Mistletoe

Mistletoe is the common name for most obligate hemiparasitic plants in the order Santalales. Mistletoes attach to and penetrate the branches of a tree or shrub by a structure called the haustorium, through which they absorb water and nutrients from the host plant.

The name mistletoe originally referred to the species Viscum album (European mistletoe, of the family Santalaceae in the order Santalales); it was the only species native to Great Britain and much of Europe. A separate species, Viscum cruciatum, occurs in Southwest Spain and Southern Portugal, as well as North Africa, Australia and Asia.

Over the centuries, the term has been broadened to include many other species of parasitic plants with similar habits, found in other parts of the world, that are classified in different genera and even families — such as the Misodendraceae and the Loranthaceae.

In particular, the Eastern mistletoe native to North America, Phoradendron leucarpum, belongs to a distinct genus of the Santalaceae family. The genus Viscum is not native to North America, but Viscum album has been introduced to California.[1] European mistletoe has smooth-edged, oval, evergreen leaves borne in pairs along the woody stem, and waxy, white berries that it bears in clusters of two to six. The Eastern mistletoe of North America is similar, but has shorter, broader leaves and longer clusters of 10 or more berries.

Etymology

The word 'mistletoe' derives from the older form 'mistle', adding the Old English word tān (twig). 'Mistle' is common Germanic (Old High German mistil, Middle High German. mistel, Old English mistel, Old Norse mistil).[2] Further etymology is uncertain, but may be related to the Germanic base for 'mash'.[3]

Mistletoe groups

Parasitism has evolved at least twelve times among the vascular plants;[4] and of those, the parasitic mistletoe habit has evolved independently five times, in the Misodendraceae, Loranthaceae, and Santalaceae, including the former separate families Eremolepidaceae and Viscaceae. Although Viscaceae and Eremolepidaceae were placed in a broadly defined Santalaceae by Angiosperm Phylogeny Group II, DNA data indicate they evolved independently.

The largest family of mistletoes, the Loranthaceae, has 73 genera and over 900 species.[5] Subtropical and tropical climates have markedly more mistletoe species; Australia has 85, of which 71 are in Loranthaceae, and 14 in Santalaceae.[6]

Life cycle

Mistletoe plants grow on a wide range of host trees; they commonly reduce their growth and a large plant stunts and commonly kills the distal portion of branch it grows on. A heavy infestation may kill the entire host plant. Viscum album successfully parasitizes more than 200 tree and shrub species.

Technically, all mistletoe species are hemiparasites, because they do perform at least a little photosynthesis for at least a short period of their life cycle. However, this is academic in some species whose contribution is very nearly zero. For example, some species, such as Viscum minimum, that parasitize succulents, commonly species of Cactaceae or Euphorbiaceae, grow largely within the host plant, with hardly more than the flower and fruit emerging. Once they have germinated and attached to the circulatory system of the host, their photosynthesis reduces so far that it becomes insignificant.[7]

Most of the Viscaceae bear evergreen leaves that photosynthesise effectively, and photosynthesis proceeds within their green, fleshy stems as well. Some species, such as "Viscum capense", are adapted to semi-arid conditions and their leaves are vestigial scales, hardly visible without detailed morphological investigation. Therefore their photosynthesis and transpiration only take place in their stems, limiting their demands on the host's supply of water, but also limiting their intake of carbon dioxide for photosynthesis. Accordingly their contribution to the host's metabolic balance becomes trivial and the idle parasite may become quite yellow as it grows, having practically given up photosynthesis.[7]

At another extreme other species have vigorous green leaves. Not only do they photosynthesize actively, but a heavy infestation of mistletoe plants may take over whole host tree branches, sometimes killing practically the entire crown and replacing it with their own growth. In such a tree the host is relegated purely to the supply of water and mineral nutrients and the physical support of the trunk. Such a tree may survive as a Viscum community for years; it resembles a totally unknown species unless one examines it closely, because its foliage does not look like that of any tree. An example of a species that behaves like that is Viscum continuum.[7]

A mistletoe seed germinates on the branch of a host tree or shrub, and in its early stages of development it is independent of its host. It commonly has two or even four embryos, each producing its hypocotyl, that grows towards the bark of the host under the influence of light and gravity, and potentially each forming a mistletoe plant in a clump. Possibly as an adaptation to assist in guiding the process of growing away from the light, the adhesive on the seed tends to darken the bark. On having made contact with the bark, the hypocotyl, with only a rudimentary scrap of root tissue at its tip penetrates it, a process that may take a year or more. In the mean time the plant is dependent on its own photosynthesis. Only after it reaches the host's conductive tissue can it begin to rely on the host for its needs. Later it forms a haustorium that penetrates the host tissue and takes water and nutrients from the host plant.[7]

Species more or less completely parasitic include the leafless quintral, Tristerix aphyllus, which lives deep inside the sugar-transporting tissue of a spiny cactus, appearing only to show its tubular red flowers,[8] and the genus Arceuthobium (dwarf mistletoe; Santalaceae) which has reduced photosynthesis; as an adult, it manufactures only a small proportion of the sugars it needs from its own photosynthesis, but as a seedling actively photosynthesizes until a connection to the host is established.

Some species of the largest family, Loranthaceae, have small, insect-pollinated flowers (as with Santalaceae), but others have spectacularly showy, large, bird-pollinated flowers.

Most mistletoe seeds are spread by birds that eat the 'seeds' (in actuality drupes). Quite a range of birds feed on them, of which the mistle thrush is the best-known in Europe, the Phainopepla in southwestern North America, and Dicaeum of Asia and Australia. Depending on the species of mistletoe and the species of bird, the seeds are regurgitated from the crop, excreted in their droppings, or stuck to the bill, from which the bird wipes it onto a suitable branch. The seeds are coated with a sticky material called viscin. Some viscin remains on the seed and when it touches a stem, it sticks tenaciously. The viscin soon hardens and attaches the seed firmly to its future host, where it germinates and its haustorium penetrates the sound bark.[9]

Specialist mistletoe eaters have adaptations that expedite the process; some pass the seeds through their unusually shaped digestive tracts so fast that a pause for defecation of the seeds is part of the feeding routine. Others have adapted patterns of feeding behavior; the bird grips the fruit in its bill and squeezes the sticky-coated seed out to the side. The seed sticks to the beak and the bird wipes it off onto the branch.[10]

Biochemically, viscin is a complex adhesive mix containing cellulosic strands and mucopolysaccharides.[11]

Once a mistletoe plant is established on its host, it usually is possible to save a valuable branch by pruning and judicious removal of the wood invaded by the haustorium, if the infection is caught early enough. Some species of mistletoe can regenerate if the pruning leaves any of the haustorium alive in the wood.[12][13]

Ecological importance

Mistletoe was often considered a pest that killed trees and devalued natural habitats, but was recently recognized as an ecological keystone species, an organism that has a disproportionately pervasive influence over its community.[14] A broad array of animals depend on mistletoe for food, consuming the leaves and young shoots, transferring pollen between plants and dispersing the sticky seeds. In western North America their juicy berries are eaten and spread by birds (notably Phainopepla, or silky-flycatcher). When eaten, some seeds pass unharmed through their digestive systems; if the birds’ droppings happen to land on a suitable branch, the seeds may stick long enough to germinate. As the plants mature, they grow into masses of branching stems which suggest the popular name "witches’ brooms". The dense evergreen witches' brooms formed by the dwarf mistletoes (Arceuthobium species) of western North America also make excellent locations for roosting and nesting of the northern spotted owl and the marbled murrelet. In Australia the diamond firetail and painted honeyeater are recorded as nesting in different mistletoes. This behavior is probably far more widespread than currently recognized; more than 240 species of birds that nest in foliage in Australia have been recorded nesting in mistletoe, representing more than 75% of the resident birds.

A study of mistletoe in junipers concluded that more juniper berries sprout in stands where mistletoe is present, as the mistletoe attracts berry-eating birds which also eat juniper berries.[15] Such interactions lead to dramatic influences on diversity, as areas with greater mistletoe densities support higher diversities of animals. Thus, rather than being a pest, mistletoe can have a positive effect on biodiversity, providing high quality food and habitat for a broad range of animals in forests and woodlands worldwide.

Cultural references

Mistletoe is relevant to several cultures. It is associated with Western Christmas as a decoration, under which lovers are expected to kiss. Mistletoe played an important role in Druidic mythology in the Ritual of Oak and Mistletoe.

In Norse Mythology, Loki tricked the blind god Hodur into murdering Balder with an arrow made of Mistletoe, being the only plant to which Balder was vulnerable. Some versions of the story have mistletoe becoming a symbol of peace and friendship to compensate for its part in the murder.[16]

Mistletoe continued to be associated with fertility and vitality through the Middle Ages, and by the 18th century it had also become incorporated into Christmas celebrations around the world. The custom of kissing under the mistletoe is referred to in late 18th century England:[17] the serving class of Victorian England is credited with perpetuating the tradition.[18] The tradition dictated that a man was allowed to kiss any woman standing underneath mistletoe, and that bad luck would befall any woman who refused the kiss.[19][20] One variation on the tradition stated that with each kiss a berry was to be plucked from the mistletoe, and the kissing must stop after all the berries had been removed.[18][20]

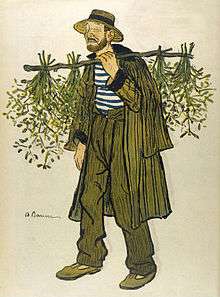

Gallery

-

European mistletoe on an apple tree in Essex, England

-

Mistletoe bush on a Eucalyptus tree

-

Mistletoe attached to Eucalyptus host

-

Fruits

-

Red mistletoe, New Zealand

-

Mistletoe in San Bernardino Mountains

-

Mistletoe berries in Wye Valley

-

Heavy load of mistletoe on apple tree in Franche-Comté.

-

Mistletoe in abundance in Wye Valley

-

Mistletoe in North Central Texas

-

Desert mistletoe on a palo verde tree in southern Arizona.

See also

References

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. 2009. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 28 August 2009). National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70874-4490 USA

- ↑ Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. "Deutsches Wörterbuch". Woerterbuchnetz. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd edition, December 2000

- ↑ JH Westwood, JI Yoder, MP Timko, CW dePhamphilis (2010) The evolution of parasitism in plants. Trends Plant Sci 15:227-235

- ↑ WS Judd, CS Campbell, EA Kellogg, PF Stevens & MJ Donaghue (2002) Plant systematics: a phylogenetic approach. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland Massachusetts, USA. ISBN 0-87893-403-0

- ↑ B.A. Barlow (1983) A revision of the Viscaceae of Australia. Brunonia 6, 25–58.

- 1 2 3 4 Visser, Johann (1981). South African parasitic flowering plants. Cape Town: Juta. ISBN 0-7021-1228-3.

- ↑ Susan Milius, "Botany under the Mistletoe" Science News' 158.26/27 (December 2000:412).

- ↑ Zulu Journal. University of California Press. pp. 114–. GGKEY:5QX6L53RH1U. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ↑ Maurice Burton; Robert Burton (2002). International Wildlife Encyclopedia. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 869–. ISBN 978-0-7614-7266-7. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ↑ International Society for Horticultural Science. Section for Ornamental Plants; International Society for Horticultural Science. Commission on Landscape and Urban Horticulture; International Society for Horticultural Science. Working Group on New Ornamentals (2009). Proceedings of the VIth International Symposium on New Floricultural Crops: Funchal, Portugal, June 11–15, 2007. International Society for Horticultural Science. ISBN 978-90-6605-200-0. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ↑ "Mistletoe". University of California - Davis. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ↑ Torngren, T. S., E. J. Perry, and C. L. Elmore. 1980. Mistletoe Control in Shade Trees. Oakland: Univ. Calif. Agric. Nat. Res. Leaflet 2571

- ↑ David M. Watson, "Mistletoe-A Keystone Resource in Forests and Woodlands Worldwide" Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 32 (2001:219–249).

- ↑ Susan Milius, "Mistletoe, of All Things, Helps Juniper Trees" Science News 161.1 (January 2002:6).

- ↑ "Norse, Greek & Roman mistletoe traditions". The Mistletoe Pages. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ "The pendant mistletoe, hung up to view/ Reminds the youth, the duty youth should do:/ While titt'ring maidens, to enhance their wishes /Entice the men to smother them with kisses..." The Times (London England) 24 December 1787 p.3 (poem),The Approach of Christmas

- 1 2 "Why do we kiss under the mistletoe?". History.com. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- ↑ Beam, Christopher. "What's the deal with mistletoe?". slate.com. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

- 1 2 Norton, Lily. "Pucker up! Why do people kiss under the mistletoe?". livescience.com. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mistletoe. |

| Look up mistletoe in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1921 Collier's Encyclopedia article Mistletoe. |

- About mistletoe

- Parasitic Plant Connection. See families Misodendraceae, Loranthaceae, Santalaceae, and Viscaceae

- Introduction to Parasitic Flowering Plants by Nickrent & Musselman

- Phoradendron serotinum images at bioimages.vanderbilt.edu

- Scientific Studies, Research and Clinical Trials on Mistletoe Treatment in Cancer

- Deck the halls with wild, wonderful mistletoe, West Virginia Department of Agriculture

-

"Mistletoe". Encyclopædia Britannica 16 (9th ed.). 1883.

"Mistletoe". Encyclopædia Britannica 16 (9th ed.). 1883. -

"Mistletoe". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

"Mistletoe". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.