Greco-Roman mysteries

- See Western esotericism for modern "mystery religions" in Western culture

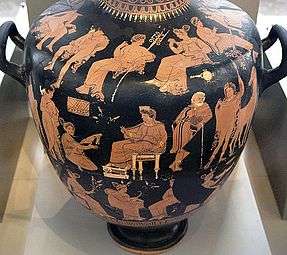

Mystery religions, sacred mysteries or simply mysteries, were religious schools of the Greco-Roman world for which participation was reserved to initiates (mystai).[1] The main characterization of this religion is the secrecy associated with the particulars of the initiation and the ritual practice, which may not be revealed to outsiders. The most famous mysteries of Greco-Roman antiquity were the Eleusinian Mysteries, which were of considerable antiquity and predated the Greek Dark Ages. The mystery schools flourished in Late Antiquity; Julian the Apostate in the mid 4th century is known to have been initiated into three distinct mystery schools — most notably the Mithraic Mysteries. Due to the secret nature of the school, and because the mystery religions of Late Antiquity were persecuted by the Christian Roman Empire from the 4th century, the details of these religious practices are derived from descriptions, imagery and cross-cultural studies. "Because of this element of secrecy, we are ill-informed as to the beliefs and practices of the various mystery faiths. We know that they had a general likeness to one another".[2]:50f

Justin Martyr in the 2nd century explicitly noted and identified them as "demonic imitations" of the true faith, and that "the devils, in imitation of what was said by Moses, asserted that Proserpine was the daughter of Jupiter, and instigated the people to set up an image of her under the name of Kore" (First Apology). Through the 1st to 4th century, Christianity stood in direct competition for adherents with the mystery schools, insofar as the "mystery schools too were an intrinsic element of the non-Jewish horizon of the reception of the Christian message". They too were "embraced by the process of the inculturation of Christianity in its initial phase", and they made "their own contribution to this process".[3]:152 In Klauck and McNeil's opinion, "the Christian doctrine of the sacraments, in the form in which we know it, would not have arisen without this interaction; and Christology too understood how to 'take up' the mythical inheritance, purifying it and elevating it".[3]:152

Definition

The term "Mystery" derives from Latin mysterium, from Greek mysterion (usually as the plural mysteria μυστήρια), in this context meaning "secret rite or doctrine". An individual who followed such a "Mystery" was a mystes, "one who has been initiated", from myein "to close, shut", a reference to secrecy (closure of "the eyes and mouth")[4]:56 or that only initiates were allowed to observe and participate in rituals. The Mysteries were thus schools in which all religious functions were closed to the uninitiated and for which the inner workings of the school were kept secret from the general public.

Characteristics

Mystery religions form one of three types of Hellenistic religion, the others being the imperial cult or ethnic religion particular to a nation or state, and the philosophic religions such as Neoplatonism. This is also reflected in the tripartite division of "theology" by Varro, in civil theology (concerning the state religion and its stabilizing effect on society), natural theology (philosophical speculation about the nature of the divine) and mythical theology (concerning myth and ritual).

Mysteries thus supplement rather than compete with civil religion. An individual could easily observe the rites of the state religion, be an initiate in one or several mysteries, and at the same time adhere to a certain philosophical school.[5]:99 In contrast to the public rituals of civil religion, participation in which was expected of every member of society, initiation to a mystery was optional within Graeco-Roman polytheism. Many of the aspects of public religion are repeated within the mystery, sacrifices, ritual meals, ritual purifications, etc., just with the additional aspect that they take place in secrecy, confined to a closed set of initiates.[3]:86 This is important in the context of the early persecution of Christians. Christianity was seen as objectionable by the Roman establishment not on grounds of its tenets or practices, but because early Christians chose to consider their faith as precluding the participation in the imperial cult, which was seen as subversive by the Roman establishment.

The mystery schools offered a niche for the preservation of ancient religious ritual, and there is reason to assume that they were very conservative. The Eleusian Mysteries persisted for more than a millennium, more likely close to two millennia, during which period the ritual of public religion changed significantly, from the religions of the Bronze to Early Iron Age to the Hero cult of Hellenistic civilization and again to the imperial cult of the Roman era, while the ritual performances of the mysteries for all we know remained unchanged. "They had, more often than not, come up from a barbarous underworld. They were singularly persistent. The mysteries at Eleusis near Athens lasted for a thousand years; and there is reason to believe that they changed little during that long period".[2]:51

For this reason, what glimpses we do have of the older Greek mysteries have been taken as reflecting certain archaic aspects of common Indo-European religion, with parallels in Indo-Iranian religion.[6] The mystery schools of Greco-Roman antiquity include the Eleusinian Mysteries, the Dionysian Mysteries, and the Orphic Mysteries. Some of the many divinities that the Romans nominally adopted from other cultures also came to be worshipped in Mysteries, for instance, Egyptian Isis, Persian Mithraic Mysteries, Thracian/Phrygian Sabazius, and Phrygian Cybele.[7]:21

Later influence

The ancient mystery schools were a subject of fascination for 19th and early-20th century German and French classical scholars. This literature had an enormous influence on European culture in the late 19th century. Psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung borrowed metaphors from this literature to reframe his theories and the charismatic movement based on them.[8][9]

List of mystery schools

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Crystal, David, ed. (1995), "Mystery Religions", Cambridge Encyclopedia of The English Language, Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

- 1 2 Barnes, Ernest William (1947), The Rise of Christianity, p. 50f.

- 1 2 3 Klauck, Hans-Josef; McNeil, Brian (2003), The Religious Context of Early Christianity, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-567-08943-4. 81-152?

- ↑ Newberg, Andrew (2001), Why God Won't Go Away, New York: Ballantine

- ↑ Iles Johnson, Sarah (2007), "Mysteries", in Iles Johnson, Sarah, Ancient Religions, Cambridge: Belknap Press/Harvard UP, ISBN 978-0-674-02548-6

- ↑ Janda, Michael (2000), Eleusis: das indogermanische Erbe der Mysterien, (Habil. Thesis), Innsbruck.

- ↑ Hall, Manly P. (1928), The Secret Teachings of all ages, San Francisco: s.p.

- ↑ Noll, Richard.Mysteria: Jung and the Ancient Mysteries (unpublished page proofs, 1994)

- ↑ Noll, Richard. "Jung the Leontocephalus" (1999)

</references>

Further reading

- Alvar, Jaime. Romanising Oriental Gods: Myth, Salvation, and Ethics in the Cults of Cybele, Isis, and Mithras (Leiden, 2008).

- Aneziri, Sophia. Die Vereine der Dionysischen Techniten im Kontext der hellenistischen Gesellschaft (Stuttgart, 2003).

- Bowden, Hugh. Mystery Cults of the Ancient World (Princeton, Princeton UP, 2010).

- Bremmer, Jan N. Initiation into the Mysteries of the Ancient World (Berlin, 2014).

- Burkert, Walter (1987), Ancient Mystery Cults, Cambridge, Mass.

- Casadio, Giovanni Casadio and Johnston, Patricia A. (eds), Mystic Cults in Magna Graecia (Austin, TX, University of Texas Press, 2009).

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), "Mystery", Encyclopædia Britannica, Cambridge: Cambridge UP

- Cosmopoulos, Michael B. (ed), Greek Mysteries: the archaeology and ritual of ancient Greek secret cults (London, Routledge, 2003).

- Delneri, Francesca, I culti misterici stranieri nei frammenti della commedia attica antica (Bologna, Patron Editore, 2006) (Eikasmos, Studi, 13).

- Dodds, Eric R. (1968), The Greeks and the Irrational, Berkeley: UC Press

- Frazer, James G. (1957), The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion, London: Macmillan

- Kirk, Geoffrey S. (1970), Myth: Its Meaning and Function in Ancient and Other Cultures, Cambridge: Cambridge UP

- Le Guen, Brigitte. Les Associations de Technites dionysiaques à l'époque hellénistique, 2 vol. (Nancy, 2001).

- Meyer, W. M. (1987), The Ancient Mysteries: A Sourcebook. Sacred Texts of the Mystery Religions of the Ancient Mediterranean World, San Francisco

- Virgili, Antonio, Culti misterici ed orientali a Pompei (Roma, Gangemi, 2008).

- Willoughby, H. R. (1929), Pagan Regeneration: Study of Mystery Initiations in the Graeco-Roman World, Chicago

External links

Media related to Mysteric religions in ancient world at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mysteric religions in ancient world at Wikimedia Commons