Missa prolationum

The Missa prolationum is a musical setting of the Ordinary of the Mass by Johannes Ockeghem, dating from the second half of the 15th century. Based on freely written material probably composed by Ockeghem himself, and consisting entirely of mensuration canons,[1] it has been called "perhaps the most extraordinary contrapuntal achievement of the fifteenth century",[2] and was possibly the first multi-part work written with a unifying canonic principle for all its movements.[3][4]

Music

The mass is for four voices, and is in the usual parts:

A typical performance takes 30 to 35 minutes.

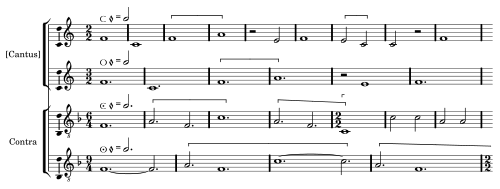

The mass uses progressive canon through all its movements, similar to the way Palestrina used the technique in his "Missa Repleatur os meum" (Third Book of Masses, 1570), and to J.S. Bach's use of canon in the canonic movements of the Goldberg Variations more than two centuries later. Most of the movements feature pairs of mensuration canons. The interval separating the two voices singing each canon grows successively in each consecutive movement, beginning on the unison, proceeding next to the second, then the third, and so forth, reaching the octave at the "Osanna" section in the Sanctus. The four voices each sing in a different mensuration. For instance, in the first "Kyrie", the four voices sing in the meters 2/2, 3/2, 6/4, and 9/4 respectively (in modern notation). Thus, the second voice, in 3/2, sings the same tune as the first voice, in 2/2, but half again as slowly, so the voices pull apart gradually. The same occurs between the second pair of voices, in 6/4 and 9/4 respectively. In the score, only one voice was written out for each canon, with the mensuration marks (approximately equivalent to a modern time signature) given alongside, so the singers would understand that they are to sing in those proportions, and thus at different speeds; in addition, the intervals between the voices are given in the score by the positions of the C clefs. What has so astonished musicians and listeners from Ockeghem's age to the present day is that he was able to accomplish this extraordinarily difficult feat.[5]

Ockeghem was the first composer to write canons using the intervals of the second, third, sixth, and seventh, the "imperfect" intervals, and the Missa prolationum may have been the first work to employ them. The layout of the work, with the interval of imitation expanding from the unison up to the octave, is the same as that used by J.S. Bach in the Goldberg Variations; it is not known, however, if Bach was familiar with Ockeghem's work (which was generally unavailable in the 18th century).[6] Another unusual feature of this mass is that the melodies used for its canons were all apparently freely composed; none have been identified from other sources. During this period of musical history, composers usually built masses on pre-existing tunes, such as Gregorian chant or even popular songs.

Source and dating

There are two sources preserving the mass. One is the Chigi Codex (f.106v to 114r), which was copied for Philip I of Castile sometime between 1498 and 1503, shortly after Ockeghem's death. The other one is the Vienna manuscript (Wien, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Handschriftensammlung, MS 11883, f.208r to 221r). Exactly when he wrote the Missa prolationum is not known, and there is no evidence to allow its dating other than what can be inferred from its internal characteristics, or from a comparison with other works of Ockeghem which already have tentative dates (Ockeghem's output is notoriously resistant to precise dating, even for a composer of the Renaissance; not only did he have an unusually long career, possibly spanning sixty active years as a composer, but there are few records tying specific pieces to events). No dates more precise than "mid-15th century" or "second half of 15th century" have been established for this piece.[7]

References

- Leeman Perkins, "Johannes Ockeghem." The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie. London, Macmillan, 1980. (20 vol.) ISBN 1-56159-174-2.

- Leeman Perkins, "Johannes Ockeghem." Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed July 31, 2007), (subscription access)

- Alfred Mann, J. Kenneth Wilson, Peter Urquhart, "Canon." Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed July 31, 2007), (subscription access)

- Lewis Lockwood, Andrew Kirkman, "Mass." Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed July 31, 2007), (subscription access)

- Allan W. Atlas, Renaissance Music: Music in Western Europe, 1400–1600. New York, W.W. Norton & Co., 1998. ISBN 0-393-97169-4

Notes

- ↑ Johannes Ockeghem, "Masses and Mass Sections IX-XVI." Ed. D. Plamenac. Publikationen älterer Musik, ii (New York, 1947, 2/1966).

- ↑ Perkins, Grove (1980)

- ↑ Perkins, Grove (1980)

- ↑ Lockwood/Kirkman, "Mass", Grove online

- ↑ Atlas, p. 153-4

- ↑ Mann/Wilson/Urquhart, Canon, Grove online

- ↑ Mann/Wilson/Urquhart, Canon, Grove online

| ||||||||||