Mobility analogy

The mobility analogy, also called admittance analogy or Firestone analogy, is a method of representing a mechanical system by an analogous electrical system. The advantage of doing this is that there is a large body of theory and analysis techniques concerning complex electrical systems, especially in the field of filters.[1] By converting to an electrical representation, these tools in the electrical domain can be directly applied to a mechanical system without modification. A further advantage occurs in electromechanical systems: Converting the mechanical part of such a system into the electrical domain allows the entire system to be analysed as a unified whole.

The mathematical behaviour of the simulated electrical system is identical to the mathematical behaviour of the represented mechanical system. Each element in the electrical domain has a corresponding element in the mechanical domain with an analogous constitutive equation. All laws of circuit analysis, such as Kirchhoff's laws, that apply in the electrical domain also apply to the mechanical mobility analogy.

The mobility analogy is one of the two main mechanical-electrical analogies used for representing mechanical systems in the electrical domain, the other being the impedance analogy. The roles of voltage and current are reversed in these two methods, and the electrical representations produced are the dual circuits of each other. The mobility analogy preserves the topology of the mechanical system when transferred to the electrical domain whereas the impedance analogy does not. On the other hand, the impedance analogy preserves the analogy between electrical impedance and mechanical impedance whereas the mobility analogy does not.

Applications

The mobility analogy is widely used to model the behaviour of mechanical filters. These are filters that are intended for use in an electronic circuit, but work entirely by mechanical vibrational waves. Transducers are provided at the input and output of the filter to convert between the electrical and mechanical domains.[2]

Another very common use is in the field of audio equipment, such as loudspeakers. Loudspeakers consist of a transducer and mechanical moving parts. Acoustic waves themselves are waves of mechanical motion: of air molecules or some other fluid medium.[3]

Elements

Before an electrical analogy can be developed for a mechanical system, it must first be described as an abstract mechanical network. The mechanical system is broken down into a number of ideal elements each of which can then be paired with an electrical analogue.[4] The symbols used for these mechanical elements on network diagrams are shown in the following sections on each individual element.

The mechanical analogies of lumped electrical elements are also lumped elements, that is, it is assumed that the mechanical component possessing the element is small enough that the time taken by mechanical waves to propagate from one end of the component to the other can be neglected. Analogies can also be developed for distributed elements such as transmission lines but the greatest benefits are with lumped element circuits. Mechanical analogies are required for the three passive electrical elements, namely, resistance, inductance and capacitance. What these analogies are is determined by what mechanical property is chosen to represent voltage, and what property is chosen to represent current.[5] In the mobility analogy the analogue of voltage is velocity and the analogue of current is force.[6] Mechanical impedance is defined as the ratio of force to velocity, thus it is not analogous to electrical impedance. Rather, it is the analogue of electrical admittance, the inverse of impedance. Mechanical admittance is more commonly called mobility,[7] hence the name of the analogy.[8]

Resistance

The mechanical analogy of electrical resistance is the loss of energy of a moving system through such processes as friction. A mechanical component analogous to a resistor is a shock absorber and the property analogous to inverse resistance (conductance) is damping (inverse, because electrical impedance is the analogy of the inverse of mechanical impedance). A resistor is governed by the constitutive equation of Ohm's law,

The analogous equation in the mechanical domain is,

- where,

- G = 1/R is conductance

- R is resistance

- v is voltage

- i is current

- Rm is mechanical resistance, or damping

- F is force

- u is velocity induced by the force.[10]

Electrical conductance represents the real part of electrical admittance. Likewise, mechanical resistance is the real part of mechanical impedance.[11]

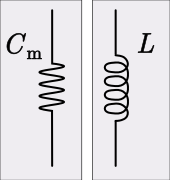

Inductance

The mechanical analogy of inductance in the mobility analogy is compliance. It is more common in mechanics to discuss stiffness, the inverse of compliance. A mechanical component analogous to an inductor is a spring. An inductor is governed by the constitutive equation,

The analogous equation in the mechanical domain is a form of Hooke's law,

- where,

- L is inductance

- t is time

- Cm = 1/S is mechanical compliance

- S is stiffness[13]

The impedance of an inductor is purely imaginary and is given by,

The analogous mechanical admittance is given by,

- where,

- Z is electrical impedance

- j is the imaginary unit

- ω is angular frequency

- Ym is mechanical impedance.[14]

Capacitance

The mechanical analogy of capacitance in the mobility analogy is mass. A mechanical component analogous to a capacitor is a large, rigid weight. A capacitor is governed by the constitutive equation,

The analogous equation in the mechanical domain is Newton's second law of motion,

- where,

- C is capacitance

- M is mass

The impedance of a capacitor is purely imaginary and is given by,

The analogous mechanical admittance is given by,

.[16]

.[16]

Inertance

A curious difficulty arises with mass as the analogy of an electrical element. It is connected with the fact that in mechanical systems the velocity of the mass (and more importantly, its acceleration) is always measured against some fixed reference frame, usually the earth. Considered as a two-terminal system element, the mass has one terminal at velocity ''u'', analogous to electric potential. The other terminal is at zero velocity and is analogous to electric ground potential. Thus, mass cannot be used as the analogue of an ungrounded capacitor.[17]

This led Malcolm C. Smith of the University of Cambridge in 2002 to define a new energy storing element for mechanical networks called inertance. A component that possesses inertance is called an inerter. The two terminals of an inerter, unlike a mass, are allowed to have two different, arbitrary velocities and accelerations. The costitutive equation of an inerter is given by,[18]

- where,

- F is an equal and opposite force applied to the two terminals

- B is the inertance

- u1 and u2 are the velocities at terminals 1 and 2 respectively

- Δu = u2 − u1

Inertance has the same units as mass (kilograms in the SI system) and the name indicates its relationship to inertia. Smith did not just define a network theoretic element, he also suggested a construction for a real mechanical component and made a small prototype. Smith's inerter consists of a plunger able to slide in or out of a cylinder. The plunger is connected to a rack and pinion gear which drives a flywheel inside the cylinder. There can be two counter-rotating flywheels in order to prevent a torque developing. Energy provided in pushing the plunger in will be returned when the plunger moves in the opposite direction, hence the device stores energy rather than dissipates it just like a block of mass. However, the actual mass of the inerter can be very small, an ideal inerter has no mass. Two points on the inerter, the plunger and the cylinder case, can be independently connected to other parts of the mechanical system with neither of them necessarily connected to ground.[19]

Smith's inerter has found an application in Formula One racing where it is known as the J-damper. It is used as an alternative to the now banned tuned mass damper and forms part of the vehicle suspension. It may have been first used secretly by McLaren in 2005 following a collaboration with Smith. Other teams are now believed to be using it. The inerter is much smaller than the tuned mass damper and smoothes out contact patch load variations on the tyres.[20] Smith also suggests using the inerter to reduce machine vibration.[21]

The difficulty with mass in mechanical analogies is not limited to the mobility analogy. A corresponding problem also occurs in the impedance analogy, but in that case it is ungrounded inductors, rather than capacitors, that cannot be represented with the standard elements.[22]

Resonator

A mechanical resonator consists of both a mass element and a compliance element. Mechanical resonators are analogous to electrical LC circuits consisting of inductance and capacitance. Real mechanical components unavoidably have both mass and compliance so it is a practical proposition to make resonators as a single component. In fact, it is more difficult to make a pure mass or pure compliance as a single component. A spring can be made with a certain compliance and mass minimised, or a mass can be made with compliance minimised, but neither can be eliminated altogether. Mechanical resonators are a key component of mechanical filters.[23]

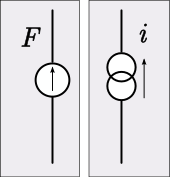

Generators

Analogues exist for the active electrical elements of the voltage source and the current source (generators). The mechanical analogue in the mobility analogy of the constant current generator is the constant force generator. The mechanical analogue of the constant voltage generator is the constant velocity generator.[26]

An example of a constant force generator is the constant-force spring. An example of a practical constant velocity generator is a lightly loaded powerful machine, such as a motor, driving a belt. This is analogous to a real voltage source, such as a battery, which remains near constant-voltage with load provided that the load resistance is much higher than the battery internal resistance.[27]

Transducers

Electromechanical systems require transducers to convert between the electrical and mechanical domains. They are analogous to two-port networks and like those can be described by a pair of simultaneous equations and four arbitrary parameters. There are numerous possible representations, but the form most applicable to the mobility analogy has the arbitrary parameters in units of admittance. In matrix form (with the electrical side taken as port 1) this representation is,

The element  is the short circuit mechanical admittance, that is, the admittance presented by the mechanical side of the transducer when zero voltage (short circuit) is applied to the electrical side. The element

is the short circuit mechanical admittance, that is, the admittance presented by the mechanical side of the transducer when zero voltage (short circuit) is applied to the electrical side. The element  , conversely, is the unloaded electrical admittance, that is, the admittance presented to the electrical side when the mechanical side is not driving a load (zero force). The remaining two elements,

, conversely, is the unloaded electrical admittance, that is, the admittance presented to the electrical side when the mechanical side is not driving a load (zero force). The remaining two elements,  and

and  , describe the transducer forward and reverse transfer functions respectively. They are both analogous to transfer admittances and are hybrid ratios of an electrical and mechanical quantity.[28]

, describe the transducer forward and reverse transfer functions respectively. They are both analogous to transfer admittances and are hybrid ratios of an electrical and mechanical quantity.[28]

Transformers

The mechanical analogy of a transformer is a simple machine such as a pulley or a lever. The force applied to the load can be greater or less than the input force depending on whether the mechanical advantage of the machine is greater or less than unity respectively. Mechanical advantage is analogous to the inverse of transformer turns ratio in the mobility analogy. A mechanical advantage less than unity is analogous to a step-up transformer and greater than unity is analogous to a step-down transformer.[29]

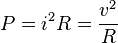

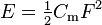

Power and energy equations

| Electrical quantity | Electrical expression | Mechanical analogy | Mechanical expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy supplied |  | Energy supplied |  |

| Power supplied |  | Power supplied |  |

| Power dissipation in a resistor |  | Power dissipation in a damper[9] |  |

| Energy stored in an inductor magnetic field |  | Potential energy stored in a spring[1] |  |

| Energy stored in a capacitor electric field |  | Kinetic energy of a moving mass[1] |  |

Examples

Simple resonant circuit

The figure shows a mechanical arrangement of a platform of mass M that is suspended above the substrate by a spring of stiffness S and a damper of resistance Rm. The mobility analogy equivalent circuit is shown to the right of this arrangement and consists of a parallel resonant circuit. This system has a resonant frequency, and may have a natural frequency of oscillation if not too heavily damped.[30]

Advantages and disadvantages

The principle advantage of the mobility analogy over its alternative, the impedance analogy, is that it preserves the topology of the mechanical system. Elements that are in series in the mechanical system are in series in the electrical equivalent circuit and elements in parallel in the mechanical system remain in parallel in the electrical equivalent.[31]

The principle disadvantage of the mobility analogy is that it does not maintain the analogy between electrical and mechanical impedance. Mechanical impedance is represented as an electrical admittance and a mechanical resistance is represented as an electrical conductance in the electrical equivalent circuit. Force is not analogous to voltage (generator voltages are often called electromotive force), but rather, it is analogous to current.[17]

History

Historically, the impedance analogy was in use long before the mobility analogy. Mechanical admittance and the associated mobility analogy were introduced by F. A. Firestone in 1932 to overcome the issue of preserving topologies.[32] W. Hähnle independently had the same idea in Germany. H. M. Trent developed a treatment for analogies in general from a mathematical graph theory perspective and introduced a new analogy of his own.[33]

References

- 1 2 3 Talbot-Smith, p. 1.86

- ↑ Carr, pp. 170–171

- ↑ Eargle, pp. 5–8

- ↑ Kleiner, pp. 69–70

- ↑ Busch-Vishniac, pp. 18–20

- 1 2 3 Eargle, p. 5

- ↑ Fahy & Gardonio, p. 71

- ↑ Busch-Vishniac, p. 19

- 1 2 Eargle, p. 4

- 1 2 Kleiner, p. 71

- ↑ Atkins & Escudier, p. 216

- ↑ Kleiner, p. 73

- ↑ Smith, p. 1651

- ↑ Kleiner, pp. 73–74

- ↑ Kleiner, p. 74

- ↑ Kleiner, pp. 72–73

- 1 2 Busch-Vishniac, p. 20

- ↑ Smith, pp. 1649–1650

- ↑ Smith, pp. 1650–1651

- ↑ De Groote

- ↑ Smith, p. 1661

- ↑ Smith, p. 1649

- ↑ Taylor & Huang, pp. 377–383

- ↑ Kleiner, p. 77

- Beranek & Mellow, p. 70

- ↑ Kleiner, p. 76

- Beranek & Mellow, p. 70

- ↑ Kleiner, pp. 76–77

- ↑ Kleiner, p. 77

- ↑ Debnath & Roy, pp. 566–567

- ↑ Kleiner, pp. 74–76

- Beranek & Mellow, pp. 76–77

- ↑ Eargle, pp. 4–5

- ↑ Busch-Vishniac, pp. 20–21

- Eargle, pp. 4–5

- ↑ Pierce, p. 321

- Firestone

- Pusey, p. 547

- ↑ Findeisen, p. 26

- Busch-Vishniac, pp. 19–20

- Hähnle

- Trent

Bibliography

- Atkins, Tony; Escudier, Marcel, A Dictionary of Mechanical Engineering, Oxford University Press, 2013 ISBN 0199587434.

- Beranek, Leo Leroy; Mellow, Tim J., Acoustics: Sound Fields and Transducers, Academic Press, 2012 ISBN 0123914213.

- Busch-Vishniac, Ilene J., Electromechanical Sensors and Actuators, Springer Science & Business Media, 1999 ISBN 038798495X.

- Carr, Joseph J., RF Components and Circuits, Newnes, 2002 ISBN 0-7506-4844-9.

- Debnath, M. C.; Roy, T., "Transfer scattering matrix of non-uniform surface acoustic wave transducers", International Journal of Mathematics and Mathematical Sciences, vol. 10, iss. 3, pp. 563–581, 1987.

- De Groote, Steven, "J-dampers in Formula One", F1 Technical, 27 September 2008.

- Eargle, John, Loudspeaker Handbook, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003 ISBN 1402075847.

- Fahy, Frank J.; Gardonio, Paolo, Sound and Structural Vibration: Radiation, Transmission and Response, Academic Press, 2007 ISBN 0080471102.

- Findeisen, Dietmar, System Dynamics and Mechanical Vibrations, Springer, 2000 ISBN 3540671447.

- Firestone, Floyd A., "A new analogy between mechanical and electrical systems", Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, vol. 4, pp. 249–267 (1932–1933).

- Hähnle, W., "Die Darstellung elektromechanischer Gebilde durch rein elektrische Schaltbilder", Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen aus dem Siemens-Konzern, vol. 1, iss. 11, pp. 1–23, 1932.

- Kleiner, Mendel, Electroacoustics, CRC Press, 2013 ISBN 1439836183.

- Pierce, Allan D., Acoustics: an Introduction to its Physical Principles and Applications, Acoustical Society of America 1989 ISBN 0883186128.

- Pusey, Henry C. (ed), 50 years of shock and vibration technology, Shock and Vibration Information Analysis Center, Booz-Allen & Hamilton, Inc., 1996 ISBN 0964694026.

- Smith, Malcom C., "Synthesis of mechanical networks: the inerter", IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, vol. 47, iss. 10, pp. 1648–1662, October 2002.

- Talbot-Smith, Michael, Audio Engineer's Reference Book, Taylor & Francis, 2013 ISBN 1136119736.

- Taylor, John; Huang, Qiuting, CRC Handbook of Electrical Filters, CRC Press, 1997 ISBN 0849389518.

- Trent, Horace M., "Isomorphisms between oriented linear graphs and lumped physical systems", The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, vol. 27, pp. 500–527, 1955.