Military recruitment

Military recruitment is recruitment for military positions, that is, the act of requesting people, usually male adults, to join a military voluntarily. Involuntary military recruitment is known as conscription. Even before the era of all-volunteer militaries, recruitment of volunteers was an important component of filling military positions, and in countries that have abolished conscription, it is the sole means. To facilitate this process, armed forces have established recruiting commands.

Military recruitment can be considered part of military science if analysed as part of military history. Acquiring large amounts of forces in a relatively short period of time, especially voluntarily, as opposed to stable development, is a frequent phenomenon in history. One particular example is the regeneration of the military strength of the Communist Party of China from a depleted force of 8,000 following the Long March in 1934 into 2.8 million near the end of the Chinese Civil War 14 years later.

Recent cross-cultural studies suggest that, throughout the world, the same broad categories may be used to define recruitment appeals. They include war, economic motivation, education, family and friends, politics, and identity and psychosocial factors.[1]

Wartime recruitment strategies in the US

Prior to the outbreak of World War I, military recruitment in the US was conducted primarily by individual states.[2] Upon entering the war, however, the federal government took on an increased role.

The increased emphasis on a national effort was reflected in World War I recruitment methods. Peter A. Padilla and Mary Riege Laner define six basic appeals to these recruitment campaigns: patriotism, job/career/education, adventure/challenge, social status, travel, and miscellaneous. Between 1915 and 1918, 42% of all army recruitment posters were themed primarily by patriotism.[2] And though other themes - such as adventure and greater social status - would play an increased role during World War II recruitment, appeals to serve one’s country remained the dominant selling point.

Recruitment without conscription

In the aftermath of World War II military recruitment shifted significantly. With no war calling men and women to duty, the United States refocused its recruitment efforts to present the military as a career option, and as a means of achieving a higher education. A majority - 55% - of all recruitment posters would serve this end. And though peacetime would not last, factors such as the move to an all-volunteer military would ultimately keep career-oriented recruitment efforts in place.[3] The Defense Department turned to television syndication as a recruiting aid from 1957-1960 with a filmed show, Country Style, USA.

On February 20, 1970, the President’s Commission on an All-Volunteer Armed Force unanimously agreed that the United States would be best served by an all-volunteer military. In supporting this recommendation, the committee noted that recruitment efforts would have to be intensified, as new enlistees would need to be convinced rather than conscripted. Much like the post-World War II era, these new campaigns put a stronger emphasis on job opportunity. As such, the committee recommended “improved basic compensation and conditions of service, proficiency pay, and accelerated promotions for the highly skilled to make military career opportunities more attractive.” These new directives were to be combined with “an intensive recruiting effort.” [4] Finalized in mid-1973, the recruitment of a “professional” military was met with success. In 1975 and 1976, military enlistments exceeded expectations, with over 365,000 men and women entering the military. Though this may, in part, have been the result of a lack of civilian jobs during the recession, it nevertheless stands to underline the ways in which recruiting efforts responded to the circumstances of the time.[5]

Indeed, recommendations made by the President's Commission continue to work in present-day recruitment efforts. Understanding the need for greater individual incentive, the US military has re-packaged the benefits of the GI Bill. Though originally intended as compensation for service, the bill is now seen as a recruiting tool. Today, the GI Bill is "no longer a reward for service rendered, but an inducement to serve and has become a significant part of recruiter's pitches.” [6]

Recruiting Methods

Recruitment can be conducted over the telephone with organized lists, through email campaigns and from face to face prospecting. While telephone prospecting is the most efficient, face to face prospecting is the most effective. Military recruiters often set up booths at amusement parks, sports stadiums and other attractions. In recent years social media has been more commonly used.

Controversy

Military recruitment in the United Kingdom

During both world wars and a period after the second, military service was mandatory for at least some of the British population. At other times, techniques similar to those outlined above have been used. The most prominent concern over the years has been the minimum age for recruitment, which has been 16 for many years.[7] This has now been raised to 18 in relation to combat operations. In recent years, there have been various concerns over the techniques used in (especially) army recruitment in relation to the portrayal of such a career as an enjoyable adventure.[8][9]

Military recruitment in the United States

The American military has had recruiters since the time of the colonies in the 1700s. Today there are thousands of recruiting station across the United States, serving the Army, Navy, Marines, and Air Force. Recruiting offices normally consist of 2-8 recruiters between the ranks of E-5 and E-7. When a potential applicant walks into a recruiting station his or her height and weight are checked and their background investigated. A finger print scan is conducted and a practice ASVAB exam is given to them. Applicants can not officially swear their enlistment oath in the recruiting office. This is conducted at a Military Entrance Processing Station - MEPS.

Military recruitment in India

From the times of the British Raj, recruitment in India has been voluntary. Using Martial Race theory, the British recruited heavily from selected communities for service in the colonial army.[10] The largest of the colonial military forces the British Indian Army of the British Raj until Military of India, was a volunteer army, raised from the native population with British officers. The Indian Army served both as a security force in India itself and, particularly during the World Wars, in other theaters. About 1.3 million men served in the First World War. During World War II, the British Indian Army would become the largest volunteer army in history, rising to over 2.5 million men in August 1945.[11]

Recruitment centres

A recruitment centre in the UK, recruiting station in the U.S., or recruiting office in New Zealand,[12] is a building used to recruit people into an organization, and is the most popularized method of military recruitment. The U.S. Army refers to their offices as recruiting centers as of 2012.

-

A British Military recruitment centre in Oxford

-

A United States Military recruiting station on Times Square, NYC

-

A New Zealand Defence Force recruiting office in Palmerston North, New Zealand

Recruitment posters

A recruitment poster is a poster used in advertisement to recruit people into an organization, and was a popularized method of military recruitment.

-

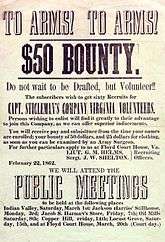

"To Arms! To Arms!" Recruitment poster for Confederate States of America. Floyd County, Virginia, 1862.

-

_Britons_(Kitchener)_wants_you_(Briten_Kitchener_braucht_Euch)._1914_(Nachdruck)%2C_74_x_50_cm._(Slg.Nr._552).jpg)

A World War I recruitment poster featuring Lord Kitchener (British Minister of War)

-

J. M. Flagg's Uncle Sam recruited soldiers for World War I, and was revived in later wars. Based on the Kitchener poster

-

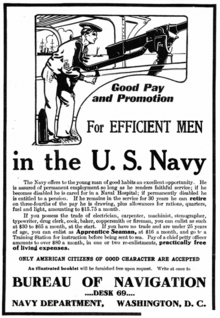

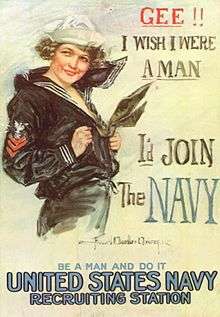

Recruiting poster made by and for the United States Navy c.1917

-

A Canadian World War I recruitment poster

-

An Australian World War I recruitment poster

-

Recruitment poster for Polish Army in France

-

"Why aren't you in the army?" Volunteer Army recruitment poster during the Russian Civil War featuring Anton Denikin.

See also

- America's Army (game)

- Be All You Can Be

- Canada First Defence Strategy

- Counter-recruitment

- Impressment

- Rumsfeld v. Forum for Academic and Institutional Rights

- Solomon Amendment

References

- ↑ Brett, Rachel, and Irma Specht. Young Soldiers: Why They Choose to Fight. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2004. ISBN 1-58826-261-8

- 1 2 Padilla, Peter A. and Mary Riege Laner. “Trends in Military Influences on Army Recruitment: 1915-1953.” Sociological Inquiry, Vol. 71, No. 4. Fall 2001421-36. Austin: University of Texas Press. Page 423

- ↑ Padilla, Peter A. and Mary Riege Laner. “Trends in Military Influences on Army Recruitment: 1915-1953.” Sociological Inquiry, Vol. 71, No. 4. Fall 2001421-36. Austin: University of Texas Press. Page 433

- ↑ The Report of the President’s Commission on an All-Volunteer Armed Force. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1970. Page 18.

- ↑ Bliven, Bruce Jr. Volunteers, One and All. New York: Readers Digest Press, 1976. ISBN 0-88349-058-7

- ↑ White, John B. Lieutenant Commander, US Naval Reserve, Ph. D. "The GI Bill: Recruiting Bonus, Retention Onus." Military Review, July–August 2004.

- ↑ "Marching orders for teenage soldiers?". BBC News. June 22, 1998. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ↑ "MoD denies 'war glamour' claim". BBC News. January 7, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Teachers reject 'Army propaganda'". BBC News. March 25, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ↑ http://www.expressindia.com/latest-news/compulsory-military-service-could-be-an-option-in-future/416902/

- ↑ "Commonwealth War Graves Commission Report on India 2007–2008" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-09-07.

- ↑

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to World War I recruitment posters. |

Further reading

Manigart, Philippe. “Risks and Recruitment in Postmodern Armed Forces: The Case of Belgium.” Armed Forces & Society, Jul 2005; vol. 31: pp. 559–582.

Dandeker, Christopher and Alan Strachan. “Soldier Recruitment to the British Army: a Spatial and Social Methodology for Analysis and Monitoring.” Armed Forces & Society, Jan 1993; vol. 19: pp. 279–290.

Snyder, William P. “Officer Recruitment for the All-Volunteer Force: Trends and Prospects.” Armed Forces & Society, Apr 1984; vol. 10: pp. 401–425.

Griffith, James. “Institutional Motives for Serving in the U.S. Army National Guard: Implications for Recruitment, Retention, and Readiness.” Armed Forces & Society, Jan 2008; vol. 34: pp. 230–258.

Fitzgerald, John A. “Changing Patters of Officer Recruitment at the U.S. Naval Academy.” Armed Forces & Society, Oct 1981; vol. 8: pp. 111–128.

Eighmey, John. “Why Do Youth Enlist?: Identification of Underlying Themes.” Armed Forces & Society, Jan 2006; vol. 32: pp. 307–328.