Musical notation

Music notation or musical notation is any system used to visually represent aurally perceived music through the use of written symbols, including ancient or modern musical symbols. Types and methods of notation have varied between cultures and throughout history, and much information about ancient music notation is fragmentary.

Although many ancient cultures used symbols to represent melodies, none of them is nearly as comprehensive as written language, limiting our modern understanding. Comprehensive music notation began to be developed in Europe in the Middle Ages, and has been adapted to many kinds of music worldwide.

History

Ancient Near East

The earliest form of musical notation can be found in a cuneiform tablet that was created at Nippur, in Sumer (today's Iraq), in about 2000 BC. The tablet represents fragmentary instructions for performing music, that the music was composed in harmonies of thirds, and that it was written using a diatonic scale.[1] A tablet from about 1250 BC shows a more developed form of notation.[2] Although the interpretation of the notation system is still controversial, it is clear that the notation indicates the names of strings on a lyre, the tuning of which is described in other tablets.[3] Although they are fragmentary, these tablets represent the earliest notated melodies found anywhere in the world.[4]

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greek musical notation was in use from at least the 6th century BC until approximately the 4th century AD; several complete compositions and fragments of compositions using this notation survive. The notation consists of symbols placed above text syllables. An example of a complete composition is the Seikilos epitaph, which has been variously dated between the 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD.

Three hymns by Mesomedes of Crete exist in manuscript. The Delphic Hymns, dated to the 2nd century BC, also use this notation, but they are not completely preserved. Ancient Greek notation appears to have fallen out of use around the time of the Decline of the Roman Empire.

Byzantine Empire

Byzantine music has mainly survived as music for court ceremonies, including vocal religious music. The question, whether it is based on the monodic modal singing and instrumental music of Ancient Greece, must remain open. Greek theoretical categories played a key role to understand and transmit Byzantine music, especially the tradition of Damascus had a strong impact on the pre-Islamic Near East comparable to Persian music and its music theoretical transfer in Sanskrit.

Unlike Western notation Byzantine neumes always indicate modal steps in relation to a clef or modal key (modal signatures which had been in use since papyrus fragments dating back to the 6th century). Originally this key or the incipit of a common melody was enough to indicate a certain melodic model given within the echos, despite ekphonetic notation further early melodic notation developed not earlier than between the 9th and the 10th century.[5] Like the Greek alphabet notational signs are ordered left to right (though the direction could be adapted like in certain Syriac manuscripts), the question of rhythm was entirely based on cheironomia, well-known melodical phrases given by gestures of the choirleaders which existed once as part of an oral tradition.

Today the main difference between Western and Eastern neumes is that Eastern notation symbols are differential rather than absolute, i.e. they indicate pitch steps (rising, falling or at the same step), and the musicians know to deduce correctly, from the score and the note they are singing presently, which correct interval is meant. These step symbols themselves, or better "phonic neumes", resemble brush strokes and are colloquially called gántzoi ("hooks") in Modern Greek.

Notes as pitch classes or modal keys (usually memorised by modal signatures) are represented in written form only between these neumes (in manuscripts usually written in red ink). In modern notation they simply serve as an optional reminder and modal and tempo directions have been added, if necessary. In Papadic notation medial signatures usually meant a temporary change into another echos.

The so-called "great signs" were once related to cheironomic signs, according to modern interpretations they are understood as embellishments and microtonal attractions (pitch changes smaller than a semitone), both essential in Byzantine chant.[6]

Since Chrysanthos of Madytos there are seven standard note names used for "solfège" (parallagē) pá, vú, ghá, dhē, ké, zō, nē, while the older practice still used the four enechemata or intonation formulas of the four echoi given by the modal signatures, the authentic or "kyrioi" in ascending direction, and the plagal or "plagioi" in descending direction (Papadic Octoechos).[7] With exception of vú and zō they do roughly correspond to Western solmization syllables as re, mi, fa, sol, la, si, do. Byzantine music uses the eight natural, non-tempered scales whose elements were identified by Ēkhoi, "sounds", exclusively, and therefore the absolute pitch of each note may slightly vary each time, depending on the particular Ēkhos used. Byzantine notation is still used in many Orthodox Churches. Sometimes cantors also use transcriptions into Western or Kievan staff notation while adding non-notatable embellishment material from memory and "sliding" into the natural scales from experience, but even concerning modern neume editions since the reform of Chrysanthos a lot of details are only known from an oral tradition related to traditional masters and their experience.

13th-century Near East

In 1252, Safi al-Din al-Urmawi developed a form of musical notation, where rhythms were represented by geometric representation. Many subsequent scholars of rhythm have sought to develop graphical geometrical notations. For example, a similar geometric system was published in 1987 by Kjell Gustafson, whose method represents a rhythm as a two-dimensional graph.[8]

Early Europe

Scholar and music theorist Isidore of Seville, writing in the early 7th century, considered that "unless sounds are held by the memory of man, they perish, because they cannot be written down."[9] By the middle of the 9th century, however, a form of neumatic notation began to develop in monasteries in Europe as a mnemonic device for Gregorian chant, using symbols known as neumes; the earliest surviving musical notation of this type is in the Musica disciplina of Aurelian of Réôme, from about 850. There are scattered survivals from the Iberian Peninsula before this time, of a type of notation known as Visigothic neumes, but its few surviving fragments have not yet been deciphered.[10] The problem with this notation was that it only showed melodic contours and consequently the music could not be read by someone who did not know the music already.

Notation had developed far enough to notate melody, but there was still no system for notating rhythm. A mid-13th-century treatise, De Mensurabili Musica, explains a set of six rhythmic modes that were in use at the time,[11] although it is not clear how they were formed. These rhythmic modes were all in triple time and rather limited rhythm in chant to six different repeating patterns. This was a flaw seen by German music theorist Franco of Cologne and summarised as part of his treatise Ars cantus mensurabilis (the art of measured chant, or mensural notation). He suggested that individual notes could have their own rhythms represented by the shape of the note. Not until the 14th century did something like the present system of fixed note lengths arise. The use of regular measures (bars) became commonplace by the end of the 17th century.

The founder of what is now considered the standard music stave was Guido d'Arezzo,[12] an Italian Benedictine monk who lived from about 991 until after 1033. He taught the use of solmization syllables based on a hymn to Saint John the Baptist, which begins Ut Queant Laxis and was written by the Lombard historian Paul the Deacon. The first stanza is:

- Ut queant laxis

- resonare fibris,

- Mira gestorum

- famuli tuorum,

- Solve polluti

- labii reatum,

- Sancte Iohannes.

Guido used the first syllable of each line, Ut, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, and La, to read notated music in terms of hexachords; they were not note names, and each could, depending on context, be applied to any note. In the 17th century, Ut was changed in most countries except France to the easily singable, "open" syllable Do, said to have been taken from the name of the Italian theorist Giovanni Battista Doni.[13]

Modern staff notation

Modern music notation originated in European classical music and is now used by musicians of many different genres throughout the world.

The system uses a five-line staff. Pitch is shown by placement of notes on the staff (sometimes modified by accidentals), and duration is shown with different note values and additional symbols such as dots and ties. Notation is read from left to right, which makes setting music for right-to-left scripts difficult.

A staff (or stave, in British English) of written music generally begins with a clef, which indicates the position of one particular note on the staff. The treble or G clef was originally a letter G and it identifies the second line up on the five line staff as the note G above middle C. The bass or F clef shows the position of the note F below middle C. Notes representing a pitch outside of the scope of the five line staff can be represented using ledger lines, which provide a single note with additional lines and spaces.

Following the clef, the key signature on a staff indicates the key of the piece by specifying that certain notes are flat or sharp throughout the piece, unless otherwise indicated.

Following the key signature is the time signature. Measures (bars) divide the piece into groups of beats, and the time signatures specify those groupings.

Directions to the player regarding matters such as tempo, dynamics and expression appear above or below the staff. For vocal music, lyrics are written. For short pauses (breaths), retakes (looks like ') are added.

In music for ensembles, a "score" shows music for all players together, while "parts" contain only the music played by an individual musician. A score can be constructed from a complete set of parts and vice versa. The process can be laborious but computer software offers a more convenient and flexible method.

Specialized notation conventions

- Percussion notation conventions are varied because of the wide range of percussion instruments. Percussion instruments are generally grouped into two categories: pitched and non-pitched. The notation of non-pitched percussion instruments is the more problematic and less standardized.

- Figured bass notation originated in Baroque basso continuo parts. It is also used extensively in accordion notation. The bass notes of the music are conventionally notated, along with numbers and other signs that determine the chords to play. It does not, however, specify the exact pitches of the harmony, leaving that for the performer to improvise.

- A lead sheet specifies only the melody, lyrics and harmony, using one staff with chord symbols placed above and lyrics below. It is used to capture the essential elements of a popular song without specifying how the song should be arranged or performed.

- A chord chart or "chart" contains little or no melodic information at all but provides detailed harmonic and rhythmic information, using slash notation and rhythmic notation. This is the most common kind of written music used by professional session musicians playing jazz or other forms of popular music and is intended primarily for the rhythm section (usually containing piano, guitar, bass and drums).

- Simpler chord charts for songs may contain only the chord changes, placed above the lyrics where they occur. Such charts depend on prior knowledge of the melody, and are used as reminders in performance or informal group singing.

- The shape note system is found in some church hymnals, sheet music, and song books, especially in the Southern United States. Instead of the customary elliptical note head, note heads of various shapes are used to show the position of the note on the major scale. Sacred Harp is one of the most popular tune books using shape notes.

Notation in various countries

India

The Indian scholar and musical theorist Pingala (c. 200 BC), in his Chanda Sutra, used marks indicating long and short syllables to indicate meters in Sanskrit poetry.

In the notation of Indian rāga, a solfege-like system called sargam is used. As in Western solfege, there are names for the seven basic pitches of a major scale (Shadja, Rishabh, Gandhar, Madhyam, Pancham, Dhaivat and Nishad, usually shortened Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Dha Ni). The tonic of any scale is named Sa, and the dominant Pa. Sa is fixed in any scale, and Pa is fixed at a fifth above it (a Pythagorean fifth rather than an equal-tempered fifth). These two notes are known as achala swar ('fixed notes').

Each of the other five notes, Re, Ga, Ma, Dha and Ni, can take a 'regular' (shuddha) pitch, which is equivalent to its pitch in a standard major scale (thus, shuddha Re, the second degree of the scale, is a whole-step higher than Sa), or an altered pitch, either a half-step above or half-step below the shuddha pitch. Re, Ga, Dha and Ni all have altered partners that are a half-step lower (Komal-"flat") (thus, komal Re is a half-step higher than Sa).

Ma has an altered partner that is a half-step higher (teevra-"sharp") (thus, tivra Ma is an augmented fourth above Sa). Re, Ga, Ma, Dha and Ni are called vikrut swar ('movable notes'). In the written system of Indian notation devised by Ravi Shankar, the pitches are represented by Western letters. Capital letters are used for the achala swar, and for the higher variety of all the vikrut swar. Lowercase letters are used for the lower variety of the vikrut swar.

Other systems exist for non-twelve-tone equal temperament and non-Western music, such as the Indian Swaralipi.

Russia

In Byzantium and Russia, sacred music was notated with special 'hooks and banners'. (See Byzantine Empire)

China

The earliest known examples of text referring to music in China are inscriptions on musical instruments found in the Tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng (d. 433 B.C.). Sets of 41 chimestones and 65 bells bore lengthy inscriptions concerning pitches, scales, and transposition. The bells still sound the pitches that their inscriptions refer to. Although no notated musical compositions were found, the inscriptions indicate that the system was sufficiently advanced to allow for musical notation. Two systems of pitch nomenclature existed, one for relative pitch and one for absolute pitch. For relative pitch, a solmization system was used.[14]

Gongche notation used Chinese characters for the names of the scale.

Korea

Jeong-gan-bo (or Chong Gan Bo, 정간보, 井間譜) is traditional Korean musical notation system introduced by Sejong the Great and known as the first musical notation system that is able to represent durations of notes in the Eastern. Among various kinds of Korean traditional music, Jeong-gan-bo targets a particular genre, Jeong-ak (정악, 正樂).

Japan

Japanese music is highly diversified, and therefore requires various systems of notation. In Japanese shakuhachi music, for example, glissandos and timbres are often more significant than distinct pitches, whereas taiko notation focuses on discrete strokes.

Indonesia

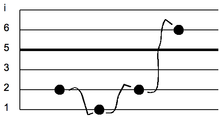

Notation plays a relatively minor role in the oral traditions of Indonesia. However, in Java and Bali, several systems were devised beginning at the end of the 19th century, initially for archival purposes. Today the most widespread are cipher notations ("not angka" in the broadest sense) in which the pitches are represented with some subset of the numbers 1 to 7, with 1 corresponding to either highest note of a particular octave, as in Sundanese gamelan, or lowest, as in the kepatihan notation of Javanese gamelan.

Notes in the ranges outside the central octave are represented with one or more dots above or below the each number. For the most part, these cipher notations are mainly used to notate the skeletal melody (the balungan) and vocal parts (gerongan), although transcriptions of the elaborating instrument variations are sometimes used for analysis and teaching. Drum parts are notated with a system of symbols largely based on letters representing the vocables used to learn and remember drumming patterns; these symbols are typically laid out in a grid underneath the skeletal melody for a specific or generic piece.

The symbols used for drum notation (as well as the vocables represented) are highly variable from place to place and performer to performer. In addition to these current systems, two older notations used a kind of staff: the Solonese script could capture the flexible rhythms of the pesinden with a squiggle on a horizontal staff, while in Yogyakarta a ladder-like vertical staff allowed notation of the balungan by dots and also included important drum strokes. In Bali, there are a few books published of Gamelan gender wayang pieces, employing alphabetical notation in the old Balinese script.

Composers and scholars both Indonesian and foreign have also mapped the slendro and pelog tuning systems of gamelan onto the western staff, with and without various symbols for microtones. The Dutch composer Ton de Leeuw also invented a three line staff for his composition Gending. However, these systems do not enjoy widespread use.

In the second half of the twentieth century, Indonesian musicians and scholars extended cipher notation to other oral traditions, and a diatonic scale cipher notation has become common for notating western-related genres (church hymns, popular songs, and so forth). Unlike the cipher notation for gamelan music, which uses a "fixed Do" (that is, 1 always corresponds to the same pitch, within the natural variability of gamelan tuning), Indonesian diatonic cipher notation is "moveable-Do" notation, so scores must indicate which pitch corresponds to the number 1 (for example, "1=C").

-

A short melody in slendro notated using the Surakarta method.[1]

-

The same notated using the Yogyakarta method or 'chequered notation'.[1]

-

The same notated using Kepatihan notation.[1]

Other systems and practices

Cipher notation

Cipher notation systems assigning Arabic numerals to the major scale degrees have been used at least since the Iberian organ tablatures of the 16th-century and include such exotic adaptations as Siffernotskrift. The one most widely in use today is the Chinese Jianpu, discussed in the main article. Numerals can of course also be assigned to different scale systems, as in the Javanese kepatihan notation described above.

Solfège

Solfège is a way of assigning syllables to names of the musical scale. In order, they are today: Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Ti Do' (for the octave). The classic variation is: Do Re Mi Fa Sol La Si Do'. The first Western system of functional names for the musical notes was introduced by Guido of Arezzo (c. 991 – after 1033), using the beginning syllables of the first six musical lines of the Latin hymn Ut queant laxis. The original sequence was Ut Re Mi Fa Sol La, where each verse started a scale note higher. "Ut" later became "Do". The equivalent syllables used in Indian music are: Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Dha Ni. See also: solfège, sargam, Kodály hand signs.

Tonic sol-fa is a type of notation using the initial letters of solfège.

Letter notation

The notes of the 12-tone scale can be written by their letter names A–G, possibly with a trailing sharp or flat symbol, such as A♯ or B♭.

Tablature

Tablature was first used in the Middle Ages for organ music and later in the Renaissance for lute music.[15] In most lute tablatures, a staff is used, but instead of pitch values, the lines of the staff represent the strings of the instrument. The frets to finger are written on each line, indicated by letters or numbers. Rhythm is written separately with one or another variation of standard note values indicating the duration of the slowest moving part. Few seem to have remarked on the fact that tablature combines in one notation system both the physical and technical requirements of play (the lines and symbols on them and in relation to each other representing the actual performance actions) with the unfolding of the music itself (the lines of tablature taken horizontally represent the actual temporal unfolding of the music). In later periods, lute and guitar music was written with standard notation. Tablature caught interest again in the late 20th century for popular guitar music and other fretted instruments, being easy to transcribe and share over the internet in ASCII format. Websites like Tablature#OLGA.net[16] (currently off-line pending legal disputes) have archives of text-based popular music tablature.

Klavar notation

Piano roll based notations

Some chromatic systems have been created taking advantage of the layout of black and white keys of the standard piano keyboard. The "staff" is most widely referred to as "piano roll", created by extending the black and white piano keys.

Chromatic staff notations

Over the past three centuries, hundreds of music notation systems have been proposed as alternatives to traditional western music notation. Many of these systems seek to improve upon traditional notation by using a "chromatic staff" in which each of the 12 pitch classes has its own unique place on the staff. Examples are the Ailler-Brennink notation, Jacques-Daniel Rochat's Dodeka[17] system, Tom Reed's Twinline notation, Russell Ambrose's Ambrose Piano Tabs,[18] Paul Morris' TwinNote,[19] John Keller's Express Stave, and José A. Sotorrio's Bilinear Music Notation. These notation systems do not require the use of standard key signatures, accidentals, or clef signs. They also represent interval relationships more consistently and accurately than traditional notation. The Music Notation Project (formerly known as the Music Notation Modernization Association) has a website with information on many of these notation systems.[20]

Graphic notation

The term 'graphic notation' refers to the contemporary use of non-traditional symbols and text to convey information about the performance of a piece of music. Practitioners include Christian Wolff, Earle Brown, Anthony Braxton, John Cage, Morton Feldman, Krzysztof Penderecki, Cornelius Cardew, and Roger Reynolds. See Notations, edited by John Cage and Alison Knowles, ISBN 0-685-14864-5.

Simplified Music Notation

Simplified Music Notation is an alternative form of musical notation designed to make sight-reading easier. It is based on classical staff notation, but incorporates sharps and flats into the shape of the note heads. Notes such as double sharps and double flats are written at the pitch they are actually played at, but preceded by symbols called history signs that show they have been transposed.

Modified Stave Notation

Modified Stave Notation (MSN) is an alternative way of notating music for people who cannot easily read ordinary musical notation even if it is enlarged.

Parsons code

Parsons code is used to encode music so that it can be easily searched.

Braille music

Braille music is a complete, well developed, and internationally accepted musical notation system that has symbols and notational conventions quite independent of print music notation. It is linear in nature, similar to a printed language and different from the two-dimensional nature of standard printed music notation. To a degree Braille music resembles musical markup languages[21] such as MusicXML[22] or NIFF.

Integer notation

In integer notation, or the integer model of pitch, all pitch classes and intervals between pitch classes are designated using the numbers 0 through 11.

Rap notation

The standard form of rap notation is the "flow diagram", where rappers line up their lyrics underneath "beat numbers".[23] Hip-hop scholars also make use of the same flow diagrams that rappers use: the books How to Rap and How to Rap 2 extensively use the diagrams to explain rap's triplets, flams, rests, rhyme schemes, runs of rhyme, and breaking rhyme patterns, among other techniques.[24] Similar systems are used by musicologists Adam Krims in his book Rap Music and the Poetics of Identity[25] and Kyle Adams in his work on rap's flow.[26] As rap revolves around a strong 4/4 beat,[27] with certain syllables aligned to the beat, all the notational systems have a similar structure: they all have four beat numbers at the top of the diagram, so that syllables can be written in-line with the beat.[27]

Music notation on computer

Many computer programs have been developed for creating music notation (called scorewriters or music notation software). Music may also be stored in various digital file formats for purposes other than graphic notation output.

Perspectives of musical notation in composition and musical performance

According to Philip Tagg and Richard Middleton, musicology and to a degree European-influenced musical practice suffer from a 'notational centricity', a methodology slanted by the characteristics of notation.[28]

Patents

In some countries, new musical notations can be patented. In the United States, for example, about 90 patents have been issued for new notation systems. The earliest patent, U.S. Patent 1,383 was published in 1839.

See also

- List of musical symbols of modern notation.

- Jewish Torah Trope Cantillation

- Colored music notation

- Eye movement in music reading

- Guido of Arezzo, inventor of modern musical notation

- History of music publishing

- List of scorewriters

- Mensural notation

- Modal notation

- Music engraving

- Music OCR

- Neume (plainchant notation)

- Pitch class

- Rastrum

- Scorewriter

- Sheet music

- Time unit box system, a notation system useful for polyrhythms

- Tongan music notation, a subset of standard music notation

- Tonnetz

- Znamenny chant

Notes

- ↑ Kilmer & Civil 1986,.

- ↑ Kilmer 1965,.

- ↑ West 1994, 161–63.

- ↑ West 1994, 161.

- ↑ Today we can only the study the evolution of notation within Greek monastic chant books like those of the sticherarion and the heirmologion, while there is no authentic asmatikon and kontakarion of the Constantinopolitan cathedral rite. The earliest books which have survived, are in Slavonic translation which already show an own notation system (see Russia) used in Novgorod and Macedonia during the 12th century.

- ↑ See Maria Alexandru (2000) for a historical discussion of the great signs and their modern interpretations.

- ↑ Chrysanthos (1832) made a difference between his monosyllabic and the traditional polysyllabic parallage.

- ↑ Toussaint 2004, 3.

- ↑ Isidore of Seville 2006, 95.

- ↑ Zapke 2007,

- ↑ Christensen 2002, 628.

- ↑ Otten 1910.

- ↑ McNaught 1893, 43.

- ↑ Bagley 2004.

- ↑ Apel 1961, xxiii and 22.

- ↑ olga.net Archived 24 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ dodeka.info

- ↑ ambrosepianotabs.com

- ↑ twinnote.org

- ↑ musicnotation.org

- ↑ musicmarkup.info

- ↑ emusician.com Archived 1 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Edwards 2009, 67.

- ↑ Edwards 2013, 53.

- ↑ Krims 2001, 59–60.

- ↑ Adams 2009.

- 1 2 Edwards 2009, 69.

- ↑ Tagg 1979, 28–32; Middleton 1990, 104–6.

References

- Adams, Kyle (2009). "On the Metrical Techniques of Flow in Rap Music". Music Theory Online 5, no. 9 (October) (accessed 4 April 2014).

- Alexandru, Maria (2000). Studie über die 'großen Zeichen' der byzantinischen musikalischen Notation unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Periode vom Ende des 12. bis Anfang des 19. Jahrhunderts. Universität Kopenhagen.

- Apel, Willi (1961). The Notation of Polyphonic Music, 900–1600, 5th edition, revised and with commentary. Publications of the Mediaeval Academy of America, no. 38. Cambridge, Mass.: Mediaeval Academy of America.

- Bagley, Robert (2004). "The Prehistory of Chinese Music Theory". Elsley Zeitlyn Lecture on Chinese Archaeology and Culture. (Tuesday 26 October) British Academy's Autumn 2004 Lecture Programme. London: British Academy. Abstract. Accessed 30 May 2010.

- Christensen, Thomas (2002). The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Chrysanthos of Madytos (1832). Θεωρητικὸν μέγα τῆς Μουσικῆς. Triest: Michele Weis. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- Edwards, Paul (2009). How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC, with a foreword by Kool G. Rap. Chicago: Chicago Review Press.

- Edwards, Paul (2013). How to Rap 2: Advanced Flow and Delivery Techniques, foreword by Gift of Gab. Chicago: Chicago Review Press.

- Isidore of Seville (2006). The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, translated with introduction and notes by Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach, and Oliver Berghof, with the collaboration of Muriel Hall. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83749-1 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-511-21969-6 (ebook) (accessed 8 September 2012).

- Kilmer, Anne Draffkorn (1965). "The Strings of Musical Instruments: Their Names, Numbers, and Significance", in Studies in Honor of Benno Landsberger on His Seventy-fifth Birthday, April 21, 1965, Assyriological Studies 16, edited by Hans G. Güterbock and Thorkild Jacobsen, 261–68. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

- Kilmer, Anne Draffkorn, and Miguel Civil (1986). "Old Babylonian Musical Instructions Relating to Hymnody". Journal of Cuneiform Studies 38, no. 1:94–98.

- Krims, Adam (2001). Rap Music And The Poetics Of Identity. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Lindsay, Jennifer (1992). Javanese Gamelan. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-588582-1.

- McNaught, W. G. (1893). "The History and Uses of the Sol-fa Syllables". Proceedings of the Musical Association 19 (January): 35–51. ISSN 0958-8442 (accessed 23 April 2010).

- Otten, J. (1910). "Guido of Arezzo". The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved May 30, 2010 from New Advent.

- Paolo, Tortiglione (2012). Semiography and Semiology of Contemporary Music. Milan: Rugginenti. ISBN 978-88-7665-616-3

- Schneider, Albrecht (1987). "Musik, Sound, Sprache, Schrift: Transkription und Notation in der Vergleichenden Musikwissenschaft und Musikethnologie". Zeitschrift für Semiotik 9, nos. 3–4:317–43.

- Sotorrio, José A. (1997). Bilinear Music Notation: A New Notation System for the Modern Musician. Spectral Music. ISBN 978-0-9548498-2-5.

- Tagg, Philip (1979). Kojak—50 Seconds of Television Music: Toward the Analysis of Affect in Popular Music. Skrifter från Musikvetenskapliga Institutionen, Göteborg 2. Göteborg: Musikvetenskapliga Institutionen, Göteborgs Universitet. ISBN 91-7222-235-2 (Rev. translation of "Kojak—50 sekunders tv-musik")

- Touma, Habib Hassan (1996). The Music of the Arabs, new expanded edition, translated by Laurie Schwartz. With accompanying CD recording. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-88-8

- Toussaint, Godfried (2004). "A Comparison of Rhythmic Similarity Measures". Technical Report SOCS-TR-2004.6. Montréal: School of Computer Science, McGill University.

- West, M[artin]. L[itchfield]. (1994). "The Babylonian Musical Notation and the Hurrian Melodic Texts". Music & Letters 75, no. 2. (May): 161–179

- Williams, Charles Francis Abdy (1903). "The Story of Notation." New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Zapke, Susana (ed.) (2007). Hispania Vetus: Musical-Liturgical Manuscripts from Visigothic Origins to the Franco-Roman Transition (9th–12th Centuries), with a foreword by Anscario M Mundó. Bilbao: Fundación BBVA. ISBN 978-84-96515-50-5

Further reading

- Hall, Rachael (2005). Math for Poets and Drummers. Saint Joseph's University.

- Gayou, Évelyne. "Transcrire les musiques électroacoustiques." eContact! 12.4—Perspectives on the Electroacoustic Work / Perspectives sur l'œuvre électroacoustique (August 2010). Montréal: CEC. (French)

- Gould, Elaine (2011). "Behind Bars - The Definitive Guide to Music Notation". London: Faber Music.

- Karakayali, Nedim (2010). "Two Assemblages of Cultural Transmission: Musicians, Political Actors and Educational Techniques in the Ottoman Empire and Western Europe". Journal of Historical Sociology 23, no. 3:343–71.

- Lieberman, David (2006). Game Enhanced Music Manuscript. In GRAPHITE '06: Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques in Australasia and South East Asia, Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia), 29 November–2 December 2006, edited by Y Tina Lee, Siti Mariyam Shamsuddin, Diego Gutierrez, and Norhaida Mohd Suaib, 245–50. New York: ACM Press. ISBN 1-59593-564-9

- Middleton, Richard (1990/2002). Studying Popular Music. Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 0-335-15275-9.

- Read, Gardner (1978). Modern Rhythmic Notation. Victor Gollance Ltd.

- Read, Gardner (1987). Source Book of Proposed Music Notation Reforms. Greenwood Press.

- Reisenweaver, Anna (2012). "Guido of Arezzo and His Influence on Music Learning", Musical Offerings: Vol. 3: No. 1, Article 4. Available at http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol3/iss1/4.

- Savas, Savas I. (1965). Byzantine Music in Theory and Practice (PDF). Boston: Hercules. ISBN 0-916586-24-3. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- Stone, Kurt (1980). Music Notation in the Twentieth Century: A Practical Guidebook. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Strayer, Hope R. (2013) "From Neumes to Notes: The Evolution of Music Notation," Musical Offerings: Vol. 4: No. 1, Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol4/iss1/1

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Music:Music Notation Systems |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Musical notation. |

- Byzantine Music Notation. Contains a Guide to Byzantine Music Notation (neumes).

- CCARH—Center for Computer Assisted Research in the Humanities Information on Stanford University Course on music representation. Links page shows examples of different notations.

- Music Markup Language. XML-based language for music notation.

- Synopsis of Musical Notation Encyclopedias (An index from topics of CWN into the books of Gould, Vinci, Wanske, Stone and Read.)

- Byrd, Don. "Extremes of Conventional Musical Notation."

- Gehrkens, Karl Wilson Music Notation and Terminology. Project Gutenberg.

- Gilbert, Nina. "Glossary of U.S. and British English musical terms." Posted 17 June 1998; updated 7 September 2000.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|