Military of ancient Egypt

| Armed Forces of the Arab Republic of Egypt |

|---|

.svg.png) |

| Service branches |

| Other branches |

|

| Armies and Military Areas |

| Special Forces |

| Ranks of the Egyptian Military |

| History of the Egyptian military |

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of eastern North Africa, concentrated along the Northern reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. The civilization coalesced around 3150 BC[1] with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh, and it developed over the next three millennia.[2] Its history occurred in a series of stable Kingdoms, separated by periods of relative instability known as Intermediate Periods. Ancient Egypt reached its pinnacle during the New Kingdom, after which it entered a period of slow decline. Egypt was conquered by a succession of foreign powers in this late period, and the rule of the pharaohs officially ended in 31 BC when the early Roman Empire conquered Egypt and made it a province.[3] Although the Egyptian military forces in the Old and Middle kingdoms were well maintained, the new form that emerged in the New Kingdom showed the state becoming more organized to serve its needs.[4]

For most parts of its long history, ancient Egypt was unified under one government. The main military concern for the nation was to keep enemies out. The arid plains they wanted to get rid of and deserts surrounding Egypt were inhabited by nomadic tribes who occasionally tried to raid or settle in the fertile Nile river valley. Nevertheless the great expanses of the desert formed a barrier that protected the river valley and was almost impossible for massive armies to cross. The Egyptians built fortresses and outposts along the borders east and west of the Nile Delta, in the Eastern Desert, and in Nubia to the south. Small garrisons could prevent minor incursions, but if a large force was detected a message was sent for the main army corps. Most Egyptian cities lacked city walls and other defenses.

The history of ancient Egypt is divided into three kingdoms and two intermediate periods. During the three Kingdoms Egypt was unified under one government. During the Intermediate periods (the periods of time between Kingdoms) government control was in the hands of the various nomes (provinces within Egypt) and various foreigners. The geography of Egypt served to isolate the country and allowed it to thrive. This circumstance set the stage for many of Egypt's military conquests. They enfeebled their enemies by using small projectile weapons, like bows and arrows. They also had chariots which they used to charge at the enemy.

The Old Kingdom

The Old Kingdom was one of the most prosperous times in Egypt's history. Because of this affluence, it allowed the government to stabilize and in turn organize a functioning military. Before Egypt's New Kingdom, there were four major causes for military conflict.

- The Libyans from the Sahara to the west

- The Nubians from the south

- The Sinai and Canaanites to the north

- Internal conflict when the regions, or nomes, divided from the monarchy to form rival factions

All of the areas outside Egypt were connected in conflict either by raiding parties entering Egypt or Egypt maintaining a policy of eradication imperialism. The Old Kingdom's military was most marked by their construction of forts along the Nile River. At this time, the main conflict was with Nubia (to the south) and Egypt felt the urge to defend their borders by building forts deep into this country. These forts were never actually attacked, but they acted as a deterring factor towards potential invaders. Many are currently underwater in Lake Nasser, but while they were visible they were a true testament to the affluence and military prowess of ancient Egypt during this time. During the Old Kingdom there was no professional army in Egypt. Governors of each Nome (administrative division) had to raise their own volunteer army.[5] Then, all the armies would come together under the Pharaoh to battle. Because the army was not a very prestigious position, it was mostly made up of lower-class men, who could not afford to train in other jobs[6]

Old Kingdom soldiers were equipped with many types of weapons, including shields, spears, cudgels, maces, daggers, and bows and arrows. The most common Egyptian weapon was the bow and arrow. During the Old Kingdom, a single-arched bow was often used. This type of bow was difficult to draw, and there was less draw length. After the composite bow was introduced by the Hyksos, Egyptian soldiers used this weapon as well.[7]

The Middle Kingdom

In the Middle Kingdom, the theory of equilibrium imperialism really began to develop. Egypt's control of the surrounding territories became something that the military was forced to be directly involved in. They needed to control their own borders for several reasons. First of all, Egypt was protecting her own strength, land, and resources. Also, she needed to control trade routes so Egypt could continue to be wealthy and powerful. Borders were also expanded during this time.

The Second Intermediate Period

After Menferre Ay fled his palace in at the end of the 13th dynasty, a Canaanite tribe called the Hyksos sacked Memphis (the Egyptians' capital city) and claimed dominion over Upper and Lower Egypt. After the Hyksos took control, many Egyptians fled to Thebes, where they eventually began to oppose the Hyksos rule.[8]

The Hyksos, Asiatics from the Northeast, set up a fortified capital at Avaris. The Egyptians were trapped at this time; their government had collapsed. They were literally in the middle of an 'enemy sandwich' between the Hyksos in the north and the Kushite Nubians in the south. This period marked a great change for Egypt's military. The Hyksos brought with them to Egypt the horse, the chariot, and the composite bow. These tools drastically altered the way Egypt's military functioned. The Hyksos introduced the Ourarit (Chariot) to the Egyptians. Although the Hyksos have been credited with these introductions, a fragment from a Stela shows Khonsuemwaset, son of Pharaoh Dudimose, one of the last rulers of the 13th Dynasty, with a pair of chariot gloves under his seat, which denote his status as Master of the Horse, as is seen in the tomb of Ay (18th Dynasty), with him depicted as Master of the Horse, wearing charioteer's gloves, like those depicted in the above stela fragment.[9] Clearer evidence for the use of horses in the early SIP comes from Tell-el-Khebir, where Ali Hassan had excavated the complete skeleton of a horse, which he has dated, from associated finds, to the 13th Dynasty.[10] Kanawati has also uncovered a 12th Dynasty tomb at el-Rakakna containing an object engraved with the head of a horse'.[11] The Chariot was not invented by the Hyksos but was introduced in the north by the Hurrians.[6] The composite bow allowed for more accuracy and kill distance with arrows. These advances ultimately worked against the Hyksos because they allowed the Egyptian military to mobilize and oust them from Egypt, beginning when Seqenenre Tao became ruler of Thebes and opened a struggle that claimed his own life in battle. Seqenenre was succeeded by Kamose, who continued to battle the Hyksos, before his brother Ahmose was finally successful in driving them from Egypt.[8] This marked the beginning of the New Kingdom.

The New Kingdom

In the New Kingdom new threats emerged. However, the military contributions of the Hyksos allowed Egypt to defend themselves from these foreign invasions successfully. The Hittites hailed from further northeast than had been previously encountered. They attempted to conquer Egypt, yet were defeated and a peace treaty was made. Also, the mysterious Sea Peoples invaded the entire ancient Near East during this time. The Sea Peoples caused many problems, but ultimately the military was strong enough at this time to prevent a collapse of the government. The Egyptians were strongly vested in their infantry, unlike the Hittites who were dependent on their chariots. It is in this way the New Kingdom army was different than its two preceding kingdoms.[12]

Old & Middle Kingdom Armies

Before the New Kingdom the Egyptian armies were composed of conscripted peasants and artisans, who would then mass under the banner of the pharaoh.[5] During the Old and Middle Kingdom Egyptian armies were very basic. The Egyptian soldiers carried a simple armament consisting of a spear with a copper spearhead and a large wooden shield covered by leather hides. A stone mace was also carried in the Archaic period, though later this weapon was probably only in ceremonial use, and was replaced with the bronze battle axe. The spearmen were supported by archers carrying a simple curved bow and arrows with arrowheads made of flint or copper. No armor was used during the 3rd and early 2nd Millennium BC. Foreigners were also incorporated into the army, Nubians (Medjay), entered Egyptian armies as mercenaries and formed the best archery units.[7]

New Kingdom Armies

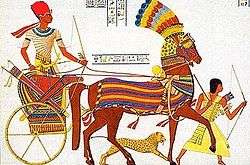

The major advance in weapons technology and warfare began around 1600 BC when the Egyptians fought and finally defeated the Hyksos people who had made themselves lords of Lower Egypt.[5] It was during this period the horse and chariot were introduced into Egypt, which the Egyptians had no answer to until they introduced their own version of the war chariot at the beginning of the 18th Dynasty.[5] The Egyptians then improved the design of the chariot to suit their own requirements. That made the Egyptian chariots lighter and faster than those of other major powers in the Middle East. Egyptian war chariots were manned by a driver holding a whip and the reigns and a fighter, generally wielding a composite bow or, after spending all his arrows, a short spear of which he had a few.[7] The charioteers wore occasionally scale armour, but many preferred broad leather bands crossed over the chest or carried a shield. Their torso was thus more or less protected, while the lower body was shielded by the chariot itself. The pharaohs often wore scale armour with inlaid semi-precious stones, which offered better protection, the stones being harder than the metal used for arrow tips.[13] The principal weapon of the Egyptian army was the bow and arrow; it was transformed into a formidable weapon with the introduction by the Hyksos of the composite bow. These bows, combined with the war chariot, enabled the Egyptian army to attack quickly and from a distance.[14] Other new technologies included the khopesh,[14] which temple scenes show being presented to the king by the gods with a promise of victory, body armour, in the 19th Dynasty soldiers began wearing leather or cloth tunics with metal scale coverings,[15] and improved bronze casting. Their presence also caused changes in the role of the military in Egyptian society and so during the New Kingdom, the Egyptian military changed from levy troops into a firm organization of professional soldiers.[5][16] Conquests of foreign territories, like Nubia, required a permanent force to be garrisoned abroad. The encounter with other powerful Near Eastern kingdoms like Mitanni, the Hittites, and later the Assyrians and Babylonians, made it necessary for the Egyptians to conduct campaigns far from home. Over 4,000 infantry of an army corps were organized into 20 companies between 200 and 250 men each.[17] There were also Companies of Libyans, Nubians, Canaanite and Sherdens who served in the Egyptian army. They were often described as mercenaries but they were most likely impressed prisoners who preferred the life of a soldier instead of slavery.[18]

Late Period Armies

The next leap forwards came in the Later Period (712-332 BC), when mounted troops and weapons made of iron came into use. After the conquest by Alexander the Great, Egypt was heavily hellenised and the main military force became the infantry phalanx. The ancient Egyptians were not great innovators in weapons technology, and most weapons technology innovation came from Eastern Asia and the Greek world.

Military Organization

As early as the Old Kingdom (c.2686-2160 BC) Egypt used specific military units, with military hierarchy appearing in the Middle Kingdom (c.2055-1650 BC). By the New Kingdom (c.1550-1069 BC), the Egyptian military consisted of three major branches: the infantry, the chariotry, and the navy.[19]

Infantry

Infantry troops were partially conscripted, partially voluntary.[20] Egyptian soldiers worked for pay, both natives and mercenaries.[21] Of mercenary troops, Nubians were used beginning in the late Old Kingdom, Asiatic maryannu troops were used in the Middle and New Kingdoms, and the Sherden, Libyans, and the "Na'arn" were used in the Ramesside Period [22] (New Kingdom, Dynasties XIX and XX, c.1292-1075 BC[23]).

Chariotry

Chariotry, the backbone of the Egyptian army, was introduced into ancient Egypt from Western Asia at the end of the Second Intermediate Period (c.1650-1550 BC) / the beginning of the New Kingdom (c.1550-1069 BC).[24] Charioteers were drawn from the upper classes in Egypt. Chariots were generally used as a mobile platform from which to use projectile weapons, and were generally pulled by two horses[25] and manned by two charioteers; a driver who carried a shield, and a man with a bow or javelin. Chariots also had infantry support.[26] By the time of Qadesh, the chariot arm was at the height of its development. It was designed for speed and maeuverability, being lightweight and delicate in appearance. Its offensive power was in its capacity to rapidly turn, wheel and repeatedly charge, penetrating the enemy line and functioning as a mobile firing platform that afforded the fighting crewmen the opportunity to shoot many arrows from the composite bow. The chariot corps served as an independent arm but were attached to the infantry corps. At Qadesh, there were 25 vehicles per company. Many of the lighter vehicles were retained for scouting and communication duties. In combat, the chariots were deployed in troops of 10, squadrons of 50 and the larger unit was called the pedjet, commanded by an officer with the title 'Commander of a chariotry host' and numbering about 250 chariots.[27]

Navy

Before the New Kingdom, the Egyptian military was mainly aquatic, and the high ranks were composed of the elite middle class Egyptians.[28] Egyptian troops were transported by naval vessels as early as the Late Old Kingdom.[29] By the later intermediate period, the navy was highly sophisticated, and used complicated naval maneuvers, e.g. Kamose's campaign against the Hyksos in the harbor of Avaris (c.1555-1550 BC)[30]

Projectile Weapons

Projectile weapons were used by the ancient Egyptians as standoff artillery, used to weaken the enemy before an infantry assault. Slings, throw sticks, spears, and javelins were used, but the bow and arrow was the primary projectile weapon for most of Egypt's history.

The Throw Stick

The throw stick does appear to have been used to some extent during Egypt's predynastic period as a weapon, but it seems to have not been very effective for this purpose. Because of their simplicity, skilled infantry continued to use this weapon at least with some regularity through the end of the New Kingdom. It was used extensively for hunting fowl through much of Egypt's dynastic period. Most of the Egyptians were intent on using this weapon for it had a holy effect as well.

The Spear

The spear does not fit comfortably into either the close combat class or the projectile type of weapons. It could be either. During the Old and Middle Kingdom of Egypt's Dynastic period, it typically consisted of a pointed blade made of copper or flint that was attached to a long wooden shaft by a tang. Conventional spears were made for throwing or thrusting, but there was also a form of spear (halberd) which was fitted with an axe blade and thus used for cutting and slashing.

The spear was used in Egypt since the earliest times for hunting larger animals, such as lions. In its form of javelin (throwing spears) it was replaced early on by the bow and arrow. Because of its greater weight, the spear was better at penetration than the arrow, but in a region where armor consisted mostly of shields, this was only a slight advantage. On the other hand, arrows were much easier to mass-produce.

In war it never gained the importance among Egyptians which it was to have in classical Greece, where phalanxes of spear-carrying citizens fought each other. During the New Kingdom, it was often an auxiliary weapon of the charioteers, who were thus not left unarmed after spending all their arrows. It was also most useful in their hands when they chased down fleeing enemies stabbing them in their backs. Amenhotep II's victory at Shemesh-Edom in Canaan is described at Karnak:

"...... Behold His Majesty was armed with his weapons, and His Majesty fought like Set in his hour. They gave way when His Majesty looked at one of them, and they fled. His majesty took all their goods himself, with his spear..... "

The spear was appreciated enough to be depicted in the hands of Ramesses III killing a Libyan. It remained short and javelin-like, just about the height of a man.[31]

Bow and arrow

The bow and arrow is one of ancient Egypt's most crucial weapons, used from Predynastic times through the Dynastic age and into the Christian and Islamic periods. The first bows were commonly "horn bows", made by joining a pair of antelope horns with a central piece of wood.

By the beginning of the Dynastic Period, bows were made of wood. They had a single curvature and were strung with animal sinews or strings made of plant fiber. In the pre-dynastic period, bows often had a double curvature, but during the Old Kingdom a single-arched bow, known as a self (or simple) bow, was adopted. These were used to fire reed arrows fletched with three feathers and tipped with flint or hardwood, and later, bronze. The bow itself was usually between one and two meters in length and made up of a wooden rod, narrowing at either end. Some of the longer self bows were strengthened at certain points by binding the wooden rod with cord. Drawing a single-arched bow was harder and one lost the advantage of draw-length double curvature provided.

During the New Kingdom the composite bow came into use, having been introduced by the Asiatic Hyksos. Often these bows were not made in Egypt itself but imported from the Middle East, like other 'modern' weapons. The older, single-curved bow was not completely abandoned, however. For example, it would appear that Tuthmosis III and Amenhotep II continued to use these earlier-styled bows. A difficult weapon to use successfully, it demanded strength, dexterity and years of practice. The experienced archer chose his weapon with care. For example, we are told that:

Amenhotep II ... drew three hundred of the bows hardest to bend in order to examine the workmanship, to distinguish between a worker who doesn't know his profession and the expert.

We are then told that he chose a bow without flaw which only he could draw.

... he came to the northern shooting range and found they had prepared for him four targets made of Asiatic copper thick as a man's palm. Twenty cubits divided between the poles. When His Majesty appeared in his Chariot like Montu with all his power, he reached for his bow and grabbed four arrows with one hand. He speeded his chariot shooting at the targets, like Montu the god. His arrow penetrated the target, cleaving it. He drew his bow again at the second target. None had ever hit a target like this, none had ever heard that a man shot an arrow a target made of copper and that it should cleave the target and fall to the ground, none but the king, strong and powerful, as Amen made him a conqueror.

The Composite Bow

The composite bow achieved the greatest possible range with a bow as small and light as possible. The maximum draw length was that of the archer's arm. The bow, while unstrung, curved outward and was under an initial tension, dramatically increasing the draw weight. A simple wooden bow was no match for the composite bow in range or power. The wood had to be supported, otherwise it would break. This was achieved by adding horn to the belly of the bow (the part facing the archer) which would be compressed during the draw. Sinew was added to the back of the bow, to withstand the tension. All these layers were glued together and covered with birch bark.

Composite bows needed more care than simple bows, and were much more difficult and expensive to produce. They were more vulnerable to moisture, requiring them to be covered. They had to be unstrung when not in use and re-strung for action, a feat which required not a little force and generally the help of a second person. As a result, they were not used as much as one might expect. The simple stave bow never disappeared from the battlefield, even in the New Kingdom. The simpler bows were used by the bulk of the archers, while the composite bows went first to the chariots, where their penetrative power was needed to pierce scale armor.

The first arrow-heads were flint, which was replaced by bronze in the 2nd millennium. Arrow-heads were mostly made for piercing, having a sharp point. However, the arrow heads could vary considerably, and some were even blunt (probably used more for hunting small game).

The Sling

Hurling stones with a sling demanded little equipment or practice in order to be effective. Secondary to the bow and arrow in battle, the sling was rarely depicted. The first drawings date to the 20th century BC. Made of perishable materials, few ancient slings have survived. It relied on the impact the missile made and like most impact weapons was relegated to play a subsidiary role. In the hands of lightly armed skirmishers it was used to distract the attention of the enemy. One of its main advantages was the easy availability of ammunition in many locations. When lead became more widely available during the Late Period, sling bullets were cast. These were preferred to pebbles because of their greater weight which made them more effective.[32] They often bore a mark.

Notes and references

- ↑ Only after 664 BC are dates secure. See Egyptian chronology for details. "Chronology". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- ↑ Dodson (2004) p. 46

- ↑ Clayton (1994) p. 217

- ↑ Healy, Mark (2005). Qadesh 1300 BC. London: Osprey. p. 27-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Egyptology Online

- 1 2 Benson, Douglas S. “Ancient Egypt’s Warfare: A survey of armed conflict in the chronology of ancient Egypt, 1600 BC-30 BC”, Bookmasters Inc., Ashland, Ohio, 1995

- 1 2 3 Ancient Egyptian Weapons

- 1 2 Tyldesley, Joyce A. “Egypt’s Golden Empire”, Headline Book Publishing, London, 2001. ISBN 0-7472-5160-6

- ↑ W. Helck"Ein indirekter Beleg fur die Benutzung des liechten Streitwagens in Agypten zu ende der 13 Dynastie", in JNES 37, pp. 337-40

- ↑ see Egyptian Archaeology 4, 1994

- ↑ see KMT 1:3 (1990), p. 5

- ↑ Healy, Mark (2005). Qadesh 1300 BC. London: Osprey. p. 35.

- ↑ Body armour

- 1 2 Pharaoh's Military

- ↑ Evolution of Warfare

- ↑ ncient Egyptian Army

- ↑ Healy, Mark (2005). Qadesh 1300 BC. London: Osprey. p. 37.

- ↑ Healy, Mark (2005). Qadesh 1300 BC. London: Osprey. p. 37-38.

- ↑ Darnell, John Colemen; Menassa, Colleen. TutanKhamun's Armies. John Wiley and Sons Inc., New Jersey: 2007. p.60

- ↑ Darnell, John Colemen; Menassa, Colleen. TutanKhamun's Armies. John Wiley and Sons Inc., New Jersey: 2007. pp.60-63

- ↑ Spangler, Anthony J.. War in Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA: 2005. p.7

- ↑ Spangler, Anthony J.. War in Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA: 2005. pp.6-7

- ↑ Hornung, Erik. History of Ancient Egypt. trans. Lorton, David. Cornell University Press, Ithica, New York: 1999. p.xvii

- ↑ Spangler, Anthony J.. War in Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA: 2005. p.8

- ↑ Spangler, Anthony J.. War in Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA: 2005. p.36

- ↑ Darnell, John Colemen; Menassa, Colleen. TutanKhamun's Armies. John Wiley and Sons Inc., New Jersey: 2007. pp.63-65

- ↑ Healy, Mark (2005). Qadesh 1300 BC. London: Osprey. p. 39.

- ↑ Spangler, Anthony J.. War in Ancient Egypt. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA: 2005. p.6

- ↑ Darnell, John Colemen; Menassa, Colleen. TutanKhamun's Armies. John Wiley and Sons Inc., New Jersey: 2007. p.65

- ↑ Darnell, John Colemen; Menassa, Colleen. TutanKhamun's Armies. John Wiley and Sons Inc., New Jersey: 2007. pp.65-66

- ↑ Edged Weapons: The Spear

- ↑ Projectiles

Further reading

- History of Ancient Egypt by Erik Hornung, 1999.

- War In Ancient Egypt by Anthony J. Spalinger, 2005.

- Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC by William J. Hamblin, 2006.

- The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign by Garry J. Shaw, 2012. See Chapter 5: Pharaohs on Campaign.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ancient Egyptian military equipment. |

- The Egypian Army In The Ancient Pharaonic History

- Ancient Egyptian and Roman armies

- The army in Ancient Egypt

- Egyptology Online

- Egyptian Warfare

- Projectile Type Weapons of Ancient Egypt

- The Military of Ancient Egypt

| ||||||||||||||||||||||