Microfinance

Microfinance is a source of financial services for entrepreneurs and small businesses lacking access to banking and related services. The two main mechanisms for the delivery of financial services to such clients are: (1) relationship-based banking for individual entrepreneurs and small businesses; and (2) group-based models, where several entrepreneurs come together to apply for loans and other services as a group. In some regions, for example Southern Africa, microfinance is used to describe the supply of financial services to low-income employees, which is closer to the retail finance model prevalent in mainstream banking.

For some, microfinance is a movement whose object is "a world in which as many poor and near-poor households as possible have permanent access to an appropriate range of high quality financial services, including not just credit but also savings, insurance, and fund transfers."[1] Many of those who promote microfinance generally believe that such access will help poor people out of poverty, including participants in the Microcredit Summit Campaign. For others, microfinance is a way to promote economic development, employment and growth through the support of micro-entrepreneurs and small businesses.

Microfinance is a broad category of services, which includes microcredit. Microcredit is provision of credit services to poor clients. Microcredit is one of the aspects of microfinance and the two are often confused. Critics may attack microcredit while referring to it indiscriminately as either 'microcredit' or 'microfinance'. Due to the broad range of microfinance services, it is difficult to assess impact, and very few studies have tried to assess its full impact.[2] Proponents often claim that microfinance lifts people out of poverty, but the evidence is mixed. What it does do, however, is to enhance financial inclusion.

Background

Microfinance and poverty

In developing economies and particularly in rural areas, many activities that would be classified in the developed world as financial are not monetized: that is, money is not used to carry them out. This is often the case when people need the services money can provide but do not have dispensable funds required for those services, forcing them to revert to other means of acquiring them. In their book The Poor and Their Money, Stuart Rutherford and Sukhwinder Arora cite several types of needs:

- Lifecycle Needs: such as weddings, funerals, childbirth, education, home building, widowhood and old age.

- Personal Emergencies: such as sickness, injury, unemployment, theft, harassment or death.

- Disasters: such as fires, floods, cyclones and man-made events like war or bulldozing of dwellings.

- Investment Opportunities: expanding a business, buying land or equipment, improving housing, securing a job (which often requires paying a large bribe), etc.[3]

People find creative and often collaborative ways to meet these needs, primarily through creating and exchanging different forms of non-cash value. Common substitutes for cash vary from country to country but typically include livestock, grains, jewelry and precious metals. As Marguerite Robinson describes in The Micro finance Revolution, the 1980s demonstrated that "micro finance could provide large-scale outreach profitably," and in the 1990s, "micro finance began to develop as an industry" (2001, p. 54). In the 2000s, the micro finance industry's objective is to satisfy the unmet demand on a much larger scale, and to play a role in reducing poverty. While much progress has been made in developing a viable, commercial micro finance sector in the last few decades, several issues remain that need to be addressed before the industry will be able to satisfy massive worldwide demand. The obstacles or challenges to building a sound commercial micro finance industry include:

- Inappropriate donor subsidies

- Poor regulation and supervision of deposit-taking micro finance institutions (MFIs)

- Few MFIs that meet the needs for savings, remittances or insurance

- Limited management capacity in MFIs

- Institutional inefficiencies

- Need for more dissemination and adoption of rural, agricultural micro finance methodologies

Microfinance is the proper tool to reduce income inequality, allowing citizens from lower socio-economical classes to participate in the economy. Moreover, its involvement has shown to lead to a downward trend in income inequality (Hermes, 2014).[4]

Ways In Which Poor People Manage Their Money

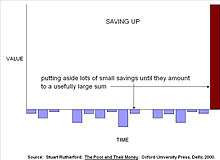

Rutherford argues that the basic problem that poor people face as money managers is to gather a 'usefully large' amount of money. Building a new home may involve saving and protecting diverse building materials for years until enough are available to proceed with construction. Children’s schooling may be funded by buying chickens and raising them for sale as needed for expenses, uniforms, bribes, etc. Because all the value is accumulated before it is needed, this money management strategy is referred to as 'saving up'.

Often, people don't have enough money when they face a need, so they borrow. A poor family might borrow from relatives to buy land, from a moneylender to buy rice, or from a microfinance institution to buy a sewing machine. Since these loans must be repaid by saving after the cost is incurred, Rutherford calls this 'saving down'. Rutherford's point is that microcredit is addressing only half the problem, and arguably the less important half: poor people borrow to help them save and accumulate assets. Microcredit institutions should fund their loans through savings accounts that help poor people manage their myriad risks.

Most needs are met through a mix of saving and credit. A benchmark impact assessment of Grameen Bank and two other large microfinance institutions in Bangladesh found that for every $1 they were lending to clients to finance rural non-farm micro-enterprise, about $2.50 came from other sources, mostly their clients' savings.[5] This parallels the experience in the West, in which family businesses are funded mostly from savings, especially during start-up.

Recent studies have also shown that informal methods of saving are unsafe. For example, a study by Wright and Mutesasira in Uganda concluded that "those with no option but to save in the informal sector are almost bound to lose some money—probably around one quarter of what they save there."[6]

The work of Rutherford, Wright and others has caused practitioners to reconsider a key aspect of the microcredit paradigm: that poor people get out of poverty by borrowing, building microenterprises and increasing their income. The new paradigm places more attention on the efforts of poor people to reduce their many vulnerabilities by keeping more of what they earn and building up their assets. While they need loans, they may find it as useful to borrow for consumption as for microenterprise. A safe, flexible place to save money and withdraw it when needed is also essential for managing household and family risk.

Examples

The microfinance project of "saving up" is exemplified in the slums of the south-eastern city of Vijayawada, India. This microfinance project functions as an unofficial banking system where Jyothi, a "deposit collector", collects money from slum dwellers, mostly women, in order for them to accumulate savings. Jyothi does her rounds throughout the city, collecting Rs5 a day from people in the slums for 220 days, however not always 220 days in a row since these women do not always have the funds available to put them into savings. They ultimately end up with Rs1000 at the end of the process. However, there are some issues with this microfinance saving program. One of the issues is that while saving, clients are actually losing part of their savings. Jyothi takes interest from each client—about 20 out of every 220 payments, or Rs100 out of 1,100 or 8%. When these slum dwellers find someone they trust, they are willing to pay up to 30% to someone to safely collect and keep their savings. There is also the risk of entrusting their savings to unlicensed, informal, peripatetic collectors. However, the slum dwellers are willing to accept this risk because they are unable to save at home, and unable to use the remote and unfriendly banks in their country. This microfinance project also has many benefits, such as empowering women and giving parents the ability to save money for their children’s education. This specific microfinance project is a great example of the benefits and limitations of the "saving up" project (Rutherford, 2009).

The microfinance project of "saving through" is shown in Nairobi, Kenya which includes a Rotating Savings and Credit Associations or ROSCAs initiative. This is a small scale example, however Rutherford (2009) describes a woman he met in Nairobi and studied her ROSCA. Everyday 15 women would save 100 shillings so there would be a lump sum of 1,500 shillings and everyday 1 of the 15 women would receive that lump sum. This would continue for 15 days and another woman within this group would receive the lump sum. At the end of the 15 days a new cycle would start. This ROSCA initiative is different from the "saving up" example above because there are no interest rates affiliated with the ROSCA, additionally everyone receives back what they put forth. This initiative requires trust and social capital networks in order to work, so often these ROSCAs include people who know each other and have reciprocity. The ROSCA allows for marginalized groups to receive a lump sum at one time in order to pay or save for specific needs they have.

Microfinance debates and challenges

There are several key debates at the boundaries of microfinance.

Interest rates

.jpg)

One of the principal challenges of microfinance is providing small loans at an affordable cost. The global average interest and fee rate is estimated at 37%, with rates reaching as high as 70% in some markets.[7] The reason for the high interest rates is not primarily cost of capital. Indeed, the local microfinance organizations that receive zero-interest loan capital from the online microlending platform Kiva charge average interest and fee rates of 35.21%.[8] Rather, the main reason for the high cost of microfinance loans is the high transaction cost of traditional microfinance operations relative to loan size.[9]

Microfinance practitioners have long argued that such high interest rates are simply unavoidable, because the cost of making each loan cannot be reduced below a certain level while still allowing the lender to cover costs such as offices and staff salaries. For example, in Sub-Saharan Africa credit risk for microfinance institutes is very high, because customers need years to improve their livelihood and face many challenges during this time. Financial institutes often do not even have a system to check the person's identity. Additionally they are unable to design new products and enlarge their business to reduce the risk.[10] The result is that the traditional approach to microfinance has made only limited progress in resolving the problem it purports to address: that the world's poorest people pay the world's highest cost for small business growth capital. The high costs of traditional microfinance loans limit their effectiveness as a poverty-fighting tool. Offering loans at interest and fee rates of 37% mean that borrowers who do not manage to earn at least a 37% rate of return may actually end up poorer as a result of accepting the loans.[11]

According to a recent survey of microfinance borrowers in Ghana published by the Center for Financial Inclusion, more than one-third of borrowers surveyed reported struggling to repay their loans. Some resorted to measures such as reducing their food intake or taking children out of school in order to repay microfinance debts that had not proven sufficiently profitable.

In recent years, the microfinance industry has shifted its focus from the objective of increasing the volume of lending capital available, to address the challenge of providing microfinance loans more affordably. Microfinance analyst David Roodman contends that, in mature markets, the average interest and fee rates charged by microfinance institutions tend to fall over time.[12] However, global average interest rates for microfinance loans are still well above 30%.

The answer to providing microfinance services at an affordable cost may lie in rethinking one of the fundamental assumptions underlying microfinance: that microfinance borrowers need extensive monitoring and interaction with loan officers in order to benefit from and repay their loans. The P2P microlending service Zidisha is based on this premise, facilitating direct interaction between individual lenders and borrowers via an internet community rather than physical offices. Zidisha has managed to bring the cost of microloans to below 10% for borrowers, including interest which is paid out to lenders. However, it remains to be seen whether such radical alternative models can reach the scale necessary to compete with traditional microfinance programs.[13]

Use of Loans

Practitioners and donors from the charitable side of microfinance frequently argue for restricting microcredit to loans for productive purposes—such as to start or expand a microenterprise. Those from the private-sector side respond that, because money is fungible, such a restriction is impossible to enforce, and that in any case it should not be up to rich people to determine how poor people use their money.

Reach versus Depth of Impact

There has been a long-standing debate over the sharpness of the trade-off between 'outreach' (the ability of a microfinance institution to reach poorer and more remote people) and its 'sustainability' (its ability to cover its operating costs—and possibly also its costs of serving new clients—from its operating revenues). Although it is generally agreed that microfinance practitioners should seek to balance these goals to some extent, there are a wide variety of strategies, ranging from the minimalist profit-orientation of BancoSol in Bolivia to the highly integrated not-for-profit orientation of BRAC in Bangladesh. This is true not only for individual institutions, but also for governments engaged in developing national microfinance systems.

Gender

Microfinance experts generally agree that women should be the primary focus of service delivery. Evidence shows that they are less likely to default on their loans than men. Industry data from 2006 for 704 MFIs reaching 52 million borrowers includes MFIs using the solidarity lending methodology (99.3% female clients) and MFIs using individual lending (51% female clients). The delinquency rate for solidarity lending was 0.9% after 30 days (individual lending—3.1%), while 0.3% of loans were written off (individual lending—0.9%).[14] Because operating margins become tighter the smaller the loans delivered, many MFIs consider the risk of lending to men to be too high. This focus on women is questioned sometimes, however a recent study of microenterpreneurs from Sri Lanka published by the World Bank found that the return on capital for male-owned businesses (half of the sample) averaged 11%, whereas the return for women-owned businesses was 0% or slightly negative.[15]

Microfinance's emphasis on female-oriented lending is the subject of controversy, as it is claimed that microfinance improves the status of women through an alleviation of poverty. It is argued that by providing women with initial capital, they will be able to support themselves independent of men, in a manner which would encourage sustainable growth of enterprise and eventual self-sufficiency. This claim has yet to be proven in any substantial form. Moreover, the attraction of women as a potential investment base is precisely because they are constrained by socio-cultural norms regarding such concepts of obedience, familial duty, household maintenance and passivity.[16] The result of these norms is that while micro-lending may enable women to improve their daily subsistence to a more steady pace, they will not be able to engage in market-oriented business practice beyond a limited scope of low-skilled, low-earning, informal work.[17] Part of this is a lack of permissivity in the society; part a reflection of the added burdens of household maintenance that women shoulder alone as a result of microfinancial empowerment; and part a lack of training and education surrounding gendered conceptions of economics. In particular, the shift in norms such that women continue to be responsible for all the domestic private sphere labour as well as undertaking public economic support for their families, independent of male aid increases rather than decreases burdens on already limited persons.

If there were to be an exchange of labour, or if women's income were supplemental rather than essential to household maintenance, there might be some truth to claims of establishing long-term businesses; however when so constrained it is impossible for women to do more than pay off a current loan only to take on another in a cyclic pattern which is beneficial to the financier but hardly to the borrower. This gender essentializing crosses over from institutionalized lenders such as the Grameen Bank into interpersonal direct lending through charitable crowd-funding operations, such as Kiva. More recently, the popularity of non-profit global online lending has grown, suggesting that a redress of gender norms might be instituted through individual selection fomented by the processes of such programs, but the reality is as yet uncertain. Studies have noted that the likelihood of lending to women, individually or in groups, is 38% higher than rates of lending to men.[18]

This is also due to a general trend for interpersonal microfinance relations to be conducted on grounds of similarity and internal/external recognition: lenders want to see something familiar, something supportable in potential borrowers, so an emphasis on family, goals of education and health, and a commitment to community all achieve positive results from prospective financiers.[19] Unfortunately, these labels disproportionately align with women rather than men, particularly in the developing world. The result is that microfinance continues to rely on restrictive gender norms rather than seek to subvert them through economic redress in terms of foundation change: training, business management and financial education are all elements which might be included in parameters of female-aimed loans and until they are the fundamental reality of women as a disadvantaged section of societies in developing states will go untested.

Benefits and Limitations

Microfinancing produces many benefits for poverty stricken, or low- income households. One of the benefits is that it is very accessible. Banks today simply won’t extend loans to those with little to no assets, and generally don’t engage in small size loans typically associated with microfinancing. Through microfinancing small loans are produced and accessible. Microfinancing is based on the philosophy that even small amounts of credit can help end the cycle of poverty. Another benefit produced from the microfinancing initiative is that it presents opportunities, such as extending education and jobs. Families receiving microfinancing are less likely to pull their children out of school for economic reasons. As well, in relation to employment, people are more likely to open small businesses that will aid the creation of new jobs. Overall, the benefits outline that the microfinancing initiative is set out to improve the standard of living amongst impoverished communities (Rutherford, 2009).

There are also many challenges within microfinance initiatives which may be social or financial. Here, more articulate and better-off community members may cheat poorer or less-educated neighbours. This may occur intentionally or inadvertently through loosely run organizations. As a result, many microfinance initiatives require a large amount of social capital or trust in order to work effectively. The ability of poorer people to save may also fluctuate over time as unexpected costs may take priority which could result in them being able to save little or nothing some weeks. Rates of inflation may cause funds to lose their value, thus financially harming the saver and not benefiting collector (Rutherford, 2009).

History of microfinance

Over the past centuries, practical visionaries, from the Franciscan monks who founded the community-oriented pawnshops of the 15th century to the founders of the European credit union movement in the 19th century (such as Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen) and the founders of the microcredit movement in the 1970s (such as Muhammad Yunus and Al Whittaker), have tested practices and built institutions designed to bring the kinds of opportunities and risk-management tools that financial services can provide to the doorsteps of poor people.[20] While the success of the Grameen Bank (which now serves over 7 million poor Bangladeshi women) has inspired the world, it has proved difficult to replicate this success. In nations with lower population densities, meeting the operating costs of a retail branch by serving nearby customers has proven considerably more challenging. Hans Dieter Seibel, board member of the European Microfinance Platform, is in favour of the group model. This particular model (used by many Microfinance institutions) makes financial sense, he says, because it reduces transaction costs. Microfinance programmes also need to be based on local funds.[21]

The history of microfinancing can be traced back as far as the middle of the 1800s, when the theorist Lysander Spooner was writing about the benefits of small credits to entrepreneurs and farmers as a way of getting the people out of poverty. Independently of Spooner, Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen founded the first cooperative lending banks to support farmers in rural Germany.[22]

The modern use of the expression "microfinancing" has roots in the 1970s when organizations, such as Grameen Bank of Bangladesh with the microfinance pioneer Muhammad Yunus, were starting and shaping the modern industry of microfinancing. Another pioneer in this sector is Akhtar Hameed Khan.

Microfinance Standards and Principles

Poor people borrow from informal moneylenders and save with informal collectors. They receive loans and grants from charities. They buy insurance from state-owned companies. They receive funds transfers through formal or informal remittance networks. It is not easy to distinguish microfinance from similar activities. It could be claimed that a government that orders state banks to open deposit accounts for poor consumers, or a moneylender that engages in usury, or a charity that runs a heifer pool are engaged in microfinance. Ensuring financial services to poor people is best done by expanding the number of financial institutions available to them, as well as by strengthening the capacity of those institutions. In recent years there has also been increasing emphasis on expanding the diversity of institutions, since different institutions serve different needs.

Some principles that summarize a century and a half of development practice were encapsulated in 2004 by CGAP and endorsed by the Group of Eight leaders at the G8 Summit on June 10, 2004:[20]

- Poor people need not just loans but also savings, insurance and money transfer services.

- Microfinance must be useful to poor households: helping them raise income, build up assets and/or cushion themselves against external shocks.

- "Microfinance can pay for itself."[23] Subsidies from donors and government are scarce and uncertain and so, to reach large numbers of poor people, microfinance must pay for itself.

- Microfinance means building permanent local institutions.

- Microfinance also means integrating the financial needs of poor people into a country's mainstream financial system.

- "The job of government is to enable financial services, not to provide them."[24]

- "Donor funds should complement private capital, not compete with it."[24]

- "The key bottleneck is the shortage of strong institutions and managers."[24] Donors should focus on capacity building.

- Interest rate ceilings hurt poor people by preventing microfinance institutions from covering their costs, which chokes off the supply of credit.

- Microfinance institutions should measure and disclose their performance—both financially and socially.

Microfinance is considered a tool for socio-economic development, and can be clearly distinguished from charity. Families who are destitute, or so poor they are unlikely to be able to generate the cash flow required to repay a loan, should be recipients of charity. Others are best served by financial institutions.

Scale of Microfinance Operations

No systematic effort to map the distribution of microfinance has yet been undertaken. A benchmark was established by an analysis of 'alternative financial institutions' in the developing world in 2004.[25] The authors counted approximately 665 million client accounts at over 3,000 institutions that are serving people who are poorer than those served by the commercial banks. Of these accounts, 120 million were with institutions normally understood to practice microfinance. Reflecting the diverse historical roots of the movement, however, they also included postal savings banks (318 million accounts), state agricultural and development banks (172 million accounts), financial cooperatives and credit unions (35 million accounts) and specialized rural banks (19 million accounts).

Regionally, the highest concentration of these accounts was in India (188 million accounts representing 18% of the total national population). The lowest concentrations were in Latin America and the Caribbean (14 million accounts representing 3% of the total population) and Africa (27 million accounts representing 4% of the total population, with the highest rate of penetration in West Africa, and the highest growth rate in Eastern and Southern Africa [26] ). Considering that most bank clients in the developed world need several active accounts to keep their affairs in order, these figures indicate that the task the microfinance movement has set for itself is still very far from finished.

By type of service, "savings accounts in alternative finance institutions outnumber loans by about four to one. This is a worldwide pattern that does not vary much by region."[27]

An important source of detailed data on selected microfinance institutions is the MicroBanking Bulletin, which is published by Microfinance Information Exchange. At the end of 2009, it was tracking 1,084 MFIs that were serving 74 million borrowers ($38 billion in outstanding loans) and 67 million savers ($23 billion in deposits).[28]

Another source of information regarding the environment of microfinance is the Global Microscope on the Microfinance Business Environment,[29] prepared by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), the Inter-American Development Bank, and others. The 2011 report contains information on the environment of microfinance in 55 countries among two categories, Regulatory Framework and the Supporting Institutional Framework.[30] This publication, also known as the Microscope, was first developed in 2007, focusing only on Latin America and the Caribbean, but by 2009, this report had become a global study.[31]

As yet there are no studies that indicate the scale or distribution of 'informal' microfinance organizations like ROSCA's and informal associations that help people manage costs like weddings, funerals and sickness. Numerous case studies have been published, however, indicating that these organizations, which are generally designed and managed by poor people themselves with little outside help, operate in most countries in the developing world.[32]

Help can come in the form of more and better-qualified staff, thus higher education is needed for microfinance institutions. This has begun in some universities, as Oliver Schmidt describes. Mind the management gap

Microfinance in the United States and Canada

In Canada and the US, microfinance organizations target marginalized populations unable to access mainstream bank financing. Close to 8% of Americans are unbanked, meaning around 9 million are without any kind of bank account or formal financial services.[33] Most of these institutions are structured as nonprofit organizations.[34] Microloans in the U.S. context is defined as the extension of credit up to $50,000.[35] In Canada, CRA guidelines restrict microfinance loans to a maximum of $25,000.[36] The average microfinance loan size in the US is US$9,732, ten times the size of an average microfinance loan in developing countries (US$973).[34]

Impact

While all microfinance institutions aim at increasing incomes and employment, in developing countries the empowerment of women, improved nutrition and improved education of the borrower’s children are frequently aims of microfinance institutions. In the US and Canada, aims of microfinance include the graduation of recipients from welfare programs and an improvement in their credit rating. In the US, microfinance has created jobs directly and indirectly, as 60% of borrowers were able to hire others.[37] According to reports, every domestic microfinance loan creates 2.4 jobs.[38] These entrepreneurs provide wages that are, on average, 25% higher than minimum wage.[38] Small business loans eventually allow small business owners to make their businesses their primary source of income, with 67% of the borrowers showing a significant increase in their income as a result of their participation in certain micro-loan programs.[37] In addition, these business owners are able to improve their housing situation, 70% indicating their housing has improved.[37] Ultimately, many of the small business owners that use social funding are able to graduate from government funding.[37]

United States

In the late 1980s, microfinance institutions developed in the United States. They served low-income and marginalized minority communities. By 2007, there were 500 microfinance organizations operating in the US with 200 lending capital.[34]

There were three key factors that triggered the growth in domestic microfinance:

- Change in social welfare policies and focus on economic development and job creation at the macro level.

- Encouragement of employment, including self-employment, as a strategy for improving the lives of the poor.

- The increase in the proportion of Latin American and Asian immigrants who came from societies where microenterprises are prevalent.

These factors incentivized the public and private supports to have microlending activity in the United States.[34]

Selected microfinance institutions in the United States are:

The Accion U.S. Network, an affiliate of Accion International, offers microloans and other financial services to low- and moderate-income entrepreneurs for their small businesses who cannot get financial support through traditional means.

Founded in 1997 in New York City, Project Enterprise provides support to entrepreneurs and small businesses in lower income communities through access to business loans, business development services, and networking opportunities.

Based in New York and founded by Muhammed Yunus, Grameen America provides micro-loans, savings programs, financial education, and credit establishment to low-income entrepreneurs.

An example of a Microfinance startup, this organization was founded by two Brown University students in 2009. Based in Providence, Rhode Island, CGF provides credit-building business and consumer loans, financial coaching, and free tax preparation.

- RISE Financial Pathways (formerly Community Financial Resource Center)

Based in Los Angeles, this first public-private partnership of its kind provides micro-loans, SEED/expansion loans, high interest savings accounts, financial education & counseling to low and moderate income entrepreneurs and disinvested communities.[39]

Canada

Microfinance in Canada took shape through the development of credit unions. These credit unions provided financial services to the Canadians who could not get access to traditional financial means. Two separate branches of credit unions developed in Canada to serve the financially marginalized segment of the population. Alphonse Desjardins introduced the establishment of savings and credit services in late 1900 to the Quebecois who did not have financial access. Approximately 30 years later Father Moses Coady introduced credit unions to Nova Scotia. These were the models of the modern institutions still present in Canada today.[40]

Efforts to transfer specific microfinance innovations such as solidarity lending from developing countries to Canada have met with little success.[41]

Selected microfinance institutions in Canada are:

Founded by Sandra Rotman in 2009, Rise is a Rotman and CAMH initiative that provides small business loans, leases, and lines of credit to entrepreneurs with mental health and/or addiction challenges.

Formed in 2005 through the merging of the Civil Service Savings and Loan Society and the Metro Credit Union, Alterna is a financial alternative to Canadians. Their banking policy is based on cooperative values and expert financial advising.

- Access Community Capital Fund

Based in Toronto, Ontario, ACCESS is a Canadian charity that helps entrepreneurs without collateral or credit history find affordable small loans.

- Montreal Community Loan Fund

Created to help eradicate poverty, Montreal Community Loan Fund provides accessible credit and technical support to entrepreneurs with low income or credit for start-ups or expansion of organizations that cannot access traditional forms of credit.

- Momentum

Using the community economic development approach, Momentum offers opportunities to people living in poverty in Calgary. Momentum provides individuals and families who want to better their financial situation take control of finances, become computer literate, secure employment, borrow and repay loans for business, and purchase homes.

Founded in 1946, Vancity is now the largest English speaking credit union in Canada.

Limitations

Complications specific to Canada include the need for loans of a substantial size in comparison to the ones typically seen in many international microfinance initiatives. Microfinance is also limited by the rules and limitations surrounding money-lending. For example, Canada Revenue Agency limits the loans made in these sort of transactions to a maximum of $25,000. As a result, many people look to banks to provide these loans. Also, microfinance in Canada is driven by profit which, as a result, fails to advance the social development of community members. Within marginalized or impoverished Canadian communities, banks may not be readily accessible to deposit or take out funds. These banks which would have charged little or no interest on small amounts of cash are replaced by lending companies. Here, these companies may charge extremely large interest rates to marginalized community members thus increasing the cycle of poverty and profiting off of another’s loss (Rutherford, 2009).

In Canada, microfinancing competes with pay-day loans institutions which take advantage of marginalized and low-income individuals by charging extremely high, predatory interest rates. Communities with low social capital often don't have the networks to implement and support microfinance initiatives, leading to the proliferation of pay day loan institutions. Pay day loan companies are unlike traditional microfinance in that they don't encourage collectivism and social capital building in low income communities, however exist solely for profit.

Micro Finance on the Indian Subcontinent

Loans to poor people by banks have many limitations including lack of security and high operating costs. As a result, microfinance was developed as an alternative to provide loans to poor people with the goal of creating financial inclusion and equality.

Muhammad Yunus, a Nobel Prize winner, introduced the concept of Microfinance in Bangladesh in the form of the "Grameen Bank". The National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) took this idea and started the concept of microfinance in India. Under this mechanism, there exists a link between SHGs (Self-help groups), NGOs and banks. SHGs are formed and nurtured by NGOs and only after accomplishing a certain level of maturity in terms of their internal thrift and credit operations are they entitled to seek credit from the banks. There is an involvement from the concerned NGO before and even after the SHG-Bank linkage. The SHG-Bank linkage programme, which has been in place since 1992 in India, has provided about 22.4 lakh for SHG finance by 2006. It involves commercial banks, regional rural banks (RRBs) and cooperative banks in its operations.

Microfinance is defined as, financial services such as savings accounts, insurance funds and credit provided to poor and low income clients so as to help them increase their income, thereby improving their standard of living.

In this context the main features of microfinance are:

- Loan given without security

- Loans to those people who live below the poverty line

- Members of SHGs may benefit from micro finance

- Maximum limit of loan under micro finance ₨25,000/-

- Terms and conditions offered to poor people are decided by NGOs

- Microfinance is different from Microcredit- under the latter, small loans are given to the borrower but under microfinance alongside many other financial services including savings accounts and insurance. Therefore, microfinance has a wider concept than microcredit.

In June 2014, CRISIL released its latest report on the Indian Microfinance Sector titled "India's 25 Leading MFI's".[42] This list is the most comprehensive and up to date overview of the microfinance sector in India and the different microfinance institutions operating in the sub-continent.

Many loan officers in India create emotional connection with borrowers before loan reaches maturity by mentioning details about borrowers’ personal life and family and also demonstrating affection in many different ways as a strategy to generate pressure during recovery.[43]

Inclusive financial systems

The microcredit era that began in the 1970s has lost its momentum, to be replaced by a 'financial systems' approach. While microcredit achieved a great deal, especially in urban and near-urban areas and with entrepreneurial families, its progress in delivering financial services in less densely populated rural areas has been slow.

The new financial systems approach pragmatically acknowledges the richness of centuries of microfinance history and the immense diversity of institutions serving poor people in developing world today. It is also rooted in an increasing awareness of diversity of the financial service needs of the world’s poorest people, and the diverse settings in which they live and work.

Brigit Helms in her book 'Access for All: Building Inclusive Financial Systems', distinguishes between four general categories of microfinance providers, and argues for a pro-active strategy of engagement with all of them to help them achieve the goals of the microfinance movement.[44]

- Informal financial service providers

- These include moneylenders, pawnbrokers, savings collectors, money-guards, ROSCAs, ASCAs and input supply shops. Because they know each other well and live in the same community, they understand each other’s financial circumstances and can offer very flexible, convenient and fast services. These services can also be costly and the choice of financial products limited and very short-term. Informal services that involve savings are also risky; many people lose their money.

- Member-owned organizations

- These include self-help groups, credit unions, and a variety of hybrid organizations like 'financial service associations' and CVECAs. Like their informal cousins, they are generally small and local, which means they have access to good knowledge about each other's financial circumstances and can offer convenience and flexibility. Grameen Bank is a member-owned organization. Since they are managed by poor people, their costs of operation are low. However, these providers may have little financial skill and can run into trouble when the economy turns down or their operations become too complex. Unless they are effectively regulated and supervised, they can be 'captured' by one or two influential leaders, and the members can lose their money.

- NGOs

- The Microcredit Summit Campaign counted 3,316 of these MFIs and NGOs lending to about 133 million clients by the end of 2006.[45] Led by Grameen Bank and BRAC in Bangladesh, Prodem in Bolivia, Opportunity International, and FINCA International, headquartered in Washington, DC, these NGOs have spread around the developing world in the past three decades; others, like the Gamelan Council, address larger regions. They have proven very innovative, pioneering banking techniques like solidarity lending, village banking and mobile banking that have overcome barriers to serving poor populations. However, with boards that don’t necessarily represent either their capital or their customers, their governance structures can be fragile, and they can become overly dependent on external donors.

- Formal financial institutions

- In addition to commercial banks, these include state banks, agricultural development banks, savings banks, rural banks and non-bank financial institutions. They are regulated and supervised, offer a wider range of financial services, and control a branch network that can extend across the country and internationally. However, they have proved reluctant to adopt social missions, and due to their high costs of operation, often can't deliver services to poor or remote populations. The increasing use of alternative data in credit scoring, such as trade credit is increasing commercial banks' interest in microfinance.[46]

With appropriate regulation and supervision, each of these institutional types can bring leverage to solving the microfinance problem. For example, efforts are being made to link self-help groups to commercial banks, to network member-owned organizations together to achieve economies of scale and scope, and to support efforts by commercial banks to 'down-scale' by integrating mobile banking and e-payment technologies into their extensive branch networks.

Microcredit and the Web

Due to the unbalanced emphasis on credit at the expense of microsavings, as well as a desire to link Western investors to the sector, peer-to-peer platforms have developed to expand the availability of microcredit through individual lenders in the developed world. New platforms that connect lenders to micro-entrepreneurs are emerging on the Web, for example MYC4, Kiva, Zidisha, myELEN, Opportunity International and the Microloan Foundation. Another Web-based microlender United Prosperity uses a variation on the usual microlending model; with United Prosperity the micro-lender provides a guarantee to a local bank which then lends back double that amount to the micro-entrepreneur. In 2009, the US-based nonprofit Zidisha became the first peer-to-peer microlending platform to link lenders and borrowers directly across international borders without local intermediaries.[47]

The volume channeled through Kiva's peer-to-peer platform is about $100 million as of November 2009 (Kiva facilitates approximately $5M in loans each month). In comparison, the needs for microcredit are estimated about 250 bn USD as of end 2006.[48] Most experts agree that these funds must be sourced locally in countries that are originating microcredit, to reduce transaction costs and exchange rate risks.

There have been problems with disclosure on peer-to-peer sites, with some reporting interest rates of borrowers using the flat rate methodology instead of the familiar banking Annual Percentage Rate.[49] The use of flat rates, which has been outlawed among regulated financial institutions in developed countries, can confuse individual lenders into believing their borrower is paying a lower interest rate than, in fact, they are.

Microfinance and Social Interventions

There are currently a few social interventions that have been combined with micro financing to increase awareness of HIV/AIDS. Such interventions like the "Intervention with Microfinance for AIDS and Gender Equity" (IMAGE) which incorporates microfinancing with "The Sisters-for-Life" program a participatory program that educates on different gender roles, gender-based violence, and HIV/AIDS infections to strengthen the communication skills and leadership of women [50] "The Sisters-for-Life" program has two phases where phase one consists of ten one-hour training programs with a facilitator with phase two consisting of identifying a leader amongst the group, train them further, and allow them to implement an Action Plan to their respective centres.

Microfinance has also been combined with business education and with other packages of health interventions.[51] A project undertaken in Peru by Innovations for Poverty Action found that those borrowers randomly selected to receive financial training as part of their borrowing group meetings had higher profits, although there was not a reduction in "the proportion who reported having problems in their business".[52] Pro Mujer, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) with operations in five Latin American countries, combines microfinance and healthcare. This approach shows, that microfinance can not only help businesses to prosper; it can also foster human development and social security. Pro Mujer uses a "one-stop shop" approach, which means in one building, the clients find financial services, business training, empowerment advice and healthcare services combined.[53]

Impact and Criticism

Most criticisms of microfinance have actually been criticisms of microcredit. Criticism focuses on the impact on poverty, the level of interest rates, high profits, overindebtedness and suicides. Other criticism include the role of foreign donors and working conditions in companies affiliated to microfinance institutions, particularly in Bangladesh.

Impact

The impact of microcredit is a subject of much controversy. Proponents state that it reduces poverty through higher employment and higher incomes. This is expected to lead to improved nutrition and improved education of the borrowers' children. Some argue that microcredit empowers women. In the US and Canada, it is argued that microcredit helps recipients to graduate from welfare programs.

Critics say that microcredit has not increased incomes, but has driven poor households into a debt trap, in some cases even leading to suicide. They add that the money from loans is often used for durable consumer goods or consumption instead of being used for productive investments, that it fails to empower women, and that it has not improved health or education. Moreover, as the access to micro-loans is widespread, borrowers tend to acquire several loans from different companies, making it nearly impossible to pay the debt back.[54] As a result of such tragic events, microfinance institutions in India have agreed on setting an interest rate ceiling of 15 percent.[55] This is important because microfinance loan recipients have a higher level of security in repaying the loans and a lower level of risk in failing to repay them.

The available evidence indicates that in many cases microcredit has facilitated the creation and the growth of businesses. It has often generated self-employment, but it has not necessarily increased incomes after interest payments. In some cases it has driven borrowers into debt traps. There is no evidence that microcredit has empowered women. In short, microcredit has achieved much less than what its proponents said it would achieve, but its negative impacts have not been as drastic as some critics have argued. Microcredit is just one factor influencing the success of small businesses, whose success is influenced to a much larger extent by how much an economy or a particular market grows. For example, local competition in the area of lack of a domestic markets for certain goods can influence how successful small businesses who receive microcredit are.

Mission Drift in Microfinance

Mission drift refers to the phenomena through which the MFIs or the micro finance institutions increasingly try to cater to customers who are better off than their original customers, primarily the poor families. Roy Mersland and R. Øystein Strøm in their research on Mission Drift suggest that this selection bias can come not only through an increase in the average loan size, which allows for financially stronger individuals to get the loans, but also through MFI's particular lending methodology, main market of operation, or even the gender bias as further mission drift measures.[56] And as it may follow, this selective funding would lead to lower risks and lower costs for the firm.

However, economists Beatriz Armendáriz and Ariane Szafarz suggests that this phenomenon is not driven by cost minimization alone. She suggests that it happens because of the interplay between the company’s mission, the cost differential between poor and unbanked wealthier clients and region specific characteristics pertaining the heterogeneity of their clientele.[57] But in either way, this problem of selective funding leads to an ethical tradeoff where on one hand there is an economic reason for the company to restrict its loans to only the individuals who qualify the standards, and on the other hand there is an ethical responsibility to help the poor people get out of poverty through the provision of capital.

Role of foreign donors

The role of donors has also been questioned. CGAP recently commented that "a large proportion of the money they spend is not effective, either because it gets hung up in unsuccessful and often complicated funding mechanisms (for example, a government apex facility), or it goes to partners that are not held accountable for performance. In some cases, poorly conceived programs have retarded the development of inclusive financial systems by distorting markets and displacing domestic commercial initiatives with cheap or free money."[58]

Working Conditions in Enterprises Affiliated to MFIs

There has also been criticism of microlenders for not taking more responsibility for the working conditions of poor households, particularly when borrowers become quasi-wage labourers, selling crafts or agricultural produce through an organization controlled by the MFI. The desire of MFIs to help their borrower diversify and increase their incomes has sparked this type of relationship in several countries, most notably Bangladesh, where hundreds of thousands of borrowers effectively work as wage labourers for the marketing subsidiaries of Grameen Bank or BRAC. Critics maintain that there are few if any rules or standards in these cases governing working hours, holidays, working conditions, safety or child labour, and few inspection regimes to correct abuses.[59] Some of these concerns have been taken up by unions and socially responsible investment advocates.

See also

- Alternative data

- Chit fund

- Credit union

- Crowd funding

- Market Governance Mechanisms

- Microcredit

- Microcredit for water supply and sanitation

- Microfin360 - MIS & AIS for MFI

- Microfinance in Tanzania

- Microfinance organizations

- Microgrant

- Microinsurance

- MifosX - MIS for MFI

- Opportunity finance

- Pawnbroker

- Rotating savings and credit association (ROSCA)

- Savings bank

- Assessment Fund

- Tikkun Olam Microfinance

Notes

- ↑ Robert Peck Christen, Richard Rosenberg & Veena Jayadeva. Financial institutions with a double-bottom line: implications for the future of microfinance. CGAP Occasional Paper, July 2004, pp. 2-3.

- ↑ Feigenberg, Benjamin; Erica M. Field; Rohan Pande. "Building Social Capital Through MicroFinance". NBER Working Paper No. 16018. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ↑ Rutherford, Stuart; Arora, Sukhwinder (2009). The poor and their money: micro finance from a twenty-first century consumer's perspective. Warwickshire, UK: Practical Action. p. 4. ISBN 9781853396885.

- ↑ Hermes, N. (2014). Does microfinance affect income inequality? Applied Economics, 46(9), 1021-1034. doi:10.1080/00036846.2013.864039

- ↑ Khandker, Shahidur R. (1999). Fighting poverty with microcredit: experience in Bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh: The University Press Ltd. p. 78. ISBN 9789840514687.

- ↑ Wright, Graham A. N.; Mutesasira, Leonard K. (September 2001). "The relative risks to the savings of poor people". Small Enterprise Development (Practical Action Publishing) 12 (3): 33–45. doi:10.3362/0957-1329.2001.031.

- ↑ MacFarquhar, Neil (2010-04-13). "Banks Making Big Profits From Tiny Loans". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Kiva Help - Interest Rate Comparison". Kiva.org. Retrieved October 10, 2009.

- ↑ "About Microfinance". Kiva. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ↑ Geoffrey Muzigiti, Oliver Schmidt (January 2013). "Moving forward". D+C Development and Cooperation/ dandc.eu.

- ↑ "Microfinance: Do the micro-loans contribute to the well-being of the people or do they leave them even poorer due to high interest rates?". Quora. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ↑ Roodman, David. "Due Diligence: An Impertinent Inquiry Into Microfinance." Center for Global Development, 2011.

- ↑ Katic, Gordon (2013-02-20). "Micro-finance, Lending a Hand to the Poor?". Terry.ubc.ca. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ↑ Microfinance Information Exchange, Inc. (2007-08-01). "MicroBanking Bulletin Issue #15, Autumn, 2007, pp. 46,49". Microfinance Information Exchange, Inc. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- ↑ McKenzie, David (2008-10-17). "Comments Made at IPA/FAI Microfinance Conference Oct. 17 2008". Philanthropy Action. Retrieved 2008-10-17.

- ↑ Bruton,Chavez & Khavul, G.D.,H. & S. (2011). "Microlending in emerging economies:building a new line of inquiry from the ground up". Journal of International Buisness -Studies 42 (5): 718–739.

- ↑ Bee, Beth (2011). "Gender, solidarity and the paradox of microfinance: Reflections from Bolivia". Gender, Place & Culture 18 (1): 23–43.

- ↑ Ly & Mason, P. & G. (2012). "Individual preference over development projects:evidence from microlending on Kiva". Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Non-Profit Organizations 23 (4): 1036–1055.

- ↑ Allison, Davis, Short & Webb, T.H.,B.C.,J.C., & J.W. (2015). "Crowdfunding in a prosocial microlending environment: examining the role of intrinsic versus extrinsic cues". Entrepreneurship 39 (1): 53–73.

- 1 2 Helms, Brigit (2006). Access for All: Building Inclusive Financial Systems. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank. ISBN 0-8213-6360-3.

- ↑ Archived December 14, 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Archived August 10, 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Helms (2006), p. xi

- 1 2 3 Helms (2006), p. xii

- ↑ Robert Peck Christen, Richard Rosenberg & Veena Jayadeva. Financial institutions with a double-bottom line: implications for the future of microfinance. CGAP Occasional Paper, July 2004.

- ↑ MFW4A - Microfinance (2010-11-05). "MFW4A - Microfinance".

- ↑ Christen, Rosenberg & Jayadeva. Financial institutions with a double-bottom line, pp. 5-6

- ↑ Microfinance Information Exchange, Inc. (2009-12-01). "MicroBanking Bulletin Issue #19, December 2009, pp. 49". Microfinance Information Exchange, Inc.

- ↑ Global microscope on the microfinance business environment 2011: an index and study by the Economist Intelligence Unit (pdf) (Report). Economist Intelligence Unit Ltd. 2011.

- ↑ "Latin America tops Global Microscope Index on the microfinance business environment 2011". IDB. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Global Microscope on the Microfinance Business Environment 2011". IDB. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ↑ See for example Joachim de Weerdt, Stefan Dercon, Tessa Bold and Alula Pankhurst, Membership-based indigenous insurance associations in Ethiopia and Tanzania For other cases see ROSCA. Archived July 10, 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "FDIC: 2011 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households". Fdic.gov. 2012-12-26. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- 1 2 3 4 Pollinger, J. Jordan; Outhwaite, John; Cordero-Guzmán, Hector (1 January 2007). "The Question of Sustainability for Microfinance Institutions". Journal of Small Business Management 45 (1): 23–41. doi:10.1111/j.1540-627X.2007.00196.x.

- ↑ Hedgespeth, Grady. "SBA Information Notice" (PDF). SBA.

- ↑ "Registered Charities: Community Economic Development Programs". Archived from the original on December 6, 2005.

- 1 2 3 4 Alterna (2010). "Strengthening our community by empowering individuals.".

- 1 2 Harman, Gina (2010-11-08). "PM BIO Become a Fan Get Email Alerts Bloggers' Index How Microfinance Is Fueling A New Small Business Wave". Huffington Post.

- ↑ "RISE | Financial Pathways " A Los Angeles Microfinance Organization". Risela.org. 2013-10-17. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ↑ Reynolds, Chantelle; Christian Novak (May 19, 2011). "Low Income Entrepreneurs and their Access to Financing in Canada, Especially in the Province of Quebec/City of Montreal".

- ↑ See for example Cheryl Frankiewicz Calmeadow Metrofund: a Canadian experiment in sustainable microfinance, Calmeadow Foundation, 2001.

- ↑ Top Microfinance Institutions in India for 2014 CRISIL Report, June 2014.

- ↑ Kar, S. (2013). Recovering debts: Microfinance loan officers and the work of "proxy-creditors" in India. Journal of the American Ethnological Society, 40(3), 480-493. doi:10.1111/amet.12034

- ↑ Brigit Helms. Access for All: Building Inclusive Financial Systems. CGAP/World Bank, Washington, 2006, pp. 35-57.

- ↑ "''State of the Microcredit Summit Campaign Report 2007'', Microcredit Summit Campaign, Washington, 2007.". Microcreditsummit.org. 2006-12-31. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ↑ Turner, Michael, Robin Varghese, et al. Information Sharing and SMME Financing in South Africa, Political and Economic Research Council (PERC), p58.

- ↑ "Zidisha Set to "Expand" in Peer-to-Peer Microfinance", Microfinance Focus, Feb 2010 Archived October 8, 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Microfinance: An emerging investment opportunity. Deutsche Bank Research. December 19, 2007.

- ↑ Waterfield, Chuck. Why We Need Transparent Pricing in Microfinance. MicroFinance Transparency. 11 November 2008. Archived March 25, 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Kim, J.C., Watts, C. H., Hargreaves, J. R., Ndhlovu, L. X., Phetla, G., Morison, L. A., et al. (2007). Understanding the impact of a microfinance-based intervention of women's empowerment and the reduction of intimate partner violence in South Africa. American Journal of Public Health.

- ↑ Smith, Stephen C. (April 2002). "Village banking and maternal and child health: evidence from Ecuador and Honduras". World Development (Elsevier) 30 (4): 707–723. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(01)00128-0.

- ↑ Karlan, Dean S.; Valdivia, Martin (May 2011). "Teaching entrepreneurship: Impact of business training on microfinance clients and institutions". The Review of Economics and Statistics (MIT Press) 93 (2): 510–527. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00074. Pdf.

- ↑ Sölle de Hilari, Caroline (11 October 2013). "Microinsurance: Healthy clients" (Digital magazine). D+C Development and Cooperation (Germany: Engagement Global – Service for Development Initiatives). Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ↑ Biswas, Soutik (December 16, 2010). "India's micro-finance suicide epidemic". , BBC News. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- ↑ Sundaresan, S. (2008). Microfinance emerging trends and challenges (pp. 15-16). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. 978-1847209207

- ↑ Mersland, Roy; Strøm, R. Øystein (January 2010). "Microfinance mission drift?". World Development (Elsevier) 38 (1): 28–36. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.05.006.

- ↑ Armendáriz, Beatriz; Szafarz, Ariane (2011), "On mission drift in microfinance institutions", in Armendáriz, Beatriz; Labie, Marc, The handbook of microfinance, Singapore Hackensack, New Jersey: World Scientific, pp. 341–366, ISBN 9789814295659.

- ↑ Brigit Helms. Access for All: Building Inclusive Financial Systems. CGAP/World Bank, Washington, 2006, p. 97.

- ↑ Chowdhury, Farooque (June 24, 2007). "The metamorphosis of the micro-credit debtor". New Age (Dhaka). Archived from the original on April 10, 2008.

Further reading

- Adams, Dale W.; Graham, Douglas H.; Von Pischke, J. D. (1984). Undermining rural development with cheap credit. Boulder, Colorado and London: Westview Press. ISBN 9780865317680.

- Armendáriz, Beatriz; Morduch, Jonathan (2010) [2005]. The economics of microfinance (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262513982.

- Bateman, Milford (2010). Why doesn't microfinance work? The destructive rise of local neoliberalism. London: Zed Books. ISBN 9781848133327.

- Branch, Brian; Klaehn, Janette (2002). Striking the balance in microfinance: a practical guide to mobilizing savings. Washington, DC: Published by Pact Publications for World Council of Credit Unions. ISBN 9781888753264.

- De Mariz, Frederic; Reille, Xavier; Rozas, Daniel (July 2011). Discovering Limits. Global Microfinance Valuation Survey 2011, Washington DC: Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) World Bank.

- Dichter, Thomas; Harper, Malcolm (2007). What's wrong with microfinance. Rugby, Warwickshire, UK: Practical Action Publishing. ISBN 9781853396670.

- Dowla, Asif; Barua, Dipal (2006). The poor always pay back: the Grameen II story. Bloomfield, Connecticut: Kumarian Press Inc. ISBN 9781565492318.

- Floro, Sagrario; Yotopoulos, Pan A. (1991). Informal credit markets and the new institutional economics: the case of Philippine agriculture. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 9780813381367.

- Gibbons, David S. (1994) [1992]. The Grameen reader. Dhaka, Bangladesh: Grameen Bank. OCLC 223123405.

- Hirschland, Madeline (2005). Savings services for the poor: an operational guide. Bloomfield, Connecticut: Kumarian Press Inc. ISBN 9781565492097.

- Jafree, Sara Rizvi; Ahmad, Khalil (December 2013). "Women microfinance users and their association with improvement in quality of life: evidence from Pakistan". Asian Women (Research Institute of Asian Women (RIAW)) 29 (4): 73–105. doi:10.14431/aw.2013.12.29.4.73.

- Khandker, Shahidur R. (1999). Fighting poverty with microcredit: experience in Bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh: The University Press Ltd. ISBN 9789840514687.

- Krishna, Sridhar (2008). Micro-enterprises: perspectives and experiences. Hyderabad, India: ICFAI University Press. OCLC 294882711.

- Ledgerwood, Joanna; White, Victoria (2006). Transforming microfinance institutions providing full financial services to the poor. Washington, DC Stockholm: World Bank MicroFinance Network Sida. ISBN 9780821366158.

- Mas, Ignacio; Kumar, Kabir (July 2008). Banking on mobiles: why, how, for whom? (Report). Washington, DC: Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) World Bank.

CGAP Focus Note, No. 48

Pdf. - O'Donohoe, Nick; De Mariz, Frederic; Littlefield, Elizabeth; Reille, Xavier; Kneiding, Christoph (February 2009). Shedding Light on Microfinance Equity Valuation: Past and Present, Washington DC: Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP), World Bank.

- Rai, Achintya; et al. (2012). Venture: a collection of true microfinance stories. Zidisha Microfinance.

(Kindle E-Book)

- Raiffeisen, Friedrich Wilhelm (author); Engelmann, Konrad (translator) (1970) [1866]. The credit unions (Die Darlehnskassen-Vereine). Neuwied on the Rhine, Germany: The Raiffeisen Printing & Publishing Company. OCLC 223123405.

- Robinson, Marguerite S. (2001). The microfinance revolution. Washington, D.C. New York: World Bank Open Society Institute. ISBN 9780821345245.

- Roodman, David (2012). Due diligence an impertinent inquiry into microfinance. Washington DC: Center for Global Development. ISBN 9781933286488.

- Seibel, Hans Dieter; Khadka, Shyam (2002). "SHG banking: a financial technology for very poor microentrepreneurs". Savings and Development (Giordano Dell-Amore Foundation via JSTOR) 26 (2): 133–150. JSTOR 25830790.

- Sinclair, Hugh (2012). Confessions of a microfinance heretic: how microlending lost its way and betrayed the poor. San Francisco, California: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. ISBN 9781609945183.

- Rutherford, Stuart; Arora, Sukhwinder (2009). The poor and their money: microfinance from a twenty-first century consumer's perspective. Warwickshire, UK: Practical Action. ISBN 9781853396885.

- Wolff, Henry W. (1910) [1893]. People’s banks: a record of social and economic success (4th ed.). London: P.S. King & Son. OCLC 504828329.

- Sapovadia, Vrajlal K. (2006). "Micro finance: the pillars of a tool to socio-economic development". Development Gateway (Social Science Research Network).

- Sapovadia, Vrajlal K. (19 March 2007). "Capacity building, pillar of micro finance". Social Science Research Network. doi:10.2139/ssrn.975088.

- Sapovadia, M. (May 2013). "Microfinance and women's empowerment: a contemporary issues and challenges". International Journal of Innovative Research & Studies (IJIRS) 2 (5): 590–606. Pdf.

- Maimbo, Samuel Munzele; Ratha, Dilip (2005). Remittances development impact and future prospects. Washington, DC: World Bank. ISBN 9780821357941.

- Wright, Graham A. N. (2000). Microfinance systems: designing quality financial services for the poor. London New York Dhaka: Zed Books. ISBN 9781856497879.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs; United Nations Capital Development Fund (2006). Building inclusive financial sectors for development. New York, New York: United Nations. ISBN 9789211045611.

- Yunus, Muhammad (2007). Creating a world without poverty: social business and the future of capitalism. New York, New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 9781586484934.

- Yunus, Muhammad; Moingeon, Bertrand; Lehmann-Ortega, Laurence (April 2010). "Building social business models: lessons from the Grameen experience". Long Range Planning (Elsevier) 43 (2–3): 308–325. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2009.12.005. Pdf.

- Cooper, Logan (2015). "Small Loans, Big Promises, Unknown Impact: An Examination of Microfinance". The Apollonian Revolt. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

See also

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Microfinance. |

- Microfinance at DMOZ

- Microfinance in Asia and the Pacific: 12 Things to Know Asian Development Bank

- Accion USA's Website, a microlender for businesses in the United States

- USAID Microenterprise Results Reporting (MRR) Portal

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

|