Methemoglobinemia

| Methemoglobinemia | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Toxicology |

| ICD-10 | D74 |

| ICD-9-CM | 289.7 |

| DiseasesDB | 8100 |

| MedlinePlus | 000562 |

| eMedicine | med/1466 emerg/313 ped/1432 |

| MeSH | D008708 |

Methemoglobinemia (or methaemoglobinaemia) is a disorder characterized by the presence of a higher than normal level of methemoglobin (metHb, i.e., ferric [Fe3+] rather than ferrous [Fe2+] haemoglobin) in the blood. Methemoglobin is a form of hemoglobin that contains ferric [Fe3+] iron and has a decreased ability to bind oxygen. However, the ferrous iron has an increased affinity for bound oxygen.[1] The binding of oxygen to methemoglobin results in an increased affinity of oxygen to the three other heme sites (that are still ferrous) within the same tetrameric hemoglobin unit. This leads to an overall reduced ability of the red blood cell to release oxygen to tissues, with the associated oxygen–hemoglobin dissociation curve therefore shifted to the left. When methemoglobin concentration is elevated in red blood cells, tissue hypoxia can occur.

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of methemoglobinemia (methemoglobin level above 1%) include shortness of breath, cyanosis, mental status changes (~50%), headache, fatigue, exercise intolerance, dizziness and loss of hairlines.

Patients with severe methemoglobinemia (methemoglobin level above 50%) may exhibit seizures, coma and death (>70%).[2] Healthy people may not have many symptoms with methemoglobin levels below 15%. However, patients with co-morbidities such as anemia, cardiovascular disease, lung disease, sepsis, or presence of other abnormal hemoglobin species (e.g. carboxyhemoglobin, sulfhemoglobin or sickle hemoglobin) may experience moderate to severe symptoms at much lower levels (as low as 5–8%).Also known for blue skin.

Pathophysiology

Normally, methemoglobin levels are <1%, as measured by the co-oximetry test. Elevated levels of methemoglobin in the blood are caused when the mechanisms that defend against oxidative stress within the red blood cell are overwhelmed and the oxygen carrying ferrous ion (Fe2+) of the heme group of the hemoglobin molecule is oxidized to the ferric state (Fe3+). This converts hemoglobin to methemoglobin, resulting in a reduced ability to release oxygen to tissues and thereby hypoxia. This can give the blood a bluish or chocolate-brown color. Spontaneously formed methemoglobin is normally reduced (regenerating normal hemoglobin) by protective enzyme systems, e.g., NADH methemoglobin reductase (cytochrome-b5 reductase) (major pathway), NADPH methemoglobin reductase (minor pathway) and to a lesser extent the ascorbic acid and glutathione enzyme systems. Disruptions with these enzyme systems lead to methemoglobinemia.

Hypoxia occurs due to the decreased oxygen-binding capacity of methemoglobin, as well as the increased oxygen-binding affinity of other subunits in the same hemoglobin molecule, which prevents them from releasing oxygen at normal tissue oxygen levels.

Diagnosis

Arterial blood with elevated methemoglobin levels has a characteristic chocolate-brown color as compared to normal bright red oxygen-containing arterial blood.[2] If methemoglobinemia is suspected, an arterial blood gas and co-oximetry panel should be obtained.

Classification

Acquired

Methemoglobinemia may be acquired.[3] Classical drug causes of methemoglobinaemia include antibiotics (trimethoprim, sulfonamides and dapsone[4]), local anesthetics (especially articaine, benzocaine, and prilocaine[5]), and aniline dyes, metoclopramide, rasburicase, chlorates and bromates. Ingestion of compounds containing nitrates (such as the patina chemical bismuth nitrate) can also cause methemoglobinemia.

In otherwise healthy individuals, the protective enzyme systems normally present in red blood cells rapidly reduce the methemoglobin back to hemoglobin and hence maintain methemoglobin levels at less than one percent of the total hemoglobin concentration. Exposure to exogenous oxidizing drugs and their metabolites (such as benzocaine, dapsone and nitrates) may lead to up to a thousandfold increase of the methemoglobin formation rate, overwhelming the protective enzyme systems and acutely increasing methemoglobin levels.

Infants under 6 months of age have lower levels of a key methemoglobin reduction enzyme (the NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase) in their red blood cells. This results in a major risk of methemoglobinemia caused by nitrates ingested in drinking water,[6] dehydration usually caused by gastroenteritis with diarrhea, sepsis, and topical anesthetics containing benzocaine or prilocaine. Nitrates used in agricultural fertilizers may leak into the ground and may contaminate well water. The current EPA standard of 10 ppm nitrate-nitrogen for drinking water is specifically designed to protect infants.[6] Benzocaine applied to the gums or throat (as commonly used in baby teething gels, or sore throat lozenges) can cause methemoglobinemia.[7]

Congenital

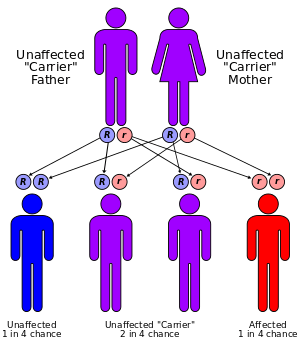

Due to a deficiency of the enzyme diaphorase I (NADH methemoglobin reductase), methemoglobin levels rise and the blood of met-Hb patients has reduced oxygen-carrying capacity. Instead of being red in color, the arterial blood of met-Hb patients is brown. This results in the skin of Caucasian patients gaining a bluish hue. Hereditary met-Hb is caused by a recessive gene. If only one parent has this gene, offspring will have normal-hued skin, but if both parents carry the gene, there is a chance the offspring will have blue-hued skin.

Another cause of congenital methemoglobinemia is seen in patients with abnormal hemoglobin variants such as hemoglobin M (HbM), or hemoglobin H (HbH), which are not amenable to reduction despite intact enzyme systems.

Methemoglobinemia can also arise in patients with pyruvate kinase deficiency due to impaired production of NADH – the essential cofactor for diaphorase I. Similarly, patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency may have impaired production of another co-factor, NADPH.

Treatment

Methemoglobinemia can be treated with supplemental oxygen and methylene blue[8] 1% solution (10 mg/ml) 1 to 2 mg/kg administered intravenously slowly over five minutes. Although the response is usually rapid, the dose may be repeated in one hour if the level of methemoglobin is still high one hour after the initial infusion.

Methylene blue restores the iron in hemoglobin to its normal (reduced) oxygen-carrying state. This is achieved by providing an artificial electron acceptor (such as methylene blue or flavin) for NADPH methemoglobin reductase (RBCs usually don't have one; the presence of methylene blue allows the enzyme to function at 5× normal levels[9]). The NADPH is generated via the hexose monophosphate shunt.

Genetically induced chronic low-level methemoglobinemia may be treated with oral methylene blue daily. Also, vitamin C can occasionally reduce cyanosis associated with chronic methemoglobinemia but has no role in treatment of acute acquired methemoglobinemia. Diaphorase II normally contributes only a small percentage of the red blood cell's reducing capacity, but can be pharmacologically activated by exogenous cofactors (such as methylene blue) to 5 times its normal level of activity.

Society and culture

The Blue Fugates

The Fugates, a family that lived in the hills of Kentucky, are the most famous example of this hereditary genetic condition. They are known as the "Blue Fugates".[10] Martin Fugate settled near Hazard, Kentucky, around 1800. His wife was a carrier of the recessive methemoglobinemia (met-H) gene, as was a nearby clan with whom the Fugates intermarried. As a result, many descendants of the Fugates were born with met-H.[11][12][13]

The Blue Men of Lurgan

The "blue men of Lurgan" were a pair of Lurgan men suffering from what was described as "familial idiopathic methaemoglobinaemia" who were treated by Dr. James Deeny in 1942. Deeny, who would later become the Chief Medical Officer of the Republic of Ireland, prescribed a course of ascorbic acid and sodium bicarbonate. In case one, by the eighth day of treatment there was a marked change in appearance, and by the twelfth day of treatment the patient's complexion was normal. In case two, the patient's complexion reached normality over a month-long duration of treatment.[14]

See also

- Argyria, another condition known for causing blue skin coloration.

- Eleven Blue Men

References

- ↑ "Methemoglobinemia". Medscape. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- 1 2 "eMedicine - Methemoglobinemia". Retrieved 2008-09-13.

- ↑ Ash-Bernal R, Wise R, Wright SM (2004). "Acquired methemoglobinemia: a retrospective series of 138 cases at 2 teaching hospitals". Medicine (Baltimore) 83 (5): 265–273. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000141096.00377.3f. PMID 15342970.

- ↑ Zosel A, Rychter K, Leikin JB (2007). "Dapsone-induced methemoglobinemia: case report and literature review". Am J Ther 14 (6): 585–587. doi:10.1097/MJT.0b013e3180a6af55. PMID 18090884.

- ↑ Adams V, Marley J, McCarroll C (2007). "Prilocaine induced methaemoglobinaemia in a medically compromised patient. Was this an inevitable consequence of the dose administered?". Br Dent J 203 (10): 585–587. doi:10.1038/bdj.2007.1045. PMID 18037845.

- 1 2 "Basic Information about Nitrate in Drinking Water". United State Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Reports of a rare, but serious and potentially fatal adverse effect with the use of over-the-counter (OTC) benzocaine gels and liquids applied to the gums or mouth". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 7 April 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ Yusim Y, Livingstone D, Sidi A (2007). "Blue dyes, blue people: the systemic effects of blue dyes when administered via different routes". J Clin Anesth 19 (4): 315–321. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2007.01.006. PMID 17572332.

- ↑ Yubisui T; Takeshita M; Yoneyama Y. Reduction of methemoglobin through flavin at the physiological concentration by NADPH-flavin reductase of human erythrocytes. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1980 Jun;87(6):1715-20. PMID 7400118

- ↑ "Blue-skinned family baffled science for 150 years". MSN. 24 February 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ Straight Dope article on the Fugates of Appalachia, an extended family of blue-skinned people

- ↑ Tri City Herald, November 7, 1974 p.32 Newspaper reports on the Blue Fugates

- ↑ Fugates of Kentucky: Skin Bluer than Lake Louise

- ↑ Deeny, James (1995). The End of an Epidemic. Dublin: A.& A.Farmar. ISBN 1-899047-06-9.

External links

- ATSDR Case Studies in Environmental Medicine: Nitrate/Nitrite Toxicity U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (public domain)