Michael Joseph Savage

| The Right Honourable Michael Joseph Savage | |

|---|---|

|

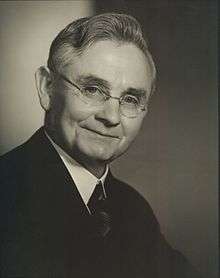

Michael Joseph Savage in the 1930s. | |

| 23rd Prime Minister of New Zealand | |

|

In office 6 December 1935 – 27 March 1940† | |

| Monarch |

George V Edward VIII George VI |

| Governor-General | George Monckton-Arundell |

| Preceded by | George Forbes |

| Succeeded by | Peter Fraser |

| Member of the New Zealand Parliament for Auckland West | |

|

In office 17 December – 27 March 1940† | |

| Preceded by | Charles Poole |

| Succeeded by | Peter Carr |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

23 March 1872 Tatong Victoria Australia |

| Died |

27 March 1940 (aged 68) Wellington New Zealand |

| Political party |

Labour (1916-40) Social Democratic (1913-16) Socialist (1907-13) |

| Spouse(s) | Never married |

| Children | None |

| Profession | Trade unionist |

| Religion |

Roman Catholic (For a time Rationalism) |

Michael Joseph Savage (23 March 1872 – 27 March 1940) was the first Labour Prime Minister of New Zealand. He is commonly known as the architect of the welfare state and generally regarded as one of New Zealand's greatest and most revered Prime Ministers. He was given the title New Zealander of the Century by The New Zealand Herald in 1999. He is the only New Zealand Prime Minister to serve under three British Monarchs (George V, Edward VIII and George VI).

Early life

Born as Michael Savage in Tatong, Victoria, Australia, the youngest of eight children of Irish immigrant parents, he received a Roman Catholic upbringing from his sister Rose, after his mother's death when he was aged five. He spent five years attending a state school at Rothesay, the same town as his father's farm. From 1886, aged 14, to 1893 Savage worked at a wine and spirits shop in Benalla.[1] Savage also attended evening classes at Benalla College at this time. Although short in stature, Savage had enormous physical strength and made a name as both a boxer and weightlifter while enjoying dancing and many other sports.

In 1891 Savage was devastated by the deaths of both his sister Rose and his closest brother Joe. He adopted Joe's name and became known as Michael Joseph Savage from then on. After losing his job in 1893, Savage moved to New South Wales, finding work as a labourer and irrigation ditch-digger in Narrandera for seven years. Whilst there, he joined the General Labourers' Union and became familiar with the radical political theories of the Americans Henry George and Edward Bellamy, who influenced his political policies in later life.[2]

Savage moved back to Victoria in 1900, working a number of jobs. He became active in the Political Labor Council of Victoria, and in 1907 he was chosen as the PLC's candidate to stand for the Wangaratta electorate. Savage had to pull out after the party was not able to fund his deposit and campaign costs, and John Thomas stood instead.[2][3][4] He remained an active party member and became a close friend of PLC member Paddy Webb, with whom he was closely linked in later years.[2]

New Zealand

After a farewell function in Rutherglen, Savage emigrated to New Zealand in 1907.[3] He arrived in Wellington on 9 October, which happened to be Labour Day. There he worked in a variety of jobs, as a miner, flax-cutter and storeman, before becoming involved in the union movement. Despite initially intending to join Webb on the West Coast, he decided to move north, arriving in Auckland in 1908.

He soon found board there with Alf and Elizabeth French and their two children. Alf had come to New Zealand in 1894 on the ship Wairarapa, which was wrecked on Great Barrier Island, and had helped in the rescue of a girl. Savage, who never married, lived with the French family until 1939, when he moved to the house Hill Haven, 64-66 Harbour View Road, Northland, Wellington, subsequently used by his successor as Prime Minister, Peter Fraser, until 1949.[5]

Savage served as patron of the New Zealand Rugby League.[6]

Political career

Savage at first opposed the formation of the original New Zealand Labour Party as he viewed the grouping as insufficiently socialistic. Instead he became the chairman of the New Zealand Federation of Labour, known as the "Red Feds".[2] There, he assisted with organizing meetings and group sessions and helped to distributed their socialist newspaper, the Maoriland Worker.

Socialist origins

In the 1911 and 1914 general election campaigns, Savage unsuccessfully stood as the Socialist candidate for Auckland Central, coming second each time to Albert Glover of the Liberal Party.[2][7] During this time Savage was also involved in local union groups, becoming president of the Auckland Brewers', Wine and Spirit Merchants' and Aerated-water Employees' Union, president of the Auckland Trades and Labour Council, the Auckland organizer for the Social Democratic Party and supported striking miners at Waihi.[2] During World War I he opposed conscription, arguing "that the conscription of wealth should precede the conscription of men".[2] Savage's opposition to conscription was not absolute, rather based on balance. Indeed he complied with a conscription order and entered a training camp in 1918, aged 46.[8]

Savage openly supported the formation of a unified New Zealand Labour Party in July 1916, and became its national vice president in 1918 and later the first permanent national secretary the next year. In 1919 Savage was elected as a Labour candidate to both the Auckland City Council and the Auckland Hospital and Charitable Aid Board in local body elections. He served on the Charitable Aid Board until 1922 and as a councillor until 1923 but was re-elected in 1927, remaining in office until 1935.[2]

Member of Parliament

| Parliament of New Zealand | ||||

| Years | Term | Electorate | Party | |

| 1919–1922 | 20th | Auckland West | Labour | |

| 1922–1925 | 21st | Auckland West | Labour | |

| 1925–1928 | 22nd | Auckland West | Labour | |

| 1928–1931 | 23rd | Auckland West | Labour | |

| 1931–1935 | 24th | Auckland West | Labour | |

| 1935–1938 | 25th | Auckland West | Labour | |

| 1938–1940 | 26th | Auckland West | Labour | |

After the war the voters of the Auckland West electorate put Savage into Parliament as a Labour member in the 1919 general election, an electorate that he held until his death.[9] He became one of eight Labour Members of Parliament. He formally became the party's deputy-leader after the 1922 election, defeating Dan Sullivan eleven votes to six.[2] Assuming an ever increasing workload, he resigned as Labour's national secretary and Auckland Labour Representation Committee secretary in July 1920.

For most of the 1920s Savage sought to expand Labour's support beyond urban unionists and travelled frequently to rural areas. He became the leading advocate for increases to pensions and universally free health care. He is credited for the creation of the Family Allowances Act 1926, which the governing Reform Party openly commented that it had modelled the legislation on three earlier defeated bills introduced by Savage.[2] In 1927 Savage and several others persuaded the party to amend its land policy and recognise the right of freehold which was essential in gaining rural support for Labour. In doing so, Savage furthered perceptions that he was a more practical politician than current Labour leader Harry Holland.[2] In October 1933 Holland died suddenly and Savage took his place becoming Labour's second party Leader. He helped engineer the Labour/Rātana alliance (formalised in 1936).

Prime Minister

During the depression, Savage toured the country, and became an iconic figure. An excellent speaker, he became the most visible politician in the land, and led Labour to victory in the 1935 election. Along with the Premiership, he appointed himself to the posts of Minister of External Affairs and Minister of Native Affairs.[10]

Despite questioning the necessity for Edward VIII to abdicate, Savage sailed to Britain in 1937 to attend the coronation of King George VI as well as the concurrent Imperial Conference. While in London, Savage differentiated himself from the other Commonwealth prime ministers when he openly criticised Britain for weakening the League of Nations and argued that the dominions were not consulted with properly on foreign policy and defence issues. Savage's government (unlike Britain) was quick to condemn German rearmament, Japanese expansion in China and Italy's conquest of Abyssinia. Britain, Australia, Canada and the opposition National Party were critical of Savage for his stance.[2]

In April 1938 Savage and Walter Nash began planning Labour's proposals on social security, in-line with their 1935 election promises. The Social Security Bill put forward by the government boasted an unemployment benefit payable to people 16 years and over; a universal free health system extending to general practitioners, public hospitals and maternity care; a means-tested old-age pension of 30 shillings a week for men and women at age 60; and universal superannuation from age 65. The act was eventually passed establishing the first ever social security system in the western world.[2] As a result of this, the first Labour government swiftly proved popular and easily won the 1938 general election with an increased popular mandate.

Savage led the country into World War II, officially declaring war on Nazi Germany on 3 September 1939, just hours after Britain.[11] Unlike Australia, which felt obligated to declare war, as it also had not ratified the Statute of Westminster, New Zealand did so as a sign of allegiance to Britain, and in recognition of Britain's abandoning its former appeasement of the dictators, a policy that New Zealand had opposed. This led to Prime Minister Savage declaring (from his sick bed) two days later:

With gratitude for the past and confidence in the future we range ourselves without fear beside Britain. Where she goes, we go; where she stands, we stand. We are only a small and young nation, but we march with a union of hearts and souls to a common destiny.[12]

Death and commemoration

Suffering from cancer of the colon at the time of the 1938 election, Savage had delayed seeking treatment, in order to participate in the election campaign. He died from the cancer in March 1940.

Savage brought an almost religious fervour to his politics. This, and his death while in office, has made him become something of an iconic figure to the Left. The architect of the welfare state (see Social welfare in New Zealand), his picture reportedly hung in many Labour supporters' homes. His popularity amongst the voting population was so celebrated that he is said to have remarked in disbelief to John A. Lee that, "They [the people] think I am God" after Labour's re-election in 1938.[13] Savage rejected rationalism in later life and returned to his Catholic roots. His state funeral included a Requiem Mass celebrated at the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Hill St, Wellington before his body was taken amidst general and public mourning by train to Auckland where he was interred initially in a temporarily adapted harbour defence gun installation. He was soon after removed to a side chapel of St Patrick's Cathedral in Auckland, while a national competition was announced, decided, and the winning design of the monumental tomb and memorial gardens at Bastion Point constructed, forming his permanent resting site. While younger generations have less awareness of him, many older New Zealanders continue to revere him.

Savage lies buried at Bastion Point on Auckland's Waitemata Harbour waterfront in the Savage Memorial,[14] a clifftop mausoleum crowned by a tall minaret, and fronted by an extensive memorial garden and reflecting pool. Savage’s body is interred in a vertical shaft below the sarcophagus, as confirmed in 2003-05.[15]

Legacy

Michael Joseph Savage is revered from many sides of the political spectrum and is known as the architect of the New Zealand Welfare State. He is considered by academics and historians to be New Zealand's most loved Prime Minister. He was often called 'Everybody's Uncle' because of his kind and friendly nature. He once helped a family in Miramar, Wellington, move their furniture into their new state home.[16]

Notes

- ↑ Hobbs 1967, pp. 32.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Gustafson, Barry. "Savage, Michael Joseph - Biography". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- 1 2 "Rutherglen". Benalla Standard. 13 September 1907. p. 3. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ↑ "North-Eastern Ensign". Benalla Ensign. 22 March 1907. p. 2. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ↑ Dominion Post (Wellington), 2012: 1 December pE1 & 26 December pA14

- ↑ Jessup, Peter (12 October 2002). "Kiwi players let their hair down at Clark bash". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ↑ Scholefield 1950, p. 109.

- ↑ Gustafson 1980, pp. 112.

- ↑ Scholefield 1950, p. 137.

- ↑ New Zealand Parliamentary Debates, Vols. 248-256 (1936-1939).

- ↑ "Fighting for Britain – NZ and the Second World War". Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 2 September 2008.

- ↑ Ministry for Culture and Heritage, "PM Declares NZ’s Support for Britain: 5 September 1939," updated 14 October 2014

- ↑ Hobbs 1967, pp. 30.

- ↑ Nathan, Simon; Bruce Hayward (27 October 2010). "Story: Building stone". Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ↑ Fletcher, Kelsey (10 February 2013). "King find recalls Savage mystery". Fairfax (Stuff). Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ Illustrated history of New Zealand by Marcia Stenson, page 55

References

- Hobbs, Leslie (1967). The Thirty-Year Wonders. Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs.

- Scholefield, Guy (1950) [First published in 1913]. New Zealand Parliamentary Record, 1840–1949 (3rd ed.). Wellington: Govt. Printer.

- Gustafson, Barry (1980). Labour's path to political independence: the origins and establishment of the NZ Labour Party 1900–1919. Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland University Press. ISBN 0-19-647986-X.

Further reading

- Gustafson, Barry (1986). From the Cradle to the Grave: a biography of Michael Joseph Savage. Auckland: Reed Methuen. ISBN 0-474-00138-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Michael Joseph Savage. |

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by George Forbes |

Prime Minister of New Zealand 1935–1940 |

Succeeded by Peter Fraser |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Harry Holland |

Leader of the Opposition 1933–1935 |

Succeeded by George Forbes |

| Preceded by George Forbes |

Minister of Foreign Affairs 1935–1940 |

Succeeded by Frank Langstone |

| Minister of Native Affairs 1935–1940 | ||

| New Zealand Parliament | ||

| Preceded by Charles Poole |

Member of Parliament for Auckland West 1908–1940 |

Succeeded by Peter Carr |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Harry Holland |

Leader of the Labour Party 1933–1940 |

Succeeded by Peter Fraser |

| Preceded by James McCombs |

Deputy-Leader of the Labour Party 1923–1933 | |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

|