Lymphadenopathy

| Lymphadenopathy | |

|---|---|

|

Neck lymphadenopathy associated with infectious mononucleosis | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| ICD-10 | I88, L04, R59.1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 289.1-289.3, 683, 785.6 |

| DiseasesDB | 22225 |

| MedlinePlus | 001301 |

| eMedicine | ped/1333 |

| MeSH | D008206 |

Lymphadenopathy or lymphadenitis refers to lymph nodes which are abnormal in size, number or consistency [1] and is often used as a synonym for swollen or enlarged lymph nodes. Common causes of lymphadenopathy are infection, autoimmune disease, or malignancy.

Inflammation as a cause of lymph node enlargement is known as lymphadenitis.[2] In practice, the distinction between lymphadenopathy and lymphadenitis is rarely made. Inflammation of the lymphatic vessels is also known as lymphangitis.[3] Infectious lymphadenitides affecting lymph nodes in the neck are often called scrofula.

The term comes from the word lymph and a combination of the Greek words αδένας, adenas ("gland") and παθεία, patheia ("act of suffering" or "disease").

Due to its peculiar high incidence, the presence of lymphadenopathy is a particularly important sign on the diagnosis of HIV or even, untreated later stages of the infection, AIDS.

Types

- Localized lymphadenopathy: due to localized spot of infection e.g., an infected spot on the scalp will cause lymph nodes in the neck on that same side to swell up

- Generalized lymphadenopathy: due to a systemic infection of the body e.g., influenza or secondary syphilis

- Persistent generalized lymphadenopathy (PGL): persisting for a long time, possibly without an apparent cause

- Dermatopathic lymphadenopathy: lymphadenopathy associated with skin disease.

Causes

Lymph node enlargement is recognized as a common sign of infectious, autoimmune, or malignant disease. Examples may include:

- Reactive: acute infection (e.g., bacterial, or viral), or chronic infections (tuberculous lymphadenitis,[4] cat-scratch disease[5]).

- The most distinctive sign of bubonic plague is extreme swelling of one or more lymph nodes that bulge out of the skin as "buboes." The buboes often become necrotic and may even rupture.[6]

- Infectious mononucleosis is an acute viral infection caused by Epstein-Barr virus and may be characterized by a marked enlargement of the cervical lymph nodes.[7]

- It is also a sign of cutaneous anthrax[8] and Human African trypanosomiasis[9]

- Toxoplasmosis, a parasitic disease, gives a generalized lymphadenopathy (Piringer-Kuchinka lymphadenopathy).[10]

- Plasma cell variant of Castleman's disease - associated with HHV-8 infection and HIV infection[11][12]

- Mesenteric lymphadenitis after viral systemic infection (particularly in the GALT in the appendix) can commonly present like appendicitis.[13][14]

Less common infectious causes of lymphadenopathy may include bacterial infections such as cat scratch disease, tularemia, brucellosis, or prevotella.

- Tumoral:

- Primary: Hodgkin lymphoma[15] and non-Hodgkin lymphoma give lymphadenopathy in all or a few lymph nodes.[10]

- Secondary: metastasis, Virchow's Node, neuroblastoma,[16] and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.[17]

- Autoimmune etiology: systemic lupus erythematosus[18] and rheumatoid arthritis may have a generalized lymphadenopathy.[10]

- Immunocompromised etiology: AIDS. Generalized lymphadenopathy is an early sign of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).[19] "Lymphadenopathy syndrome" has been used to describe the first symptomatic stage of HIV progression, preceding a diagnosis of AIDS.

- Bites from certain venomous snakes such as the pit viper[20]

- Unknown etiology: Kikuchi disease,[21] progressive transformation of germinal centers, sarcoidosis, hyaline-vascular variant of Castleman's disease, Rosai-Dorfman disease,[22] Kawasaki disease,[23] Kimura disease[24]

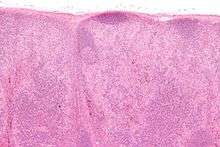

Benign (reactive) lymphadenopathy

Benign lymphadenopathy is a common biopsy finding, and may often be confused with malignant lymphoma. It may be separated into major morphologic patterns, each with its own differential diagnosis with certain types of lymphoma. Most cases of reactive follicular hyperplasia are easy to diagnose, but some cases may be confused with follicular lymphoma. There are six distinct patterns of benign lymphadenopathy:[25]

- Follicular hyperplasia: This is the most common type of reactive lymphadenopathy.[7]

- Paracortical hyperplasia/Interfollicular hyperplasia: It is seen in viral infections, skin diseases, and nonspecific reactions.

- Sinus histiocytosis: It is seen in lymph nodes draining limbs, inflammatory lesions, and malignancies.

- Nodal extensive necrosis

- Nodal granulomatous inflammation

- Nodal extensive fibrosis (Connective tissue framework)

- Nodal deposition of interstitial substance

These morphological patterns are never pure. Thus, reactive follicular hyperplasia can have a component of paracortical hyperplasia. However, this distinction is important for the differential diagnosis of the cause.

Localization

See also

References

- ↑ King, D; Ramachandra, J; Yeomanson, D (2 January 2014). "Lymphadenopathy in children: refer or reassure?". Archives of disease in childhood. Education and practice edition 99: 101–110. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2013-304443. PMID 24385291.

- ↑ "lymphadenitis" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ "lymphangitis" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Fontanilla, JM; Barnes, A; Von Reyn, CF (September 2011). "Current diagnosis and management of peripheral tuberculous lymphadenitis". Clinical Infectious Diseases 53 (6): 555–562. doi:10.1093/cid/cir454. PMID 21865192.

- ↑ Klotz, SA; Ianas, V; Elliott, SP (2011). "Cat-scratch Disease". American Family Physician 83 (2): 152–155. PMID 21243990.

- ↑ Butler, T (2009). "Plague into the 21st century". Clinical Infectious Diseases 49 (5): 736–742. doi:10.1086/604718. PMID 19606935.

- 1 2 Weiss, LM; O'Malley, D (2013). "Benign lymphadenopathies". Modern Pathology 26 (Supplement 1): S88–S96. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2012.176. PMID 23281438.

- ↑ Sweeney, DA; Hicks, CW; Cui, X; Li, Y; Eichacker, PQ (December 2011). "Anthrax infection". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 184 (12): 1333–1341. doi:10.1164/rccm.201102-0209CI. PMC 3361358. PMID 21852539.

- ↑ Kennedy, PG (February 2013). "Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness)". Lancet Neurology 12 (2): 186–194. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70296-X. PMID 23260189.

- 1 2 3 Status and anamnesis, Anders Albinsson. Page 12

- ↑ Kim, TU; Kim, S; Lee, JW; Lee, NK; Jeon, UB; Ha, HG; Shin, DH (September–October 2012). "Plasma cell type of Castleman's disease involving renal parenchyma and sinus with cardiac tamponade: case report and literature review". Korean Journal of Radiology 13 (5): 658–663. doi:10.3348/kjr.2012.13.5.658. PMC 3435867. PMID 22977337.

- ↑ Zhang, H; Wang, R; Wang, H; Xu, Y; Chen, J (June 2012). "Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in Castleman's disease: a systematic review of the literature and 2 case reports". Internal Medicine (Tokyo, Japan) 51 (12): 1537–1542. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.51.6298. PMID 22728487.

- ↑ Bratucu, E; Lazar, A; Marincaş, M; Daha, C; Zurac, S (March–April 2013). "Aseptic mesenteric lymph node abscesses. In search of an answer. A new entity?" (PDF). Chirurgia (Bucarest, Romania: 1990) 108 (2): 152–160. PMID 23618562.

- ↑ Leung, A; Sigalet, DL (June 2003). "Acute Abdominal Pain in Children". American Family Physician 67 (11): 2321–2327.

- ↑ Glass, C (September 2008). "Role of the Primary Care Physician in Hodgkin Lymphoma". American Family Physician 78 (5): 615–622. PMID 18788239.

- ↑ Colon, NC; Chung, DH (2011). "Neuroblastoma". Advances in Pediatrics 58 (1): 297–311. doi:10.1016/j.yapd.2011.03.011. PMC 3668791. PMID 21736987.

- ↑ Sagatys, EM; Zhang, L (January 2011). "Clinical and laboratory prognostic indicators in chronic lymphocytic leukemia". Cancer Control 19 (1): 18–25. PMID 22143059.

- ↑ Melikoglu, MA; Melikoglu, M (October–December 2008). "The clinical importance of lymphadenopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus" (PDF). Acta Reumatologia Portuguesa 33 (4): 402–406. PMID 19107085.

- ↑ Lederman, MM; Margolis, L (June 2008). "The lymph node in HIV pathogenesis". Seminars in Immunology 20 (3): 187–195. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2008.06.001. PMC 2577760. PMID 18620868.

- ↑ Quan, D (October 2012). "North American poisonous bites and stings". Critical Care Clinics 28 (4): 633–659. doi:10.1016/j.ccc.2012.07.010. PMID 22998994.

- ↑ Komagamine, T; Nagashima, T; Kojima, M; Kokubun, N; Nakamura, T; Hashimoto, K; Kimoto, K; Hirata, K (September 2012). "Recurrent aseptic meningitis in association with Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: case report and literature review". BMC Neurology 12: 187–195. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-12-112. PMC 3570427. PMID 23020225.

- ↑ Noguchi, S; Yatera, K; Shimajiri, S; Inoue, N; Nagata, S; Nishida, C; Kawanami, T; Ishimoto, H; Sasaguri, Y; Mukae, H (2012). "Intrathoracic Rosai-Dorfman disease with spontaneous remission: a clinical report and a review of the literature". The Tokohu Journal of Experimental Medicine 227 (3): 231–235. doi:10.1620/tjem.227.231. PMID 22789970.

- ↑ Weiss, PF (April 2012). "Pediatric vasculitis". Pediatric Clinics of North America 59 (2): 407–423. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2012.03.013. PMC 3348547. PMID 22560577.

- ↑ Koh, H; Kamiishi, N; Chiyotani, A; Takahashi, H; Sudo, A; Masuda, Y; Shinden, S; Tajima, A; Kimura, Y; Kimura, T (April 2012). "Eosinophilic lung disease complicated by Kimura's disease: a case report and literature review". Internal Medicine (Tokyo, Japan) 51 (22): 3163–3167. PMID 23154725.

- ↑ Weiss, L. M.; O'Malley, D (2013). "Benign lymphadenopathies". Modern Pathology. 26 Suppl 1: S88–96. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2012.176. PMID 23281438.

External links

- HPC:13820 on humpath.com (Digital slides)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||