Monongahela River

| Monongahela River | |

The Monongahela River in Pittsburgh passing the South Side on the right and Uptown/The Bluff on the left just before entering Downtown Pittsburgh | |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| States | Pennsylvania, West Virginia |

| Counties | Marion WV, Monongalia WV, Greene PA, Fayette PA, Washington PA, Westmoreland PA, Allegheny PA |

| Tributaries | |

| - left | Peters Creek, Streets Run, Becks Run |

| - right | Cheat River, Youghiogheny River, Turtle Creek |

| Source | Tygart Valley River |

| - location | Pocahontas County, West Virginia |

| - elevation | 4,540 ft (1,384 m) [1] |

| - coordinates | 38°28′06″N 79°58′51″W / 38.46833°N 79.98083°W [2] |

| Secondary source | West Fork River |

| - location | Upshur County, West Virginia |

| - elevation | 1,309 ft (399 m) [3] |

| - coordinates | 38°51′08″N 80°21′32″W / 38.85222°N 80.35889°W [4] |

| Source confluence | |

| - location | Fairmont, West Virginia |

| - elevation | 863 ft (263 m) [4] |

| - coordinates | 39°27′53″N 80°09′10″W / 39.46472°N 80.15278°W [5] |

| Mouth | Ohio River |

| - location | Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania |

| - elevation | 709 ft (216 m) [5] |

| - coordinates | 40°26′30″N 80°00′58″W / 40.44167°N 80.01611°WCoordinates: 40°26′30″N 80°00′58″W / 40.44167°N 80.01611°W [5] |

| Length | 130 mi (209 km) [6] |

| Basin | 7,340 sq mi (19,011 km2) [7] |

| Discharge | for Braddock, PA |

| - average | 12,650 cu ft/s (358 m3/s) [8] |

| - max | 81,100 cu ft/s (2,296 m3/s) |

| - min | 2,900 cu ft/s (82 m3/s) |

| Discharge elsewhere (average) | |

| - Masontown, PA | 8,433 cu ft/s (239 m3/s) [9] |

Map of the Monongahela River basin, with the Monongahela River highlighted

| |

The Monongahela River (/məˌnɒnɡəˈhiːlə/[10]) — often referred to locally as the Mon /ˈmɒn/ — is a 130-mile-long (210 km)[6] river on the Allegheny Plateau in north-central West Virginia and southwestern Pennsylvania. The Monongahela joins the Allegheny River to form the Ohio River at Pittsburgh.

Etymology

The Native American word Monongahela means "falling banks", in reference to the geological instability of the river's banks. Moravian missionary David Zeisberger (1721–1808) gave this account of the naming: "In the Indian tongue the name of this river was Mechmenawungihilla (alternatively spelled Menawngihella), which signifies a high bank, which is ever washed out and therefore collapses."[11]

The Lenape Language Project renders the word as Mënaonkihëla (pronounced [mənaoŋɡihəla]), translated "where banks cave in or erode",[12] from the verbs mënaonkihële "the dirt caves off" (such as the bank of a river or creek, or in a landslide)[13] and mënaonke (pronounced [mənaoŋɡe]), "it has a loose bank" (where one might fall in).[14]

Monongalia County and the town of Monongah, both in West Virginia, are named for the river, as is Monongahela in Pennsylvania. (The name "Monongalia" is either a Latinized adaptation of "Monongahela" or simply a variant spelling.)

Variant names

According to the Geographic Names Information System, the Monongahela River has also been known historically as:[5]

|

|

|

|

Geography

The Monongahela is formed by the confluence of the West Fork River and its "East Fork" — the Tygart Valley River — at Fairmont, West Virginia. The river is navigable its entire length with a series of locks and dams that maintain a minimum depth of 9 feet (2.7 m) to accommodate coal-laden barges. In Pennsylvania, the Monongahela is met by two major tributaries: the Cheat River, which joins at Point Marion, and the Youghiogheny River, which joins at McKeesport.

The upper drainage area of the river basin is renowned for its whitewater kayaking (and in some cases rafting) opportunities. The land here is of a very rugged plateau type which allows streams to gather sufficient water volume before they fall off the plateau and create challenging rapids. Some of the best known specific stream locations for this include:

- Youghiogheny River at Ohiopyle, PA[16]

- Youghiogheny River at Friendsville, MD[17]

- Cheat River at Albright, WV[18][19]

- Tygart River at Belington, WV[20][21][22]

History

Ice Age

During the period of the Wisconsinan glaciation (ca. 110,000 to 10,000 years ago), what is now called the Monongahela flowed north across present-day Pennsylvania and into the Saint Lawrence River watershed. An ice dam created a vast lake — known as Lake Monongahela — stretching from its outlet at present-day Beaver, Pennsylvania for 200 miles (320 km) south to at least Weston, West Virginia. It was as much as 100 miles wide (160 km) at its maximum, and its surface rose at times to 1,100 feet (340 m) above sea level. Hundreds of feet deep (~100 m) in places, its western and southern overflow gradually created the present-day upper Ohio River Valley.[23]

18th and 19th centuries

The Monongahela River valley was the site of a famous, if small, battle that was one of the first in the French and Indian War — the Braddock Expedition (May–July 1755). It resulted in a sharp defeat for British and Colonial forces against those of the French and their Native American allies.

In 1817, the Pennsylvania legislature authorized the Monongahela Navigation Company to build 16 dams with bypass locks to create a river transportation system between Pittsburgh and the area that would later become West Virginia.[24] Originally planned to run as far south as the Cheat River, the system was extended to Fairmont, and bituminous coal from West Virginia was the chief product transported downstream. After a canal tunnel through Grant's Hill in Pittsburgh was completed in 1832, boats could travel between the Monongahela River and the Western Division Canal of Pennsylvania's principal east-west canal and railroad system, the Main Line of Public Works. In 1897, the federal government took possession of the Monongahela Navigation through condemnation proceedings. Later, the dam-lock combinations were increased in size and reduced in number.[25] In 2006, the navigation system, operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, had nine dam-locks along 128.7 miles (207.1 km) of waterway.[26] The locks overcame a change in elevation of about 147 feet (44.8 m).[25]

Briefly linked to the Monongahela Navigation was the Youghiogheny Navigation, a slack water system of 18.5 miles (29.8 km) between McKeesport and West Newton. It had two dam-locks overcoming a change in elevation of about 27 feet (8.2 m). Opening in 1850, it was destroyed by a flood in 1865.[25]

During the 19th century, the Monongahela was heavily used by industry, and several U.S. Steel plants, including the Homestead Works, site of the Homestead Strike of 1892, were built along its banks. Following the killing of several workers in the course of the strike, anarchist Emma Goldman wrote: "Words had lost their meaning in the face of the innocent blood spilled on the banks of the Monongahela."

20th century

Three ships in the United States Navy have been named Monongahela after the river. In the 1930s, severe drought caused the river to run dry.

The river was the site of a famous airplane crash that has become the subject of numerous urban legends and conspiracy theories. Early in the morning of January 31, 1956, a B-25 bomber en route from Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada to Olmsted Air Force Base in Pennsylvania crashed into the river near the Glenwood Bridge in Homestead, Pennsylvania. All six crewmen survived the crash, but two later succumbed to exposure and drowned. Despite the relative shallowness of the water, the aircraft was never recovered.[27][28] The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette published a graphical representation of the flight path and flight details in 1999.[29][30]

Monongy

Legend has it that Monongy, the man-fish, lives in the river. There are records that go as far back as the French and Indian War (1754-1763) that describe encounters between British soldiers and strange aquatic creatures.[31] The local Indian tribes referred to this creature as "Monongy". There was even a Monongy craze in the early 1930s through the late 1950s. Sightings occurred on a weekly basis and the police department created a task force whose sole purpose was to investigate sightings of the creature. No evidence was ever produced to lend credence to the claims until May 12, 2003, when a privately owned fishing vessel was the first to take photos of the creature. The photos were available online for a short time until they were inexplicably taken down. Speculation persists that the government has procured the photographs and are covering up the existence of Monongy. Crypto-zoologists from around the world still visit the Monongahela every year to catch a glimpse of the elusive water beast.[32]

Gallery

-

The South Tenth Street Bridge over the Monongahela River in Pittsburgh in 2005

-

The Monongahela River in Fairmont, West Virginia in 2006

-

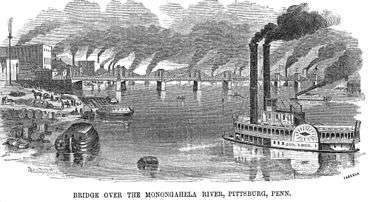

Monongahela River Scene, 1857[1]

-

Opekiska Lock and Dam on the Monongahela River near Fairmont, West Virginia at river mile 115 (185 km)

- ^ Ballou's Pictorial, issue of 21 Feb 1857

See also

- List of crossings of the Monongahela River

- List of rivers of Pennsylvania

- List of rivers of West Virginia

- Geography of Pennsylvania

Notes and references

- ↑ Google Earth elevation for GNIS source coordinates. Retrieved on March 12, 2007.

- ↑ Geographic Names Information System. "Geographic Names Information System entry for Tygart Valley River (Feature ID #1553309)". Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- ↑ Geographic Names Information System. "Geographic Names Information System entry for Straight Fork (headwaters tributary of West Fork River) (Feature ID #1547564)". Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- 1 2 Geographic Names Information System. "Geographic Names Information System entry for West Fork River (Feature ID #1548931)". Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- 1 2 3 4 Geographic Names Information System. "Geographic Names Information System entry for Monongahela River (Feature ID #1209053)". Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map, accessed August 15, 2011

- ↑ Gillespie, William H. (2006). "Monongahela River". In Ken Sullivan (ed.). The West Virginia Encyclopedia. Charleston, W.Va.: West Virginia Humanities Council. p. 492. ISBN 0-9778498-0-5.

- ↑ United States Geological Survey; USGS 03085000 Monongahela River at Braddock, PA; retrieved Sep 29, 2010.

- ↑ United States Geological Survey; USGS 03072655 Monongahela River near Masontown, PA; retrieved September 29, 2010.

- ↑ There are several ways to pronounce this word that are acceptable. From "Geographical Names" of Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition (2009): /məˌnɒnɡəˈhiːlə/, /məˌnɒŋɡəˈhiːlə/ or /məˌnɒŋɡəˈheɪlə/.

- ↑ Zeisberger, David, David Zeisberger's History of the Northern American Indians in 18th Century Ohio, New York and Pennsylvania, pg 43; Wennawoods Publishing, 1999, ISBN 1-889037-17-6

- ↑ "Lenape Talking Dictionary". Retrieved 2010-12-10.

- ↑ "Lenape Talking Dictionary". Retrieved 2010-12-10.

- ↑ "Lenape Talking Dictionary". Retrieved 2010-12-10.

- ↑ John Gilmary Shea. Relations diverses sur la bataille du Malangueulé : gagné le 9 juillet, 1755, par les François sous M. de Beaujeu, commandant du fort du Quesne sur les Anglois sous M. Braddock, général en chef des troupes angloises. Nouvelle York : De la Presse Cramoisy, 1860. OCLC 15760312.

- ↑ https://www.americanwhitewater.org/content/River/detail/id/1687/

- ↑ https://www.americanwhitewater.org/content/River/detail/id/753/

- ↑ https://www.americanwhitewater.org/content/River/detail/id/2346/

- ↑ https://www.americanwhitewater.org/content/River/detail/id/2347/

- ↑ https://www.americanwhitewater.org/content/River/detail/id/2451/

- ↑ https://www.americanwhitewater.org/content/River/detail/id/2452/

- ↑ https://www.americanwhitewater.org/content/River/detail/id/2453/

- ↑ Garton, E. Ray (2012). "Fauna of the Ice Age". Wonderful West Virginia. p. 11 (January issue).

- ↑ Monongahela Navigation Company Copybook, 1840-1897, DAR.1937.41, The Darlington Collection, Special Collections Department, University of Pittsburgh

- 1 2 3 Shank, William H. (1986). The Amazing Pennsylvania Canals, 150th Anniversary Edition. York, Pennsylvania: American Canal and Transportation Center. p. 76. ISBN 0-933788-37-1.

- ↑ "Navigation". U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. 2006. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- ↑ Powell, Albrecht. "The Pittsburgh B-25 Ghost Bomber Mystery (1956)". About.com. Retrieved 2016-02-13.

- ↑ Ove, Torsten (4 April 1999). "Searchers say 'Ghost Bomber' can be found in the Mon". Retrieved 2016-02-13.

- ↑ James Hilston, Post-Gazette Staff Artist. "PG Graphic: One of the Mysteries of Pittsburgh: The B-25 in the Mon". Retrieved 2016-02-13.

- ↑ "Let’s learn from the past: B-25 ‘Ghost Bomber’". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 2016-02-13.

- ↑ Bill Eggert. "Mon Monster Mystery Endures"

- ↑ http://www.post-gazette.com/life/lifestyle/2010/07/12/52-take-a-swim-in-tepid-Allegheny/stories/201007120196

Bibliography

- Bissell, Richard (1952), The Monongahela, Rinehart & Co.

- Callahan, James Morton and Bernard Lee Butcher (1912), Genealogical and Personal History of the Upper Monongahela Valley, West Virginia, New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company.

- Core, Earl L. (1984), "The Monongalia River," in: Bartlett, Richard A. (ed), Rolling Rivers: An Encyclopedia of America's Rivers. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-003910-0. pp 149–52.

- Core, Earl L. (1974–84), The Monongalia Story: A Bicentennial History, Parsons, W.Va.: McClain Printing Co., 5 volumes; an extensive, well-documented natural & human history of the Monongahela River basin.

- Volume I: Prelude (1974)

- Volume II: The Pioneers (1976)

- Volume III: Discord (1979)

- Volume IV: Industrialization (1984)

- Volume V: Sophistication (1984)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Monongahela River. |

- U.S. Geological Survey: PA stream gaging stations

Beach, Chandler B., ed. (1914). "Monongahela". The New Student's Reference Work. Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.

Beach, Chandler B., ed. (1914). "Monongahela". The New Student's Reference Work. Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.

|