG report.[73] Aruna Roy and Nikhil Dey said that "the MGNREGA Sameeksha is a significant innovation to evaluate policy and delivery".[74] The anthology draws on independent assessments of MGNREGA conducted by Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs), Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and others in collaboration with United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) published from 2008 to 2012.[75] The Prime Minister said:

The Mahatma Gandhi NREGA story in numbers is a story worth telling... the scheme scores high on inclusivness...no welfare scheme in recent memory has caught the imagination of the people as much as NREGA has ... under which ₹1,10,000 crore (about USD$25 billion) have been spent to pay wages to 1,200 crore (12 billion) people.[76]

Minister of Rural Development Jairam Ramesh says in the 'MGNREGA Sameeksha':

It is perhaps the largest and most ambitious social security and public works programme in the world. ... soundness and high potential of the MGNREGA are well established ... . That, at any rate, is one of the main messages emerging from this extensive review of research on MGNREGA. It is also a message that comes loud and clear from the resounding popularity of MGNREGA—today, about one-fourth of all rural households participate in the programme every year.[4]

Meanwhile, the social audits in two Indian states highlight the potential of the law if implemented effectively.

Further the Minister says:

MGNREGA’s other quantitative achievements have been striking as well:

- Since its inception in 2006, around ₹1,10,000 crore (about USD$25 billion) has gone directly as wage payment to rural households and 1200 crore (12 billion) person-days of employment has been generated. On an average, 5 crore (50 million) households have been provided employment every year since 2008.

- Eighty per cent of households are being paid directly through bank/post office accounts, and 10 crore (100 million) new bank/post office accounts have been opened.

- The average wage per person-day has gone up by 81 per cent since the Scheme’s inception, with state-level variations. The notified wage today varies from a minimum of ₹122 (USD$2.5) in Bihar, Jharkhand to ₹191 (USD$4) in Haryana.

- Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) have accounted for 51 per cent of the total person-days generated and women for 47 per cent, well above the mandatory 33 per cent as required by the Act.

- 146 lakh (14.6 million) works have been taken up since the beginning of the programme, of which about 60 per cent have been completed.

- 12 crore (120 million) Job Cards (JCs) have been given and these along with the 9 crore (90 million) muster rolls have been uploaded on the Management Information System (MIS), available for public scrutiny. Since 2010–11, all details with regard to the expenditure of the MGNREGA are available on the MIS in the public domain.[77]

Social audit

Main article: Social audit

Civil society organisations (CSOs), nongovernmental organisations (NGOs), political representatives, civil servants and workers of Rajasthan and Andhra Pradesh collectively organise social audits to prevent corruption under the NREGA.[78] As the corruption is attributed to the secrecy in governance, the 'Jansunwai' or public hearing and the right to information (RTI), enacted in 2005, are used to fight this secrecy.[79] Official records obtained using RTI are read out at the public hearing to identify and rectify irregularities. "This process of reviewing official records and determining whether state reported expenditures reflect the actual monies spent on the ground is referred to as a social audit."[80] Participation of informed citizens promotes collective responsibility and awareness about entitlements.[81]  The process of a social audit A continuous process of social audit on NREGA works involves public vigilance and verification at the stipulated 11 stages of implementation: registration of families; distribution of job cards; receipt of work applications; selection of suitable public works; preparation of technical estimates; work allocation; implementation and supervision; payment of wages; payment of unemployment allowance; evaluation of outcomes; and mandatory social audit in the Gram Sabha or Social Audit Forum. The Gram Panchayat Secretary called ‘Sarpanch’ is designated as the authority responsible for carrying out the social audit at all stages. For some stages, the programme officer and the junior engineer is also responsible along with Sarpanch.[82] The statute designates the Gram Sabha meetings held to conduct social audit as the ‘Social Audit Forums’ and spells out three steps to make them effective: publicity and preparation of documents; organizational and procedural aspects; and the mandatory agenda involving questions verifying compliance with norms specified at each of the 11 stages of implementation.[83] An application under the RTI to access relevant official documents is the first step of the social audit. Then the management personnel of the social audit verify these official records by conducting field visits. Finally, the 'Jansunwai' or public hearing is organised at two levels: the Panchayat or village level and the Mandal level. The direct public debate involving the beneficiaries, political representatives, civil servants and, above all, the government officers responsible for implementing the NREGA works highlights corruption like the practice of rigging muster rolls (attendance registers) and also generates public awareness about the scheme.[84] These social audits on NREGA works in Rajasthan highlight: a significant demand for the scheme, less that 2 per cent corruption in the form of fudging of muster rolls, building the water harvesting infrastructure as the first priority in the drought-prone district, reduction of out-migration, and above all the women participation of more than 80 per cent in the employment guarantee scheme. The need for effective management of tasks, timely payment of wages and provision of support facilities at work sites is also emphasised.[85][86] To assess the effectiveness of the mass social audits on NREGA works in Andhra Pradesh, a World Bank study investigated the effect of the social audit on the level of public awareness about NREGA, its effect on the NREGA implementation, and its efficacy as a grievance redressal mechanism. The study found that the public awareness about the NREGA increased from about 30 per cent before the social audit to about 99 per cent after the social audit. Further, the efficacy of NREGA implementation increased from an average of about 60 per cent to about 97 per cent.[87][88] |

Save MGNREGA

'Save MGNREGA' is a set of demands proposed during the joint meeting of the national leadership of CITU, AIAWU, AIDWA and AIKS in New Delhi. The agenda was to discuss the dilution of MGNREGA scheme by the new government. Following demands were proposed:[89]

1. Government of India should increase the Central allocation for the scheme so that number of workdays can be increased to 200 and per day wage can be increased to Rs. 300.

2. Job card to be issued for everyone who demands job, failing which, after 15 days employment benefits should be given.

3. Minimum 100 days of work should be ensured to all card holders

4. Minimum wage act should be strictly implemented. Delay in wage payment should be resolved.

5. MGNREGA should be extended to urban areas.

6. Gram Sabhas should be strengthened to monitor proper implementation of the scheme and also to check corruption.

New Amendments Proposed in 2014

Union Rural development Minister, Nitin Gadkari, proposed to limit MGNREGA programmes within tribal and poor areas. He also proposed to change the labour:material ratio from 60:40 to 51:49. As per the new proposal the programme will be implemented in 2,500 backward blocks coming under Intensive Participatory Planning Exercise. These blocks are identified per the Planning Commission Estimate of 2013 and a Backwardness Index prepared by Planning Commission using 2011 census. This backwardness index consist of following five parameters - percentage of households primarily depended on agriculture, female literacy rates, households without access to electricity, households without access to drinking water and sanitation within the premises and households without access to banking facilities.[90]

Both proposals came in for sharp criticism. A number of economists with diverse views opposed the idea of restricting or "focussing" implementation in a few districts or blocks.[91][92][93]

In the November 2014 cabinet expansion, Birender Singh replaced Nitin Gadkari as rural development minister. Among the first statements made by the new minister was an assurance that NREGA would continue in all districts. Around the same time, however, NREGA budget saw a sharp cut [94] and in the name of 'focusing' on a few blocks the programme has been limited to those blocks.[95]

Controversies

A major criticism of NREGA is that it is making agriculture less profitable. Landholders often oppose it on these grounds. The big farmer’s point of view can be summed up as follows: landless labourers are lazy and they don’t want to work on farms as they can get money without doing anything at NREGA worksites; farmers may have to sell their land, thereby laying foundation for the corporate farming.

The workers points of view can be summed up as: labourers do not get more than Rs. 80 in the private agricultural labour market, there is no farm work for several months; few old age people who are jobless for at least 8 months a year; when farm work is available they go there first; farmers employ only young and strong persons to work in their farms and reject the others and hence many go jobless most of the time.

Corruption

NREGA has been criticised for the leakages and corrupt implementation. It has been alleged that individuals have received benefits and work payments for work that they have not done, or have done only on paper, or are not poor.[96] In 2014-15, only 28% of the payments were made on time to workers. Following the allegations of corruption in the scheme, NDA government ordered a re-evaluation of the scheme in 2015.[2]

See also

- Indian labour law

- Economy of India

- Economic development in India

- Poverty in India

- Midday Meal Scheme

- Public Distribution System

- National Food Security Act, 2013

Notes

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, p. 1

- 1 2 Nationwide review of rural job scheme NREGS ordered by government

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, p. 10

- 1 2 Ministry of Rural Development 2012, p. ix

- ↑ Economic Times, retrieved from http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2013-10-10/news/42902947_1_world-bank-world-development-report-safety-net

- ↑ Comptroller and Auditor General of India 2013, p. i

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, pp. 1–2

- ↑ Mukherjee, Pranab. "President Mukherje pays tribute to former Maharashtra CM Vasantrao Naik". ANI. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ↑ Planning Commission 2001, pp. 12–20

- ↑ Planning Commission 2001, pp. 15

- ↑ Planning Commission 2001, pp. 16,24–27

- ↑ Planning Commission 2001, pp. 17–19

- ↑ Planning Commission 2001, pp. 21–23

- ↑ The Hindu 2001

- ↑ Planning Commission 2001, p. 20

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2002, pp. 1–3

- ↑ The Hindu 2006

- ↑ Centre for Science and Environment 2007, p. 7

- ↑ Planning Commission 2007, pp. 5–9

- ↑ Planning Commission 2007, pp. 17–29

- ↑ "Proposal for 150 days of work under MGNREGA". mgnrega.in. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ↑

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, pp. 14–20

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, pp. 21–25

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, pp. 26–29

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, pp. 30–34

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, pp. 46–61

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, pp. 41–62

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, pp. 38–40

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, pp. 41–45

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, pp. 62–64

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, pp. 65–66

- ↑ Ministry of Law and Justice 2008, p. 22

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, p. 22

- ↑ Ministry of Law and Justice 2008, p. 496

- ↑ Ministry of Law and Justice 2008, p. 482

- ↑ Ministry of Law and Justice 2008, p. 479

- ↑ Ministry of Law and Justice 2008, p. 495

- ↑ Ministry of Law and Justice 2008, p. 494

- ↑ Ministry of Law and Justice 2008, p. 601

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, p. 3

- ↑ Dreze and Khera (2000), Battle for Employment Guarantee, retrieved from http://www.frontline.in/static/html/fl2601/stories/20090116260100400.htm

- ↑ Liu and Barrett (2013), Heterogeneous Pro-Poor Targeting in the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme. Available from http://www.epw.in/special-articles/heterogeneous-pro-poor-targeting-national-rural-employment-guarantee-scheme.html

- ↑ van de Walle, Ravallion, Dutta, Murgai (2012), Does India's Employment Guarantee Scheme Guarantee Employment. Available from http://www.epw.in/special-articles/does-indias-employment-guarantee-scheme-guarantee-employment.html

- ↑ Zimmermann (2012) , L. (2012). Labor market impacts of a large-scale public works program: evidence from the Indian Employment Guarantee Scheme. mimeo. Retrieved from ftp://ftp.iza.org/RePEc/Discussionpaper/dp6858.pdf

- ↑ Berg, E., Bhattacharyya, S., Durgam, R., & Ramachandra, M. (2012). Can Rural Public Works Affect Agricultural Wages? Evidence from India. CSAE Working Paper.

- ↑ Fetzer, T. (2013). Can Workfare Programs Moderate Violence? Evidence from India. mimeo, 1–42. Retrieved from http://www.trfetzer.com/wp-content/uploads/nrega.pdf

- ↑ Khera and Nayak (2009), Women Workers and Perceptions of the NREGA http://www.epw.in/special-articles/women-workers-and-perceptions-national-rural-employment-guarantee-act.html

- ↑ Narayanan and Das (2014), Women's participation and Rationing in NREGA http://www.epw.in/special-articles/women-participation-and-rationing-employment-guarantee-scheme.html

- ↑ Coffey (2013) Children’s welfare and short term migration from rural India", Journal of Development Studies, 49(8)

- ↑ Papp (2012) Papp, J. (2012), ‘Essays on India’s Employment Guarantee.’, Ph. D. thesis, Princeton University.

- ↑ Saving people's livelihoodshttp://www.livemint.com/Opinion/hz2CLtVBL7q45SrIfg1BfL/Saving-peoples-livelihoods.html

- ↑ Evaluation of NREGA wells in Jharkhand http://www.epw.in/commentary/evaluation-nrega-wells-jharkhand.html

- ↑ MGNREGA and Biodiversity http://www.epw.in/commentary/mgnrega-and-biodiversity-conservation.html

- ↑ Agricultural and Livelihood Vulnerability Reduction through the MGNREGA | Economic and Political Weekly

- ↑ Learning from NREGA http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/learning-from-nrega/article6342811.ece

- ↑ Adhikari and Bhatia (2009) http://www.epw.in/insight/nrega-wage-payments-can-we-bank-banks.html

- ↑ Improving the Effectiveness of National Rural Employment Guarantee Act | Economic and Political Weekly

- ↑ Afridi and Iversen http://ideasforindia.in/article.aspx?article_id=262

- ↑ Barrett, Liu, Narayanan and Sheahan (2014) http://ideasforindia.in/article.aspx?article_id=375

- ↑ Effective States » Local funds and political competition: Evidence from the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme in India

- ↑ Das (2014) http://www.themenplattform-ez.de/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/SSRN-id2262533.pdf

- ↑ Comptroller and Auditor General of India 2013

- ↑ See the Executive summary http://saiindia.gov.in/english/home/Our_Products/Audit_Report/Government_Wise/union_audit/recent_reports/union_performance/2013/Civil/Report_6/exe-sum.pdf

- ↑ Shira 2012

- ↑ Comptroller and Auditor General of India 2013, p. vii

- ↑ Comptroller and Auditor General of India 2013, pp. vii–ix

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, p. 46

- ↑ Comptroller and Auditor General of India 2013, p. ix

- ↑ Comptroller and Auditor General of India 2013, pp. ix–x

- ↑ Chapter 13 of the CAG report available online http://saiindia.gov.in/english/home/Our_Products/Audit_Report/Government_Wise/union_audit/recent_reports/union_performance/2013/Civil/Report_6/chap_13.pdf

- ↑ CAG Report on NREGA: Fact and Fication http://www.epw.in/insight/cag-report-nrega-fact-and-fiction.html

- ↑ The Hindu 2012

- ↑ Roy & Dey 2012

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2012, p. 79

- ↑ The Times of India 2012

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2012, pp. ix-xi

- ↑ Dobhal 2011, p. 420

- ↑ Goetz 1999

- ↑ Aiyar 2009, pp. 8–9

- ↑ Chandoke 2007

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, pp. 46–54

- ↑ Ministry of Rural Development 2005, pp. 55–61

- ↑ Aiyar 2009, pp. 12–16

- ↑ Malekar 2006

- ↑ Ghildiyal 2006

- ↑ Pokharel 2008

- ↑ Aiyar 2009

- ↑ Retrieved from 'Peoples Democracy' on 14 September 2014

- ↑ {{url=http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/changes-to-mgnregs-may-cut-into-wages/article6433087.ece|publisher=The Hindu}}

- ↑ Retrieved from 'The Times of India' on 16 November 2014.

- ↑ "MNREGA is unwell" http://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/editorials/mgnrega-is-unwell/

- ↑ "NREGA is in need of reform" http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2014-11-12/news/56025989_1_nrega-jean-dreze-leakages

- ↑ Sharpest-ever fund cut for rural job scheme | Business Standard News

- ↑ Union Government Limits MGNREGA to 69 Taluks - The New Indian Express

- ↑ Bhalla, Surjeet S. (12 December 2014), No proof required: Move from NREGA to cash transfers, The Indian Express

References

- Aiyar, Yamini (2009). "Transparency and Accountability in NREGA – A Case Study of Andhra Pradesh" (PDF). Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- Chandoke (2007). Engaging with Civil Society: The democratic Perspective. Center for Civil Society, London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Comptroller and Auditor General of India (2013). "The Comptroller and Auditor General of India". The Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG). Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - Comptroller and Auditor General of India (2013). "Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India on Performance Audit of Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme". Comptroller and Auditor General of India. Retrieved 5 November 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - Centre for Science and Environment (2007). "The National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) Opportunities and Challenges (DRAFT)" (PDF). Centre for Science and Environment. Retrieved 29 October 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - Dobhal, Harsh (2011). Writings on Human Rights, Law, and Society in India: A Combat Law Anthology : Selections from Combat Law, 2002–2010. Socio Legal Information Cent. p. 420. ISBN 978-81-89479-78-7.

- Dreze, Jean. "Learning From NREGA". Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- Dreze, Jean (2004). "Employment Guarantee as a Social Responsibility". Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- Dutta, Puja. Right to Work? Assessing India's Employment Guarantee Scheme in Bihar. World Bank.

- Goetz, A.M and Jenkins, J (1999). "Accounts and Accountability: Theoretical Implications of the Right to Information Movement in India". 3 20. Third World Quarterly.

- Ghildiyal, Subodh (11 June 2006). "More women opt for rural job scheme in Rajasthan". The Times of India. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- Khera, Reetika (2011). "The Battle for Employment Guarantee". Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014.

- Khera, Reetika (2014). "The Whys and Whats of NREGA". India Spend.

- Novotny, J., Kubelkova, J., Joseph, V. (2013): A multi-dimensional analysis of the impacts of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme: a tale from Tamil Nadu. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 34, 3, 322-341. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/sjtg.12037/full

- The Times of India (2012). "PM directs Planning Commission to address gaps in NREGA". The Times of India. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- The Times of India (2013). "CAG finds holes in enforcing MNREGA". The Times of India. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- The Hindu (2001). "PR Dept. loses Central assistance". The Hindu. Retrieved 29 October 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - The Hindu (2006). "CAG report reveals irregularities in Sampoorna Rozgar Yojana". The Hindu. Retrieved 29 October 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - The Hindu (2012). "Manmohan directs Planning Commission to address gaps in NREGA". The Hindu. Retrieved 21 November 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - Roy, Aruna; Dey, Nikhil (2012). "Much more than a survival scheme". The Hindu. The Hindu. Retrieved 21 November 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - Malekar, Anosh (21 May 2006). "The big hope: Transparency marks the NREGA in Dungarpur". InfoChange News & Features. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- Menon, Sudha (10 January 2008). "Right To Information Act and NREGA: Reflections on Rajasthan". Munich Personal RePEc Archive. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- Ministry of Law and Justice (2008). "Constitution of India" (PDF). "Ministry of Law and Justice", Government of India. Retrieved 5 November 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - Ministry of Rural Development (2002). "Sampoorna Grameen Rozgar Yojana (SGRY) Guidelines" (PDF). "Ministry of Rural Development", Government of India. Retrieved 29 October 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - Ministry of Rural Development (2002). "Sampoorna Grameen Rozgar Yojana (SGRY) Guidelines" (PDF). "Ministry of Rural Development", Government of India. Retrieved 29 October 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - Ministry of Rural Development (2005). "Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (Mahatma Gandhi NREGA)" (PDF). "Ministry of Rural Development", Government of India. Retrieved 5 November 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - Ministry of Rural Development (2005). "The National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 (NREGA) – Operational Guidelines" (PDF). "Ministry of Rural Development", Government of India. Retrieved 5 November 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - Ministry of Rural Development (2012). MGNREGA Sameeksha, An Anthology of Research Studies on the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005, 2006–2012 (PDF). "Ministry of Rural Development", Government of India (New Delhi: Orient BlackSwan). ISBN 978-81-250-4725-4. Retrieved 21 November 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - Pasha, Dr. Bino Paul GD and S M Fahimuddin. Role of ICT in Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). S M Fahimuddin Pasha. p. 59. ISBN 978-81-921475-0-5.

- Planning Commission (2007). "Chapter 4: Employment Perspective and Labour Policy" (PDF). "Planning Commission", Government of India. Retrieved 29 October 2013. External link in

|website=(help) - Shira, Dezan & Associates; Devonshire-Ellis, Chris (31 May 2012). Doing Business in India. Springer. ISBN 978-3-642-27617-0.

- World Bank (2008). "Social Audits: from ignorance to awareness. The AP experience". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- NewsYaps (2009). "NREGA: Effects and Implications". Retrieved 12 March 2014.

External links

- Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA)

- Report of the CAG on Performance Audit of MGNREGA

- MGNREGA Sameeksha, An Anthology of Research Studies on MGNREGA

- Reports of the Planning Commission on NREGA

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||