Mountain yellow-legged frog

| Southern mountain yellow-legged frog | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Ranidae |

| Genus: | Rana |

| Species: | R. muscosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Rana muscosa Camp, 1917 | |

The mountain yellow-legged frog or southern mountain yellow-legged frog[1] (Rana muscosa) is a species of true frog endemic to California in the United States. It occurs in the San Jacinto Mountains, San Bernardino Mountains, and San Gabriel Mountains in Southern California and the Southern Sierra Nevada. It is a federally listed endangered species.[2]

Populations of Rana muscosa in the northern Sierra Nevada have been redescribed as a new species, Rana sierrae, the Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frog. This has been proposed as an endangered species as of 2013.[2] The mountains separating the headwaters of the South Fork and Middle Fork of the Kings River mark the boundary between the ranges of the two species.[1]

Description

Rana muscosa is 4 to 8.9 centimeters long. Its color and patterning are variable. It is yellowish, brownish, or olive with black and brown markings. Its species name muscosa is from the Latin meaning "mossy" or "full of moss", inspired by its coloration. It may have light orange or yellow thighs. When handled, the frog emits a defensive odor reminiscent of garlic.[3]

Habitat

The frog occurs in mountain creeks, lakes and lakeshores, streams, and pools, preferring sunny areas. It rarely strays far from water, and can remain underwater for a very long time, likely through cutaneous gas exchange. The tadpoles require a permanent water habitat for at least two years while they develop. The frog has been noted at elevations of between about 1,214 and 7,546 feet (370 and 2,300 meters) in Southern California.[1]

Biology

The frog emerges from its wintering site soon after snowmelt. Its breeding season begins once the highest meltwater flow is over, around March through May in the southern part of its range, and up to July in higher mountains to the north. Fertilization is external, and the egg cluster is secured to vegetation in a current, or in still waters sometimes left floating free. The juvenile may be a tadpole for 3 to 4 years before undergoing metamorphosis.[3]

The frog lacks a vocal sac. Its call is raspy, rising at the end. During the day, it calls underwater.[3]

This species feeds on insects such as beetles, ants, bees, wasps, flies, and dragonflies. It is also known to eat tadpoles.[3]

Conservation status

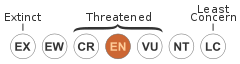

The frog is an endangered species under the US Endangered Species Act. The International Union for Conservation of Nature has also listed it as endangered.[1] Its NatureServe conservation status is Imperiled.[4]

Decline

Once a common species, Rana muscosa was absent from much of its native range by the 1970s. Over the course of the last hundred years, 90% of its populations have been eliminated.[5] The frog was known from 166 locations in the Southern California mountains, and as of 2007, only seven or eight remained.[1] The 2009 discovery of R. muscosa at two locations in the San Bernardino National Forest was newsworthy.[6] The frog is represented in the Sierra Nevada by three or four populations.[1] Its decline is attributed to many factors, including introduced species of fish such as trout, livestock grazing,[7] chytrid fungus,[8] and probably pesticides, drought, and ultraviolet radiation.[7]

Introduced fish species

Trout were introduced to lakes and streams throughout the Sierra Nevada in the late 1800s to increase recreational fishing in the area. The fish feed on tadpoles, a main prey item. The introduced trout have changed the distribution of several native species in the local ecosystems.[5] After the removal of fish from several lakes, the frog reappeared and its populations increased.[5] It then began to disperse to other suitable habitats nearby.[9]

Pesticides

The decline of the frog from its historic range has been associated with pesticide drift from agricultural areas.[10][11] Frogs that have been reintroduced to water bodies cleared of fish have failed to survive, and analysis has isolated pesticides in their tissues.[12] Pesticides are considered by some authorities to be a greater threat to the frog than the trout.[13] The relative roles that pesticides and introduced fish play in frog declines are still debated, and the loss of R. muscosa in its former range has probably been influenced by multiple factors.[12]

Chytridiomycosis

This species is one of many amphibians affected by the fungal disease chytridiomycosis. Ample research has explored the biology of the fungus and how to prevent related amphibian declines.[8] The fungus attacks keratinized areas of a frog's body. Tadpoles are not severely affected because only their jaw sheaths and tooth rows are heavily keratinized.[14] Infection in a tadpole can be identified by changes in the pigmentation of these parts.[15] Adults have keratin-rich skin and suffer worse infections.

In studies, well adult frogs exposed to infected frogs for at least two weeks developed the disease. Transmission takes longer in tadpoles, generally over seven weeks.[15] Frogs may be predisposed to infection if their immune systems are weakened by other factors, such as pesticide.[16] Studies indicate that R. muscosa is naturally more susceptible to the chytrid fungus than many other frogs to begin with.[17]

Conservation

The first successful captive breeding of the frog occurred in 2009 when three tadpoles were reared at the San Diego Zoo. Conservation workers at the zoo plan to release any more surviving captive-bred frogs in the San Jacinto Mountains, part of their native range.[18]

In 2015 frogs and tadpoles of the species were reintroduced to Fuller Mill Creek in the San Bernardino Mountains and San Bernardino National Forest. [19] They were bred and raised the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center for Conservation Research in Escondido, one of the organizations that have partnered with the San Diego Zoo Institute for Conservation Research (ICR) to save the species from extinction. [19] The Los Angeles Zoo is also a coalition partner and currently is holding two groups of wild collected tadpoles from two localities in the San Gabriel Mountains, to be they are old enough and conditions are supportive. [19]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hammerson, G. (2008). Rana muscosa. In: IUCN 2013. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.1. Downloaded on 05 August 2013.

- 1 2 Mountain yellow-legged frog (Rana muscosa), United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

- 1 2 3 4 Rana muscosa - Southern Mountain Yellow-legged Frog, California Herps: A Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. 2013.

- ↑ Rana muscosa, NatureServe. 2012.

- 1 2 3 Knapp, R. A., et al. (2007). "Removal of nonnative fish results in population expansion of a declining amphibian (mountain yellow-legged frog, Rana muscosa)' Biological Conservation 135(1):11-20.

- ↑ Nearly extinct California frog rediscovered. NBC News. July 24, 2009.

- 1 2 Vredenburg, V. The Mountain Yellow-legged Frog - Can They be Saved? Sierra Nature Notes Volume 1. January, 2001.

- 1 2 The Amphibian Chytrid Fungus and Chytridiomycosis. Amphibianark.org. Retrieved 04 August 2013.

- ↑ Vredenburg, V. T. (2004). Reversing introduced species effects: experimental removal of introduced fish leads to rapid recovery of a declining frog. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101(20):7646-50.

- ↑ Davidson, C., et al. (2002). Spatial tests of the pesticide drift, habitat destruction, UV-B, and climate-change hypotheses for California amphibian declines. Conservation Biology 16(6):1588-1601.

- ↑ Davidson, C. (2004). Declining downwind: amphibian population declines in California and historical pesticide use. Ecological Applications 14(6):1892-1902.

- 1 2 Davidson, C. and R. A. Knapp. (2007). Multiple stressors and amphibian declines: dual impacts of pesticides and fish on yellow-legged frogs. Ecological Applications 17(2):587-97.

- ↑ Taylor, S. K., et al. (1999). Effects of malathion on disease susceptibility in Woodhouse's toads. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 35(3):536-41.

- ↑ Andre, S. E., et al. (2008). Effect of temperature on host response to Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis infection in the mountain yellow-legged frog (Rana muscosa). Journal of Wildlife Diseases 44(3):716-20.

- 1 2 Rachowicz, L. J. and V. T. Vredenburg. (2004). Transmission of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis within and between amphibian life stages. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 61:75-83.

- ↑ Rachowicz, L. J., et al. (2006). Emerging infectious disease as a proximate cause of amphibian mass mortality. Ecology 87(7), 1671-83.

- ↑ Rollins-Smith, L. A., et al. (2006). Antimicrobial peptide defenses of the mountain yellow-legged frog (Rana muscosa). Developmental & Comparative Immunology 30(9):831-42.

- ↑ Mountain Yellow-legged Frog Hopping for Survival. San Diego Zoo Global.

- 1 2 3 SoCal Wild.com: "Building a Mountain Frogtown for Yellow-Legged Frogs"; Brenda Rees, editor; 10 August 2015.

Further reading

- Adams, M. J., et al. (2005). Distribution patterns of lentic-breeding amphibians in relation to ultraviolet radiation exposure in western North America. Ecosystems 8(5):488-500.

- Bridges, C. M. and M. D. Boone. (2003). The interactive effects of UV-B and insecticide exposure on tadpole survival, growth and development. Biological Conservation 113(1):49-54.

- Briggs, C. J., et al. (2005). Investigating the population-level effects of chytridiomycosis: an emerging infectious disease of amphibians. Ecology 86(12):3149-59.

- Funk, W. C. and W. W. Dunlap. (1999). Colonization of high-elevation lakes by long-toed salamanders (Ambystoma macrodactylum) after the extinction of introduced trout populations. Canadian Journal of Zoology 77(11):1759-67. (abstract)

- Hillis, D. M. and T. P. Wilcox. (2005). Phylogeny of the New World true frogs (Rana). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 34(2):299-314.

- Hillis, D. M. (2007). Constraints in naming parts of the Tree of Life. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 42(2):331-38.

- Knapp, R. A. and K. R. Matthews. (2000). Non-native fish introductions and the decline of the mountain yellow-legged frog from within protected areas. Conservation Biology 14(2), 428-38.

- Pister, E. P. (2001). Wilderness fish stocking: history and perspective. Ecosystems 4(4):279-86.

- Stuart, S. N., et al. (2004). Status and trends of amphibian declines and extinctions worldwide. Science 306(5702):1783-86.

- Vredenburg, V. T., et al. (2007). Concordant molecular and phenotypic data delineate new taxonomy and conservation priorities for the endangered mountain yellow-legged frog (Ranidae: Rana muscosa). Journal of Zoology 271:361-74.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rana muscosa (Mountain yellow-legged frog). |

![]() Data related to Rana muscosa at Wikispecies

Data related to Rana muscosa at Wikispecies

- Fisher, R. N. and T. J. Case. (2003). Rana muscosa, A Field Guide to the Reptiles and Amphibians of Coastal Southern California. USGS.

- Range Map: R. muscosa vs. R. sierrae, California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

- The Mountain Yellow-legged Frog Site.

- Rana muscosa, AmphibiaWeb.

- Rana muscosa vocalizations, Western Soundscape Archive.