Mesocyclone

A mesocyclone is a vortex of air within a convective storm.[1] It is air that rises and rotates around a vertical axis, usually in the same direction as low pressure systems in a given hemisphere. They are most often cyclonic, that is, associated with a localized low-pressure region within a severe thunderstorm. Such thunderstorms can feature strong surface winds and severe hail. Mesocyclones often occur together with updrafts in supercells, within which tornadoes may form at the interchange with certain downdrafts.

Mesocyclones are localized, approximately 2 km (1.2 mi) to 10 km (6.2 mi) in diameter within strong thunderstorms.[1] Thunderstorms containing persistent mesocyclones are supercell thunderstorms. Mesocyclones occur on the "mesoscale", a more general term used in meteorology to denote organization on scales from a few up to hundreds of kilometers. Doppler radar is used to identify mesocyclones. A mesovortex is a similar but typically smaller and weaker rotational feature associated with squall lines.

Formation

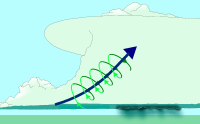

Mesocyclones form when strong changes of wind speed and/or direction with height ("wind shear") sets parts of the lower part of the atmosphere spinning in invisible tube-like rolls. The convective updraft of a thunderstorm then draw up this spinning air, tilting the rolls' orientation upward (from parallel to the ground to perpendicular) and causing the entire updraft to rotate as a vertical column.[2]

As the updraft rotates and ingests cooler moister air from the forward flank downdraft (FFD), it may form a wall cloud, a spinning layer of clouds lowered from ambient storm cloud base under the mid-level mesocyclone. The wall cloud tends to form closer to the center of the mesocyclone. As it descends, a funnel cloud may form near its center. This is the first visible stage of tornadogenesis.

|

Identification

The best way to detect and verify the presence of a mesocyclone is by Doppler weather radar. Nearby high values of opposite sign within velocity data are how they are detected.[3] Thus the word mesocyclone is associated with weather radar terminology. Mesocyclones are most often identified in the right-rear flank of supercell thunderstorms and squall lines, and may be distinguished by a hook echo rotation signature on a weather radar map. Visual cues such as a rotating wall cloud or tornado may also hint at the presence of a mesocyclone. This is why the term has entered into wider usage in connection with rotating features in severe storms.

Tornado formation

Tornado formation generally occurs in one of two ways.

In the first method, two conditions must be first satisfied.[4] One, an invisible horizontal spinning effect must be first formed upon the Earth's surface. This is usually formed by sudden changes in wind direction or speed, known as wind shear. Second, a thundercloud, or occasionally a cumulus cloud, must be present. During a thunderstorm, the updrafts presented are occasionally powerful enough to lift the horizontal spinning row of air upwards, turning it into a vertical air column. This vertical air column then becomes the basic structure for the tornado. Tornadoes that form in this way are often classified as weak tornadoes and [generally] last for less than 10 minutes.[4]

The second method of formation occurs during the occurrence of a supercell thunderstorm. This type of tornado forms by the updrafts present in the supercell thunderstorm. When winds occurring during this phenomenon increase and intensify, the force released can cause the updrafts to rotate. This rotating updraft is known as a mesocyclone.[5] For a tornado to form in this manner, a downdraft called the rear-flank downdraft enters the center of the mesocyclone from the back. Cold air, being denser than warm air is able to penetrate through the updraft. The combination of the updraft and downdraft completes the development of a tornado. Tornadoes that form in this method are often classified as violent and are capable of lasting for more than one hour.[4]

Mesoscale convective vortex

A mesoscale convective vortex (MCV), also known as a mesoscale vorticity center or Neddy eddy,[6] is a mesocyclone within an mesoscale convective system (MCS) that pulls winds into a circling pattern, or vortex, at the mid levels of the troposphere and is normally associated with anticyclonic outflow aloft. With a core only 30 to 60 miles wide and 1 to 3 miles deep, an MCV is often overlooked in standard weather maps. MCVs can persist for up to 2 days after its parent mesoscale convective system has dissipated.[6] The orphaned MCV can become the seed of the next thunderstorm outbreak. An MCV that moves into tropical waters, such as the Gulf of Mexico, can serve as the nucleus for a tropical storm or hurricane. MCVs can produce very large wind storms; sometimes winds can reach over 100 mph. The May 2009 Southern Midwest Derecho was an extreme progressive derecho and mesoscale convective vortex event that struck Southeastern Kansas, Southern Missouri, and Southwestern Illinois on May 8, 2009.

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mesocyclone diagrams. |

- 1 2 Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Mesocyclone". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ↑ University of Illinois. Vertical Wind Shear Retrieved on 2006-10-21.

- ↑ Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Mesocyclone signature". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- 1 2 3 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (September 1992). "tornadoes...Nature's Most Violent Storms". A Preparedness Guide. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- ↑ Thinkquest (October 2003). "Tornado Formation". Oracle Corporation. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- 1 2 Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies (2004-01-22). "08 July 1997 -- Mesoscale Convective Complex decays,revealing a Mesoscale Vorticity Center". University of Wisconsin-Madison. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

External links

| ||||||||||||||