Misty Copeland

| Misty Copeland | |

|---|---|

Copeland in Coppélia in 2014 | |

| Born |

Misty Danielle Copeland September 10, 1982 Kansas City, Missouri, United States |

| Residence | Manhattan, New York City, United States |

| Education | San Pedro High School |

| Occupation | Ballet dancer |

| Years active | 1995–present |

| Home town | San Pedro, California, United States |

| Website |

www |

| Current group | American Ballet Theatre |

Misty Danielle Copeland (born September 10, 1982)[1] is an American ballet dancer for American Ballet Theatre (ABT), one of the three leading classical ballet companies in the United States.[2] On June 30, 2015, Copeland became the first African American woman to be promoted to principal dancer in ABT's 75-year history.[3]

Copeland was considered a prodigy who rose to stardom despite not starting ballet until the age of 13. By age 15, her mother and ballet teachers, who were serving as her custodial guardians, fought a custody battle over her. Meanwhile, Copeland, who was already an award-winning dancer, was fielding professional offers.[4] The 1998 legal issues involved filings for emancipation by Copeland and restraining orders by her mother.[5] Both sides dropped legal proceedings, and Copeland moved home to begin studying under a new teacher who was a former ABT member.[6]

In 1997, Copeland won the Los Angeles Music Center Spotlight Award as the best dancer in Southern California. After two summer workshops with ABT, she became a member of ABT's Studio Company in 2000 and its corps de ballet in 2001, and became an ABT soloist in 2007.[7] As a soloist from 2007 to mid-2015, she was described as having matured into a more contemporary and sophisticated dancer.[8]

In addition to her dance career, Copeland has become a public speaker, celebrity spokesperson and stage performer. She has written two autobiographical books and narrated a documentary about her career challenges, A Ballerina's Tale. In 2015, she was named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time, appearing on its cover. She performed on Broadway in On the Town, toured as a featured dancer for Prince and appeared on the reality television shows A Day in the Life and So You Think You Can Dance. She has endorsed products and companies such as T-Mobile, Dr Pepper, Seiko and Under Armour.

Early life

Copeland was born in Kansas City, Missouri, and raised in the San Pedro community of Los Angeles, California.[7] Copeland's father, Doug Copeland, is German American and African American,[9] while her mother, Sylvia DelaCerna, is Italian American and African American and was adopted by African American parents.[10][11] Misty Copeland is the youngest of four children from her mother's second marriage; the others are Erica Stephanie Copeland, Douglas Copeland Jr. and Christopher Ryan Copeland. She also has two younger half-siblings, Lindsey Monique Brown and Cameron Koa DelaCerna, one each from her mother's third and fourth marriages.[11] Copeland did not see her father between the ages of two and twenty-two.[12] Her mother, a former Kansas City Chiefs cheerleader, had studied dance.[11] She is a trained medical assistant, but worked mostly in sales.[13]

Between the ages of three and seven, Copeland lived in Bellflower, California, with her mother and her mother's third husband, Harold Brown, a Santa Fe Railroad sales executive.[14] The family moved to San Pedro, where Sylvia eventually married her fourth husband, radiologist Robert DelaCerna, and where Misty attended Point Fermin Elementary School.[15] When she was seven, Copeland saw the film Nadia on television, and suddenly Nadia Comăneci was her new role model.[16] At age eleven, she found her first creative outlet at a Boys & Girls Club wood shop class.[17] Copeland never studied ballet or gymnastics formally until her teenage years, but she enjoyed choreographing flips and dance moves to Mariah Carey songs in her youth.[18] Following in the footsteps of her older sister Erica, who had starred on the Dana Middle School drill team that won statewide competitions, Copeland became captain of the Dana drill team.[19] Her natural presence and skill came to the attention of her classically trained Dana drill team coach, Elizabeth Cantine, in San Pedro.[5][11]

In 1995, Copeland was introduced to ballet in classes at her local Boys & Girls Club by Cynthia Bradley, who was a friend of Cantine's.[20][21][22] DelaCerna allowed Copeland to go to the club after school until the workday ended and Bradley, a former dancer, taught a free ballet class there once a week.[11] Bradley invited Copeland to attend class at the small local ballet school, San Pedro Dance Center. She initially declined the offer, however, because her mother did not have a car, was working 12–14 hours a day, and her oldest sister Erica was working two jobs.[11][21] Copeland began her ballet studies at the age of 13 at the San Pedro Dance Center when Cynthia Bradley began picking her up from school.[7][21]

During her first year of middle school, her mother separated from Robert.[23] After living with various boyfriends, DelaCerna moved with all of her children into two small rooms at the Sunset Inn in Gardena, California.[21][24] She told Copeland that she would have to give up ballet, but Bradley wanted Copeland to continue and offered to host her. DelaCerna agreed to this, and Copeland moved in with Bradley and her family.[25] Eventually, Copeland and DelaCerna signed a management contract as well as a life-story contract with Bradley. Copeland spent the weekdays with the Bradleys near the coast and the weekends at home with her mother,[5] a two-hour bus ride away.[26] By the age of fourteen, Copeland was the winner of a national ballet contest and won her first solo role.[26] The Bradleys introduced Copeland to books and videos about ballet. When she saw Paloma Herrera, a principal ballerina with ABT, perform at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Copeland began to idolize her as much as she did Mariah Carey.[11] After three months of study, Copeland was en pointe.[21] The media first noticed her when she drew 2,000 patrons per show as she performed as Clara in the The Nutcracker after only eight months of study.[11] A larger role in Don Quixote and a featured role in The Chocolate Nutcracker, an African American version of the tale, narrated by Debbie Allen, soon followed.[11]

The summer before her fifteenth birthday, Bradley began to homeschool Copeland to free up time for dance.[27] At fifteen years old, Copeland won first place in the Los Angeles Music Center Spotlight Awards[6] at the Chandler Pavilion in March 1998.[28] Copeland said it was the first time she ever battled nervousness.[6] The winners received scholarships between $500 and $2500.[29] Copeland's victory in the 10th annual contest among gifted high school students in Southern California[28] secured her recognition by the Los Angeles Times as the best young dancer in the Greater Los Angeles Area.[30]

Copeland studied at the San Francisco Ballet School in 1998 after winning the Spotlight award.[7][21] She and Bradley selected the workshop with the San Francisco Ballet over offers from the Joffrey Ballet, ABT, Dance Theater of Harlem and Pacific Northwest Ballet.[11][31] Of the programs she auditioned for, only the New York City Ballet declined to make her an offer.[31] San Francisco Ballet, ABT and New York City Ballet are regarded as the three preeminent classical ballet companies in the US.[2] During the six week workshop at San Francisco, Copeland was placed in the most advanced classes[32] and was under a full tuition plus expenses scholarship.[33] At the end of the workshop, she received one of the few offers to continue as a full-time student at the school, but with encouragement from her mother to return home and from Bradley to return to the personal attention the Bradley family offered, she declined with dreams of a subsequent summer with ABT.[34] She returned home to controversy, as her mother resented the Bradleys' influence.[35]

Custody battle

After Copeland returned from her summer 1998 San Francisco Ballet experience, her mother informed her that she would be moving back in with her and not resuming her study with the Bradleys.[11][21] Copeland was distraught with fear that she would not be able to dance.[5] She had heard the term emancipation while in San Francisco;[21] the procedure was common among young performers.[11] The Bradleys introduced Copeland to Steven Bartell, a lawyer who explained the emancipation petition process.[11][21] Copeland says she understood the process as a way to make everything better.[21] The Bradleys encouraged her to be absent when the emancipation petition was delivered to her mother.[21] Copeland ran away from home for three days and stayed with a friend, while Bartell filed the emancipation papers.[5][21] After her mother reported Copeland missing, she was told about the emancipation petition.[21] Three days after running away, Copeland was taken to the police station by Bartell.[5][21] DelaCerna engaged lawyer Gloria Allred and applied for a series of restraining orders, which included the Bradleys' five-year-old son, who had been Copeland's roommate, and Bartell. The order was partly intended to preclude contact between the Bradleys and Copeland, but it did not have proper legal basis, since there had been no stalking and no harassment.[21]

The custody controversy was highly publicized in the press (especially Los Angeles Times and Extra),[21] starting in August and September 1998.[4][21] Parts of the press coverage spilled over into op-ed articles.[36] The case was heard in Torrance, in the Superior Court of Los Angeles County. DelaCerna claimed that the Bradleys had brainwashed Copeland into filing suit for emancipation from her mother,[4][37][38] Allred claimed that the Bradleys had turned Copeland against her mother by belittling DelaCerna's intelligence.[37] The Bradleys noted that the management contract gave them authority, but they stated that they would not seek to enforce their rights to twenty percent of Copeland's earnings until she became eighteen.[4][5]

The dismissal of the emancipation petition accomplished Sylvia's main goal of keeping the family bonds intact and strong, without interference by third parties. ... Another concern of Sylvia in filing a request for restraining orders was that she did not believe it was in Misty's best interest to have continuing contact with the Bradleys. In the sworn declarations filed by the Bradleys in response to the restraining order they said that 'we have not and will never do anything to interfere with Misty's relationship with her mother.' ... Since Sylvia has accomplished all of the goals that she intended to achieve when she filed her papers with the court we have chosen not to proceed to seek an injunction in this matter.

After DelaCerna stated that she would always make sure Copeland could dance, both the emancipation papers and restraining orders were dropped.[5] Copeland, who claimed she did not even understand the term emancipation, withdrew the petition after informing the judge that such charges no longer represented her wishes.[26][30] Still, DelaCerna wanted the Bradleys out of her daughter's life.[30] Copeland re-enrolled at San Pedro High School for her junior year (1998–99), on pace to be a part of her original class of 2000.[7][36] DelaCerna sought Cantine's advice on finding a new ballet school.[39] Copeland began ballet study at Lauridsen Ballet Centre with former ABT dancer Diane Lauridsen, although her dancing was now restricted to afternoons in deference to her schooling.[11][21] Late in 1998, all parties appeared on Leeza Gibbons' talk show, Leeza, where Copland sat silently as the adults "bickered shamelessly".[21] As a student, Copeland had a 3.8/4.0 GPA through her junior year of high school.[36] In 2000, DelaCerna stated that Copeland's earnings from ballet were set aside in a savings account and only used as needed.[36]

American Ballet Theatre

Early ABT career

Copeland auditioned for several dance programs in 1999, and each made her an offer to enroll in its summer program.[11] She performed with ABT as part of its 1999 and 2000 Summer Intensive programs.[40][41] During the summer of 1999, the topic of whether Copeland would stay if invited came up, and she responded affirmatively, although her mother insisted finishing high school was important.[11] During that summer, she was told that she would likely be invited to stay after she graduated in 2000, and by the end of the summer she was asked to skip her senior year and join the studio company.[11] Copeland returned to California for her senior year, even though ABT arranged to pay for her performances, housing accommodations and academic arrangements.[11] She studied at the Summer Intensive Program on full scholarship for both summers and was declared ABT's National Coca-Cola Scholar in 2000.[7] In the 2000 Summer Intensive Program, she danced the role of Kitri in Don Quixote.[7][41] Of the 150 dancers in the 2000 Summer Intensive Program, she was one of six selected to join the junior dance troupe.[41]

In September 2000, she joined the ABT Studio Company, which is ABT's second company, and became a member of its Corps de ballet in 2001.[7][42] As part of the Studio Company, she performed a duet in Tchaikovsky's The Sleeping Beauty.[43] Eight months after joining the company, she was sidelined for nearly a year by a lumbar stress fracture.[44] When Copeland joined the company, she weighed 108 pounds (she is 5 feet 2 inches (1.57 m) tall).[45] At age 19, her puberty had been delayed, a situation common in ballet dancers.[45][46] After the lumbar fracture, her doctor told her that inducing puberty would help to strengthen her bones, and he prescribed birth control pills. Copeland recalls that in one month she gained 10 pounds, and her small breasts swelled to double D-cup size: "Leotards had to be altered for me ... to cover my cleavage, for instance. I hated this sign that I was different from the others. ... I became so self-conscious that, for the first time in my life, I couldn’t dance strong. I was too busy trying to hide my breasts."[45] Management noticed and called her in to talk about her body. The professional pressure to conform to conventional ballet aesthetics resulted in body image struggles and a binge eating disorder.[45][47] Copeland says that, over the next year, new friendships outside of ABT, including with Victoria Rowell and her boyfriend, Olu Evans, helped her to regain confidence in her body. She explained, "My curves became an integral part of who I am as a dancer, not something I needed to lose to become one. I started dancing with confidence and joy, and soon the staff at ABT began giving me positive feedback again. And I think I changed everyone’s mind about what a perfect dancer is supposed to look like."[45][48] During her years in the corps, as the only Black woman in a the company, Copeland also felt the burden of her ethnicity in many ways and contemplated a variety of career choices.[49] Recognizing that Copeland's isolation and self-doubt were standing in the way of her talent, ABT's artistic director, Kevin McKenzie, asked writer and arts figure Susan Fales-Hill to mentor Copeland. Fales-Hill introduced Copeland to Black women trailblazers who encouraged Copeland and helped her to gain perspective.[50]

Early career reviews mentioned Copeland as more radiant than higher ranking dancers, and she was named to the 2003 class of Dance Magazine's "25 to Watch".[51] In 2003, she was favorably reviewed for her roles as a member of the corps in La Bayadère and William Forsythe's workwithinwork.[52][53] Recognition continued in 2004 for roles in ballets such as Raymonda, workwithinwork,[54][55][56] Amazed in Burning Dreams,[57] Sechs Tänze, Pillar of Fire,[58] "Pretty Good Year", "VIII" and "Sinfonietta, where she "stood out in the pas de trois – whether she was gliding across the floor or in a full lift, she created the illusion of smoothness".[59] She also danced the Hungarian Princess in Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake.[60] The 2004 season is regarded as her breakthrough season.[54] She was included in the 2004 picture book by former ABT dancer Rosalie O'Connor titled Getting Closer: A Dancer's Perspective.[61] Also in 2004, she met her biological father for the first time.[62]

In 2005, her most notable performance was in George Balanchine's Tarantella.[63] she also danced the Lead Polovtsian Girl in "Polovtsian Dances" from Prince Igor.[64] In 2006, she was acknowledged for her meticulous classical performance style in Giselle[65] and created a role in Jorma Elo's Glow–Stop.[66] That year, she also returned to Southern California to perform at Orange County Performing Arts Center[67] and danced one of the cygnets and reprised her role as the Hungarian Princess in Swan Lake in New York.[68] In both 2006 and 2007, Copeland danced the role of Blossom in James Kudelka's Cinderella.[69] Copeland's "old-style" performance continued to earn her praise in 2007.[8] In 2007, she danced the Fairy of Valor in The Sleeping Beauty.[70] Other roles that Copeland played before she was appointed a soloist by ABT included Twyla Tharp roles in In the Upper Room and Sinatra Suite as well as a role in Mark Morris's Gong.[71]

Soloist

Copeland was appointed a soloist at ABT in August 2007,[21] one of the youngest ABT dancers promoted to soloist.[72] Although, she was described by early accounts as the first African American woman promoted to soloist for ABT,[6][20] Anne Benna Sims and Nora Kimball were soloists with ABT in the 1980s.[73][74][75][76] Male soloist Keith Lee also preceded her.[77] As of 2008, Copeland was the only African-American woman in the dance company during her entire ABT career, and the only male African American in the company, Danny Tidwell, left in 2005.[6][78] In an international ballet community with a lack of diversity,[79][80] she was so unusual as an African American ballerina, that she endured cultural isolation.[81] She has been described in the press as the Jackie Robinson of classical ballet.[6] Copeland feels that since the female dancer is the focus of ballet, her history as a trail-blazing performer and role model has extra significance.[6]

Copeland was a standout among her peers.[82] In her first season as a soloist at New York City Center, in which avant-garde ballets works were performed, she presented a Balanchine Ballo della Regina role,[83] earning praise.[84] Also in 2007, she created a leading role in C. to C. (Close to Chuck), choreographed by Jorma Elo to A Musical Portrait of Chuck Close, Études 2, 9 & 10, by Philip Glass.[85][86] Her performances of Tharp works in the same season were recognized,[87][88] and she was described as more sophisticated and contemporary as a soloist than she had been as a corps dancer.[89] Her summer 2008 Metropolitan Opera House (the Met) season performances in Don Quixote and Sleeping Beauty were also well received.[90][91]

During the 2008–09 season, Copeland received publicity for roles in Twyla Tharp's Baker's Dozen and Paul Taylor's Company B.[92][93] During the 2009 Spring ABT season at the Met, Copeland performed Gulnare in Le Corsaire and leading roles in Taylor's Airs and Balanchine's Tschaikovsky Pas de Deux from Swan Lake. Her Annenberg Fellowship that year included training for the Pas de Deux.[94][95] Late that year, she performed in ABT's first trip to Beijing at the new National Center for the Performing Arts.[96] In 2009, Copeland created a role in Aszure Baron's One of Three.[97]

In 2010, Copeland performed in Birthday Offering at the Met[98] and at the Guggenheim Museum danced to David Lang's music.[99][100] She also created the Spanish Dance in ABT artist-in-residence Alexei Ratmansky's new version of The Nutcracker, premiered at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.[101] In early 2011, she was well-received at the Kennedy Center as the Milkmaid in Ratmansky's The Bright Stream, a remake of a banned comic ballet.[102] In of Black History Month in 2011, Copeland was selected by Essence as one of its 37 Boundary-breaking black women in entertainment.[103] That same month, she toured with Company B, performed at Sadler's Wells Theatre in London.[104] In May, she created a role in Ratmansky's Dumbarton, danced to Stravinsky's chamber concerto, Dumbarton Oaks. Alastair Macaulay of The New York Times found the piece too intimate for the cavernous Met, but he noted: "Misty Copeland gives sudden hints of need and emotional bleakness in a duet ... too much is going on to explain itself at one viewing; but at once I know I’m emotionally and structurally gripped."[105] Her Summer 2011 ABT solos included the peasant pas de deux in Giselle[106] and, in Ratmansky's The Bright Stream at the Met in June, her reprise of the Milkmaid was called "luminous, teasingly sensual".[107][108] She reprised the role again in July at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles with a performance described as "sly".[109] As a flower girl, she was described as glittering in Don Quixote.[110] In August, she performed at the Vail International Dance Festival in the Gerald Ford Amphitheater in Vail, Colorado.[111] In November, she danced in Taylor's Black Tuesday.[112]

In 2012, Copeland began achieving solo roles in full-length standard repertory ballets rather than works that were mostly relatively modern pieces.[113] She starred in The Firebird, with choreography by Ratmansky at the Segerstrom Center for the Arts in Costa Mesa, California. It premiered on March 29, 2012. The performance was hailed by Laura Bleiberg in the Los Angeles Times as one of the year's best dance performances.[114] That year, Copeland was recognized by The Council of Urban Professionals as their Breakthrough Leadership Award winner.[115] She also danced the role of Gamzatti in La Bayadère at the Met to praise from Alastair Macaulay of The New York Times, who noted her "adult complexity and worldly allure".[116] The Firebird was again performed at the Met in June 2012, with Copeland to alternate in the lead.[117][118][119] It was Copeland's first leading role at ABT.[118] Backstage described it as her "most prestigious part" to date.[120][121] After only one New York performance in the role, Copeland withdrew from the entire ABT season due to six stress fractures in her tibia. She was sidelined for seven months after her October surgery.[122] Upon her return to the stage, she danced the Queen of the Dryads in Don Quixote in May 2013.[113] Nelson George began filming a documentary leverage the chance to present her comeback.[123]

Copeland reprised her role as Gulnare in June 2013 in the pirate-themed Le Corsaire.[124][125] She also played an Odalisque in the same ballet.[126] Later in the year, she danced in Tharp's choreography of Bach Partita for Violin No. 2 in D minor for solo violin,[127][128] and as Columbine in ABT's revival of Ratmansky's Nutcracker at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.[129][130]

In May 2014, Copeland performed the lead role of Swanilda in Coppélia at the Met.[131][132] According to Los Angeles Times writer Jevon Phillips, she is the first African American woman to dance the role.[133] The same month, she was praised in the dual role of Queen of the Dryads and Mercedes in Don Quixote by Brian Seibert of The New York Times, although Jerry Hochman of Critical Dance felt that she was not as impressive in the former role as in the latter.[134][135] Later in May, the Met staged a program of one-act ballets consisting of Theme and Variations, Duo Concertant and Gaîté Parisienne,[136] featuring Copeland in all three.[133] Siebert praised her work as the lead in Balanchine's choreography of Igor Stravinsky's Duo Concertant for violin and piano performed by Benjamin Bowman and Emily Wong.[137] Of her Flower Girl in Gaîté Parisienne, Apollinaire Scherr of The Financial Times wrote that she "tips like a brimming watering can into the bouquets her wooers hold out to her".[138] Copeland was a "flawless" demi-soloist in Theme and Variations, according to Colleen Boresta of Critical Dance.[136]

In June 2014 at the Met, she danced the Fairy Autumn in the Frederick Ashton Cinderella, cited for her energetic exuberance in the role by Hochman, who missed the "varied texture and nuance that made it significantly more interesting" in the hands of ABT's Christine Shevchenko.[139] That month, she played Lescaut's Mistress in Manon in which role Marjorie Liebert of BroadwayWorld.com described her as "seductive and ingratiating".[140][141] Also in June, she performed the role of Gamzatti in La Bayadère.[142] Copeland performed the Odette/Odile double role in Swan Lake in September when the company toured in Brisbane, Australia.[143][144] Her ascension to more prominent roles occurred as three ABT principal dancers (Paloma Herrera, Julie Kent and Xiomara Reyes) entered their final seasons before retirement.[145] In early October, Copeland performed several pieces including a principal role in Tharp's Bach Partita at Chicago's Auditorium Theatre.[146] In October, Copeland made her New York debut in one of the six principal roles in Tharp's Bach Partita[147] and created a role in Liam Scarlett's With a Chance of Rain.[148] That December, when ABT revived Ratmansky's Nutcracker at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Copeland played the role of Clara, the Princess.[149] The same month, at the Kennedy Center Honors, she was described as "sublime" in Tchaikovsky's Pas de Deux by the New York City CBS News affiliate.[150]

In March 2015, Copeland danced the role of Princess Florine in The Sleeping Beauty at the Segerstrom Center for the Arts in Costa Mesa, California.[151] She made her American debut as Odette/Odile in Swan Lake with The Washington Ballet, opposite Brooklyn Mack as Prince Siegfried, in April at the Eisenhower Theater in the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.[152] The performance was the company's first presentation of Swan Lake in its 70-year history.[153] In May 2015, she played Cowgirl in Rodeo,[154] Bianca in Othello[155] and Zulma in Giselle.[156] She was selected for the 2015 Time 100. As a result, Copeland appeared on the cover of Time, making her the first dancer on the cover since Bill T. Jones in 1994.[157][158] In June, Copeland created the small role of the Fairy Fleur de farine (Wheat flower) in Ratmansky's The Sleeping Beauty.[159] The same month, she made her debut in Romeo and Juliet on short notice a few days before her scheduled debut performance on June 20.[160] Later in June, Copeland made her New York debut in the Odette/Odile double role from Swan Lake that is described by Macauley as "the most epic role in world ballet". Her performance at the Met was regarded as a success.[161][162] Her performance in the role had been anticipated as a "a crowning achievement" in wide-ranging media outlets and by a broad spectrum of fans and supporters.[163][164] Wilkinson and Anderson were on hand to present her bouquets on stage.[161] Some viewed this performance as a sign that her promotion to principal was forthcoming.[165]

Principal dancer

On June 30, 2015, Copeland became the first African-American woman to be promoted to principal ballerina in ABT's 75-year history.[3][166] Copeland's achievement was groundbreaking, as there have been very few principal ballerinas at major companies.[167] Lauren Anderson became a principal at Houston Ballet in 1990, the first principal ballerina at any major American company.[168] According to the 2015 documentary about Copeland, A Ballerina's Tale, "there has never been a Black female principal dancer at a major international company".[169]

Copeland next accepted the role of Ivy Smith in the Broadway revival of On The Town, which she played for two weeks from August 25 to September 6.[170][171] Her debut on Broadway was favorably reviewed in The New York Times,[172] The Washington Post,[173] and other media.[174][175]

In October in New York, Copeland performed in the revival of Tharp's choreography of the Brahms-Haydn Variations,[176] in Frederick Ashton's Monotones I,[177] and "brought a seductive mix of demureness and sex appeal to 'Rum and Coca-Cola'" in Paul Taylor's Company B.[178] The same month, she created the role of His Loss in AfterEffect by Marcelo Gomes, danced to Tchaikovsky's Souvenir de Florence, at Lincoln Center.[179] When ABT brought Ratmansky's Nutcracker to Segerstrom Center for the Arts in December 2015, Copeland reprised the role of Clara.[180]

In January 2016, Copeland reprised the role of Princess Florine in The Sleeping Beauty at the Kennedy Center, choreographed by Ratmansky.[181]

Public persona

In March 2009, Copeland spent two days in Los Angeles filming a music video with Prince for a cover of "Crimson and Clover", the first single from his 2009 studio album Lotusflower.[94][182] Prince asked her to dance along to the song in unchoreographed ballet movements. She described his instructions as "Be you, feel the music, just move", and upon request for further instruction, "Keep doing what you're doing".[106] She also began taking acting lessons in 2009.[94] During the New York City and New Jersey portions of Prince's Welcome 2 America tour, Copeland performed a pas de deux en pointe to his song "The Beautiful Ones", the opening number at the Izod Center and Madison Square Garden.[183] Prince had previously invited her onstage at a concert in Nice, France.[184] In April 2011, she performed alongside Prince on the Lopez Tonight show, dancing to "The Beautiful Ones."[185]

In September 2011, she was featured in the Season 1, episode 5 of the Hulu web series A Day in the Life.[186][187] Copeland was interviewed in the November 2013 Vogue Italia.[188] She was a guest judge for the 11th season of FOX's So You Think You Can Dance.[189] New Line Cinema has optioned her memoir, Life in Motion, for a screen adaptation[190] and the Oxygen network has expressed interest in producing a reality docuseries about Copeland mentoring a Master Class of aspiring young dancers.[191][192]

A Ballerina's Tale, a documentary film about Copeland, debuted at the Tribeca Film Festival in April 2015.[193] The film was released through video on demand in October 2015 the day before its limited release in theaters.[194] It was first aired on February 8, 2016 as part of PBS' Independent Lens series.[195][196] In May, she was featured on 60 Minutes in a segment with correspondent Bill Whitaker.[197][198] In June, she served as a presenter at the 69th Tony Awards.[199] She was included in the 2015 International Best Dressed List, published by Vanity Fair.[200] in October 2015, she performed on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert with musical accompaniment by Yo-Yo Ma, who played Courante from Bach's Cello Suite No. 2.[201]

Honors

In 2008, Copeland won the Leonore Annenberg Fellowship in the Arts, which funds study with master teachers and trainers outside of ABT.[202] The two-year fellowships are in recognition of "young artists of extraordinary talent with the goal of providing them with additional resources in order to fully realise their potential".[203] In 2013, she was named National Youth of the Year Ambassador by the Boys & Girls Clubs of America.[204] In 2014, Copeland was named to the President's Council on Fitness, Sports, and Nutrition[205] and received an honorary doctorate from the University of Hartford for her contributions to classical ballet and helping to diversify the art form.[206][207] Copeland was a Dance Magazine Awards 2014 honoree.[208] After her promotion as principal dancer, Copeland was named one of Glamour's Women of the Year for 2015;[209][210] one of ESPN's 2015 Impact 25 athletes and influencers who have made the greatest impact for women in sports;[211] and, by Barbara Walters, one of the 10 "most fascinating" people of 2015.[212]

Ventures

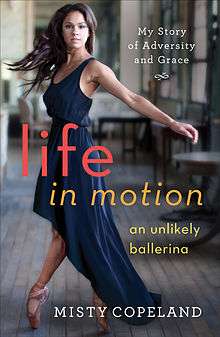

In December 2011, she unveiled a line of dancewear, called M by Misty, that she designed.[213] She has also produced celebrity calendars.[214] In March 2014, Copeland released a memoir, Life in Motion: An Unlikely Ballerina, co-authored by Charisse Jones.[215] Her children's picture book, titled Firebird, with illustrator Christopher Myers, was released in September 2014.[216] In November 2015, she announced a third book, Ballerina Body, planned to be a health and fitness guide.[217]

Endorsements

Copeland was featured in T-Mobile's ads for the BlackBerry in 2010[218] and an ad for Dr. Pepper in 2013.[219] In September 2013, she became a spokesperson for Project Plié, a national initiative with the goal of broadening the pipeline of leadership within ballet.[220] Copeland became a brand ambassador for Seiko in March 2015.[221]

In early 2014, she became a sponsored athlete for Under Armour,[222] which paid her more than her ballet career.[223] The Under Armour women-focused ad campaign starring Copeland was widely publicized,[224][225][226] eventually resulting in her being named ABC World News Person of the week on August 8, 2014.[227] The ad campaign was recognized by Adweek as one of The 10 Best Ads of 2014, where it was recognized as "The year's best campaign targeting women".[228] By July 2015, Copeland (along with Steph Curry and Jordan Spieth) was credited with leading to a surge in demand for Under Armor products.[229]

Personal life

Copeland lives with her fiancé, attorney Olu Evans, on Manhattan's Upper West Side.[113][230] The couple were introduced to each other around 2004 by Evans' cousin, Taye Diggs.[231] In a cover story in the September 2015 issue of Essence, Copeland announced her engagement to Evans.[232]

Published works

- Copeland, Misty (with Charisse Jones) (2014). Life in Motion: An Unlikely Ballerina. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4767-3798-0.

- Copeland, Misty (2014). Firebird. G.P. Putnam's Sons Books for Young Readers. ISBN 978-0-399-16615-0.

References

- ↑ "Minkus – "Don Quixote" – Ballet ~ Misty Copeland – 15 – 1997 – VOB". YouTube. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- 1 2 Jennings, Luke (2007-02-18). "One step closer to perfection: The best of Balanchine lights up London – but Stravinsky in Birmingham must not be missed". The Observer. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- 1 2 Cooper, Michael (30 June 2015). "Misty Copeland Is Promoted to Principal Dancer at American Ballet Theater". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 June 2015.; and Feeley, Sheila Anne (July 1, 2015). "Historic 1st for ballet company". A.M. New York. p. 3. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Custody Hearing for Ballerina Rescheduled". Los Angeles Times. 1998-08-28. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hastings, Deborah (1998-11-01). "Teen dancer stumbles in adults' tug-of-war". SouthCoast Today. AP. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Farber, Jim (2008-03-27). "This Swan is More than Coping". LA.com. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Misty Copeland". Ballet Theatre Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- 1 2 Dunning, Jennifer (2007-05-19). "For Ballet's Shifting Casts, a Big Question: Who Will Lift It to the Realm of Poetry?". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Turits, Meredith. "Misty Copeland, American Ballet Theatre's First African-American Soloist in 20 Years, Talks Breaking Barriers with Aplomb", Glamour magazine, April 23, 2012, accessed December 30, 2015

- ↑ Copeland, pp. 13–14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Adato, Allison (1999-12-05). "Solo in the City". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ↑ Copeland, p. 9.

- ↑ Copeland, p. 55.

- ↑ Copeland, pp. 10–14.

- ↑ Copeland, pp. 14–16.

- ↑ Copeland, p. 21.

- ↑ "Misty Copeland". Boys & Girls Clubs of America. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- ↑ Winter, Jessica (2010-06-17). "5 Things Misty Copeland Knows for Sure". O: The Oprah Magazine. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- ↑ Copeland, pp. 27–29.

- 1 2 McCrary, Crystal (Fall 2008). "A Tale of Two Swans". Uptown (Chicago) (Miller Publishing Group) (17): 100–103.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Sims, Caitlin (December 1998). "Battle Over Misty Copeland Draws Media – young ballet student center of controversy as to whether her parents or another family should direct her life". Dance Magazine (CNET Networks, Inc.). Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ↑ Copeland, p. 32.

- ↑ Copeland, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Copeland, pp. 58–60.

- ↑ Copeland, pp. 63–65.

- 1 2 3 Jerome, Richard, Christina Cheakalos and Susan Horsburgh (2003-02-17). "Prodigies Grow Up". People. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ↑ Copeland, p. 81.

- 1 2 Haithman, Diane (1998-03-21). "Giving Young Performers a Chance to Earn the Spotlight". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- ↑ Cardenas, Jose (1998-03-23). "Spotlight to Fall on Teenage Performers; Arts: Dorothy Chandler Pavilion will host the annual awards, which will feature 12 finalists competing for $2,500 and $500 scholarships". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- 1 2 3 Glionna, John M. (1998-09-01). "Ballet Prodigy's Life Undergoes More Twists; Courts: Mother drops request for restraining order against teachers. Girl withdraws emancipation plea". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- 1 2 Copeland, pp. 97–99.

- ↑ Copeland, p. 103.

- ↑ Copeland, p.104.

- ↑ Copeland, pp. 111–14.

- ↑ Copeland, pp. 118–19.

- 1 2 3 4 "Misty Copeland: Should She Stay or Should She Go?". Los Angeles Times. 2000-01-16. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- 1 2 Glionna, John M. (1998-08-23). "Trapped in a Dispiriting Dance of Wills; Ballet: Prodigy's mother and former teacher are locked in legal duel over her". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- ↑ "News in Brief: A summary of developments across Los Angeles County; Community News File / Torrance; Custody Hearing for Ballerina Rescheduled". Los Angeles Times. 1998-08-28. Retrieved 2011-01-17.

- ↑ Copeland, pp. 119.

- ↑ Dunning, Jennifer (1999-08-02). "Dance Review; A Study In Ballet Both Clean And Lively". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- 1 2 3 Dunning, Jennifer (2000-08-08). "Dance Review; Ballet Theater Shows Off a Nation's Students". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ "Spotlight Awards: The Spotlight Awards benefit from a variety of wonderful judges and presenters who mentor the young students through the Spotlight Awards process". The Music Center / Performing Arts Center. 2008. Archived from the original on July 22, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Anderson, Jack (2000-12-19). "Dance Review; A Classic Pas de Deux in the Hands of Talented Novices". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Copeland, pp. 159–61.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bried, Erin. "Stretching Beauty: Ballerina Misty Copeland on Her Body Struggles", Self magazine, March 18, 2014, accessed January 31, 2016

- ↑ Hayes, Hannah Maria. "When Bodies Change", Dance Teacher magazine, May 23, 2011, accessed January 31, 2016

- ↑ Copeland, pp. 164–69.

- ↑ Glasser, Hana. "If Misty Copeland’s Body Is 'Wrong', I Don't Want to Be Right", Slate, August 5, 2014, accessed January 31, 2016

- ↑ Copeland, pp. 172–87.

- ↑ McNamara, Mary. "A Ballerina's Tale follows Misty Copeland's incredible rise in the ballet world", Los Angeles Times, February 8, 2016

- ↑ Ossola, Cheryl (January 2003). "25 to watch – dancers". Dance Magazine. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ↑ Kisselgoff, Anna (2003-05-13). "Ballet Theater Review; Jealousy and Betrayal In an Oriental Temple". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Kisselgoff, Anna (2003-10-28). "Ballet Theater Review; Choreographer Unfurls His Devotion To Process". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- 1 2 Kisselgoff, Anna (2004-11-04). "Dance Review – American Ballet Theater: Out of an Ensemble Emerge Two Individual Spirits". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Kisselgoff, Anna (2004-05-12). "Ballet Theater Review; Meaty Excerpts And Novelties Open a Season". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Dunning, Jennifer (2004-06-05). "Ballet Review; Giving a Classic a Jolt of Youthful Vigor". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Zlokower, Roberta E. "American Ballet Theatre: Les Sylphides, Mozartiana, Amazed in Burning Dreams", Roberta on the Arts, November 5, 2004, accessed January 30, 2016

- ↑ Ibay, Lori. "American Ballet Theatre: Repertory Program I: 'Petite Mort', 'Sechs Tanze', 'Pillar of Fire', 'Within You Without You'", Critical Dance magazine, June 2004, accessed February 13, 2016

- ↑ Ibay, Lori. "American Ballet Theatre", Critical Dance magazine, January 2005, accessed January 30, 2016

- ↑ Nutter, Tamsin. "Swan Lake: American Ballet Theatre", The Arts Cure, June/July 2004, June 16, 2004, accessed February 7, 2016

- ↑ "Ballet Book Review Page". www.balletbooks.com and James White. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Copeland, p. 206.

- ↑ Anderson, Jack (2005-04-23). "Dance Review – A.B.T. Studio Company: Showcase Night for a Troupe of Performers-in-Progress". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ "Polovtsian Dances", ABT.org, 2005, accessed February 1, 2016

- ↑ Dunning, Jennifer (2006-06-17). "American Ballet Theater Presents 'Giselle' With Four Casts". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Popkin, Michael. "Mixed bill: Jorma Elo's new clothes....and then a masterpiece", Dance View Times, October 19, 2006, accessed February 14, 2016

- ↑ Segal, Lewis (2006-05-04). "Stylized swings from head to toe: American Ballet Theatre brings a bag of banging, nodding tricks to Orange County.". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- ↑ Zlokower, Roberta E. "American Ballet Theatre: Swan Lake 2006", Roberta on the Arts, July 1, 2006, accessed February 6, 2016; and Morris, Gay. "Veronika Part and Marcelo Gomes in American Ballet Theatre's Swan Lake", Danceviewtimes.com, Volume 4, No. 26, July 10, 2006, accessed February 6, 2016

- ↑ Rinehart, Lisa. "It's the shoes", Danceviewtimes.com, June 2, 2006, accessed January 30, 2016; and Lobenthal, Joel. "A Cast of Stars for Cinderella", The New York Sun, July 5, 2007, accessed January 30, 2016

- ↑ Placenti, Cecly. "American Ballet Theatre: Sleeping Beauty", Critical Dance magazine, June 8, 2007, accessed February 1, 2016

- ↑ "American Ballet Theatre Names Five Soloists". ABT.org. 2007-07-05. Retrieved 2016-01-29.

- ↑ "She's on Point: After seven years, ABT ballerina Misty Copeland becomes a soloist". Sixaholic. 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Jet. Johnson Publishing Company. 19 March 1981. pp. 64–. ISSN 0021-5996.

- ↑ Kisselgoff, Anna (1985-09-13). "Ballet Theater: Harvey in 'Giselle'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ↑ Anderson, Jack (1987-06-06). "Dance: Tudoe's 'Dark Elegies,' By Ballet Theater". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ↑ Harper, Francesca (2000-07-30). "Dance; To Europe and Back, A Dancer's Odyssey Of Self-Discovery". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ↑ Gillis, Casey (2013-05-29). "Keith Lee Dances: Former American Ballet Theatre soloist starts professional company". The News & Advance. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ↑ La Rocco, Claudia (2007-09-21). "TV Viewers Discover Dance, and the Debate Is Joined". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ↑ MacKrell, Judith (2008-04-10). "Where are our black ballerinas? Britain's ballet companies must start to look further than the white middle classes for their talent". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ↑ Goldhill, Olivia and Sarah Marsh. "Where are the black ballet dancers?", The Guardian, September 4, 2012, accessed January 31, 2016

- ↑ Kourlas, Gia (2007-05-07). "In ballet, blacks are still chasing a dream of diversity". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2008-08-25. domestic version with alternate images: Kourlas, Gia (2007-05-06). "Where Are All the Black Swans?". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-26.

- ↑ Howard, Rachel (2007-11-12). "Choreographer of moment struts multidisciplinary stuff". San Francisco Chronicle (Hearst Communications Inc.). Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ↑ Macaulay, Alastair (2007-10-25). "Looking Behind, and a Little Bit Ahead". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ↑ Macaulay, Alastair (2007-10-30). "Watching as Venerable Choreographers Stretch". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ↑ C. to C. (Close to Chuck), ABT, 2007, accessed February 2, 2016

- ↑ Lobenthal, Joel. "A Huddle of Humanity", The New York Sun, October 29, 2007, accessed February 2, 2016

- ↑ Dunning, Jennifer (2007-10-31). "All Sorts of Steps, Strutted for a Cause". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ↑ Macaulay, Alastair (2007-11-01). "Swinging Into Comedy (and Along With Sinatra)". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ↑ Sulcas, Roslyn (2007-11-06). "Odes to an Ax Murderer From New England and a Singer From Hoboken". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ↑ Sulcas, Roslyn (2008-06-11). "Flashing Capes and Other Spanish Flourishes". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ↑ Lobenthal, Joel (2008-06-19). "'The Sleeping Beauty,' Served Straight Up". The New York Sun. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ↑ Macaulay, Alastair (2008-10-22). "A Season Opener Equipped With the Greatest Generation". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ↑ Macaulay, Alastair (2008-10-29). "One-Acts Infused With Fresh Blood Reawaken a Seasoned Company". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- 1 2 3 "Play Misty for me: An ABT soloist finds her Prince". Time Out. May 14–20, 2009. Archived from the original on 2010-02-11. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- ↑ "The Listings". The New York Times. 2010-05-15. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ↑ Bloom, Julie (2009-08-25). "Arts, Briefly; American Ballet Theater to Go to Beijing". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ↑ Kourlas, Gia. "A Gala Night in Unfamiliar Territory", The New York Times, October 8, 2009, accessed February 15, 2016

- ↑ "ABT – All Ashton Program 6/30", Haglund's Heel, July 1, 2010, accessed February 7, 2010

- ↑ La Rocca, Claudia (2010-09-10). "Arabesques and Pirouettes on Parade". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- ↑ La Rocca, Claudia (2010-10-05). "Catching Choreographers in the Act: Two Creations for a Percussive Beat". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- ↑ Macaulay, Alastair (2010-12-24). "A ‘Nutcracker’ Sprouts Alter Egos". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- ↑ Kaufman, Sarah (2011-01-23). "ABT's 'Bright Stream' seamlessly blends comedy and history". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- ↑ Sangweni, Yolanda (2011-02-01). "BHM: Boundary-Breaking Black Women in Entertainment". Essence. Retrieved 2011-02-02.

- ↑ "American Ballet Theatre – Programme Two, Sadlers Wells". Ballet News. 2011-02-03. Retrieved 2011-02-03.

- ↑ Macaulay, Alastair. "A Big House, Big Names, New Twists", The New York Times, May 25, 2011, accessed February 2, 2016

- 1 2 Milzoff, Rebecca (2011-05-08). "The Muse: An ABT ballerina becomes an inspiration for Prince.". New York. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- ↑ Harss, Marina (2011-06-11). "Having Fun at the Ballet". The Faster Times. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- ↑ Macaulay, Alastair (2011-05-25). "A Big House, Big Names, New Twists". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- ↑ "Dance review: American Ballet Theatre dances 'The Bright Stream' at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion". Los Angeles Times. 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- ↑ "Dance Review: With the Matadors, Capes, Gypsies and Dancing, Who Needs a Plot?". The New York Times. 2011-05-18. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- ↑ Hermanson, Maggie (July 2011). "Misty Copeland's First Vail Adventure". Pointe Magazine. Retrieved 2011-08-15.

- ↑ Macaulay, Alastair. "Ode to Four Choreographers’ Work, With Coyness and Charm Thrown In", The New York Times, November 10, 2011, accessed February 14, 2016

- 1 2 3 Galchen, Rivka (2014-09-22). "An Unlikely Ballerina: The rise of Misty Copeland". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- ↑ Bleiberg, Laura. "Best in dance for 2012". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2013-01-12.

- ↑ "CUP Executive Leadership Program (2013)" (PDF). Council of Urban Professionals. 2013. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ↑ "A Profusion of Tiger Killers and Their Temple Maidens". The New York Times. 2012-06-15. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ Wolf, Stephanie (2011-12-04). "Alexei Ratmansky Choreographs New Firebird for ABT". Dance Informa. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- 1 2 Catton, Pia (2012-05-06). "New Wings for an Old Bird". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ "June 17 — 23". The New York Times. 2012-06-15. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ Kay, Lauren (2014-06-15). "Misty Copeland Breaks Ground at American Ballet Theatre". Backstage. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ Acocella, Joan (2012-06-25). "Bring in the Ballerinas". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ Copeland, pp. 251–55

- ↑ La Ferla, Ruth (2015-12-18). "The Rise and Rise of Misty Copeland". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ "The incredible story of ballerina who beat all the odds to become first African American to perform solo in New York for 20 Years". Daily Mail. June 3, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ↑ Boresta, Colleen (June 2013). "American Ballet Theatre: Le Corsaire". Critical Dance magazine. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ↑ Macaulay, Alastair (2013-06-05). "Byron’s Gloomy Pirate Tale, With Bikini Tutus Added: ‘Le Corsaire,’ American Ballet Theater". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- ↑ Zlokower, Roberta E. "American Ballet Theatre: Les Sylphides, Bach Partita, Gong", Roberta on the Arts, November 1, 2013, accessed January 30, 2016

- ↑ Hochman, Jerry. "American Ballet Theatre: The Tempest, Aftereffect, Bach Partita, Les Sylphides, Clear, Gong, Theme and Variations", Critical Dance, November 9, 2013, accessed January 30, 2016

- ↑ Hochman, Jerry (2013-12-21). "NY Nutcrackers: American Ballet Theatre and New York City Ballet". Critical Dance. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- ↑ "The Nutcracker: Ended 22 Dec 2013 after 9 days". NewYorkCityTheatre.com. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- ↑ Griffin, Julia (2014-08-08). "Grit and limbs propelled Misty Copeland's improbable rise through ballet's ranks". PBS. Retrieved 2014-09-04.

- ↑ Macaulay, Alastair (2014-06-01). "Love-Struck Hero in a Quandary: The Other Woman's a Real Doll: 'Coppélia' Returns to American Ballet Theater Repertory". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-09-04.

- 1 2 Phillips, Jevon (2014-06-11). "Misty Copeland: A trailblazing ballerina makes the judge's table". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- ↑ Seibert, Brian (2014-05-16). "Spain, With a Touch of Denmark: Alban Lendorf Performs in ‘Don Quixote’". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- ↑ Hochman, Jerry (2014-05-30). "American Ballet Theatre: Gala & Don Quixote: Metropolitan Opera House, New York, NY; May 12 & 14, 2014". Critical Dance. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- 1 2 Boresta, Colleen (2014-05-29). "American Ballet Theatre: Theme and Variations, Duo Concertant, Gaite Parisienne: Metropolitan Opera House, New York, NY; May 21(m), 2014". Critical Dance. Retrieved 2016-01-27.

- ↑ Seibert, Brian (2014-05-21). "The Parisian Life Beckons, Waiting to Become Unforgettable: American Ballet Theater Performs Gaîté Parisienne". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- ↑ Scherr, Apollinaire (2014-05-22). "Gaîté Parisienne, American Ballet Theatre, New York – review". Financial Times. Retrieved 2016-01-27.

- ↑ Hochman, Jerry (2014-06-17). "American Ballet Theatre: Cinderella: Metropolitan Opera House, New York, NY; June 9, 10, 2014". Critical Dance. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- ↑ Liebert, Marjorie (2014-08-01). "BWW Reviews: Misty Copeland - A Star Is Rocketing at American Ballet Theatre". Broadwayworld.com. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- ↑ "Casting Announced for Third and Fourth Weeks of ABT'S 2014 Spring Season At Metropolitan Opera House". ABT.org. 2014-05-01. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- ↑ Hochman, Jeremy. "American Ballet Theatre: La Bayadère". Critical Dance. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- ↑ Loeffler-Gladstone, Nicole. "Misty Copeland to Debut as Odette/Odile in "Swan Lake"". Pointe. Retrieved 2014-09-04.

- ↑ Jones, Deborah (2014-09-04). "Swan's maiden flight brings joy to the heart". The Australian. Retrieved 2014-09-04.

- ↑ Cooper, Michael (2014-09-30). "Three Ballet Theater Principals to Retire". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- ↑ Molzahn, Laura (2014-09-30). "ABT dancer Misty Copeland talks about roles on and off the stage". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ↑ Seibert, Brian (2014-10-30). "No Respite for the Eye as Ballet Hierarchy Meets Bach to the Tune of a Solo Violin: Ballet Theater Performs Bach Partita". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ↑ Witchel, Leigh. "Wrapped in an Enigma", Dance View Times, October 22, 2014, accessed February 15, 2016

- ↑ "ABT Brings The Nutcracker to BAM Howard Gilman Opera House, Beginning Tonight". Broadwayworld.com. 2014-12-12. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- ↑ "Kennedy Center Honors Five Extraordinary Artists", CBS, December 8, 2014, accessed January 31, 2016

- ↑ "American Ballet Theatre, The Sleeping Beauty", accessed January 27, 2016

- ↑ Kaufman, Sarah (2014-11-12). "Misty Copeland to make Swan Lake debut with Washington Ballet". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-11-22.

- ↑ "The Washington Ballet To Make Historic Debut of Swan Lake With Renowned Ballerina Misty Copeland". Ballet News. 2014-11-19. Retrieved 2014-11-22.

- ↑ Cargill, Mary. "Anniversary Presents", Dance View Times, May 14, 2015

- ↑ Macaulay, Alastair. "Othello Is Performed by the American Ballet Theater", The New York Times, May 20, 2015

- ↑ Zlokower, Roberta E. "American Ballet Theatre: Giselle 2015, and Xiomara Reyes' Farewell at ABT", Roberta on the Arts, May 27, 2015

- ↑ Kaufman, Sarah (2015-04-16). "Misty Copeland on 2015 Time 100". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2015-04-28.

- ↑ Cooper, Michael (2015-04-16). "Misty Copeland Makes the Cover of Time Magazine". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-04-28.

- ↑ "Review: American Ballet Theatre's The Sleeping Beauty", MetroSource, June 12, 2015, accessed February 4, 2016

- ↑ Macaulay, Alastair (2015-06-21). "Review: Three ‘Romeo and Juliet’ Performances, Including Julie Kent’s Farewell". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- 1 2 Macaulay, Alastair (2015-06-25). "Review: Misty Copeland Debuts as Odette/Odile in Swan Lake". The New York Times. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ↑ Noveck, Jocelyn (2015-06-25). "A sense of history at American Ballet Theater as Misty Copeland debuts Swan Lake in New York". U.S. News & World Report. Associated press. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ↑ Watts, Heather (July 2015). "How Ballerina Misty Copeland Became A.B.T.'s First African-American Swan Queen". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ↑ Catton, Pia (2015-06-25). "Misty Copeland Takes the Stage in Swan Lake: American Ballet Theatre soloist adds her own flourish to the role of Odette/Odile". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ↑ Bailey, Alyssa (2015-06-26). "Watch Misty Copeland Make Her Stunning Debut In Swan Lake". Elle. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- ↑ Catton, Pia (30 June 2015). "Misty Copeland Promoted to Principal Dancer at American Ballet Theatre". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ↑ Noveck, Jocelyn. "Misty Copeland named first black female principal at ABT", Associated Press, June 30, 2015. Arthur Mitchell is credited as the first dancer to break the color barrier as a male principal dancer with New York City Ballet in 1962, and Desmond Richardson did the same at ABT in 1997.

- ↑ "For Black Principal Dancers, Rarefied Air". The New York Times. June 30, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2016.

- ↑ "A Ballerina's Tale – Official Trailer ... Sundance Selects", IFC Films, at 0:29, September 4, 2015, accessed January 31, 2016; see also "American Ballet Theatre Fall Season", New York Latin Culture, October 2015, accessed February 7, 2016

- ↑ Cooper, Michael (2015-07-05). "Misty Copeland of American Ballet Theater to Join On the Town". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- ↑ Song, Jean (2015-07-06). "Misty Copeland seeks new challenge in Broadway debut". CBS News. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- ↑ Kourlas, Gia (2015-08-26). "Misty Copeland Makes Her Broadway Debut in On the Town". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- ↑ Marks, Peter (2015-08-26). "Misty Copeland brings star power to On the Town". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- ↑ Quinn, Dave (2015-08-27). "Misty Copeland Makes Glorious Broadway Debut in On the Town". WNBC. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- ↑ Scheck, Frank (2015-08-26). "On the Town: Theater Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- ↑ "American Ballet Theatre Sets Dancers for 2015 Fall Season at Koch Theatre". BroadwayWorld.com. 2015-07-28. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- ↑ Blackmore-Dobbyn, Andrew. "Powerful Program of Iconic Works at American Ballet Theater", BachTrack.com, 25 October 2015

- ↑ Harss, Marina. "American Ballet Theatre: After You, Le Spectre de la Rose, Valse Fantaisie, The Green Table, Valse Fantaisie, Company B", DanceTabs.com, October 25, 2015

- ↑ Hochman, Jerry. "Marcelo Gomes' AfterEffect is a winner all round", Critical Dance, October 30, 2015, accessed February 2, 2016

- ↑ "Casting Announced for ABT's The Nutcracker at Segerstrom Center This Winter". Broadwayworld.com. 2015-08-18. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- ↑ "Press Release announcing The Sleeping Beauty, The Kennedy Center, January 14, 2016

- ↑ Haithman, Diane (2009-05-02). "Prince and pointe shoes: ABT soloist dishes about video". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-04-16.

- ↑ Cohen, Stefanie (2010-12-26). "Prince finds a ballet muse". New York Post. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- ↑ "Close to Misty". California Chronicle. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- ↑ "Prince Plays the Classics & Debuts a New Song!". Turner Broadcasting System, Inc. 2011-04-14. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- ↑ "Misty Copeland On 'A Day In The Life' (Video)". Hulu. Retrieved 2011-09-08.

- ↑ "Morgan Spurlock 'A Day In The Life': Original Series Premieres On Hulu (Video)". The Huffington Post. 2011-08-17. Retrieved 2011-09-08.

- ↑ Price, Robyn Carolyn (2013-10-09). "Misty Copeland: The Audacity of Hope ... the Story of a Black Ballerina". Vogue Italia. Retrieved 2013-10-10.

- ↑ Phillips, Jevon (2014-06-11). "Misty Copeland: A trailblazing ballerina makes the judge's table". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ↑ Yamato, Jen (2014-08-14). "'Blind Side' Meets Ballet: New Line Eyes Biopic Of Dance Star Misty Copeland". Deadline.com. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- ↑ Goldberg, Lesley (2014-11-18). "Misty Copeland Docuseries Among Oxygen Development Slate (Exclusive)". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2014-11-22.

- ↑ Frank, Priscilla (2014-11-20). "Ballerina Of Our Dreams Misty Copeland Is Getting a Reality Show". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2014-11-22.

- ↑ Mogilevskaya, Regina (2015-04-20). "Tribeca Film Festival Review: Nelson George's "A Ballerina's Tale"". Blouin Art Info International. Retrieved 2015-04-28.

- ↑ "Exclusive Trailer Debut: The Misty Copeland Documentary A Ballerina’s Tale". Vanity Fair. 2015-09-04. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- ↑ Ziv, Stav (February 3, 2016). "A Ballerina’s Tale: Misty Copeland Documentary to Air on PBS". Newsweek. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ↑ Ziv, Stav (February 8, 2016). "Review 'A Ballerina's Tale' follows Misty Copeland's incredible rise in the ballet world". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Misty Copeland". CBS News. 2015-05-10. Retrieved 2015-05-11.

- ↑ Shattuck, Kathryn (2015-05-10). "What's on TV Sunday". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-05-11.

- ↑ "Presenters Announced For 2015 Tony Awards". WCBS. 2015-05-28. Retrieved 2015-06-30.

- ↑ Hyland, Véronique (2015-08-05). "Amal Clooney, FKA Twigs, Misty Copeland Make Vanity Fair's Best-Dressed List". New York. Retrieved 2015-08-06.

- ↑ Waxman, Olivia B. (2015-10-06). "Watch Misty Copeland and Yo-Yo Ma Perform on The Late Show With Stephen Colbert". Time. Retrieved 2015-10-08.

- ↑ "ABT's Copeland, Lane Win Annenberg Fellowships". The New York Sun. 2008-07-15. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ↑ "News". Dancing Times.

- ↑ "Misty Copeland: Principal Dancer, American Ballet Theatre, accessed January 27, 2016

- ↑ Fuller, Jaime (2014-04-24). "President Obama added basketball players, a ballerina and a celebrity chef to his administration today". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-05-08.

- ↑ Isgur, David (2014-11-03). "Groundbreaking Ballet Star Misty Copeland to Teach a Master Class and Receive an Honorary Degree". Hartford.edu. University of Hartford. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- ↑ Poisson, Cloe (2014-11-09). "Misty Copeland: A Moving Success Story". Hartford Courant. Retrieved 2016-02-09.

- ↑ Stahl, Jennifer and Wendy Perron, Katie Rolnick, Lauren Kay, Laura Cappelle. "Dance Magazine Awards 2014". Dance Magazine. Retrieved 2014-12-10.

- ↑ Italie, Leanne (2015-10-29). "Glamour's Women of the Year: Witherspoon, Jenner, Copeland". Yahoo! Sports. Associated Press. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- ↑ Morris, Alex (2015-10-29). "Ballerina Misty Copeland on Breaking Barriers, Loving Her Strong Body, and Realizing Her Dreams". Glamour. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- ↑ Davis, Dimity McDowell. "2015 IMPACT25 Influencer: Misty Copeland", ESPN, December 7, 2015

- ↑ La Ferla, Ruth. "The Rise and Rise of Misty Copeland", The New York Times, December 18, 2015

- ↑ "Misty Copeland Targets an Untapped Market with New Line M By Misty". Jones. 2011-12-12. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- ↑ Wilson, Julee (2012-11-13). "Misty Copeland, American Ballet Theatre Ballerina, Creates Stunning 2013 Calendar (Photos)". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2012-11-15.

- ↑ Cepeda, Esther (2014-05-07). "Ballerina's lonely rise inspires hope". Columbia Daily Tribune. Retrieved 2014-05-08.

- ↑ "Firebird". Random House. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

- ↑ Barone, Joshua (2015-11-18). "Misty Copeland to Write Book on Health and Fitness". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- ↑ "This is Why She Rocks". OliveCoco. 2010-12-20. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- ↑ Pathak, Shareen Pathak (2012-12-28). "See the Spot: Dr Pepper Highlights Individuals with Unique Stories". Advertising Age. Retrieved 2013-01-12.

- ↑ Catton, Pia (2013-09-12). "Dancing Toward Diversity: Misty Copeland To Be Face of Project Plié". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2013-09-14.

- ↑ "Seiko Corporation of America Signs Two New Brand Ambassadors". PR Newswire. 2015-03-18. Retrieved 2015-11-02.

- ↑ Meehan, Sarah (2014-04-23). "Under Armour to release earnings after roller coaster first quarter". Baltimore Business Journal. Retrieved 2014-05-08.

- ↑ Rovell, Darren (2014-07-31). "Under Armour bets big on a ballerina". ESPN. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ↑ Dockterman, Eliana (2014-08-01). "Watch This Inspiring Under Armour Ad Starring Ballerina Misty Copeland". Time. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ↑ Chernikoff, Leah (2014-07-31). "Proof That Misty Copeland Is the Most Badass Ballerina". Elle. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ↑ Newman, Andrew Adam (2014-07-31). "Under Armour Heads Off the Sidelines for a Campaign Aimed at Women". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ↑ "A Ballerina Who Defies the Odds: Misty Copeland". ABC News. 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2014-08-09.

- ↑ Nudd, Tim (2014-11-30). "The 10 Best Ads of 2014: Sports, comedy, PSAs and pranks: Here's the work you wish you made this year". Adweek. Retrieved 2014-12-02.

- ↑ Bryan, Bob (2015-07-23). "Under Armour attributes its explosive growth to these 3 athletes". Business Insider. Retrieved 2015-07-30.

- ↑ Howard, Hilary (2014-10-17). "Ballet Dancer Has a Day Off, but She Still Moves". The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-10-18.; and D'Amour, Zon. "New Details On Misty Copeland’s Upcoming Wedding! Guess What Celebrity She’ll Be Related To?", HelloBeautiful.com, October 13, 2015

- ↑ Greer, Carlos (2015-08-21). "Taye Diggs played matchmaker for Misty Copeland and her fiancé". New York Post. Retrieved 2015-08-23.

- ↑ "Misty Copeland Dances Onto the September Cover of 'Essence'". Essence. 2015-08-09. Retrieved 2015-08-15.

External links

- Official website

- Misty Copeland at the Internet Movie Database

- Copeland dancing in On the Town on Broadway (2015)

- "Cupcakes & Conversation with Misty Copeland". Ballet News. April 11, 2011.

- Copeland archive at Los Angeles Times

- A Day In the Life With Misty Copeland

- 55-minute version of A Ballerina's Tale, PBS (2016)

|