Multiple zeta function

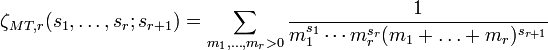

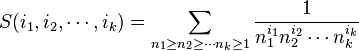

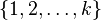

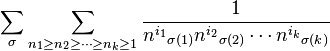

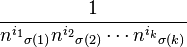

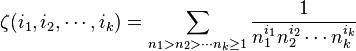

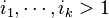

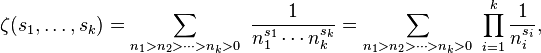

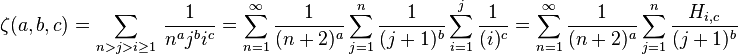

In mathematics, the multiple zeta functions are generalisations of the Riemann zeta function, defined by

and converge when Re(s1) + ... + Re(si) > i for all i. Like the Riemann zeta function, the multiple zeta functions can be analytically continued to be meromorphic functions (see, for example, Zhao (1999)). When s1, ..., sk are all positive integers (with s1 > 1) these sums are often called multiple zeta values (MZVs) or Euler sums.

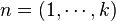

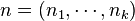

The k in the above definition is named the "length" of a MZV, and the n = s1 + ... + sk is known as the "weight".[1]

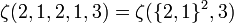

The standard shorthand for writing multiple zeta functions is to place repeating strings of the argument within braces and use a superscript to indicate the number of repetitions. For example,

Two parameters case

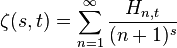

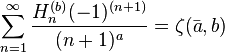

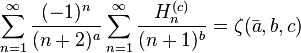

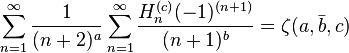

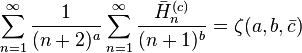

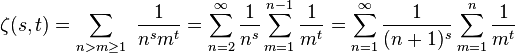

In the particular case of only two parameters we have (with s>1 and n,m integer):[2]

where

where  are the generalized harmonic numbers.

are the generalized harmonic numbers.

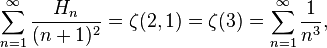

Multiple zeta functions are known to satisfy what is known as MZV duality, the simplest case of which is the famous identity of Euler:

where Hn are the harmonic numbers.

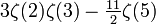

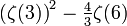

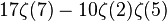

Special values of double zeta functions, with s > 0 and even, t > 1 and odd, but s+t=2N+1 (taking if necessary ζ(0) = 0):[2]

| s | t | approximate value | explicit formulae | OEIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

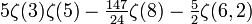

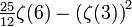

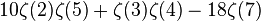

| 2 | 2 | 0.811742425283353643637002772406 |  | |

| 3 | 2 | 0.228810397603353759768746148942 |  | |

| 4 | 2 | 0.088483382454368714294327839086 |  | |

| 5 | 2 | 0.038575124342753255505925464373 |  | |

| 6 | 2 | 0.017819740416835988 | ||

| 2 | 3 | 0.711566197550572432096973806086 |  | |

| 3 | 3 | 0.213798868224592547099583574508 |  | |

| 4 | 3 | 0.085159822534833651406806018872 |  | |

| 5 | 3 | 0.037707672984847544011304782294 |  | |

| 2 | 4 | 0.674523914033968140491560608257 |  | |

| 3 | 4 | 0.207505014615732095907807605495 |  | |

| 4 | 4 | 0.083673113016495361614890436542 |  |

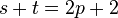

Note that if  we have

we have  irreducibles, i.e. these MZVs cannot be written as function of

irreducibles, i.e. these MZVs cannot be written as function of  only.[3]

only.[3]

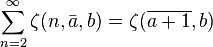

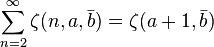

Three parameters case

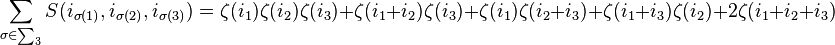

In the particular case of only three parameters we have (with a>1 and n,j,i integer):

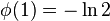

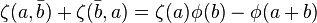

Euler reflection formula

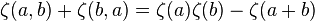

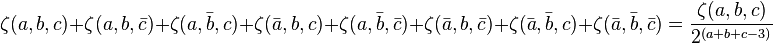

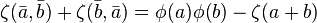

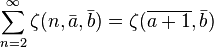

The above MZVs satisfy the Euler reflection formula:

for

for

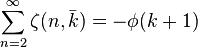

Using the shuffle relations, it is easy to prove that:[3]

for

for

This function can be seen as a generalization of the reflection formulas.

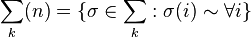

Symmetric sums in terms of the zeta function

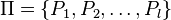

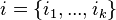

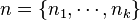

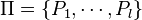

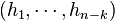

Let  , and for a partition

, and for a partition  of the set

of the set  , let

, let  . Also, given such a

. Also, given such a  and a k-tuple

and a k-tuple  of exponents, define

of exponents, define  .

.

The relations between the  and

and  are:

are:

and

and

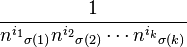

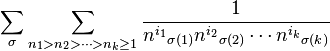

Theorem 1(Hoffman)

For any real  ,

,  .

.

Proof. Assume the  are all distinct. (There is not loss of generality, since we can take limits.) The left-hand side can be written as

are all distinct. (There is not loss of generality, since we can take limits.) The left-hand side can be written as

. Now thinking on the symmetric

. Now thinking on the symmetric

group  as acting on k-tuple

as acting on k-tuple  of positive integers. A given k-tuple

of positive integers. A given k-tuple  has an isotropy group

has an isotropy group

and an associated partition

and an associated partition  of

of  :

:  is the set of equivalence classes of the relation

given by

is the set of equivalence classes of the relation

given by  iff

iff  , and

, and  . Now the term

. Now the term  occurs on the left-hand side of

occurs on the left-hand side of  exactly

exactly  times. It occurs on the right-hand side in those terms corresponding to partitions

times. It occurs on the right-hand side in those terms corresponding to partitions  that are refinements of

that are refinements of  : letting

: letting  denote refinement,

denote refinement,  occurs

occurs  times. Thus, the conclusion will follow if

times. Thus, the conclusion will follow if

for any k-tuple

for any k-tuple  and associated partition

and associated partition  .

To see this, note that

.

To see this, note that  counts the permutations having cycle-type specified by

counts the permutations having cycle-type specified by  : since any elements of

: since any elements of  has a unique cycle-type specified by a partition that refines

has a unique cycle-type specified by a partition that refines  , the result follows.[4]

, the result follows.[4]

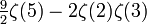

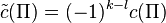

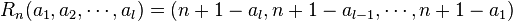

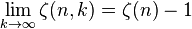

For  , the theorem says

, the theorem says  for

for  . This is the main result of.[5]

. This is the main result of.[5]

Having  . To state the analog of Theorem 1 for the

. To state the analog of Theorem 1 for the  , we require one bit of notation. For a partition

, we require one bit of notation. For a partition

or

or  , let

, let  .

.

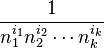

Theorem 2(Hoffman)

For any real  ,

,  .

.

Proof. We follow the same line of argument as in the preceding proof. The left-hand side is now

, and a term

, and a term  occurs on the left-hand since once if all the

occurs on the left-hand since once if all the  are distinct, and not at all otherwise. Thus, it suffices to show

are distinct, and not at all otherwise. Thus, it suffices to show

(1)

(1)

To prove this, note first that the sign of  is positive if the permutations of cycle-type

is positive if the permutations of cycle-type  are even, and negative if they are odd: thus, the left-hand side of (1) is the signed sum of the number of even and odd permutations in the isotropy group

are even, and negative if they are odd: thus, the left-hand side of (1) is the signed sum of the number of even and odd permutations in the isotropy group  . But such an isotropy group has equal numbers of even and odd permutations unless it is trivial, i.e. unless the associated partition

. But such an isotropy group has equal numbers of even and odd permutations unless it is trivial, i.e. unless the associated partition  is

is

.[4]

.[4]

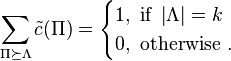

The sum and duality conjectures[4]

We first state the sum conjecture, which is due to C. Moen.[6]

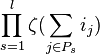

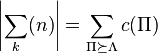

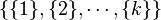

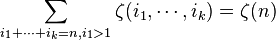

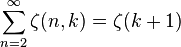

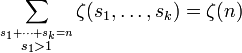

Sum conjecture(Hoffman). For positive integers k and n,

, where the sum is extended over k-tuples

, where the sum is extended over k-tuples  of positive integers with

of positive integers with  .

.

Three remarks concerning this conjecture are in order. First, it implies

. Second, in the case

. Second, in the case  it says that

it says that  , or using the relation between the

, or using the relation between the  and

and  and Theorem 1,

and Theorem 1,

This was proved by Euler's paper[7] and has been rediscovered several times, in particular by Williams.[8] Finally, C. Moen[6] has proved the same conjecture for k=3 by lengthy but elementary arguments.

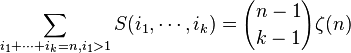

For the duality conjecture, we first define an involution  on the set

on the set  of finite sequences of positive integers whose first element is greater than 1. Let

of finite sequences of positive integers whose first element is greater than 1. Let  be the set of strictly increasing finite sequences of positive integers, and let

be the set of strictly increasing finite sequences of positive integers, and let  be the function that sends a sequence in

be the function that sends a sequence in  to its sequence of partial sums. If

to its sequence of partial sums. If  is the set of sequences in

is the set of sequences in  whose last element is at most

whose last element is at most  , we have two commuting involutions

, we have two commuting involutions  and

and  on

on  defined by

defined by

and

and

= complement of

= complement of  in

in  arranged in increasing order. The our definition of

arranged in increasing order. The our definition of  is

is  for

for  with

with  .

.

For example,

We shall say the sequences

We shall say the sequences  and

and  are dual to each other, and refer to a sequence fixed by

are dual to each other, and refer to a sequence fixed by  as self-dual.[4]

as self-dual.[4]

Duality conjecture (Hoffman). If  is dual to

is dual to  , then

, then  .

.

This sum conjecture is also known as Sum Theorem, and it may be expressed as follows: the Riemann zeta value of an integer n ≥ 2 is equal to the sum of all the valid (i.e. with s1 > 1) MZVs of the partitions of length k and weight n, with 1 ≤ k ≤n − 1. In formula:[1]

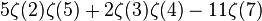

For example with length k = 2 and weight n = 7:

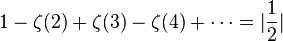

Euler sum with all possible alternations of sign

The Euler sum with alternations of sign appears in studies of the non-alternating Euler sum.[3]

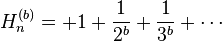

Notation

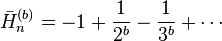

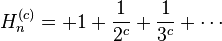

with

with  are the generalized harmonic numbers.

are the generalized harmonic numbers. with

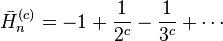

with

with

with

with

with

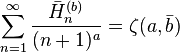

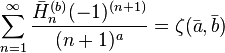

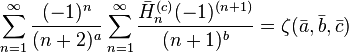

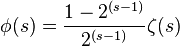

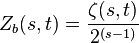

As a variant of the Dirichlet eta function we define

with

with

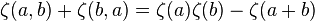

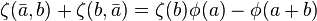

Reflection formula

The reflection formula  can be generalized as follows:

can be generalized as follows:

if  we have

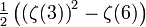

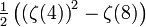

we have ![\zeta(\bar{a},\bar{a})=\tfrac{1}{2}\Big[\phi^2(a)-\zeta(2a)\Big]](../I/m/5296a48391cb350b9c2732713c3a9b1f.png)

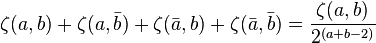

Other relations

Using the series definition it is easy to prove:

with

with

with

with

A further useful relation is:[3]

where ![Z_a(s,t)=\zeta(s,t)+\zeta(\bar{s},t)-\frac{\Big[\zeta(s,t)+\zeta(s+t)\Big]}{2^{(s-1)}}](../I/m/18ba0ab236ef1b9b72bd130494f3ba74.png) and

and

Note that  must be used for all value

must be used for all value  for whom the argument of the factorials is

for whom the argument of the factorials is

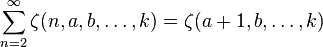

Other results

For any integer positive : :

:

or more generally:

or more generally:

Mordell–Tornheim zeta values

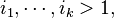

The Mordell–Tornheim zeta function, introduced by Matsumoto (2003) who was motivated by the papers Mordell (1958) and Tornheim (1950), is defined by

It is a special case of the Shintani zeta function.

References

- Tornheim, Leonard (1950). "Harmonic double series". American Journal of Mathematics 72: 303–314. doi:10.2307/2372034. ISSN 0002-9327. MR 0034860.

- Mordell, Louis J. (1958). "On the evaluation of some multiple series". Journal of the London Mathematical Society. Second Series 33: 368–371. doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-33.3.368. ISSN 0024-6107. MR 0100181.

- Apostol, Tom M.; Vu, Thiennu H. (1984), "Dirichlet series related to the Riemann zeta function", Journal of Number Theory 19 (1): 85–102, doi:10.1016/0022-314X(84)90094-5, ISSN 0022-314X, MR 0751166

- Crandall, Richard E.; Buhler, Joe P. (1994). "On the evaluation of Euler Sums". Experimental Mathematics 3 (4): 275. doi:10.1080/10586458.1994.10504297. MR 1341720.

- Borwein, Jonathan M.; Girgensohn, Roland (1996). "Evaluation of Triple Euler Sums". El. J. Combinat. 3 (1): #R23. MR 1401442.

- Flajolet, Philippe; Salvy, Bruno (1998). "Euler Sums and contour integral representations". Exp. Math. 7.

- Zhao, Jianqiang (1999). "Analytic continuation of multiple zeta functions". Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 128 (5): 1275–1283. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-99-05398-8. MR 1670846.

- Matsumoto, Kohji (2003), "On Mordell–Tornheim and other multiple zeta-functions", Proceedings of the Session in Analytic Number Theory and Diophantine Equations, Bonner Math. Schriften 360, Bonn: Univ. Bonn, MR 2075634

- Espinosa, Olivier; Moll, Victor H. (2008). "The evaluation of Tornheim double sums". arXiv:0811.0557.

- Espinosa, Olivier; Moll, Victor H. (2010). "The evaluation of Tornheim double sums II". Ramanujan J. 22: 55–99. doi:10.1007/s11139-009-9181-1. MR 2610609.

- Borwein, J.M.; Chan, O-Y. (2010). "Duality in tails of multiple zeta values". Int. J. Number Theory 6 (3): 501–514. doi:10.1142/S1793042110003058. MR 2652893.

- Basu, Ankur (2011). "On the evaluation of Tornheim sums and allied double sums". Ramanujan J. 26 (2): 193–207. doi:10.1007/s11139-011-9302-5. MR 2853480.

Notes

- 1 2 Hoffman, Mike. "Multiple Zeta Values". Mike Hoffman's Home Page. U.S. Naval Academy. Retrieved June 8, 2012.

- 1 2 Borwein, David; Borwein, Jonathan; Bradley, David (September 23, 2004). "Parametric Euler Sum Identities" (PDF). CARMA, AMSI Honours Course. The University of Newcastle. Retrieved June 3, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Broadhurst, D. J. (1996). "On the enumeration of irreducible k-fold Euler sums and their roles in knot theory and field theory.". arXiv:hep-th/9604128.

- 1 2 3 4 Hoffman, Michael (1992). "Multiple Harmonic Series". Pacific Journal of Mathematics 152: 276–278. doi:10.2140/pjm.1992.152.275. MR 1141796. Zbl 0763.11037.

- ↑ Ramachandra Rao, R. Sita; M. V. Subbarao (1984). "Transformation formulae for multiple series". Pacific Journal of Mathematics 113: 417–479. doi:10.2140/pjm.1984.113.471.

- 1 2 Moen, C. "Sums of Simple Series". Preprint.

- ↑ Euler, L. (1775). "Meditationes circa singulare serierum genus". Novi Comm. Acad. Sci. Petropol 15 (20): 140–186.

- ↑ Williams, G. T. (1958). "On the evaluation of some multiple series". Journal of the London Mathematical Society 33: 368–371. doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-33.3.368.

External links

- Borwein, Jonathan; Zudilin, Wadim. "Lecture notes on the Multiple Zeta Function".

- Hoffman, Michael (2012). "Multiple zeta values".

![\zeta(s,t)=\zeta(s)\zeta(t)+\tfrac{1}{2}\Big[\tbinom{s+t}{s}-1\Big]\zeta(s+t)-\sum_{r=1}^{N-1}\Big[\tbinom{2r}{s-1}+\tbinom{2r}{t-1}\Big]\zeta(2r+1)\zeta(s+t-1-2r)](../I/m/2a377306860dd65a4877db1c7abbee69.png)

![\zeta(a,b)+\zeta(\bar{a},\bar{b})=\sum_{s>0} (a+b-s-1)!\Big[\frac{Z_a(a+b-s,s)}{(a-s)!(b-1)!}+\frac{Z_b(a+b-s,s)}{(b-s)!(a-1)!}\Big]](../I/m/c540846e453618a86ad7e307aa86571d.png)

![\zeta(a,a)=\tfrac{1}{2}\Big[(\zeta(a))^{2}-\zeta(2a)\Big]](../I/m/684027e0d244679d0f236687e08217b5.png)