Communist Party of India

The Communist Party of India (CPI) (Bhāratīya Kamyunisṭ Pārṭī) is a communist party in India. In the Indian Communist movement, there are different views on exactly when the Communist Party of India was founded. But the date maintained as the foundation day by the CPI is 26 December 1925.[2] However, the Communist Party of India (Marxist), which separated from the CPI, has a different version that it was founded in 1925.

Communism during the colonial period

The Communist Party of India has officially stated that it was formed on 25 December 1925 at the first Kanpur Party Conference. But as per the version of CPI(M), the Communist Party of India was founded in Tashkent, Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic on 17 October 1920, soon after the Second Congress of the Communist International. The founding members of the party were M.N. Roy, Evelyn Trent Roy (Roy's wife), Abani Mukherji, Rosa Fitingof (Abani's wife), Mohammad Ali (Ahmed Hasan), Mohammad Shafiq Siddiqui, Rafiq Ahmed of Bhopal and M.P.B.T. Aacharya, and Sultan Ahmed Khan Tarin of North-West Frontier Province.[3][4][5] The CPI says that there were many communist groups formed by Indians with the help of foreigners in different parts of the world and the Tashkent group was only one of. contacts with Anushilan and Jugantar groups in Bengal. Small communist groups were formed in Bengal (led by Muzaffar Ahmed), Bombay (led by S.A. Dange), Madras (led by Singaravelu Chettiar), United Provinces (led by Shaukat Usmani) and Punjab and Sindh(led by Ghulam Hussain). However, only Usmani became a CPI party member.[6]

During the 1920s and the early 1930s the party was badly organised, and in practice there were several communist groups working with limited national coordination. The British colonial authorities had banned all communist activity, which made the task of building a united party very difficult. Between 1921 and 1924 there were three conspiracy trials against the communist movement; First Peshawar Conspiracy Case, Meerut Conspiracy Case and the Cawnpore Bolshevik Conspiracy Case. In the first three cases, Russian-trained muhajir communists were put on trial. However, the Cawnpore trial had more political impact. On 17 March 1924, M.N. Roy, S.A. Dange, Muzaffar Ahmed, Nalini Gupta, Shaukat Usmani, Singaravelu Chettiar, Ghulam Hussain and R.C. Sharma were charged, in Cawnpore (now spelt Kanpur) Bolshevik Conspiracy case. The specific pip charge was that they as communists were seeking "to deprive the King Emperor of his sovereignty of British India, by complete separation of India from imperialistic Britain by a violent revolution." Pages of newspapers daily splashed sensational communist plans and people for the first time learned, on such a large scale, about communism and its doctrines and the aims of the Communist International in India.[7]

Singaravelu Chettiar was released on account of illness. M.N. Roy was in Germany and R.C. Sharma in French Pondichéry, and therefore could not be arrested. Ghulam Hussain confessed that he had received money from the Russians in Kabul and was pardoned. Muzaffar Ahmed, Nalini Gupta, Shaukat Usmani and Dange were sentenced for various terms of imprisonment. This case was responsible for actively introducing communism to a larger Indian audience.[7] Dange was released from prison in 1927.

On 25 December 1925 a communist conference was organised in Kanpur. Colonial authorities estimated that 500 persons took part in the conference. The conference was convened by a man called Satyabhakta. At the conference Satyabhakta argued for a 'National communism' and against subordination under Comintern. Being outvoted by the other delegates, Satyabhakta left both the conference venue in protest. The conference adopted the name 'Communist Party of India'. Groups such as Labour Kisan Party of Hindustan (LKPH) dissolved into the unified CPI.[8] The émigré CPI, which probably had little organic character anyway, was effectively substituted by the organisation now operating inside India.

Soon after the 1926 conference of the Workers and Peasants Party of Bengal, the underground CPI directed its members to join the provincial Workers and Peasants Parties. All open communist activities were carried out through Workers and Peasants Parties.[9]

The sixth congress of the Communist International met in 1928. In 1927 the Kuomintang had turned on the Chinese communists, which led to a review of the policy on forming alliances with the national bourgeoisie in the colonial countries. The Colonial theses of the 6th Comintern congress called upon the Indian communists to combat the 'national-reformist leaders' and to 'unmask the national reformism of the Indian National Congress and oppose all phrases of the Swarajists, Gandhists, etc. about passive resistance'.[10] The congress did however differentiate between the character of the Chinese Kuomintang and the Indian Swarajist Party, considering the latter as neither a reliable ally nor a direct enemy. The congress called on the Indian communists to utilize the contradictions between the national bourgeoisie and the British imperialists.[11] The congress also denounced the WPP. The Tenth Plenum of the Executive Committee of the Communist International, 3 July 1929 – 19 July 1929, directed the Indian communists to break with WPP. When the communists deserted it, the WPP fell apart.[12]

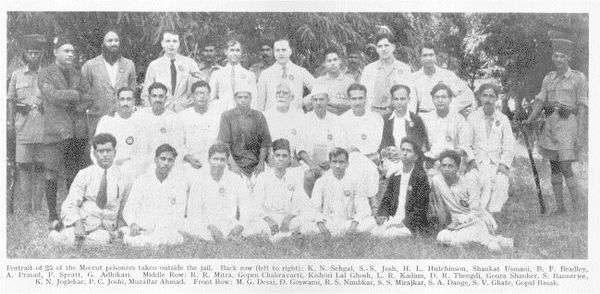

On 20 March 1929, arrests against WPP, CPI and other labour leaders were made in several parts of India, in what became known as the Meerut Conspiracy Case. The communist leadership was now put behind bars. The trial proceedings were to last for four years.[13][14]

As of 1934, the main centres of activity of CPI were Bombay, Calcutta and Punjab. The party had also begun extending its activities to Madras. A group of Andhra and Tamil students, amongst them P. Sundarayya, were recruited to the CPI by Amir Hyder Khan.[15]

The party was reorganised in 1933, after the communist leaders from the Meerut trials were released. A central committee of the party was set up. In 1934 the party was accepted as the Indian section of the Communist International.[16]

When Indian leftwing elements formed the Congress Socialist Party in 1934, the CPI branded it as Social Fascist.[10]

In connection with the change of policy of the Comintern toward Popular Front politics, the Indian communists changed their relation to the Indian National Congress. The communists joined the Congress Socialist Party, which worked as the left wing of Congress. Through joining CSP, the CPI accepted the CSP demand for a Constituent Assembly, which it had denounced two years before. The CPI however analysed that the demand for a Constituent Assembly would not be a substitute for soviets.[17]

In July 1937, the first Kerala unit of CPI was founded at a clandestine meeting in Calicut. Five persons were present at the meeting, P. Krishna Pillai E.M.S. Namboodiripad, N.C. Sekhar, K. Damodaran and S.V. Ghate. The first four were members of the CSP in Kerala. The latter, Ghate, was a CPI Central Committee member, who had arrived from Madras.[18] Contacts between the CSP in Kerala and the CPI had begun in 1935, when P. Sundarayya (CC member of CPI, based in Madras at the time) met with EMS and Krishna Pillai. Sundarayya and Ghate visited Kerala at several times and met with the CSP leaders there. The contacts were facilitated through the national meetings of the Congress, CSP and All India Kisan Sabha.[15]

In 1936–1937, the cooperation between socialists and communists reached its peak. At the 2nd congress of the CSP, held in Meerut in January 1936, a thesis was adopted which declared that there was a need to build 'a united Indian Socialist Party based on Marxism-Leninism'.[19] At the 3rd CSP congress, held in Faizpur, several communists were included into the CSP National Executive Committee.[20]

In Kerala communists won control over CSP, and for a brief period controlled Congress there.

Two communists, E.M.S. Namboodiripad and Z.A. Ahmed, became All India joint secretaries of CSP. The CPI also had two other members inside the CSP executive.[17]

On the occasion of the 1940 Ramgarh Congress Conference CPI released a declaration called Proletarian Path, which sought to utilise the weakened state of the British Empire in the time of war and gave a call for general strike, no-tax, no-rent policies and mobilising for an armed revolutionary uprising. The National Executive of the CSP assembled at Ramgarh took a decision that all communists were expelled from CSP.[21]

Communists strengthened their control over the All India Trade Union Congress. At the same time, communists were politically cornered for their opposition to the Quit India Movement.

CPI contested the Provincial Legislative Assembly elections of 1946 of its own. It had candidates in 108 out of 1585 seats. It won in eight seats. In total the CPI vote counted 666 723, which should be seen with the backdrop that 86% of the adult population of India lacked voting rights. The party had contested three seats in Bengal, and won all of them. One CPI candidate, Somanth Lahiri, was elected to the Constituent Assembly.[22]

| Communist parties |

|---|

|

|

Asia

|

|

Europe

|

|

Oceania

|

|

Related topics |

Communists after independence

During the period around and directly following Independence in 1947, the internal situation in the party was chaotic. The party shifted rapidly between left-wing and right-wing positions. In February 1948, at the 2nd Party Congress in Calcutta, B.T. Ranadive (BTR) was elected General Secretary of the party.[23] The conference adopted the 'Programme of Democratic Revolution'. This programme included the first mention of struggle against caste injustice in a CPI document.[24]

In several areas the party led armed struggles against a series of local monarchs that were reluctant to give up their power. Such insurgencies took place in Tripura, Telangana and Kerala. The most important rebellion took place in Telangana, against the Nizam of Hyderabad. The Communists built up a people's army and militia and controlled an area with a population of three million. The rebellion was brutally crushed and the party abandoned the policy of armed struggle. BTR was deposed and denounced as a 'left adventurist'.

In Manipur, the party became a force to reckon with through the agrarian struggles led by Jananeta Irawat Singh. Singh had joined CPI in 1946.[25] At the 1951 congress of the party, 'People's Democracy' was substituted by 'National Democracy' as the main slogan of the party.[26]

Communist Party was founded in Bihar in 1939. Post independence, communist party achieved success in Bihar (Bihar and Jharkhand). Communist party conducted movements for land reform, trade union movement was at its peak in Bihar in the sixties, seventies and eighties. Achievement of communists in Bihar placed the communist party in the forefront of left movement in India. Bihar produced some of the legendary leaders like Kishan leaders Sahjanand Saraswati and Karyanand Sharma, intellectual giants like Jagannath Sarkar, Yogendra Sharma and Indradeep Sinha, mass leaders like Chandrashekhar Singh and Sunil Mukherjee, Trade Union leaders like Kedar Das and others. It was in Bihar that JP's total revolution was exposed and communist party under the leadership of Jagannath Sarkar fought Total Revolution and exposed its hollowness. "Many Streams" Selected Essays by Jagannath Sarkar and Reminiscing Sketches, Compiled by Gautam Sarkar, Edited by Mitali Sarkar, First Published : May 2010, Navakaranataka Publications Pvt. Ltd., Bangalore

In early 1950s young communist leadership was uniting textile workers, bank employees and unorganized sector workers to ensure mass support in north India. National leaders like S A Dange, Chandra Rajeswara Rao and P K Vasudevan Nair were encouraging them and supporting the idea despite their differences on the execution. Firebrand Communist leaders like Homi F Dazi, Guru Radha Kishan, H L Parwana, Sarjoo Pandey, Darshan Singh Canadian and Avtaar Singh Malhotra were emerging between the masses and the working class in particular. This was the first leadership of communists that was very close to the masses and people consider them champions of the cause of the workers and the poor. In Delhi, May Day (majdoor diwas or mai diwas) was organised at Chandni Chowk Ghantaghar in such a manner that demonstrates the unity between all the factions of working classes and ignite the passion for communist movement in the northern part of India.

In 1952, CPI became the first leading opposition party in the Lok Sabha, while the Indian National Congress was in power. (Note - At this time, there was no CPI(M) and both were united)

Communist movement or CPI in particular emerged as a front runner after Guru Radha Kishan undertook a fast unto death for 24 days to promote the cause of textile workers in Delhi. Till than it was a public misconception that communists are the revolutionaries with arms in their hands and workers and their families were afraid to get associated with the communists but this act mobilise general public in the favour communist movement as a whole. During this period people with their families use to visit this 'dharna sthal' to encourage CPI cadre.

This model of selflessness for the society benefits worked for CPI far more than expected. This trend was followed by almost all other state units of party in Hindi heartland. Communist Party related trade union AITUC became a prominent force to unite the workers in textile, municipal and unorganised sectors, the first labour union in unorganised sector was also emerged in the leadership of Comrade Guru Radha Kishan during this period in Delhi's Sadar Bazaar area. This movement of mass polarisation of workers in the favour of CPI worked effectively in Delhi and paved the way for great success of CPI in the elections in working class dominated areas in Delhi. Comrade Gangadhar Adhikari and E.M.S. Namboodiripad applauded this brigade of dynamic comrades for their selfless approach and organisational capabilities. This brigade of firebrand communists gained more prominence when Telangana Hero Chandra Rajeswara Rao raised as General Secretary of Communist Party of India.

In the Travancore-Cochin Legislative Assembly election, 1952, Communist Party was banned, so couldn't took part in the election process.[27] In the general elections in 1957, the CPI emerged as the largest opposition party. In 1957, the CPI won the state elections in Kerala. This was the first time that an opposition party won control over an Indian state. E. M. S. Namboodiripad became Chief Minister. At the 1957 international meeting of Communist parties in Moscow, the Communist Party of China directed criticism at the CPI for having formed a ministry in Kerala.[28]

Supporting China in Sino-Indian War

During the Sino-Indian War,official policy of Communists was to support the Chinese Government, while few sections of the party revolted against this stand.[29] There were three factions in the party – "internationalists", "centrists", and "nationalists". "Internationalists", including B. T. Ranadive, P. Sundarayya, P. C. Joshi, Makineni Basavapunnaiah, Jyoti Basu, and Harkishan Singh Surjeet, supported the Chinese stand. The "nationalists", including prominent leaders such as S.A. Dange, A. K. Gopalan backed India. "Centrists" took a neutral view; Ajoy Ghosh was the prominent person in the centrist faction. In general, most of Bengal Communist leaders supported China and most others supported India.[30] Hundreds of CPI leaders, accused of being pro-Chinese, were imprisoned. Some of the nationalists were also imprisoned, as they used to express their opinion only in party forums, and CPI's official stand was pro-China.

Ideological differences lead to the split in the party in 1964 when two different party conferences were held, one of CPI and one of the Communist Party of India (Marxist). There is a common misconception that the rift during Sino-Indian war lead to the 1962 split. In fact, the split was leftists vs rightists, rather than internationalists vs nationalists. The presence of nationalists, and internationalists P. Sundarayya, Jyoti Basu, and Harkishan Singh Surjeet in the Communist Party of India (Marxist) proves this fact.

During the period 1970–77, CPI was allied with the Congress party. In Kerala, they formed a government together with Congress, with the CPI-leader C. Achutha Menon as Chief Minister. After the fall of the regime of Indira Gandhi, CPI reoriented itself towards cooperation with CPI(M).

In 1986, the CPI's leader in the Punjab and MLA in the Punjabi legislature Darshan Singh Canadian was assassinated by Sikh extremists. Then on 19 May 1987, Deepak Dhawan, General Secretary of Punjab CPI(M), was murdered. Altogether about 200 communist leaders out of which most were Sikhs were killed by Sikh extremists in Punjab.

Present situation

CPI was recognised by the Election Commission of India as a 'National Party'. To date, CPI happens to be the only national political party from India to have contested all the general elections using the same electoral symbol. However, after the 2014 General Elections, CPI lost its status as a national party owing to its inability to poll the bare minimum votes or win the minimum number of seats required for the purpose.

On the national level they supported the Indian National Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government, but without taking part in it. The party is part of a coalition of leftist and communist parties known in the national media as the Left Front. Upon attaining power in May 2004, the United Progressive Alliance formulated a programme of action known as the Common Minimum Programme. The Left bases its support to the UPA on strict adherence to it. Provisions of the CMP mentions to discontinue disinvestment, massive social sector outlays and an independent foreign policy.

On 8 July 2008, Prakash Karat announced that the Left Front was withdrawing its support over the decision by the government to go ahead with the United States-India Peaceful Atomic Energy Cooperation Act. The Left Front had been a staunch advocate of not proceeding with this deal citing national interests.[31]

In West Bengal it participates in the Left Front. It also participated in the state government in Manipur. In Kerala the party is part of Left Democratic Front. In Tripura the party is a partner of the governing Left Front, having a minister. In Tamil Nadu it is part of the Progressive Democratic Alliance. It is involved in the Left Democratic Front in Maharashtra

The current general secretary of CPI is S. Sudhakar Reddy.

The principal mass organisations of the CPI are:

- All India Trade Union Congress

- All India Youth Federation

- All India Students Federation

- National Federation of Indian Women

- All India Kisan Sabha (peasants organisation)

- Bharatiya Khet Mazdoor Union (agricultural workers)

- All India State Government Employees Federation (State government employees)

Notable leaders

- N.E. Balaram - Founding leader of the communist movement in Kerala, India

- M. N. Govindan Nair(MN) – Kerala state general secretary during the first communist ministry and a freedom fighter

- C. Achutha Menon – Finance minister in first Kerala ministry later chief minister

- T. V. Thomas – Minister in first Kerala ministry

- M. Kalyanasundaram – Tamil Nadu

- P. K. Vasudevan Nair – Chief minister in Kerala

- Indrajit Gupta – Parliamentarian, former general secretary and a former central minister

- Yogendra Sharma - M.P,Lok Sabha,Rajya Sabha,Leader All India Kisan Sabha,Intellectual

- Bhupesh Gupta – Parliamentarian

- Ajoy Ghosh – Last general secretary of unified CPI, freedom fighter

- Chandra Rajeswara Rao – former general secretary, Telangana freedom fighter

- Jagannath Sarkar – former National Secretary, freedom fighter, builder of communist movement in Bihar and Jharkhand

- Geeta Mukherjee - Former President of National Federation of Indian Women

- Ardhendu Bhushan Bardhan – former general secretary

- Chaturanan Mishra parliamentarian & former Central Minister of India

- Shashikant Chowdhary Member of State control commission & Bihar state council, CPI. Also was in different central management committees like National Research center for cashew & Research advisory board. DK, Mangalore.

- Suravaram Sudhakar Reddy – current general secretary of the party

- D. Raja – parliamentarian & secretary of the party

- Shripad Amrit Dange – Freedom fighter & former chairman of the party

- Hijam Irabot – Founder leader of CPI in Manipur

- P. S. Sreenivasan – Former minister of Kerala

- C. K. Chandrappan – Parliamentarian & former Kerala state secretary of the party

- Pannyan Raveendran – Former Kerala state secretary of the party

- Kanam Rajendran – Current Kerala state secretary of the party

- Nallakannu – Parliamentarian & former Tamil Nadu state secretary of the party

- D. Pandian-Parliamentarian & former Tamil Nadu state secretary

- Binoy Viswam – Former minister in the Government of Kerala

- Thoppil Bhasi – Writer, film director & parliamentarian

- Puran Chand Joshi – first general secretary of the Communist Party of India

- Veliyam Bharghavan – Parliamentarian & Former Kerala state secretary of the party

- E. Chandrasekharan Nair – Senior leader and Former Minister in the Government of Kerala

- Ramendra Kumar – Former Parliamentarian, national executive member, national president AITUC

- Meghraj Tawar – Udaipur district secretary

- Govind Pansare – Prominent activist and lawyer

Lok Sabha election tally

| Lok Sabha | Lok Sabha constituencies |

Seats Contested |

Won | Net Change in seats |

Votes | Votes % | Change in vote % |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 489 | 49 | 16 | - | 34,87,401 | 3.29% | - | [32] |

| Second | 494 | 109 | 27 | | 1,07,54,075 | 8.92% | |

[33] |

| Third | 494 | 137 | 29 | | 1,14,50,037 | 9.94% | |

[34] |

| Fourth | 520 | 109 | 23 | | 74,58,396 | 5.11% | |

[35] |

| Fifth | 518 | 87 | 23 | | 69,33,627 | 4.73% | |

[36] |

| Sixth | 542 | 91 | 7 | | 53,22,088 | 2.82% | |

[37] |

| Seventh | 529 ( 542* ) | 47 | 10 | | 49,27,342 | 2.49% | |

[38] |

| Eighth | 541 | 66 | 6 | | 67,33,117 | 2.70% | |

[39][40] |

| Ninth | 529 | 50 | 12 | | 77,34,697 | 2.57% | |

[41] |

| Tenth | 534 | 43 | 14 | | 68,98,340 | 2.48% | |

[42][43] |

| Eleventh | 543 | 43 | 12 | | 65,82,263 | 1.97% | |

[44] |

| Twelfth | 543 | 58 | 09 | | 64,29,569 | 1.75% | |

[45] |

| Thirteenth | 543 | 54 | 04 | | 53,95,119 | 1.48% | |

[46] |

| Fourteenth | 543 | 34 | 10 | | 54,84,111 | 1.41% | |

[47] |

| Fifteenth | 543 | 56 | 04 | | 59,51,888 | 1.43% | |

[48] |

| Sixteenth | 543 | 67 | 01 | | 4327298 | 0.78% | |

[49] |

* : 12 seats in Assam and 1 in Meghalaya did not vote.[50]

| State | No. of candidates 2004 | No. of elected 2004 | No. of candidates 1999 | No. of elected 1999 | Total no. of seats in the state |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 42 |

| Arunachal Pradesh | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Assam | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 14 |

| Bihar | 6 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 40 (2004)/54(1999) |

| Chhattisgarh | 1 | 0 | - | - | 11 (2004) |

| Goa | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Gujarat | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 26 |

| Haryana | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Jammu and Kashmir | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Jharkhand | 1 | 1 | - | - | 14 (2004) |

| Karnataka | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 |

| Kerala | 4 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 20 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 29 (2004)/40(1999) |

| Maharashtra | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 48 |

| Manipur | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Meghalaya | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Mizoram | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Nagaland | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Odisha | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 21 |

| Punjab | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| Rajasthan | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 25 |

| Sikkim | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Tamil Nadu | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 39 |

| Tripura | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 6 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 80 (2004)/85 (1999) |

| Uttarakhand | 0 | 0 | - | - | 5 (2004) |

| West Bengal | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 42 |

| Union Territories: | |||||

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Chandigarh | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Dadra and Nagar Haveli | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Daman and Diu | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Delhi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Lakshadweep | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Puducherry | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total: | 34 | 10 | 54 | 4 | 543 |

State election results

| State | No. of candidates | No. of elected | Total no. of seats in Assembly | Year of Election |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andhra Pradesh | 12 | 6 | 294 | 2004 |

| Assam | 19 | 1 | 126 | 2001 |

| Bihar | 153 | 5 | 324 | 2000 |

| Chhattisgarh | 18 | 0 | 90 | 2003 |

| Delhi | 2 | 0 | 70 | 2003 |

| Goa | 3 | 0 | 40 | 2002 |

| Gujarat | 1 | 0 | 181 | 2002 |

| Haryana | 10 | 0 | 90 | 2000 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 7 | 0 | 68 | 2003 |

| Jammu and Kashmir | 5 | 0 | 87 | 2002 |

| Karnataka | 5 | 0 | 224 | 2004 |

| Kerala | 22 | 17 | 140 | 2006 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 17 | 0 | 230 | 2003 |

| Maharashtra | 19 | 0 | 288 | 1999 |

| Manipur | 16 | 4 | 60 | 2006 |

| Meghalaya | 3 | 0 | 60 | 2003 |

| Mizoram | 4 | 0 | 40 | 2003 |

| Odisha | 6 | 1 | 147 | 2004 |

| Puducherry | 2 | 0 | 30 | 2001 |

| Punjab | 11 | 0 | 117 | 2006 |

| Rajasthan | 15 | 0 | 200 | 2003 |

| Tamil Nadu | 8 | 6 | 234 | 2006 |

| Tripura | 2 | 1 | 60 | 2003 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 5 | 0 | 402 | 2002 |

| Uttarakhand | 14 | 0 | 70 | 2002 |

| West Bengal | 13 | 8 | 294 | 2006 |

Results from the Election Commission of India website. Results do not deal with partitions of states (Bihar was bifurcated after the 2000 election, creating Jharkhand), defections and by-elections during the mandate period.

See also

See also: List of political parties in India, Politics of India, List of communist parties

- Calcutta Thesis

- Communist Ghadar Party of India

- Communist Party of Bangladesh

- Darshan Singh Canadian

- Malayapuram Singaravelu Chettiar

- S A Dange

- Indrajit Gupta

- Guru Radha Kishan

- Azhikodan Raghavan

- Jagannath Sarkar

- Manikuntala Sen

- Pandit Karyanand Sharma

- Chandrashekhar Singh

- Indradeep Sinha

Footnotes

- ↑ "List of Political Parties and Election Symbols main Notification Dated 18.01.2013" (PDF). India: Election Commission of India. 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ↑ https://sites.google.com/a/communistparty.in/cpi/brief-history-of-cpi

- ↑ Later arrested, tried and sentenced to hard labour in the Moscow-Peshawar Conspiracy Case in 1922; see NWFP and Punjab Government Intelligence Reports, Vols 2 and 3, 1921-1931, at the IOR, British Library, London, UK

- ↑ M.V. S. Koteswara Rao. Communist Parties and United Front – Experience in Kerala and West Bengal. Hyderabad: Prajasakti Book House, 2003. p. 88-89

- ↑ Ganguly, Basudev. S.A. Dange – A Living Presence at the Centenary Year in Banerjee, Gopal (ed.) S.A. Dange – A Fruitful Life. Calcutta: Progressive Publishers, 2002. p. 63.

- ↑ M.V. S. Koteswara Rao. Communist Parties and United Front – Experience in Kerala and West Bengal. Hyderabad: Prajasakti Book House, 2003. p. 89

- 1 2 Ralhan, O.P. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Political Parties New Delhi: Anmol Publications p. 336, Rao. p. 89-91

- ↑ M.V. S. Koteswara Rao. Communist Parties and United Front – Experience in Kerala and West Bengal. Hyderabad: Prajasakti Book House, 2003. p. 92-93

- ↑ M.V. S. Koteswara Rao. Communist Parties and United Front – Experience in Kerala and West Bengal. Hyderabad: Prajasakti Book House, 2003. p. 111

- 1 2 Saha, Murari Mohan (ed.), Documents of the Revolutionary Socialist Party: Volume One 1938–1947. Agartala: Lokayata Chetana Bikash Society, 2001. p. 21-25

- ↑ M.V. S. Koteswara Rao. Communist Parties and United Front – Experience in Kerala and West Bengal. Hyderabad: Prajasakti Book House, 2003. p. 47-48

- ↑ M.V. S. Koteswara Rao. Communist Parties and United Front – Experience in Kerala and West Bengal. Hyderabad: Prajasakti Book House, 2003. p. 97-98, 111–112

- ↑ Ralhan, O.P. (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Political Parties – India – Pakistan – Bangladesh – National -Regional – Local. Vol. 23. Revolutionary Movements (1930–1946). New Delhi: Anmol Publications, 2002. p. 689-691

- ↑ M.V. S. Koteswara Rao. Communist Parties and United Front – Experience in Kerala and West Bengal. Hyderabad: Prajasakti Book House, 2003. p. 96

- 1 2 E.M.S. Namboodiripad. The Communist Party in Kerala – Six Decades of Struggle and Advance. New Delhi: National Book Centre, 1994. p. 7

- ↑ Surjeet, Harkishan Surjeet. March of the Communist Movement in India – An Introduction to the Documents of the History of the Communist Movement in India. Calcutta: National Book Agency, 1998. p. 25

- 1 2 Roy, Samaren. M.N. Roy: A Political Biography. Hyderabad: Orient Longman, 1998. p. 113, 115

- ↑ E.M.S. Namboodiripad. The Communist Party in Kerala – Six Decades of Struggle and Advance. New Delhi: National Book Centre, 1994. p. 6

- ↑ E.M.S. Namboodiripad. The Communist Party in Kerala – Six Decades of Struggle and Advance. New Delhi: National Book Centre, 1994. p. 44

- ↑ E.M.S. Namboodiripad. The Communist Party in Kerala – Six Decades of Struggle and Advance. New Delhi: National Book Centre, 1994. p. 45

- ↑ Ralhan, O.P. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Political Parties – India – Pakistan – Bangladesh – National -Regional – Local. Vol. 24. Socialist Movement in India. New Delhi: Anmol Publications, 1997. p. 82

- ↑ M.V. S. Koteswara Rao. Communist Parties and United Front – Experience in Kerala and West Bengal. Hyderabad: Prajasakti Book House, 2003. p. 207.

- ↑ Chandra, Bipan & others (2000). India after Independence 1947–2000, New Delhi:Penguin, ISBN 0-14-027825-7, p.204

- ↑ Microsoft Word – Texte Christop

- ↑ The Telegraph – Calcutta: Northeast

- ↑ E.M.S. Namboodiripad. The Communist Party in Kerala – Six Decades of Struggle and Advance. New Delhi: National Book Centre, 1994. p. 273

- ↑ "History of Kerala Legislature". Government of Kerala. Retrieved July 28, 2015.

- ↑ Basu, Pradip. Towards Naxalbari (1953–1967) – An Account of Inner-Party Ideological Struggle. Calcutta: Progressive Publishers, 2000. p. 32.

- ↑ http://archive.indianexpress.com/news/during-china-war-comrades-cracked-down-on-vs-for-saying-let-s-give-blood-to-jawans/488983/

- ↑ Stern, Robert W. (18 December 2009). "The Sino-Indian Border Controversy and the Communist Party of India". The Journal of Politics 27 (01): 66. doi:10.2307/2128001. JSTOR 2128001 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ http://www.hindu.com/thehindu/holnus/000200807081550.htm

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 1951 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 70. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 1957 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 49. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 1962 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 75. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 1967 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 78. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 1971 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 79. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 1977 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 89. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 1980 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 86. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 1984 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 81. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 1985 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 15. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 1989 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 88. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 1991 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 58. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 1992 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 13. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 1996 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 93. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 1998 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 93. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 1999 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 92. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS Statistical Report : 2004 Vol. 1" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 101. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS 2009 : Performance of National Parties" (PDF). Election Commission of India. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "LS 2014 : List of successful candidates" (PDF). Election Commission of India. p. 93. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Seventh Lok Sabha elections (1980)". Indian Express. Indian Express. March 14, 2014. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

Further reading

Secondary sources

- N.E. Balaram, A Short History of the Communist Party of India. Kozikkode, Cannanore, India: Prabhath Book House, 1967.

- John H. Kautsky, Moscow and the Communist Party of India: A Study in the Postwar Evolution of International Communist Strategy. New York: MIT Press, 1956.

- M.R. Masani, The Communist Party of India: A Short History. New York: Macmillan, 1954.

- Samaren Roy, The Twice-Born Heretic: M.N. Roy and the Comintern. Calcutta: Firma KLM Private, 1986.

- Wendy Singer, "Peasants and the Peoples of the East: Indians and the Rhetoric of the Comintern," in Tim Rees and Andrew Thorpe, International Communism and the Communist International, 1919-43. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998.

Primary sources

- G. Adhikari (ed.), Documents of the History of the Communist Party of India: Volume One, 1917-1922. New Delhi: People's Publishing House, 1971.

- G. Adhikari (ed.), Documents of the History of the Communist Party of India: Volume Two, 1923-1925. New Delhi: People's Publishing House, 1974.

- V.B. Karnick (ed.), Indian Communist Party Documents, 1930-1956. Bombay: Democratic Research Service/Institute of Public Relations, 1957.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Communist Party of India. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Communist Party of India. |