Meromorphic function

In the mathematical field of complex analysis, a meromorphic function on an open subset D of the complex plane is a function that is holomorphic on all D except a set of isolated points (the poles of the function), at each of which the function must have a Laurent series. This terminology comes from the Ancient Greek meros (μέρος), meaning part, as opposed to holos (ὅλος), meaning whole.

Every meromorphic function on D can be expressed as the ratio between two holomorphic functions (with the denominator not constant 0) defined on D: any pole must coincide with a zero of the denominator.

Intuitively, a meromorphic function is a ratio of two well-behaved (holomorphic) functions. Such a function will still be well-behaved, except possibly at the points where the denominator of the fraction is zero. If the denominator has a zero at z and the numerator does not, then the value of the function will be infinite; if both parts have a zero at z, then one must compare the multiplicities of these zeros.

From an algebraic point of view, if D is connected, then the set of meromorphic functions is the field of fractions of the integral domain of the set of holomorphic functions. This is analogous to the relationship between the rational numbers and the integers.

History

In the 1930s, in group theory, a meromorphic function (or meromorph) was a function from a group G into itself that preserved the product on the group. The image of this function was called an automorphism of G.[1] Similarly, a homomorphic function (or homomorph) was a function between groups that preserved the product, while a homomorphism was the image of a homomorph. This terminology is now obsolete. The term endomorphism is now used for the function itself, with no special name given to the image of the function. The term meromorph is no longer used in group theory.

Properties

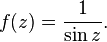

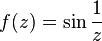

Since the poles of a meromorphic function are isolated, there are at most countably many. The set of poles can be infinite, as exemplified by the function

By using analytic continuation to eliminate removable singularities, meromorphic functions can be added, subtracted, multiplied, and the quotient  can be formed unless

can be formed unless  on a connected component of D. Thus, if D is connected, the meromorphic functions form a field, in fact a field extension of the complex numbers.

on a connected component of D. Thus, if D is connected, the meromorphic functions form a field, in fact a field extension of the complex numbers.

Higher dimensions

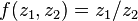

In several complex variables, a meromorphic function is defined to be locally a quotient of two holomorphic functions. For example,  is a meromorphic function on the two-dimensional complex affine space. Here it is no longer true that every meromorphic function can be regarded as holomorphic function with values in the Riemann sphere: There is a set of "indeterminacy" of codimension two (in the given example this set consists of the origin

is a meromorphic function on the two-dimensional complex affine space. Here it is no longer true that every meromorphic function can be regarded as holomorphic function with values in the Riemann sphere: There is a set of "indeterminacy" of codimension two (in the given example this set consists of the origin  ).

).

Unlike in dimension one, in higher dimensions there do exist complex manifolds on which there are no non-constant meromorphic functions, for example, most complex tori.

Examples

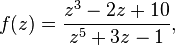

- All rational functions such as

- are meromorphic on the whole complex plane.

- The functions

- as well as the gamma function and the Riemann zeta function are meromorphic on the whole complex plane.

- The function

- is defined in the whole complex plane except for the origin, 0. However, 0 is not a pole of this function, rather an essential singularity. Thus, this function is not meromorphic in the whole complex plane. However, it is meromorphic (even holomorphic) on

.

.

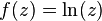

- The complex logarithm function

- is not meromorphic on the whole complex plane, as it cannot be defined on the whole complex plane while only excluding an isolated set of points.

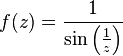

- The function

- is not meromorphic in the whole plane, since the point

is an accumulation point of poles and is thus not an isolated singularity. The function

is an accumulation point of poles and is thus not an isolated singularity. The function

- is not meromorphic either, as it has an essential singularity at 0.

On Riemann surfaces

On a Riemann surface, every point admits an open neighborhood which is homeomorphic to an open subset of the complex plane. Thereby the notion of a meromorphic function can be defined for every Riemann surface.

When D is the entire Riemann sphere, the field of meromorphic functions is simply the field of rational functions in one variable over the complex field, since one can prove that any meromorphic function on the sphere is rational. (This is a special case of the so-called GAGA principle.)

For every Riemann surface, a meromorphic function is the same as a holomorphic function that maps to the Riemann sphere and which is not constant ∞. The poles correspond to those complex numbers which are mapped to ∞.

On a non-compact Riemann surface, every meromorphic function can be realized as a quotient of two (globally defined) holomorphic functions. In contrast, on a compact Riemann surface, every holomorphic function is constant, while there always exist non-constant meromorphic functions.

Meromorphic functions on an elliptic curve are also known as elliptic functions.

By extension

Sometimes the expression "meromorphic at a" implies holomorphic in a punctured neighborhood of a.

References

- ↑ Zassenhaus pp. 29, 41

- Lang, Serge (1999), Complex analysis (4th ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-98592-3

- Zassenhaus, Hans (1937), Lehrbuch der Gruppentheorie (1st ed.), Leipzig, Berlin: Verlag und Druck von B.G.Teubner

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Meromorphic function", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

|