Multipath propagation

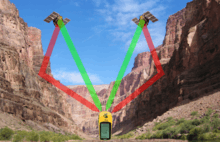

In wireless telecommunications, multipath is the propagation phenomenon that results in radio signals reaching the receiving antenna by two or more paths. Causes of multipath include atmospheric ducting, ionospheric reflection and refraction, and reflection from water bodies and terrestrial objects such as mountains and buildings.

Multipath causes multipath interference including constructive and destructive interference, and phase shifting of the signal. Destructive interference causes fading. Where the magnitudes of the signals arriving by the various paths have a distribution known as the Rayleigh distribution, this is known as Rayleigh fading. Where one component (often, but not necessarily, a line of sight component) dominates, a Rician distribution provides a more accurate model, and this is known as Rician fading.

Examples

In facsimile and (analog) television transmission, multipath causes jitter and ghosting, seen as a faded duplicate image to the right of the main image. Ghosts occur when transmissions bounce off a mountain or other large object, while also arriving at the antenna by a shorter, direct route, with the receiver picking up two signals separated by a delay.

In radar processing, multipath causes ghost targets to appear, deceiving the radar receiver. These ghosts are particularly bothersome since they move and behave like the normal targets (which they echo), and so the receiver has difficulty in isolating the correct target echo. These problems can be overcome by incorporating a ground map of the radar's surroundings and eliminating all echoes which appear to originate below ground or above a certain height.

In digital radio communications (such as GSM) multipath can cause errors and affect the quality of communications. The errors are due to intersymbol interference (ISI). Equalisers are often used to correct the ISI. Alternatively, techniques such as orthogonal frequency division modulation and rake receivers may be used.

In a Global Positioning System receiver, Multipath Effect can cause a stationary receiver's output to indicate as if it were randomly jumping about or creeping. When the unit is moving the jumping or creeping may be hidden, but it still degrades the displayed accuracy of location and speed.

In wired media

Multipath propagation may also happen in wired media, especially where impedance mismatch causes signal reflection. A well-known example is power line communication.

High-speed power line communication systems usually employ multi-carrier modulations (such as OFDM or Wavelet OFDM) to avoid the intersymbol interference that multipath propagation would cause.

The ITU-T G.hn standard provides a way to create a high-speed (up to 1 Gigabit/s) local area network using existing home wiring (power lines, phone lines and coaxial cables). G.hn uses OFDM with a cyclic prefix to avoid ISI. Because multipath propagation behaves differently in each kind of wire, G.hn uses different OFDM parameters (OFDM symbol duration, Guard Interval duration) for each media.

Mathematical modeling

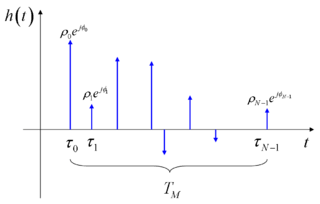

The mathematical model of the multipath can be presented using the method of the impulse response used for studying linear systems.

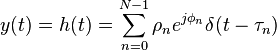

Suppose you want to transmit a single, ideal Dirac pulse of electromagnetic power at time 0, i.e.

At the receiver, due to the presence of the multiple electromagnetic paths, more than one pulse will be received (we suppose here that the channel has infinite bandwidth, thus the pulse shape is not modified at all), and each one of them will arrive at different times. In fact, since the electromagnetic signals travel at the speed of light, and since every path has a geometrical length possibly different from that of the other ones, there are different air travelling times (consider that, in free space, the light takes 3 μs to cross a 1 km span). Thus, the received signal will be expressed by

where  is the number of received impulses (equivalent to the number of electromagnetic paths, and possibly very large),

is the number of received impulses (equivalent to the number of electromagnetic paths, and possibly very large),  is the time delay of the generic

is the time delay of the generic  impulse, and

impulse, and  represent the complex amplitude (i.e., magnitude and phase) of the generic received pulse. As a consequence,

represent the complex amplitude (i.e., magnitude and phase) of the generic received pulse. As a consequence,  also represents the impulse response function

also represents the impulse response function  of the equivalent multipath model.

of the equivalent multipath model.

More in general, in presence of time variation of the geometrical reflection conditions, this impulse response is time varying, and as such we have

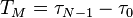

Very often, just one parameter is used to denote the severity of multipath conditions: it is called the multipath time,  , and it is defined as the time delay existing between the first and the last received impulses

, and it is defined as the time delay existing between the first and the last received impulses

In practical conditions and measurement, the multipath time is computed by considering as last impulse the first one which allows to receive a determined amount of the total transmitted power (scaled by the atmospheric and propagation losses), e.g. 99%.

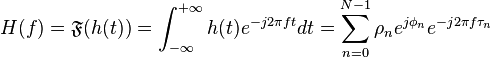

Keeping our aim at linear, time invariant systems, we can also characterize the multipath phenomenon by the channel transfer function  , which is defined as the continuous time Fourier transform of the impulse response

, which is defined as the continuous time Fourier transform of the impulse response

where the last right-hand term of the previous equation is easily obtained by remembering that the Fourier transform of a Dirac pulse is a complex exponential function, an eigenfunction of every linear system.

The obtained channel transfer characteristic has a typical appearance of a sequence of peaks and valleys (also called notches); it can be shown that, on average, the distance (in Hz) between two consecutive valleys (or two consecutive peaks), is roughly inversely proportional to the multipath time. The so-called coherence bandwidth is thus defined as

For example, with a multipath time of 3 μs (corresponding to a 1 km of added on-air travel for the last received impulse), there is a coherence bandwidth of about 330 kHz.

See also

- Choke ring antenna, a design that can reject extraneous multipath signals

- Diversity schemes

- Fading

- Multipath interference

- Olivia MFSK

- Orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing

- Signal flow

- Ultra wide-band

- Doppler spread

- Lloyd's mirror

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document "Federal Standard 1037C".

This article incorporates public domain material from the General Services Administration document "Federal Standard 1037C".

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||