Missing women of Asia

The phenomenon of the missing women of Asia is a shortfall in the number of women in Asia relative to the number that would be expected if there were no sex-selective abortion and female infanticide and if the newborn of both sexes received similar levels of health care and nutrition.

Technologies that enable prenatal sex selection have been commercially available since the 1970s. The phenomenon was first noted by the Indian Nobel Prize–winning economist Amartya Sen in an essay in The New York Review of Books in 1990,[1] and expanded upon in his subsequent academic work. Sen originally estimated that more than a hundred million women were "missing" (in the sense that their potential existence had been eliminated either through sex selective abortion, infanticide or inadequate nutrition during infancy).

The disparity has also been found in the Chinese and Indian diasporas in the United States, albeit to a far lesser degree than in Asia. An estimated 2000 Chinese and Indian female fetuses were aborted between 1991 and 2004, and a shortage can be traced back as far as 1980.[2]

Some countries in the former Soviet Union also saw declines in female births after the revolutions of 1989, particularly in the Caucasus region.[3]

Originally some other economists, notably Emily Oster, questioned Sen's explanation, and argued that the shortfall was due to higher prevalence of the hepatitis B virus in Asia compared to Europe, while her later research has established that the prevalence of hepatitis B cannot account for more than an insignificant fraction of the missing women.[4] As a result, Sen's explanation for the phenomenon is still the most accepted one.

|

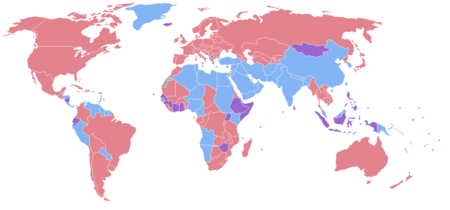

Countries with more females than males

Countries with an approximate equal number of males and females

Countries with more males than females

No data |

The problem and prevalence

According to Sen, women allegedly make up the majority of the world's population, even though this is not the case throughout every country. While there are typically more women than men in European and North American countries (at around 0.98 men to 1 woman for most of them, in number of males for each female), the sex ratio of developing countries in Asia, as well as the Middle East, is much higher (in number of males for each female). This runs contrary to research that females tend to have better survival rates than males, given the same amount of nutritional and medical attention.[1][5]

In China, the ratio of men to women is 1.06, far higher than most countries. The ratio is much higher than that for those born after 1985, when ultrasound technology became widely available. Translating this into an actual number means that in China alone there are 50 million women "missing" - that should be there but are not. Adding up similar numbers from South and West Asia results in a number of "missing" women higher than 100 million.[1] According to Sen, "These numbers tell us, quietly, a terrible story of inequality and neglect leading to the excess mortality of women."[1]

Causes

Sen's original argument

Sen argued that the disparity in sex ratio across eastern Asian countries like India, China, and Korea when compared to North America and Europe, as seen in 1992, could only be explained by deliberate nutritional and health deprivations against female children. These deprivations are caused by cultural mechanisms, such as traditions and values, that vary across countries and even regionally within countries.[6] Due to the inherent bias toward male children in many of these countries, female children, if born despite many instances of sex-selective abortion, are born without the same sense of priority given to men. This is especially true in the medical care given to men and women, as well as prioritizing who gets food in less privileged families, leading to lower survival rates than if both genders were treated equally.[7]

Perspectives from female adults

According to Sen's cooperative conflict model,[8] the relations within the household are characterized by both cooperation and conflict: cooperation in the addition of resources and conflict in the division of resources among the household. These intra-household processes are influenced by perceptions of one's self-interest, contribution and welfare. One's fall back position is the situation for each party once the bargaining process has failed and also determines the ability of each party to survive outside of the relationship.[8]

Typically, the fall-back position for men who have land ownership rights, more economic opportunities and less care work related to children is better than a woman's fall-back position, who is dependent on her husband for land and income. According to this framework, when women lack a perception of personal interest and have greater concern for their family welfare gender inequalities are sustained. Sen argues that women's lower bargaining power in household decision contributes to the shortfall in female populations across eastern Asia.[8]

Perspectives from female children

Sen suggests that the care and nutrition female children receive may be positively correlated to the outside earning power and sense of contribution of women when compared to men. Not all forms of outside work contribute equally to increasing women's bargaining power in the household as Sen also points out that the kind of outside work women do has bearing on their entitlements and fall-back position. Women can be doubly exploited as in the case of the work done by lace-makers in Narsapur, India. Since the work was done in the home it was perceived as only supplementary to male work rather than gainful outside contribution.[8]

Males are more prized in these regions where they are looked upon as more economically productive, and as women become more economically productive themselves it may alter the view that female children cannot grow up to be economically productive as well, and may increase girls chances of surviving to birth and receiving the care and attention during childhood that they need.[9]

Perspectives outside of southeast Asia

Sen also notes the difference in Sub-Saharan Africa, where a woman is generally able to earn income from outside the home and thereby increase her contributions to her household as well as the overall view of the value of being a woman. Sen implies that it is a woman's opportunity to participate in the labor force that affords her more bargaining power within the home. Sen is hopeful that policies aimed to address education, women's property rights as well as economic rights and opportunities outside the home may improve the missing women situation and fight the stigma attached to female children.[9]

Sen's contention about gainful work outside the home has led to some debates. Berik and Bilginsoy researched Sen's premise that women's economic opportunities outside of the home will diminish the disparity in the sex ratio in Turkey. They found that as women participated more in the work force and maintained their unpaid labor the sex ratio disparity grew, contrary to Sen's original prediction.[10]

Sen's amended theory

Later, in 2001, in response to the preliminary findings of the Indian Census, Sen amended his original argument to account for a new kind of discrimination against women being found in various states of India. Women's increased educational attainment was associated with the rise in the population sex ratio of India.[6]

Similarly, as women were able to afford better healthcare and economic opportunities outside the home they increasingly had access to healthcare facilities including ultrasound treatment. This, according to Sen, is actually exacerbating the problem, allowing parents to screen out the unwanted female fetuses before they are even born. He referred to this inequality as "high tech sexism." Sen concluded that these biases against women were so "entrenched" that even relative economic improvements in the lives of households have only enabled these parents a different avenue for rejecting their female children. Sen then argued that instead of just increasing women's economic rights and opportunities outside the home a greater emphasis needed to be placed on raising consciousness to eradicate the strong biases against female children.[6]

One reason for parents, even mothers, to avoid daughters is the traditional patriarchal culture in the countries where the elimination of females takes place. As parents grow older they can expect much more help and support from their independent sons, than from daughters, who after getting married become in a sense property of their husbands' families, and, even if educated and generating significant income, have limited ability to interact with their natal families. Women are also often practically unable to inherit real estate, so a mother-widow will lose her family's (in reality her late husband's) plot of land and become indigent if she had had only daughters. Poor rural families have meager resources to distribute among their children, which reduces the opportunity to discriminate against girls.[11]

Hepatitis B virus explanation

In her PhD dissertation at Harvard, Emily Oster argued that Sen's hypothesis did not take account of the different rates of prevalence of the Hepatitis B virus between Asia and other parts of the world.[12] Regions with higher rates of Hepatitis B infection tend to have higher ratios of male to female births for biological reasons which are not yet well understood, but which have been extensively documented.

While the disease is fairly uncommon in US and Europe, it is endemic in China and very common in other parts of Asia. Oster argued that this difference in disease prevalence could account for about 45% of the supposed "missing women", and even as high as 75% of the ones in China. Furthermore, Oster showed that the introduction of a Hepatitis B vaccine had a lagged effect of equalizing the gender ratio towards what one would expect if other factors did not play a role.[12]

Subsequent research

Oster's challenge was met with counter arguments of its own as researchers tried to sort out the available data and control for other possible confounding factors. Avraham Ebenstein questioned Oster's conclusion based on the fact that among first born children the sex ratio is close to the natural one. It is the skewed female-male ratios among second and third born children that account for the bulk of the disparity. In other words, if Hepatitis B was responsible for the skewed ratio then one would expect it to be true among all children, regardless of birth order.

However, the fact that the skewness arose less among the later born than among the first born children, suggested that factors other than the disease were involved.[13]

Das Gupta pointed out that the female-male ratio changed in relation to average household income in a way that was consistent with Sen's hypothesis but not Oster's. In particular, lower household income eventually leads to a higher boy/girl ratio. Furthermore, Das Gupta documented that the gender birth order was significantly different conditional on the sex of the first child.

If the first child was male, then the sex of the subsequent children tended to follow the regular, biologically determined sex pattern (boys born with probability 0.512, girls born with probability 0.488). However, if the first child was female, the subsequent children had a much higher probability of being male, indicating that conscious parental choice was involved in determining the sex of the child. Neither of these phenomena can be explained by the prevalence of Hepatitis B.

They are, however, consistent with Sen's contention that it is purposeful human action - in the form of selective abortion and perhaps even infanticide and female infant neglect - that is the cause of the skewed gender ratio.[14]

Oster's theory refuted

Part of the difficulty in discerning between the two competing hypotheses was the fact that while the link between Hepatitis B and a higher likelihood of male birth had been documented, there was little information available on the strength of this link and how it varied by which of the parents were the carriers. Furthermore, most prior medical studies did not use a sufficiently high number of observations to convincingly estimate the magnitude of the relationship.

However, in a 2008 study published in the American Economic Review, Lin and Luoh utilized data on almost 3 million births in Taiwan over a long period of time and found that the effect of maternal Hepatitis B infection on the probability of male birth was very small, about one quarter of one percent.[15] This meant that the rates of Hepatitis B infection among mothers could not account for the vast majority of missing women.

The remaining possibility was that it was the infection among fathers that could lead to a skewed birth ratio. However, Oster, together with Chen, Yu and Lin, in a follow up study to Lin and Luoh examined a data set of 67,000 births (15% of whom were Hepatitis B carriers) and found no effect of infection on birth ratio for either the mothers or fathers. As a result, Oster retracted her earlier hypothesis.[4] This retraction was praised by the John Bates Clark Medal winner and Freakonomics author Steven Levitt for its honesty.[16]

Other diseases

In a 2008 study, Anderson and Ray claim that other diseases may explain the "excess female mortality" across Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.[17] 37 to 45% of the missing women in China can be traced to pre-birth and infancy stage termination factors, whereas only around 11% of India's missing women were caused by similar factors, pointing to the fact that the loss is spread across different ages. They find that by and large, the main cause for female deaths in India is cardiovascular disease. "Injuries" is the number two cause of female deaths in India. Both of these causes are far greater than maternal mortality and abortion of fetuses, though "Injuries" may be directly related to gender discrimination.[17]

Their findings for China also attribute missing women of older ages to cardiovascular and other non-communicable diseases, accounting for a large portion of excess female deaths. However, the largest bracket of missing women is in the 0-4 age group, suggesting discrimination factors at work in accordance to Sen's original theories.[17]

In sub-Saharan Africa, in contrast to Sen's contention and average statistics, Anderson and Ray find a large amount of women are missing.[6] Sen used the sex ratio of 1.022 for sub-Saharan Africa in work done in 2001, to avoid comparing advanced countries to developing ones. Like Sen believed, in their study they find no evidence to impute the missing women to birth discrimination such as sex-selective abortions or neglect. To account for high number of young women missing they discovered that HIV/AIDS was the main cause, surpassing malaria and maternal mortality. Anderson and Ray estimated an annual excess female death rate 600,000 due to HIV/AIDS alone. The age groups with the highest numbers of missing women were the 20- to 24- and 25- to 29-year-old ranges. The high prevalence of HIV/AIDS seems to suggest, according to Anderson and Ray, an imbalance in women's access to healthcare as well as different attitudes about sexual and cultural norms.[17]

In an article in 2008, Eileen Stillwaggon, showed that higher rates of HIV/AIDS are the consequence of deep-rooted gender inequalities in sub-Saharan Africa. In countries where women cannot own property they are in a more precarious fall-back position, having less bargaining power to "insist on safe sex without risking abandonment" by their husbands.[18] She claims that a person's vulnerability to HIV depends on their overall health, and as misinformed practices, such as the belief that having sex with a female virgin will cure a male of AIDS, dry sex, and household activities that expose women to diseases contribute to weakening women's immune systems which leads to higher HIV mortality rates. Stillwaggon argues for increased focus on sanitation and nutrition rather than just abstinence or safe sex. As women become healthier the chances of an infected female transmitting HIV to a male partner decline significantly.[18]

Natural causes to high or low human sex ratio

Other scholars question the assumed normal sex ratio, and point to a wealth of historical and geographical data that suggest sex ratios vary naturally over time and place, for reasons not properly understood. William James and others[19][20] suggest that conventional assumptions have been:

- there are equal numbers of X and Y chromosomes in mammalian sperms

- X and Y stand equal chance of achieving conception

- therefore equal number of male and female zygotes are formed, and that

- therefore any variation of sex ratio at birth is due to sex selection between conception and birth.

James cautions that available scientific evidence stands against the above assumptions and conclusions. He reports that there is an excess of males at birth in almost all human populations, and the natural sex ratio at birth is usually between 102 to 108. However the ratio may deviate significantly from this range for natural reasons such as early marriage and fertility, teenage mothers, average maternal age at birth, paternal age, age gap between father and mother, late births, ethnicity, social and economic stress, warfare, environmental and hormonal effects.[19][21] This school of scholars support their alternate hypothesis with historical data when modern sex-selection technologies were unavailable, as well as birth sex ratio in sub-regions, and various ethnic groups of developed economies.[22][23] They suggest that direct abortion data should be collected and studied, instead of drawing conclusions indirectly from sex ratio as Sen and others have done.

James's hypothesis is supported by historical birth sex ratio data before technologies for ultrasonographic sex-screening were discovered and commercialized in the 1960s and 1970s, as well by reversed sex ratios currently observed in Africa. Michel Garenne reports that many African nations have, over decades, witnessed birth sex ratios below 100, that is more girls are born than boys.[24] Angola, Botswana and Namibia have reported birth sex ratios between 94 to 99, which is quite different than the presumed 104 to 106 as natural human birth sex ratio.[25] John Graunt noted that in London over a 35-year period in the 17th century (1628–1662),[26] the birth sex ratio was 1.07; while Korea's historical records suggest a birth sex ratio of 1.13, based on 5 million births, in 1920s over a 10-year period.[27]

Measurement issues

Sen originally based his calculations on the average sex ratio of Europe and North America in order to calculate the number of missing women, assuming that in these countries men and women receive equal care. Using population data from several countries and the disparity between their respective sex ratios and the standard he was able to conclude that over 100 million women were missing.[28]

This method has been disputed by other researchers. Coale noted other factors that lead to “high masculinity” such as male workers migrating from rural to urban regions, immigration, and world war. In studying census data across the states of India spanning from the late 1950s through the mid 1980s Coale noticed the effect of traditions being stronger in some states than others relating to discriminatory treatment of female children. In Coale's estimation he used a sex ratio of 1.059, arriving at an estimate of 60 million missing women, much lower than Sen's original estimate.[29]

Klasen and Wink conducted a study in 2002 with updated census data ten years after Sen's 1992 publication. Overall they found trends that showed that while West Asia, North Africa and most of South Asia saw more equal sex ratios, China's and South Korea's ratios worsened. Sex-selective abortions were given as reasons for the lack of improvement in India and China while women's growing educational and employment opportunities were cited as reasons for the ratio improvement in other previously low ratio countries.[30]

Anderson and Ray approach computing the number of missing women by relying on comparing relative death rates of females to males in developed countries to that of the country in question.[31]

Under-reporting

Some evidence suggests that in Asia, especially in China with its one-child policy, additional fertility behavior, infant deaths, and female birth information may be hidden or not reported. Instead of policy expanding women's opportunities for gainful employment policy, from 1979 onward the one-child policy has added upon the son preference causing the largest number of missing women in any country.[32] As parents are eager to have sons and are allowed only one child, some first born females are not reported with the hope that their next child will be a son.[33][34] Surviving children who live unreported suffer by not having access to health insurance, lower chances receiving and education and often live with the feeling that they are a burden to their families.

Female abduction and sale

Evidence has shown that number of missing women may be due to other reasons than sex selective abortions or female migrant work. Specifically, female babies, girls and women have been preyed upon by human traffickers. In China families are less willing to sell male babies even though they carry a higher price in the trade. Females born exceeding the one-child policy can be sold to wealthier families while the parents claim selling their female baby is better than other alternatives.[35]

Overseas adoption services for Chinese children have been involved in baby trafficking to reap the profits of donations from foreign adopters.[36] One study notes that between 2002 and 2005 approximately 1000 trafficked babies were placed with adopting parents, each baby costing $3000.[37] To keep up supply of orphans for adoption, orphanages and retirement homes hire women as baby traffickers.[37]

Overall, underreporting and trafficking may be too small to account for the staggering numbers of missing women across south-eastern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa though they may be related in causal factors.

Differences across countries/ states

Das Gupta observed that the preference for boys and the resulting shortage of girls was even more pronounced in the more highly developed Haryana and Punjab regions of India than in poorer areas, and also the high prevalence of this prejudice among the more educated and affluent women (mothers) there. Contrary to the conventional wisdom expectations, in India there are more missing women in developed urban areas, than in rural regions. The bias against girls is very evident among the relatively highly developed, middle-class dominated nations (Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia) and the immigrant Asian communities in the United States and Britain. Only recently and in some countries (particularly South Korea) have the development and educational campaigns begun to turn the tide, resulting in more normal gender ratios.[11]

According to Das Gupta's research done in Punjab in the 1980s, girls were not receiving inferior treatment if a girl was born as a first child in a given family, when the parents still had high hopes for obtaining a son later. Subsequent births of girls were however unwelcome, because each such birth diminished a chance of the family having a son. The more affluent and educated women would have fewer offspring, and therefore were under more acute pressure to produce a son as early as possible. As ultrasound imaging and other techniques increasingly allow early prediction of the child's sex, the more affluent families opt for an abortion, or if a girl is born, decrease her chance of survival by, for example, not providing sufficient medical care.[11]

China's regional differences have different attitudes towards the one-child policy. Urban areas have been found to be easier to enforce the policy, due to the danwei system, a generally more educated urban population – understanding that one child is easier to care for and keep healthy than two. In more rural areas where farming is labor-intensive and couples depend on male offspring to take care of them in old age, males children are preferred to females.[35]

Estimates of missing women

Estimates vary considerably between researchers primarily because of underlying assumptions for "normal" birth sex ratios and expected post-birth mortality rates for men and women. For example, a 2005 study estimated that over 90 million females were "missing" from the expected population in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, China, India, Pakistan, South Korea and Taiwan alone.[38] In contrast, from 1980s and 1990s data, Sen estimated 106 million missing women in Asia (exclusive of his Egypt estimates), Coale estimated 60 million as missing, while Klasen estimated 88 million missing women in China, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and West Asia.[39] These three researchers, note Klausen and Wink, find Pakistan had the world's highest % of missing girls, relative to its total pre-adult female population.[40] Guilmoto,[41] in his 2010 report, uses recent data (except for Pakistan), and estimates a much lower number of missing girls in Asian and non-Asian countries, but notes that the higher sex ratios in numerous countries have created a gender gap - shortage of girls - in the 0–19 age group.

| Country | Gender gap 0-19 age group (2010)[41] | % females[41] |

|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 265,000 | 3 |

| Bangladesh | 416,000 | 1.4 |

| China | 25,112,000 | 15 |

| India | 12,618,000 | 5.3 |

| Nepal | 125,000 | 1.8 |

| Pakistan | 206,000 | 0.5 |

| South Korea | 336,000 | 6.2 |

| Singapore | 21,000 | 3.5 |

| Vietnam | 139,000 | 1 |

Consequences

Some research has also noted that in the mid-1990s a reverse began in the observed trends in the regions of Asia where originally the male/female ratios were high. In line with the studies of Das Gupta described above, as income increases the bias in the sex ratio towards boys decreases.

Societal health

Female discrimination and neglect is not just impacting girls and women. Sen described the effects of female malnutrition and other forms of discrimination on men's health.[6] As pregnant women suffer from nutritional neglect the fetus suffers, leading to low birth weight for male as well as female babies. Medical studies have found a close relationship to low birth weight and cardiovascular diseases at later stages in life.[6] While underweight female babies are at risk for continuing undernourishment, ironically, Sen points out that even decades after birth, "men suffer disproportionately more from cardiovascular diseases."[6]

With high per capita income growth in many parts of India and China during the late 1990s and the 2000s, male/female ratios have begun shifting towards "normal" levels.[42][43] However, for India and China, this appears to be due to a fall in adult female mortality rates, relative to male adults, rather than a change in the sex ratio among children and newborns.

In general, these conditions amount to widespread deprivations of women across East and South Asia. According to Nussbaum's Capabilities Approach, as millions of females are discriminated against they are being deprived of their essential capabilities to such as life, bodily health and bodily integrity, among others. According this framework, policy should focus on increasing women's capabilities even at the cost of changing long held traditions.[44]

Missing brides

Some have speculated that the disparity in the sex ratio may have an impact on the marriage market in such a way that may turn the tide of missing women.[45] David De La Croix and Hippolyte d'Albis developed the Missing Bride Index and a mathematical model showing that over time, as rich and affluent families continue to abort female babies and raise male children and as less wealthy families have girls, more males will be more affluent and the prospects for women to marry will increase. They predict that prospects for girls in the marriage market may become so auspicious that bearing female children may be seen as a positive rather than a negative.[46]

Excess men

Since the advent of sex-selective abortions via ultrasound and other medical procedures in the 1980s, the gender discriminations that have caused the “missing women” have simultaneously produced cohorts of excess men. Many speculated that this group of excess men would cause social disturbances such as crime and abnormal sexual behaviors without the opportunity to marry. In a 2011 study, Hesketh found crime rates to not differ significantly from areas with known higher populations of excess men. She found that instead of being prone to aggression these men are more likely to feel outcast and suffer from feelings of failure, loneliness and associated psychological problems.[47] Others are using emigration to other countries like the U.S or Russia as a solution.[47]

To combat runaway sex-ratio disparity, Hesketh recommends government policy to intervene by making sex selective abortion illegal and promoting awareness to fight son preference paradigms.[47]

Other impacts

A different development occurred in South Korea which in the early 1990s had one of the highest male to female ratios in the world. By 2007 however, South Korea, had a male to female ratio comparable to that found in Western Europe, the US and sub-Saharan Africa.

This development characterized both adult ratios as well as the ratios among new births. According to Chung and Das Gupta rapid economic growth and development in South Korea has led to a sweeping change in social attitudes and reduced the preference for sons.[48] Das Gupta, Chung, and Shuzhuo conclude that it is possible that China and India will experience a similar reversal in trend towards normal sex ratio in the near future if their rapid economic development, combined with policies that seek to promote gender equality, continue.[49] This reversal has been interpreted as the latest phase of a more complex cycle called the "sex ratio transition".[50]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Sen, Amartya (20 December 1990). "More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing". New York Review of Books 37 (20).

- ↑ https://www.aeaweb.org/articles.php?doi=10.1257/app.1.2.1

- ↑ http://www.economist.com/news/europe/21586617-son-preference-once-suppressed-reviving-alarmingly-gendercide-caucasus

- 1 2 Oster, Emily; Chen, Gang; Yu, Xinsen; Lin, Wenyao (2008). "Hepatitis B Does Not Explain Male-Biased Sex Ratios in China" (PDF). Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- ↑ Waldron, Ingrid (1983). "Sex differences in human mortality: The role of genetic factors". Social Science & Medicine 17 (6): 321–333. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(83)90234-4. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sen, Amartya. "MANY FACES OF GENDER INEQUALITY". Frontline. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

- ↑ Sen, Amartya (1990-12-20). "More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing". The New York Review of Books. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved 2015-09-15.

- 1 2 3 4 Sen, Amartya (1987). "Gender and cooperative conflicts.". Helsinki: World Institute for Development Economics Research.

- 1 2 Sen, Amartya (1992). "Missing Women" (PDF). BMJ: British Medical Journal. 304.6827 (6827): 587–8. PMC 1881324. PMID 1559085.

- ↑ Berik, Günseli; Cihan Bilginsoy (2000). "Type of work matters: women's labor force participation and the child sex ratio in Turkey." (PDF). World Development. 5 28: 861–878. doi:10.1016/s0305-750x(99)00164-3.

- 1 2 3 "The Daughter Deficit" by Tina Rosenberg, The New York Times Magazine, August 23, 2009.

- 1 2 Oster, Emily (2005). "Hepatitis B and the Case of the Missing Women" (PDF). Journal of Political Economy 113 (6): 1163–1216. doi:10.1086/498588. Retrieved 2007-08-01.

- ↑ Ebenstein, Avraham Y. (February 2007). "Fertility Choices and Sex Selection in Asia: Analysis and Policy" (PDF). Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- ↑ Oster, Emily (September 2005). "Explaining Asia's "Missing Women": A New Look at the Data – Comment" (PDF). Population and Development Review 31 (3): 529, 535. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00082.x. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- ↑ Lin, Ming-Jen; Luoh, Ming-Ching (2008). "Can Hepatitis B Mothers Account for the Number of Missing Women? Evidence from Three Million Newborns in Taiwan". American Economic Review 98 (5): 2259–73. doi:10.1257/aer.98.5.2259.

- ↑ Levitt, Steven (22 May 2008). "An Academic Does the Right Thing". Freakonomics: The Hidden Side of Everything. New York Times blogs.

- 1 2 3 4 Anderson, Siwan; Debraj Ray (2010). "Missing women: age and disease.". The Review of Economic Studies. 4 77 (4): 1262–1300. doi:10.1111/j.1467-937x.2010.00609.x.

- 1 2 Stillwaggon, Eileen (2008). "Race, sex, and the neglected risks for women and girls in sub-Saharan Africa.". Feminist Economics. 4 14: 67–86. doi:10.1080/13545700802262923.

- 1 2 James W.H. (July 2008). "Hypothesis:Evidence that Mammalian Sex Ratios at birth are partially controlled by parental hormonal levels around the time of conception" (PDF). Journal of Endocrinology 198 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1677/JOE-07-0446. PMID 18577567.

- ↑ see:

- James WH (1987). "The human sex ratio. Part 1: A review of the literature". Human Biology 59 (5): 721–752. PMID 3319883. Retrieved August 2011.

- James WH (1987). "The human sex ratio. Part 2: A hypothesis and a program of research". Human Biology 59 (6): 873–900. PMID 3327803. Retrieved August 2011.

- MARIANNE E. BERNSTEIN (1958). "Studies in The Human Sex Ratio 5. A Genetic Explanation of the Wartime Secondary Sex Ratio" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics 10 (1): 68–70. PMC 1931860. PMID 13520702.

- France MESLÉ, Jacques VALLIN, Irina BADURASHVILI (2007). A Sharp Increase in Sex Ratio at Birth in the Caucasus. Why? How? (PDF). Committee for International Cooperation in National Research in Demography. pp. 73–89. ISBN 2-910053-29-6.

- ↑ JAN GRAFFELMAN and ROLF F. HOEKSTRA, A Statistical Analysis of the Effect of Warfare on the Human Secondary Sex Ratio, Human Biology, Vol. 72, No. 3 (June 2000), pp. 433-445

- ↑ R. Jacobsen, H. Møller and A. Mouritsen, Natural variation in the human sex ratio, Hum. Reprod. (1999) 14 (12), pp 3120-3125

- ↑ T Vartiainen, L Kartovaara, and J Tuomisto (1999). "Environmental chemicals and changes in sex ratio: analysis over 250 years in finland". Environmental Health Perspectives 107 (10): 813–815. doi:10.1289/ehp.99107813. PMC 1566625. PMID 10504147.

- ↑ Michel Garenne, Southern African Journal of Demography, Vol. 9, No. 1 (June 2004), pp. 91-96

- ↑ Michel Garenne, Southern African Journal of Demography, Vol. 9, No. 1 (June 2004), page 95

- ↑ RB Campbell, John Graunt, John Arbuthnott, and the human sex ratio, Hum Biol. 2001 Aug;73(4):605-610

- ↑ Ciocco, A. (1938), Variations in the ratio at birth in USA, Human Biology, 10:36–64

- ↑ Sen, Amartya (1990). "More than 100 million women are missing.". The New York Review of Books 37.

- ↑ Coale, Ansley (1991). "Excess Female Mortality and the Balance of the Sexes in the Population: An Estimate of the Number of "Missing Females". Population and Development review. 3 17: 517–523. doi:10.2307/1971953.

- ↑ Klasen, Stephan; Claudia Wink (2002). "A turning point in gender bias in mortality? An update on the number of missing women". Population and Development Review. 2 28: 285–312. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2002.00285.x.

- ↑ Anderson, Siwan; Debraj Ray (2010). "Missing women: age and disease.". The Review of Economic Studies. 4 77 (4): 1262–1300. doi:10.1111/j.1467-937x.2010.00609.x.

- ↑ Bulte, Erwin; Nico Heenrink; Xiaobo Zhang (2011). "China's One‐Child Policy and ‘the Mystery of Missing Women': Ethnic Minorities and Male‐Biased Sex Ratios*.". Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. 1 73: 21–39. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0084.2010.00601.x.

- ↑ Merli, Giovanna; Adrian E. Raftery (2000). "Are births underreported in rural China? Manipulation of statistical records in response to China's population policies.". Demography. 1 37 (1): 109–126. doi:10.2307/2648100. PMID 10748993.

- ↑ Goodkind, Daniel (2011). "Child underreporting, fertility, and sex ratio imbalance in China.". Demography. 1 48: 291–316. doi:10.1007/s13524-010-0007-y.

- 1 2 Pearson, Veronica (2006). "A Broken Compact." China's Deep Reform: Domestic Politics in Transition. p. 431.

- ↑ Meier, Patricia J.; Xiaole Zhang (2008). "Sold into adoption: the Hunan baby trafficking scandal exposes vulnerabilities in Chinese adoptions to the United States" (PDF). Cumberland Law Review 39 (87).

- 1 2 Goodman, Peter S. (Mar 12, 2006). "Stealing Babies for Adoption: With U.S. Couples Eager to Adopt, Some Infants Are Abducted and Sold in China". Washington Post. Retrieved 4/11/14. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ VALERIE M. HUDSON and ANDREA M. DEN BOER Missing Women and Bare Branches: Gender Balance and Conflict ECSP Report, Issue 11

- ↑ Klausen, Stephan; Wink, Claudia (2003). "Missing Women: Revisiting the Debate". Feminist Economics 9: 263–299. doi:10.1080/1354570022000077999.

- ↑ Klausen, Stephan; Wink, Claudia (2003). "Missing Women: Revisiting the Debate". Feminist Economics 9: 270. doi:10.1080/1354570022000077999.

- 1 2 3 Christophe Z Guilmoto, Sex imbalances at birth Trends, consequences and policy implications United Nations Population Fund, Hanoi (October 2011)

- ↑ Dyson, Tim (2001). "The Preliminary Demography of the 2001 Census of India". Population and Development Review 27 (2): 341–356. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2001.00341.x.

- ↑ Klasen, Stephan; Wink, Claudia (2002). "A Turning Point in Gender Bias in Mortality? an update on the number of missing women". Population and Development Review 28 (2): 285–312. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2002.00285.x.

- ↑ Nussbaum, Martha (1999). "Women and equality: the capabilities approach.". International Labour Review. 3 138: 227–245. doi:10.1111/j.1564-913X.1999.tb00386.x.

- ↑ d'Albis, Hippolyte; David De La Croix (2012). "Missing daughters, missing brides?.". Economics Letters. 3 116: 358–360. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2012.03.032.

- ↑ Kaur, Ravinder (2008). "Missing women and brides from faraway: Social consequences of the skewed sex ratio in India.". AAS (Austrian Academy of Sciences) Working Papers in Social Anthropology, Approbated: 1–13.

- 1 2 3 Hesketh, Therese (2011). "Selecting sex: The effect of preferring sons.". Early human development 87 (11): 759–761. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.08.016.

- ↑ Chung, Woojin; Das Gupta, Monica (2007). "The Decline of Son Preference in South Korea: the roles of development and public policy". Population and Development Review 33 (4): 757–783. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2007.00196.x.

- ↑ Das Gupta, Monica; Chung, Woojin; Shuzhuo, Li (February 2009). "Is There an Incipient Turnaround in Asia's 'Missing Girls' Phenomenon?". World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4846. doi:10.1596/1813-9450-4846. SSRN 1354952.

- ↑ Guilmoto, Christophe Z. (2009). "The Sex Ratio Transition in Asia" (PDF). CEPED Working Paper 5. Retrieved 2009-11-19.