World egg

The world egg, cosmic egg or mundane egg is a mythological motif found in the creation myths of many cultures and civilizations. Typically, the world egg is a beginning of some sort, and the universe or some primordial being comes into existence by "hatching" from the egg, sometimes lain on the primordial waters of the Earth.[1][2]

Vedic mythology

One of the earliest ideas of "egg-shaped cosmos" comes from some of the Sanskrit scriptures. The Sanskrit term for it is Brahmanda (ब्रह्माण्ड) which is derived from two words- 'Brahm' (ब्रह्म) means 'cosmos' or 'expanding' and 'anda' (अण्ड) means 'egg'. Certain Puranas such as the Brahmanda Purana speak of this in detail.

The Rig Veda (RV 10.121) uses a similar name for the source of the universe: Hiranyagarbha (हिरण्यगर्भ) which literally means "golden fetus" or "golden womb". The Upanishads elaborate that the Hiranyagarbha floated around in emptiness for a while, and then broke into two halves which formed Dyaus (Heaven) and Prithvi (Earth). The Rig Veda has a similar coded description of the division of the universe in its early stages.

Greek mythology

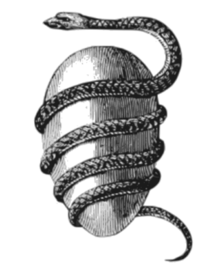

The Orphic Egg in the Ancient Greek Orphic tradition is the cosmic egg from which hatched the primordial hermaphroditic deity Phanes/Protogonus (variously equated also with Zeus, Pan, Metis, Eros, Erikepaios and Bromius) who in turn created the other gods.[3] The egg is often depicted with a serpent wound around it.

Many threads of earlier myths are apparent in the new tradition. Phanes was believed to have been hatched from the World-Egg of Chronos (Time) and Ananke (Necessity). His older wife Nyx (Night) called him Protogenus. As she created nighttime, he created daytime. He also created the method of creation by mingling. He was made the ruler of the deities and passed the sceptre to Nyx. This new Orphic tradition states that Nyx later gave the sceptre to her son Uranos before it passed to Cronus and then to Zeus, who retained it.

Egyptian mythology

In the original myth concerning the Ogdoad, the world arose from the waters as a mound of dirt, which was deified as Hathor. Ra was contained within an egg laid upon this mound by a celestial bird. In the earliest version of this myth, the bird is a goose (it is not explained where the goose originates). However, after the rise of the cult of Thoth, the egg was said to have been a gift from Thoth and laid by an ibis, the bird with which he was associated.

Phoenician mythology

A philosophical creation story traced to "the cosmogony of Taautus, whom Philo of Byblos explicitly identified with the Egyptian Thoth—"the first who thought of the invention of letters, and began the writing of records"— which begins with Erebus and Wind, between which Eros 'Desire' came to be. From this was produced Môt which seems to be the Phoenician/Ge'ez/Hebrew/Arabic/Ancient Egyptian word for 'Death' but which the account says may mean 'mud'. In a mixed confusion, the germs of life appear, and intelligent animals called Zophasemin (explained probably correctly as 'observers of heaven') formed together as an egg, perhaps. The account is not clear. Then Môt burst forth into light and the heavens were created and the various elements found their stations.

Following the etymological line of Jacob Bryant one might also consider with regard to the meaning of Môt, that according to the Ancient Egyptians Ma'at was the personification of the fundamental order of the universe, without which all of creation would perish. She was also considered the wife of Thoth.

Chinese mythology

In the myth of Pangu, developed by Taoist monks hundreds of years after Lao Zi, the universe began as an egg. A god named Pangu, born inside the egg, broke it into two halves: the upper half became the sky, while the lower half became the earth. As the god grew taller, the sky and the earth grew thicker and were separated further. Finally Pangu died and his body parts became different parts of the earth.

Finnish mythology

In the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic, there is a myth of the world being created from the fragments of an egg laid by a diving duck on the knee of Ilmatar, goddess of the air:

- One egg's lower half transformed

- And became the earth below,

- And its upper half transmuted

- And became the sky above;

- From the yolk the sun was made,

- Light of day to shine upon us;

- From the white the moon was formed,

- Light of night to gleam above us;

- All the colored brighter bits

- Rose to be the stars of heaven

- And the darker crumbs changed into

- Clouds and cloudlets in the sky.

In many original folk poems, the duck - or sometimes an eagle - laids its eggs on the knee of Väinämöinen. [4]

Polynesian mythology

In Cook Islands mythology, deep within Avaiki (the Underworld), a place described as resembling a vast hollow coconut shell, there dwelt in the deepest depths, the primordial mother goddess, Varima-te-takere. Her domain was described as being so narrow, that her knees touched her chin. It was from this place that she created the first man, Avatea, a god of light, a hybrid being half man and half fish. He was sent to the Upperworld to shine light in the land of men, and his eyes were believed to be the sun and the moon.[5]

Representations

- In the temple of Daibod, Japan, it is represented as a nest egg floating in an expanse of water.

- On the island of Cyprus, the egg is represented as a gigantic egg-shaped vase.[6]

Modern mythology

In 1955 poet and writer Robert Graves published the mythography The Greek Myths, a compendium of Greek mythology normally published in two volumes. Within this work Graves' imaginatively reconstructed "Pelasgian creation myth" features a supreme creatrix, Eurynome, "The Goddess of All Things",[7] who arose naked from Chaos to part sea from sky so that she could dance upon the waves. Catching the north wind at her back and, rubbing it between her hands, she warms the pneuma and spontaneously generates the serpent Ophion, who mates with her. In the form of a dove upon the waves, she lays the Cosmic Egg and bids Ophion to incubate it by coiling seven times around until it splits in two and hatches "all things that exist... sun, moon, planets, stars, the earth with its mountains and rivers, its trees, herbs, and living creatures".[7] [8]

In modern cosmology

The concept was resurrected by modern science in the 1930s and explored by theoreticians during the following two decades. The idea comes from a perceived need to reconcile Edwin Hubble's observation of an expanding universe (which was also predicted from Einstein's equations of general relativity by Alexander Friedmann) with the notion that the universe must be eternally old. Current cosmological models maintain that 13.8 billion years ago, the entire mass of the universe was compressed into a gravitational singularity, the so-called cosmic egg, from which it expanded to its current state (following the Big Bang).

Georges Lemaitre proposed in 1927 that the cosmos originated from what he called the primeval atom.

In the late 1940s, George Gamow's assistant cosmological researcher Ralph Alpher, proposed the name ylem for the primordial substance that existed between the big crunch of the previous universe and the big bang of our own universe.[9]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Mundane Egg —". Infoplease.com. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ "Brewer, E. Cobham. Dictionary of Phrase & Fable. Mundane Egg (The)". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- ↑ West, M. L. (1983) The Orphic Poems. Oxford:Oxford University Press. p. 205

- ↑ Martti Haavio: Väinämöinen: Suomalaisten runojen keskushahmo. Porvoo: WSOY, 1950

- ↑ William Wyatt Gill (1876). Myths and Songs from the South Pacific. London: Henry S. King & Co.

- ↑ Northvegr: The Northern Way

- 1 2 Graves, Robert (1990) [1955]. The Greek Myths 1. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-001026-8.

- ↑ "Books: The Goddess & the Poet". TIME. July 18, 1955. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

- ↑ The Cosmos--Voyage Through the Universe series, New York:1988 Time-Life Books Page 75

References

- Eino Friberg, trans., The Kalevala: Epic of the Finnish People. Otava Publishing Company, Ltd., 4th ed., p. 44. (1998) ISBN 951-1-10137-4

- Elias Lönnrot, Kalevala. (1849)