Quadratic sieve

The quadratic sieve algorithm (QS) is an integer factorization algorithm and, in practice, the second fastest method known (after the general number field sieve). It is still the fastest for integers under 100 decimal digits or so, and is considerably simpler than the number field sieve. It is a general-purpose factorization algorithm, meaning that its running time depends solely on the size of the integer to be factored, and not on special structure or properties. It was invented by Carl Pomerance in 1981 as an improvement to Schroeppel's linear sieve.[1]

Basic aim

The algorithm attempts to set up a congruence of squares modulo n (the integer to be factorized), which often leads to a factorization of n. The algorithm works in two phases: the data collection phase, where it collects information that may lead to a congruence of squares; and the data processing phase, where it puts all the data it has collected into a matrix and solves it to obtain a congruence of squares. The data collection phase can be easily parallelized to many processors, but the data processing phase requires large amounts of memory, and is difficult to parallelize efficiently over many nodes or if the processing nodes do not each have enough memory to store the whole matrix. The block Wiedemann algorithm can be used in the case of a few systems each capable of holding the matrix.

The naive approach to finding a congruence of squares is to pick a random number, square it, and hope the least non-negative remainder modulo n is a perfect square (in the integers). For example, 802 mod 5959 is 441, which is 212. This approach finds a congruence of squares only rarely for large n, but when it does find one, more often than not, the congruence is nontrivial and the factorization is complete. This is roughly the basis of Fermat's factorization method.

The quadratic sieve is a modification of Dixon's factorization method.

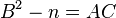

The general running time required for the quadratic sieve (to factor an integer n) is

in the L-notation.[2]

The constant e is the base of the natural logarithm.

The approach

Let x mod y denote the remainder after dividing x by y. To factorize the integer n, Fermat's method entails a search for a single number a, n1/2<a<n-1, such that a2 mod n is a square. But these a are hard to find. The quadratic sieve consists of computing a2 mod n for several a, then finding a subset of these whose product is a square. This will yield a congruence of squares.

For example, 412 mod 1649 = 32, 422 mod 1649 = 115, and 432 mod 1649 is 200. None of these are squares, but the product (32)(200) = 6400 = 802, and mod 1649, (32)(200) = (412)(432) = ((41)(43))2 The preceding sentence is unclear.. Since (41)(43) mod 1649 = 114, this gives a congruence of squares: 1142 ≡ 802 (mod 1649). To finish this factorization example, continue reading Congruence of squares.

But how will this solve the problem of, given a set of numbers, finding a subset whose product is a square? The solution uses the concept of an exponent vector. For example, the prime-power factorization of 504 is 23325071. It can be represented by the exponent vector (3,2,0,1), which gives the exponents of 2, 3, 5, and 7 in the prime factorization. The number 490 would similarly have the vector (1,0,1,2). Multiplying the numbers is the same as componentwise adding their exponent vectors: (504)(490) has the vector (4,2,1,3).

A number is a square if every number in its exponent vector is even. For example, the vectors (3,0,0,1) and (1,2,0,1) add to (4,2,0,2), so (56)(126) is a square. Searching for a square requires knowledge only of the parity of the numbers in the vectors, so it is possible to reduce the entire vector mod 2 and perform addition of elements mod 2: (1,0,0,1) + (1,0,0,1) = (0,0,0,0). This is particularly efficient in practical implementations, as the vectors can be represented as bitsets and addition mod 2 reduces to bitwise XOR.

The problem is reduced to: given a set of (0,1)-vectors, find a subset which adds to the zero vector mod 2. This is a linear algebra problem; the solution is a linear dependency. It is a theorem of linear algebra that with more vectors than each vector has elements, such a dependency must exist. It can be found efficiently, for example by placing the vectors as rows in a matrix and then using Gaussian elimination, which is easily adapted to work for integers mod 2 instead of real numbers. The desired square is then the product of the numbers corresponding to those vectors.

However, simply squaring many random numbers mod n produces a very large number of different prime factors, and so very long vectors and a very large matrix. The answer is to look specifically for numbers a such that a2 mod n has only small prime factors (they are smooth numbers). They are harder to find, but using only smooth numbers keeps the vectors and matrices smaller and more tractable. The quadratic sieve searches for smooth numbers using a technique called sieving, discussed later, from which the algorithm takes its name.

The algorithm

To summarize, the basic quadratic sieve algorithm has these main steps:

- Choose a smoothness bound B. The number π(B), denoting the number of prime numbers less than B, will control both the length of the vectors and the number of vectors needed.

- Use sieving to locate π(B) + 1 numbers ai such that bi=(ai2 mod n) is B-smooth.

- Factor the bi and generate exponent vectors mod 2 for each one.

- Use linear algebra to find a subset of these vectors which add to the zero vector. Multiply the corresponding ai together naming the result mod n: a and the bi together which yields a B-smooth square b2.

- We are now left with the equality a2=b2 mod n from which we get two square roots of (a2 mod n), one by taking the square root in the integers of b2 namely b, and the other the a computed in step 4.

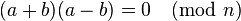

- We now have the desired identity:

. Compute the GCD of n with the difference (or sum) of a and b. This produces a factor, although it may be a trivial factor (n or 1). If the factor is trivial, try again with a different linear dependency or different a.

. Compute the GCD of n with the difference (or sum) of a and b. This produces a factor, although it may be a trivial factor (n or 1). If the factor is trivial, try again with a different linear dependency or different a.

The remainder of this article explains details and extensions of this basic algorithm.

How QS optimizes finding congruences

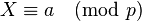

The quadratic sieve attempts to find pairs of integers x and y(x) (where y(x) is a function of x) satisfying a much weaker condition than x2 ≡ y2 (mod n). It selects a set of primes called the factor base, and attempts to find x such that the least absolute remainder of y(x) = x2 mod n factorizes completely over the factor base. Such x values are said to be smooth with respect to the factor base.

The factorization of a value of y(x) that splits over the factor base, together with the value of x, is known as a relation. The quadratic sieve speeds up the process of finding relations by taking x close to the square root of n. This ensures that y(x) will be smaller, and thus have a greater chance of being smooth.

This implies that y is on the order of 2x[√n]. However, it also implies that y grows linearly with x times the square root of n.

Another way to increase the chance of smoothness is by simply increasing the size of the factor base. However, it is necessary to find at least one smooth relation more than the number of primes in the factor base, to ensure the existence of a linear dependency.

Partial relations and cycles

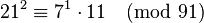

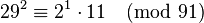

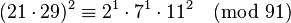

Even if for some relation y(x) is not smooth, it may be possible to merge two of these partial relations to form a full one, if the two y 's are products of the same prime(s) outside the factor base. [Note that this is equivalent to extending the factor base.] For example, if the factor base is {2, 3, 5, 7} and n = 91, there are partial relations:

Multiply these together:

and multiply both sides by (11−1)2 modulo 91. 11−1 modulo 91 is 58, so:

producing a full relation. Such a full relation (obtained by combining partial relations) is called a cycle. Sometimes, forming a cycle from two partial relations leads directly to a congruence of squares, but rarely.

Checking smoothness by sieving

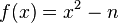

There are several ways to check for smoothness of the ys. The most obvious is by trial division, although this increases the running time for the data collection phase. Another method that has some acceptance is the elliptic curve method (ECM). In practice, a process called sieving is typically used. If f(x) is the polynomial f(x)=x^2-n we have

Thus solving f(x) ≡ 0 (mod p) for x generates a whole sequence of y=f(x)s which are divisible by p. This is finding a square root modulo a prime, for which there exist efficient algorithms, such as the Shanks–Tonelli algorithm. (This is where the quadratic sieve gets its name: y is a quadratic polynomial in x, and the sieving process works like the Sieve of Eratosthenes.)

The sieve starts by setting every entry in a large array A[] of bytes to zero. For each p, solve the quadratic equation mod p to get two roots α and β, and then add an approximation to log(p) to every entry for which y(x) = 0 mod p ... that is, A[kp + α] and A[kp + β]. It is also necessary to solve the quadratic equation modulo small powers of p in order to recognise numbers divisible by the square of a factor-base prime.

At the end of the factor base, any A[] containing a value above a threshold of roughly log(n) will correspond to a value of y(x) which splits over the factor base. The information about exactly which primes divide y(x) has been lost, but it has only small factors, and there are many good algorithms (trial division by small primes, SQUFOF, Pollard rho, and ECM are usually used in some combination) for factoring a number known to have only small factors.

There are many y(x) values that work, so the factorization process at the end doesn't have to be entirely reliable; often the processes misbehave on say 5% of inputs, requiring a small amount of extra sieving.

Example of basic sieve

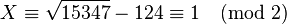

This example will demonstrate standard quadratic sieve without logarithm optimizations or prime powers. Let the number to be factored N = 15347, therefore the ceiling of the square root of N is 124. Since N is small, the basic polynomial is enough: y(x) = (x + 124)2 − 15347.

Data collection

Since N is small, only 4 primes are necessary. The first 4 primes p for which 15347 has a square root mod p are 2, 17, 23, and 29 (in other words, 15347 is a quadratic residue modulo each of these primes). These primes will be the basis for sieving.

Now we construct our sieve  of

of  and begin the sieving process for each prime in the basis, choosing to sieve the first 0 ≤ X < 100 of Y(X):

and begin the sieving process for each prime in the basis, choosing to sieve the first 0 ≤ X < 100 of Y(X):

The next step is to perform the sieve. For each p in our factor base  solve the equation

solve the equation

to find the entries in the array V which are divisible by p.

For  solve

solve  to get the solution

to get the solution  .

.

Thus, starting at X=1 and incrementing by 2, each entry will be divisible by 2. Dividing each of those entries by 2 yields

Similarly for the remaining primes p in  the equation

the equation is solved. Note that for every p > 2, there will be 2 resulting linear equations due to there being 2 modular square roots.

is solved. Note that for every p > 2, there will be 2 resulting linear equations due to there being 2 modular square roots.

Each equation  results in

results in  being divisible by p at x=a and each pth value beyond that. Dividing V by p at a, a+p, a+2p, a+3p, etc., for each prime in the basis finds the smooth numbers which are products of unique primes (first powers).

being divisible by p at x=a and each pth value beyond that. Dividing V by p at a, a+p, a+2p, a+3p, etc., for each prime in the basis finds the smooth numbers which are products of unique primes (first powers).

Any entry of V that equals 1 corresponds to a smooth number. Since  ,

,  , and

, and  equal one, this corresponds to:

equal one, this corresponds to:

| X + 124 | Y | factors |

|---|---|---|

| 124 | 29 | 20 • 170 • 230 • 291 |

| 127 | 782 | 21 • 171 • 231 • 290 |

| 195 | 22678 | 21 • 171 • 231 • 291 |

Matrix processing

Since smooth numbers Y have been found with the property  , the remainder of the algorithm follows equivalently to any other variation of Dixon's factorization method.

, the remainder of the algorithm follows equivalently to any other variation of Dixon's factorization method.

Writing the exponents of the product of a subset of the equations

as a matrix  yields:

yields:

A solution to the equation is given by the left null space, simply

Thus the product of all 3 equations yields a square (mod N).

and

So the algorithm found

Testing the result yields GCD(3070860 - 22678, 15347) = 103, a nontrivial factor of 15347, the other being 149.

This demonstration should also serve to show that the quadratic sieve is only appropriate when n is large. For a number as small as 15347, this algorithm is overkill. Trial division or Pollard rho could have found a factor with much less computation.

Multiple polynomials

In practice, many different polynomials are used for y, since only one polynomial will not typically provide enough (x, y) pairs that are smooth over the factor base. The polynomials used must have a special form, since they need to be squares modulo n. The polynomials must all have a similar form to the original y(x) = x2 − n:

Assuming  is a multiple of A, so that

is a multiple of A, so that  the polynomial y(x) can be written as

the polynomial y(x) can be written as  . If then A is a square, only the factor

. If then A is a square, only the factor  has to be considered.

has to be considered.

This approach (called MPQS, Multiple Polynomial Quadratic Sieve) is ideally suited for parallelization, since each processor involved in the factorization can be given n, the factor base and a collection of polynomials, and it will have no need to communicate with the central processor until it is finished with its polynomials.

Large primes

One large prime

If, after dividing by all the factors less than A, the remaining part of the number (the cofactor) is less than A2, then this cofactor must be prime. In effect, it can be added to the factor base, by sorting the list of relations into order by cofactor. If y(a) = 7*11*23*137 and y(b) = 3*5*7*137, then y(a)y(b) = 3*5*11*23 * 72 * 1372. This works by reducing the threshold of entries in the sieving array above which a full factorization is performed.

More large primes

Reducing the threshold even further, and using an effective process for factoring y(x) values into products of even relatively large primes - ECM is superb for this - can find relations with most of their factors in the factor base, but with two or even three larger primes. Cycle finding then allows combining a set of relations sharing several primes into a single relation.

Parameters from realistic example

To illustrate typical parameter choices for a realistic example on a real implementation including the multiple polynomial and large prime optimizations, the tool msieve was run on a 267-bit semiprime, producing the following parameters:

- Trial factoring cutoff: 27 bits

- Sieve interval (per polynomial): 393216 (12 blocks of size 32768)

- Smoothness bound: 1300967 (50294 primes)

- Number of factors for polynomial A coefficients: 10 (see Multiple polynomials above)

- Large prime bound: 128795733 (26 bits) (see Large primes above)

- Smooth values found: 25952 by sieving directly, 24462 by combining numbers with large primes

- Final matrix size: 50294 × 50414, reduced by filtering to 35750 × 35862

- Nontrivial dependencies found: 15

- Total time (on a 1.6 GHz UltraSparc III): 35 min 39 seconds

- Maximum memory used: 8 MB

Factoring records

Until the discovery of the number field sieve (NFS), QS was the asymptotically fastest known general-purpose factoring algorithm. Now, Lenstra elliptic curve factorization has the same asymptotic running time as QS (in the case where n has exactly two prime factors of equal size), but in practice, QS is faster since it uses single-precision operations instead of the multi-precision operations used by the elliptic curve method.

On April 2, 1994, the factorization of RSA-129 was completed using QS. It was a 129-digit number, the product of two large primes, one of 64 digits and the other of 65. The factor base for this factorization contained 524339 primes. The data collection phase took 5000 MIPS-years, done in distributed fashion over the Internet. The data collected totaled 2GB. The data processing phase took 45 hours on Bellcore's (now Telcordia Technologies) MasPar (massively parallel) supercomputer. This was the largest published factorization by a general-purpose algorithm, until NFS was used to factor RSA-130, completed April 10, 1996. All RSA numbers factored since then have been factored using NFS.

The current QS record is a 135-digit cofactor of  , itself an Aurifeuillian factor of

, itself an Aurifeuillian factor of  , which was split into 66-digit and 69-digit prime factors in 2001.

, which was split into 66-digit and 69-digit prime factors in 2001.

Implementations

- PPMPQS and PPSIQS

- mpqs

- SIMPQS is a fast implementation of the self-initialising multiple polynomial quadratic sieve written by William Hart. It provides support for the large prime variant and uses Jason Papadopoulos' block Lanczos code for the linear algebra stage. SIMPQS is accessible as the qsieve command in the SAGE computer algebra package or can be downloaded in source form. SIMPQS is optimized for use on Athlon and Opteron machines, but will operate on most common 32- and 64-bit architectures. It is written entirely in C.

- a factoring applet by Dario Alpern, that uses the quadratic sieve if certain conditions are met.

- The PARI/GP computer algebra package includes an implementation of the self-initialising multiple polynomial quadratic sieve implementing the large prime variant. It was adapted by Thomas Papanikolaou and Xavier Roblot from a sieve written for the LiDIA project. The self initialisation scheme is based on an idea from the thesis of Thomas Sosnowski.

- A variant of the quadratic sieve is available in the MAGMA computer algebra package. It is based on an implementation of Arjen Lenstra from 1995, used in his "factoring by email" program.

- msieve, an implementation of the multiple polynomial quadratic sieve with support for single and double large primes, written by Jason Papadopoulos. Source code and a Windows binary are available.

- YAFU, written by Ben Buhrow, is similar to msieve but is faster for most modern processors. It uses Jason Papadopoulos' block Lanczos code. Source code and binaries for Windows and Linux are available.

- Ariel, a simple Java implementation of the quadratic sieve for didactic purposes.

- PSIQS, an open source Java package containing basic QS, MPQS and SIQS; quite readable and halfway performant.

- Java QS, an open source Java project containing basic implementation of QS. Released at February 4, 2016 by Ilya Gazman

See also

References

- ↑ Carl Pomerance, Analysis and Comparison of Some Integer Factoring Algorithms, in Computational Methods in Number Theory, Part I, H.W. Lenstra, Jr. and R. Tijdeman, eds., Math. Centre Tract 154, Amsterdam, 1982, pp 89-139.

- ↑ Pomerance, Carl (December 1996). "A Tale of Two Sieves" (PDF). Notices of the AMS 43 (12). pp. 1473–1485.

- Richard Crandall and Carl Pomerance (2001). Prime Numbers: A Computational Perspective (1st ed.). Springer. ISBN 0-387-94777-9. Section 6.1: The quadratic sieve factorization method, pp. 227–244.

Other external links

- Reference paper "The Quadratic Sieve Factoring Algorithm" by Eric Landquist

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![e^{(1 + o(1))\sqrt{\ln n \ln\ln n}} =L_n\left[1/2,1\right]](../I/m/21d8e2eec9895a736637fa2fa0136859.png)